When George Jakob Hunzinger patented his first piece of furniture in December of 1860, the United States was on the brink of a devastating Civil War. Amid the growing pressures of industrialization, the country was split between those in favor of an old-fashioned business model—dependent on slavery—and those betting on a more diversified, innovative economy. At the time, the American way of life as we know it today was hardly recognizable: Gas-powered automobiles hadn’t made their debut; electric lighting was decades away; skyscrapers did not yet exist. Yet from Hunzinger’s vantage point as a successful immigrant in New York City, possibly the most forward-thinking place on Earth, he imagined a future where humans lived among machines, and even the most humble pieces of furniture would be mechanically enhanced.

“No one else was doing this. They didn’t have a name for it yet.”

Beginning with his first patent for an extendable table whose leaves were hidden underneath when not in use, Hunzinger knew the seamless integration of technology and furniture could be a selling point. Though the Industrial Revolution had already transformed American production, the final decades of the 19th century would thrust the country into modernity, with Hunzinger’s inventions helping to pave the way.

“It’s really in the 1870s when our modern world starts to take shape, and we start to recognize the United States that we are today,” explains Barry R. Harwood, a curator of decorative arts at the Brooklyn Museum. “It’s a very pivotal, interesting moment, and Hunzinger is the foremost practitioner of this proto-modern design.” Harwood organized the exhibition and authored the catalog for the museum’s 1997 show The Furniture of George Hunzinger: Invention and Innovation in 19th-Century America, which helped ignite scholarly interest in a designer who already had a strong following among dealers and collectors.

Top: A proto-modern Hunzinger chair design, circa 1876, with wood turned to resemble bamboo. Via 1stDibs. Above left, this chair’s simple frame is partly obscured by lush period upholstery. Via the Brooklyn Museum. Right, a folding rocking chair featuring original fabric, circa 1870, and Hunzinger’s metal rails patented in 1878 (model shown below). Via the Brooklyn Museum.

Born in 1835 to a cabinetmaking family in Tuttlingen, Germany, George Hunzinger began apprenticing with his father when he was 14 and immigrated to Brooklyn, New York, around age 20. After Hunzinger arrived in New York, he worked for Auguste Pottier, a cabinetmaker of French origin, and by 1860, Hunzinger’s name was appearing independently in a Brooklyn business directory.

“Pottier was an upper-end cabinetmaker, who eventually joined up with another fellow by the name of Stymus,” Harwood explains. “Pottier & Stymus was a decorating and furniture-making firm with elite clients. They were dealing with the first robber barons.” And yet, beginning with Hunzinger’s first patented design in 1860, his products were aimed at a very different clientele than his employer.

“Hunzinger’s furniture was not consumed by the super rich, but rather by the upper middle class,” Harwood says. “His first patent was for a dining table that ingeniously incorporates the leaves to expand the table underneath: As you pull the table apart, the leaves pop up, which is pretty clever—rather than requiring you to store the leaves separately in the closet.” The table’s crank mechanism also allowed one to raise and lower the additional leaves without the help of others.

Left, an 1874 advertisement shows two Hunzinger designs patented in the 1860s. Via the Thomas J. Watson Library, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Right, the model for Hunzinger’s 1878 patent application displays a chair frame strengthened with strips of metal. Via the Brooklyn Museum.

In the 1860s, Hunzinger launched his own business, focusing on urban middle-class buyers who wanted novel, fashionable, and versatile items to decorate their homes. Most of Hunzinger’s pieces fell squarely into the emerging field of “patent furniture,” which adopted mechanical improvements to make adjustable, multi-purpose furniture for saving space and improving comfort. “By 1861, he started patenting folding chairs, which became a sort of obsession,” Harwood says. Much like today, convertible furniture—including folding chairs, sofa beds, and card tables—was very appealing to urban residents with limited space.

A Hunzinger patent from 1861 shows why his work was popular with apartment dwellers. It described a folding chair based on the common X-frame shape along with a small attached writing desk. Like this model, many of Hunzinger’s designs were known as “fancy chairs,” or what we’d call accent chairs or conversation pieces today. “In the early 19th century, it usually referred to chairs that had a great deal of hand-painted polychromatic decoration on them,” Harwood says. “For the 19th-century consumer, it meant a singular, unusual chair that you had in the parlor.”

This armchair’s original overstuffed cushion and fringed back panel overpower the whimsical geometric shapes of its turned wood members, circa 1869. Via the Brooklyn Museum.

Judging from existing examples of Hunzinger’s designs, his 1866 patent for a large reclining chair seems to be his first breakout success. “From that point on,” Harwood explains, “we start to see illustrated advertisements in newspapers for these chairs, so it’s an indication that just 10 years after he arrived, Hunzinger was doing good business.”

In addition to his technical virtuosity, Hunzinger employed clever marketing tactics, which included providing a variety of finishes and upholsteries for each item, thus allowing shoppers to customize their purchases. “In the 1870s, this notion of consumer choice was just beginning to take shape,” Harwood says. “Hunzinger would offer the same chair with different stains, ranging from a very light blonde to ebonized wood, and different styles of upholstery, from simple cotton reps—a kind of corduroy—to fancy silk velvets. He even started to gild some of the chairs in the mid-1870s, which indicates his shop was pretty successful because that required a trained gilder and a dust-free space in the factory.” The same item could thus be purchased at varying price points, appealing to different income levels within the middle- to upper-middle-class market. “We take that for granted, but in the 1870s, this kind of marketing was new,” Harwood adds.

Left, an 1869 Hunzinger chair of ebonized wood features overt ornamentation popular at the time, including the center crest and hoof feet (original upholstery was purple damask). Via the Brooklyn Museum. Right, a more streamlined Hunzinger chair, circa 1885, features original gilded wood with updated upholstery. Via the Brooklyn Museum.

To speed production and cut costs, Hunzinger also utilized modular parts that could be applied to several different items of furniture. For example, in the mid-1870s, Hunzinger designed a settee, an armchair, and a side chair with identical motifs on each. “The same legs were used for all of them,” Harwood explains. “The settee has curving arms at either end, so he used the same curving arms on the single armchair. The chairs had different-sized backs and seat frames, but the arms and legs were all the same.”

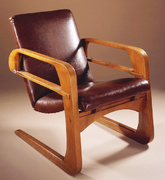

This 1890s Hunzinger chair came with a removable leather back panel, which partially hid the frame’s simple geometry. Via the Brooklyn Museum.

But perhaps most significantly, Hunzinger’s creations eschewed the excessively decorative styles popular among most furniture producers at the time. “Hunzinger was one of the first furniture makers in the United States for whom the machine, the means of production, provided the aesthetic inspiration for design,” Harwood wrote in his catalog for The Furniture of George Hunzinger. “The regularized, crisply turned members of Hunzinger’s spare furniture resemble the very machines that produced them.”

Almost half a century before the design movement known as Modernism, Hunzinger applied similar tenets to his furniture—focusing on function rather than ornamentation and utilizing geometric forms inspired by the simple lines of machinery. To be sure, other furniture companies relied on current technology to produce their pieces, but they typically did so in the service of extraneous ornamentation demanded by popular Victorian styles like Eastlake or Rococo Revival.

“In the early part of the 19th century,” Harwood says, “furniture makers and designers were trying to devise a machine that could carve flowers, because that was the most time-consuming part of furniture-making, requiring the greatest skill. But a machine doesn’t really want to do that.” Different carving machines were developed, but they could never could match what a skilled craftsperson could do by hand.

In contrast, Hunzinger allowed the assets of existing machinery to inform his designs, rather than adapting tools to imitate popular styles. “Hunzinger’s favorite tool was the lathe,” Harwood continues, “which he used to make furniture with interesting turnings. He responded to the precision of its sharp indentations to create a certain rhythm on a piece furniture. Hunzinger let the lathe do what it does best, and that’s the beginning of the machine aesthetic—not fighting against the machine, but working with it.”

As an artist, Hunzinger had a singular vision that was executed exactly as he wished. “Hunzinger’s obituary tells us that he personally designed everything he manufactured,” Harwood says. “I think given that fact, he must have been a bit of a control freak. But the obituary also included this incredibly intriguing line that says, ‘The furniture was distinctive and looked like no one else’s.’ They didn’t have the words to say that it looked ‘modern’ or ‘progressive,’ but they knew that he was doing something new and atypical, something no one else was doing.”

In other words, consumers who bought Hunzinger’s furniture appreciated the forward-looking aesthetic, a rarity in an era when the most popular styles were revivals or amalgamations of historic trends. “Appreciating newness is a very modern sensibility, to value newness or novelty in terms of invention,” Harwood adds. Hunzinger’s designs weren’t intended for the generic or unsophisticated home—they were intended to stand out for their innovative forms. “He was one of the first people to market those notions.”

That said, Hunzinger wasn’t immune to fads, and he often incorporated elements of concurrent design trends into his work. As Harwood explains in his book, “Hunzinger was willing to offer his inventive chair designs in the aesthetically pared-down version of his original conception or cloaked in a more accessible, popular, and conventional historical revivalism.” Today, the most striking Hunzinger products tend to be those that were originally the cheapest—the least-embellished versions.

Sometimes his work is referred to as “Neo-Grec,” as certain designs were informed by drawings of classical Greek and Roman furniture. “Many of Hunzinger’s chairs have a sense of historicism about them,” Harwood explains, “but they look ancient. It’s a style that became popular in Paris during the time of Napoleon III, so it’s a very sophisticated allusion to Neoclassical forms. Other pieces have this regularized turning that’s clearly an abstraction of bamboo, just as Japonism was becoming popular, but he never stooped to depicting geisha girls holding umbrellas or samurai swords. So while he was highly inventive and original, he was still a man of his own time.”

Left, an armchair, circa 1876, includes turned conical details inspired by ancient furniture combined with a seat and back of Hunzinger’s patented fabric-wrapped steel wires. Via the Brooklyn Museum. Right, a chair with a stationary-rocker base and Hunzinger’s distinctive “Lollipop” style back, circa 1870. Via Leland Little Auctions.

However, these details were secondary to his vision of housewares with streamlined, utilitarian forms. “Some examples of early 19th-century Neoclassical furniture had very straight, simple lines that appeal to today’s modern viewer,” Harwood says, “but they always terminated in a carved lion’s foot or were embellished with gilt-bronze plaques of gods and goddesses. Most of Hunzinger’s furniture had absolutely no naturalistic decoration on it at all, just relying on geometry and what the machine could produce, which gives it a very hard-edged, crisp aspect.”

Harwood points out that America’s cultural values, along with its booming economy, were well-suited to Hunzinger’s unique style. “I’m not so sure how successful he would’ve been with these designs back in the Old World,” Harwood says. “What was so extraordinary about the United States was how the market kept getting bigger and bigger as more immigrants arrived, became prosperous, entered the middle class, and bought what the factories were making.” Not surprisingly, Hunzinger’s most successful design was a quintessentially American form—a stationary rocking chair or “platform rocker,” which was patented in 1882 but stayed in production long after his death. “That’s the chair that, in relative terms, made him very successful financially,” Harwood says. “His wasn’t the only patented platform rocker, but again, because of limitations in household space, Americans became great fans of the form.”

A striking settee incorporating Hunzinger’s wire-mesh patent, circa 1876-1885. Via the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Despite the chair’s popularity, it’s likely many buyers never knew Hunzinger’s name due to the furniture distribution model: Hunzinger had a factory and showroom in New York City, but most of his products were sold through wholesalers in other cities. For consumers, the idea that these products were patented—implying innovation and novelty—was typically more important than a brand or designer, so they were generally advertised without the maker’s name.

Regardless, Hunzinger’s biggest sellers weren’t necessarily his most aesthetically impressive; designs incorporating his wire-mesh panels appear much more avant-garde. “Hunzinger’s 1876 patent for the fabric-covered, woven-wire seats and back is pretty astounding from our modern perspective,” Harwood says, “He was offering a complete alternative to the big, fancy upholstered seats of most 19th-century furniture. Instead, Hunzinger’s were functional and open and airy, literally, and have a very contemporary sensibility. I think this was his own personal reinterpretation of that traditional rattan caning that had been known for centuries, as well as the great bentwood companies in Austria, like Thonet. ”

By the time of his death in 1898, Hunzinger had secured 21 patents, more than any of his competitors. Though his heirs continued to produce some of his unique designs alongside more conventional furniture, they lacked Hunzinger’s creative vision, and the family closed the business in 1920. Today, Hunzinger’s name isn’t well known outside of antiques and design circles, despite the fact his furniture was so far ahead of the curve. “He was a genius and a visionary,” Harwood emphasizes, “and as his obituary said, no one else was doing this. They didn’t have a name for it yet.”

Kem Weber: The Mid-Century Modern Designer Who Paved the Way for IKEA

Kem Weber: The Mid-Century Modern Designer Who Paved the Way for IKEA

That Old-Time Hucksterism: The Oddest Doohickeys of Industrial-Age Entrepreneurs

That Old-Time Hucksterism: The Oddest Doohickeys of Industrial-Age Entrepreneurs Kem Weber: The Mid-Century Modern Designer Who Paved the Way for IKEA

Kem Weber: The Mid-Century Modern Designer Who Paved the Way for IKEA Dissecting the Dream of the 1890s: My Skype Date With Those Curious Neo-Victorians

Dissecting the Dream of the 1890s: My Skype Date With Those Curious Neo-Victorians Victorian FurnitureAntique Victorian furniture refers to pieces made during the reign of Queen…

Victorian FurnitureAntique Victorian furniture refers to pieces made during the reign of Queen… ChairsNo piece of antique or vintage furniture conveys as much personality and sa…

ChairsNo piece of antique or vintage furniture conveys as much personality and sa… Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

How can I send u a picture? Rocking chair

Hi Jim,

Thank you for your comment on our article. You can share your item on our Show & Tell forum for other collectors to enjoy.

Here’s how to get started.

Best of luck

CW

The concept of Furniture of the Future as envisioned by a Victorian New York designer is incredibly intriguing! It’s fascinating to consider how designers from that era, known for their ornate and intricate styles, might have imagined future innovations. The blend of Victorian craftsmanship with futuristic ideas must have created a unique vision of what furniture could be.