When I was invited into collector Rick Synchef’s home several months ago, I was drawn by the promise of signed rock posters from the San Francisco music scene, as well as first-edition copies of Beat poetry by such luminaries as Allen Ginsberg and Lawrence Ferlinghetti. But it was Synchef’s collection of flyers, pamphlets, and other ephemera, distributed by groups such as the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) and the Yippies, that made the greatest impression on me.

“I was tear-gassed or pepper-sprayed about 30 times.”

At the time, Occupy Wall Street protestors had made the disparity of wealth in the United States a presidential campaign issue, while protestors in Oakland, California, shut down that city’s port, albeit briefly. As I looked at Synchef’s collection (only a tiny fraction of which is shown here), carefully removed from flat files stored beneath his bed and archival boxes packed into closets, it seemed as if the blueprints for the Occupy movement were being laid out before me.

Synchef began collecting political paper while still an undergraduate at the University of Wisconsin in Madison. “Madison was often referred to as the Berkeley of the Midwest,” Synchef recalls. “I thought I was politically aware, but Madison was an eye-opening experience.”

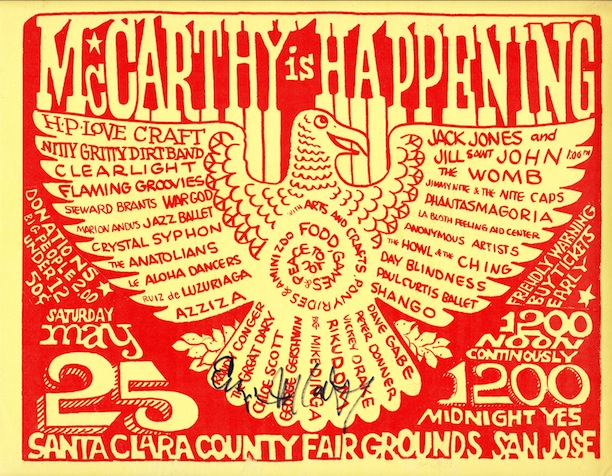

Top: A Eugene McCarthy for President event, 1968, signed by the candidate. Above, left: A Yippie flyer promoting events during the Democratic National Convention, 1968. Above right: The cover of an SDS booklet timed for the trial of Yippie and other leaders arrested at the August event.

Although the lightning-rod issue for student activists in the late ’60s was opposition to the war in Vietnam, Synchef remembers the motivation of the movement as being more far-reaching. “It was about human rights in general,” he says, “about trying to make people’s lives better and more meaningful.” It was also about challenging the power structure, particularly the incestuous relationship between government agencies and the corporations that benefited from their policies.

Sound familiar?

By 1970, demonstrations at Madison and many other universities were nearly constant, especially after May 4, when National Guard officers shot and killed four students at Kent State University in Ohio. “I estimate I was tear-gassed or pepper-sprayed about 30 times,” Synchef says of his four years at Madison. “Not me personally, but I’d be in situations where the cops would just fog the area with pepper spray. They’d drive by in vans and pepper-spray masses of people.”

These days, such events become instant Internet memes.

This 1969 flyer for an event in San Francisco advertised one of several peace marches around the country that day.

Against this backdrop, Synchef began collecting leaflets and other pieces of political ephemera. “I just started saving things, like handbills that had been stuck to telephone poles, or flyers used to promote events and speakers on campus. I knew we were going through a really significant and unique period in American history. I had a gut feeling that it might never happen again. This was before e-mails, before fax machines. Those pieces of paper were how people found out about events; they were never intended to be permanent. I thought, and I still think, that these things needed to be preserved. They’re a really important part of American history.”

Later, after graduating from law school at Northwestern University in Chicago, Synchef added to his collection by purchasing, “an occasional poster here and there,” as he puts it. “But what really spurred me on,” he says, “is that in the late 1980s, I happened upon a catalog of bohemia and ’60s literature—first editions and signed works. I call them cheap but meaningful pamphlets, but they were treated with respect in a catalog ordinarily reserved for rare books and manuscripts. Someone was making a real attempt to categorize and define these things in a logical and coherent way.”

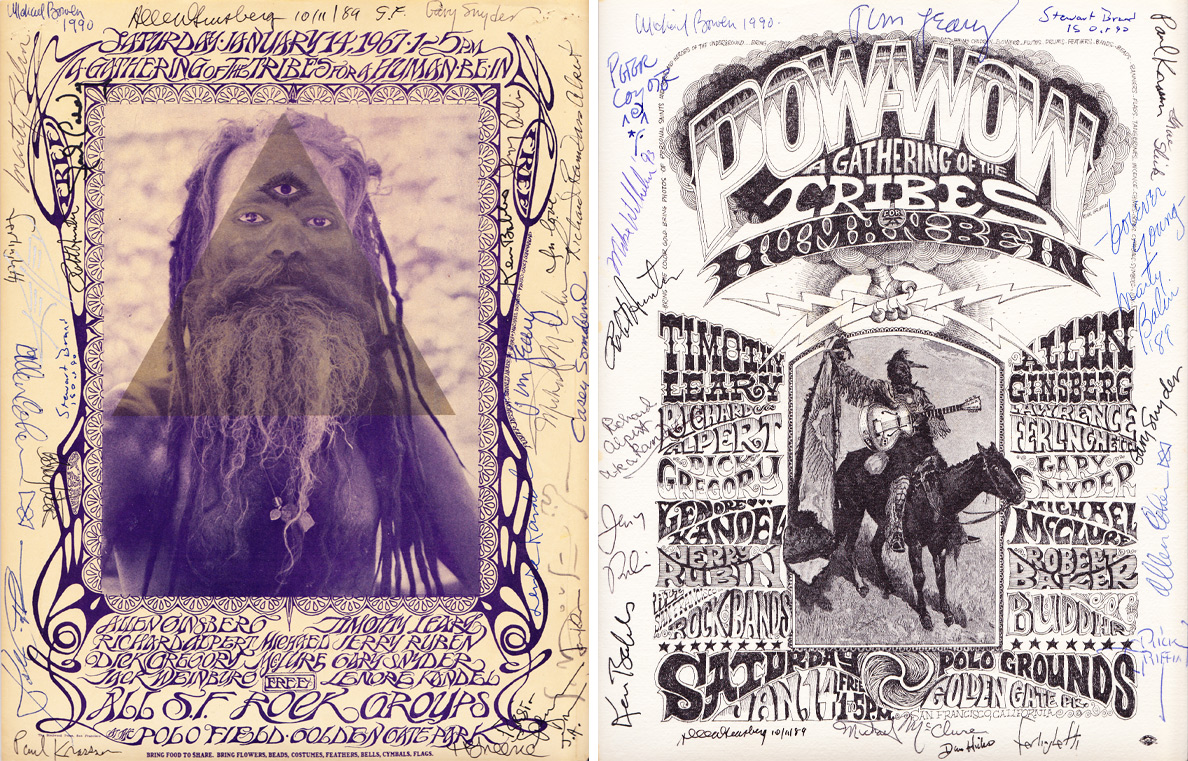

Two posters were produced for the Human Be-In in Golden Gate Park. The one on the left was designed by rock-poster artist Stanley Mouse and “Oracle” art director Michael Bowen. The one on the right is by rock-poster artist Rick Griffin. Synchef’s copies have been signed by many of the day’s participants, including Timothy Leary and Allen Ginsberg.

Synchef bought a few pieces from the catalog, “and then it became obsessive,” he says. “I actually ran a couple advertisements in paper-collector magazines, and learned how to preserve things in Mylar and archival cardboard boxes.”

Before long, he had collected ephemera produced by numerous branches of the counterculture, from underground newspapers such as “The East Village Other,” which served residents of that New York City neighborhood, to handbills promoting the famous Human Be-In, which was held on January 14, 1967, in San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park. Some events were tied to political causes, while others seemed more about the human spirit. “It’s all a continuum,” Synchef says. “The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee [SNCC] helped the summer freedom riders that went to the South in the early ’60s to register black voters. It’s really hard to draw boundaries between all the different types of, shall we say, human-potential movements.”

One of the earliest student-activism documents in Synchef’s collection is a copy of the Port Huron Statement. “In 1962, approximately 50 student leaders met from around the country in Port Huron, Michigan, to put together a declaration of principles, if you will, advocating for participatory democracy. Primarily written by Tom Hayden, the Port Huron Statement was a seminal document in student activism.”

Some of its tips, specifically the one to “make debate and controversy,” sound like tenets of Occupy Wall Street. “I went to a few Occupy events,” adds Synchef, “and I felt surprisingly like I did in the old days. People were really sincere. They were really trying to make a difference.”

Like many social observers, Synchef sees numerous parallels between the 1960s and today. “In the ’60s, the country was incredibly divided. You were either a hawk or a dove; there was no middle ground. Same is true today.” And just as certain wings of the Occupy movement appear more radical to outsiders than others, the various groups within the student-activism movement of the 1960s had their different approaches, too. “There were the Students for a Democratic Society,” says Synchef, “as well as the Yippies started by Paul Krassner, Abbie Hoffman, and Jerry Rubin. There were also the Black Panthers and the Weather Underground.”

Written in 1962 by Tom Hayden and others, The Port Huron Statement (click to enlarge the front and back covers) became a blueprint for political activism in the 1960s.

Each group had its own particular agenda, and today, each is remembered differently in the popular imagination. “I don’t want to say the Yippies were not as serious as the SDS,” says Synchef. “They were absolutely as serious, but they engaged in a kind of demonstration that was a little more like street theater. They did things to get attention, like when Abbie Hoffman and others threw dollar bills on the trading floor at the New York Stock Exchange, just to create the spectacle of everybody scrambling for the money. They staged events that were good at garnering publicity.”

Other groups such as the Weather Underground took more drastic measures to make their case. “They engaged in property damage to bring attention to what was going on in the country,” he says. “I certainly can’t speak for them, and I hate to try to say what they did in one sentence, but basically they were unsatisfied with the pace of progress. Their goal, I think, was the same as other groups—to achieve a more-just society and end the war—but they wanted to get results more quickly.”

At the other end of the spectrum were organizations like Clergy and Laymen Concerned About Vietnam, and Mothers Against the War. “Everyone helped in his or her own way,” Synchef continues. “People did what felt comfortable.”

Just as these groups in the 1960s and early ’70s drew attention to the war in Vietnam, Occupy Wall Street has had a major impact on today’s public discourse. “If one year ago you had told me that wealth inequality would be one of the focuses of the presidential campaign, I wouldn’t have believed it,” Synchef says. “Now, the disparity between the haves and the have-nots, along with the disappearing middle-class dream, is one of the main discussion points in this election.”

In 2011, the band Moonalice commissioned a number of artists, including Winston Smith, to produce posters supporting the Occupy movement.

Equally surprising, perhaps, is the notion that old pieces of paper associated with groups that often espoused anti-materialism views would become a genre of collectibles. Indeed, Synchef’s collection contains hundreds of signed items, often bearing the scrawls of numerous people involved with a particular event. But for Synchef, those signatures are less about collecting autographs in the celebrity sense than they are a desire to connect the documents in his collection with the people whose actions inspired them.

“In order to get those signatures,” he says, “I got to meet some absolutely fascinating people who were involved in a significant period in American history. The signatures link people to the movements they were involved in, like Paul Krassner to the Yippies or Ken Kesey to the Merry Pranksters. Whether it adds value to a piece of paper, I can’t say.”

(All images except the last one courtesy Richard Synchef, who can be reached at rsynchef01@yahoo.com; Occupy poster courtesy Winston Smith and Moonalice)

Occupy Boardwalk: How Games Got Greedy

Occupy Boardwalk: How Games Got Greedy

Extraordinary Collection of Counterculture Literature Up for Auction

Extraordinary Collection of Counterculture Literature Up for Auction Occupy Boardwalk: How Games Got Greedy

Occupy Boardwalk: How Games Got Greedy The High Price of a Degree in LSD

The High Price of a Degree in LSD Protest MovementsThe American Revolution began as an act of protest, so it follows that the …

Protest MovementsThe American Revolution began as an act of protest, so it follows that the … Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Viewing the documentary “MC5: A True Testimonial” should be required.

It is still not released AFAIK, but can be found floating on the web.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/MC5:_A_True_Testimonial

The Penn State libraries recently became the recipients of a large collection of protest posters collected by Tom Benson, a faculty member here. The collection has been digitized and can be found here:

http://collection1.libraries.psu.edu/cdm4/browse.php?CISOROOT=%2Fbenson

I enjoyed seeing the Oracle Magazine cover. I was at the Human Be-In and made a short 8 mm film of it. It has Janis Joplin with Big Brother and the Holding Company, Country Joe and the Fish, Timothy Leary, Alan Ginsberg read Howl, Lenore Cantrell reading one of her poems, Hell’s Angels guarding the sound truck, Ken Kesey’s bus and others that were there. I really wish there had been camcorderd at the time for capturing a better feeling for the moment. An instructor of a local community college had a friend make a copy of my film and made one for me. He was going to use it in one of his media classes. I was going to be there to answer any questions and give a “color description” of what was going on around me.

Bob Ramsdell, Albany, OR

The posters collected by Tom Benson are now published in Benson, Posters for Peace: Visual Rhetoric and Civic Action (Penn State University Press). The book was named an Outstanding Academic Title for 2015 by CHOICE.