In the United States, Easter folklore revolves around a giant bunny bringing kids treat-filled Easter baskets, which they then use to hunt for colored eggs. In Sweden and some parts of Finland, painted eggs are common, but a traditional Easter also involves children dressing up like witches and going door-to-door asking for treats—much like American kids do on Halloween. On postcards and other vintage Easter ephemera, we have fuzzy chicks and cuddly rabbits, while the Swedes have headscarf-sporting witches transporting cats and copper coffee pots on their brooms. What happened in Northern Europe to cause mischief-making and the spooks of Halloween to join in the celebration about the rebirth of spring and the resurrection of Jesus Christ?

At the Witches’ Sabbath, the Devil wore “a gray Coat, and red and blue Stockings: He had a red Beard, a high-crown’d Hat, … and long Garters.”

In the Middle Ages, Swedes genuinely feared witches. That’s because rituals to celebrate the vernal equinox, which were once widely accepted, were demonized by priests when the Catholic Church came to dominate Sweden in the 12th century. As Alan Petrulis explains on MetroPostcard Blog, Easter time—the dark period between Christ’s death on Good Friday and resurrection on Easter Sunday—was considered particularly vulnerable to evil. Supposedly, witches would come out of hiding and fly stolen brooms or livestock on Maundy Thursday (Holy Thursday), landing on rooftops and causing all sorts of trouble for the villagers. Good Christians would hide their brooms and rakes, and paint crosses on their beasts of burden to prevent witches from hightailing off with them.

Devout Christians in Sweden and the United States have long considered Easter Sunday a time to attend services and seriously reflect on their beliefs about Jesus’ sacrifice. But people in both countries have folksy Easter traditions that derive from pre-Christian Pagan rites—the hare and baskets full of eggs came from the worship of an ancient German goddess known as Ēostre. Similarly, the idea of witches riding brooms or beasts originated with beliefs about an early Norse fertility goddess, Freyja, who was thought to ride a chariot pulled by giant cats or fly on a distaff. Often, the medieval European women who did practice witchcraft were devotees of Freyja, also known as Freya.

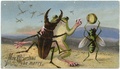

Top: An Easter Witch hurtles toward a lake as a fisherman looks on in a mid-20th century postcard by Lars “Lasse” Carlsson. Above: Edwardian-Era Easter Witches ride a ram and a large house cat on this Glad Påsk postcard. (Via On Faith)

According to Megan Garber at The Atlantic, in medieval times, rebellious European women learned how to mix substances like ergot, deadly nightshade, henbane, mandrake, and jimsonweed to make a powerful hallucinogen. They found this “witch’s brew” was best absorbed through particular membranes of the body. So they applied the mix to the end of a broomstick, inserted it into their armpits or their—ahem—nether regions, and “flew.” Eventually, the standard image of a witch became a woman literally flying on a broomstick, accompanied by a wicked black cat.

While most of these so-called witches only went as far as amazing head trips in their own homes, Catholic leaders found it convenient to blame warfare, social unrest, famines, and even the plague on witchcraft. While the origins of the folk tales are hazy, it’s likely the Swedish clergy exaggerated stories about these women flying from their homes on Maundy Thursday to celebrate the Witches’ Sabbath, called Blåkulla (pronounced “Blockula” and not related to Blacula, the black Dracula) to make them more salacious and buzzworthy. Blåkulla was said to take place at a secret locale, possibly an unpopulated island in the Baltic Sea called Blå Jungfrun (meaning “Blue Virgin”) or on the mountain Blåkulla (“Blue Mountain”) near Marsstrand. What happened at this nefarious event? Well, according to wild inventions of children, all sorts of shocking debauchery.

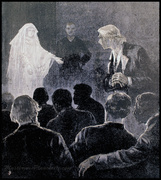

Witches arrive at the Devil’s Sabbath with cats and coffee in tow in this vintage postcard. (Via MetroPostcard Blog)

In a 1680s book on witchcraft called Saducismus Triumphatus, Anthony Horneck translated the testimonies of two Swedish children supposedly kidnapped by witches into English, which describe witches taking a magical flight to arrive at “a delicate large Meadow, whereof you can see no end.” As they traveled deeper into the meadow, they claimed, they arrived at the Devil’s house, which features a long banquet table and a second room with “very lovely and delicate Beds.”

The Devil wore “a gray Coat, and red and blue Stockings: He had a red Beard, a high-crown’d Hat, with Linnen of divers Colours, wrapt about it, and long Garters upon his Stockings.” At the Sabbath, “the Devil used to play upon an Harp before them, and afterwards to go with them that he liked best, into a Chamber, where he committed venerous Acts with them: and this indeed all confessed, That he had carnal knowledge of them, and that the Devil had Sons and Daughters by them, which he did Marry together, and they did couple, and brought forth Toads and Serpents.”

All Easter weekend, fearful villagers would light special evergreen branches in their fireplaces to smoke out or burn the witches who might have gotten caught or fallen asleep in their chimneys, according to Sara Di Diego in On Faith. (After all, the returning witches were probably drunk and/or bloated from their hedonistic revelry.) Bonfires would be lit on Holy Saturday to keep evil at bay. The witches who made it home safely were thought to attend to church Easter morning and try to blend in with the faithful, writes Donna Seger on Streets of Salem, only exposed when they said the prayers backward.

Some thought Easter Witches were shape-shifters who could turn into animals, as seen in a 1950 Curt Nystrom Stoopendaal postcard.

Eventually, the stories of children who claimed to have been kidnapped, such as the ones in Saducismus Triumphatus, led to massive anti-witch hysteria in Sweden and other countries between the 16th and 18th centuries. From 1668 to 1776, Petrulis explains, roughly 200 women were tried and sentenced to death by the Kingdom of Sweden, often by a gruesome beheading.

A few generations later, the horror of the witch hunts faded in the collective memory, and the formerly fearsome figure of the “Easter Witch” (påskkärring) became quaint and cuddly in the eyes of the Swedes. Petrulis supposes industrialization made its citizens nostalgic for rural folk superstitions, while the Romanticism of the Victorian Era put a positive spin on Pagan rituals. According to Pamela E. Apkarian-Russell in “Antique Trader,” witches became a part of the tradition known as “mumming” or “guising,” where people would don masks or face paint and gallivant about during Catholic feasts or parades like Easter. The mythology morphed to say that if a witch perched on your roof on Maundy Thursday, she was bringing you good luck. The Easter Witches’ male counterpart was the Easter Troll (påsktroll or påskgubbar), the formerly treasure-hoarding, presently flower-loving ogre.

Like any modern woman with many things on her plate, Apkarian-Russell explains, witches were said to love coffee. Similar to a Santa Claus for grown-ups, an Easter Witch on her way to Blåkulla would pause on the roofs of various homes to bring the occupants blessings of prosperity and joy, and leave hot copper pots of black coffee on the stoves. According to superstition, the blessed would note their food got a little tastier and in general they felt shielded from mishaps. Meanwhile, the kind witches were on their merry way to their Sabbath, which, by then, was described as an event more akin a giggly caffeine-fueled slumber party—full of food, singing and dancing—than a Satanic orgy.

Turn-of-the-century illustrator Jenny Nystrom defined the image of the Easter Witch. Two farm-wife-like hags nurture a cat at Blåkulla on a classic Nystrom postcard. (Via Art Side)

In the mid-19th century, children began to disguise themselves as witches on Maundy Thursday wearing headscarves, painting red circles on their cheeks, and carrying copper kettles. Then, Petrulis writes, they would go from house-to-house delivering handmade good-luck tokens, usually a sprig of pussy willows, in exchange for candy. The sprigs would be used by farmers to herd their cattle, in hopes the gesture would bring them fortune over the summer. When the children could not find pussy willows, they made their own cards to give out.

When lithography printers like Axel Eliassons in Stockholm began publishing holiday cards in the late 19th century, the Easter Witch—usually a happy elderly hag dressed like a Swedish farm wife in aprons and headscarves—became a standard character on often-comedic “Glad Påsk” (or “Happy Easter”) postcards. The printers also made smaller cards for the children to deliver. Influential Swedish illustrator Jenny Nystrom is credited with redefining the Easter Witch with her colorful and humorous turn-of-the-century cards. She then inspired Ingeborg Klein, Lars “Lasse” Carlsson, Sigrun Steenhoff, and her son Curt Nystrom Stoopendaal to come up with their own Easter Witch greetings.

Around the 1950s, Easter Witches became pin-ups. (Via On Faith)

As pretty-girl and pin-up art grew popular from World War II to the 1960s “Playboy” era, the witches on Glad Påsk greeting cards became younger, prettier, and progressively sexier. Like Mid-Century Santas, Easter Witches adopted modern means of transit, such as cars, airplanes, and rocket ships, and some found themselves in all sorts of slapstick situations, like getting entangled in television antennae or telephone wires.

Today, Swedish children still dress as witches for Easter celebrations on Thursday or Saturday, wearing brightly colored headscarves, rags, and old oversized skirts and dresses. But others go for popular Halloween costumes like Harry Potter or “Star Wars” characters. The kids often give out store-bought cards in exchange for coins, rather than candy. Even though the Swedish now eagerly await the arrival of an Easter Witch the way we do the Easter Bunny, they still burn bonfires and shoot off fireworks, which used to be a means of scaring the poor hags off. Sometimes even good witches can’t catch a break.

The War on Christmas Cards: Dead Robins, Used Paperclips, and Other Secular Greetings

The War on Christmas Cards: Dead Robins, Used Paperclips, and Other Secular Greetings

Ghosts in the Machines: The Devices and Daring Mediums That Spoke for the Dead

Ghosts in the Machines: The Devices and Daring Mediums That Spoke for the Dead The War on Christmas Cards: Dead Robins, Used Paperclips, and Other Secular Greetings

The War on Christmas Cards: Dead Robins, Used Paperclips, and Other Secular Greetings 20 Halloween Costumes So Unsexy, They're Downright Scary

20 Halloween Costumes So Unsexy, They're Downright Scary Easter PostcardsThe earliest known depiction of the Easter bunny in the United States was a…

Easter PostcardsThe earliest known depiction of the Easter bunny in the United States was a… Easter CollectiblesEaster is generally thought of as the celebration of Jesus’ resurrection, a…

Easter CollectiblesEaster is generally thought of as the celebration of Jesus’ resurrection, a… Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Thank you for the article. It was enlightening! I never thought about Easter around the world. Only thought of Easter in the states. So again, thank you!

Excellent article. I will show it to my grandkids to give them an idea of how we looked out through the window on Thursday night to see all the witches flying by.