With all the hand-wringing over anonymous commenters and social-media trolls, you’d think the Internet is to blame for all the woes of humanity. After all, what could people do with their ugly, mean thoughts before they had Yelp, Reddit, or Tumblr to help broadcast them? But as far back as the 1840s until the 1940s, they could send them in a Vinegar Valentine. Yes, that’s right. For almost as long as Valentine’s Day has been an insufferably sappy day celebrating romantic love, it’s also been a day for telling everyone else exactly how much you don’t love them—with an anonymous poem sent via post. [Click to see slideshow]

“We can’t be nice all the time. And the culture of ‘think positive and put on your best smile’ is quite wearing after a while.”

At first, it’s easy to demonize the senders as the worst sorts of trolls or bullies. I mean, some of the most horrifying Vinegar Valentines actually suggest the recepient kill him or herself. But then, if you look at the more light-hearted Valentines, some of them start to seem like a good idea. Have you ever had a haughty saleslady scoff at you for being poor? Have you ever had to listen to a pompous windbag carry on when he doesn’t have any idea what he’s talking about? So many people are blithely unaware of their obnoxious behavior. Wouldn’t it feel great to tell them off, consequence-free?

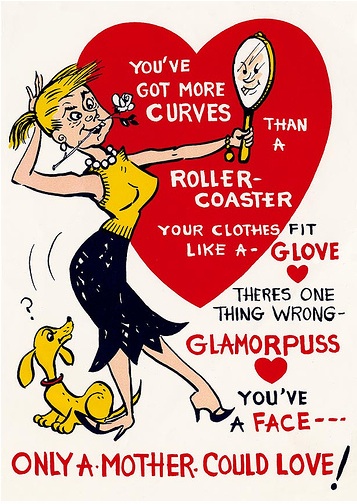

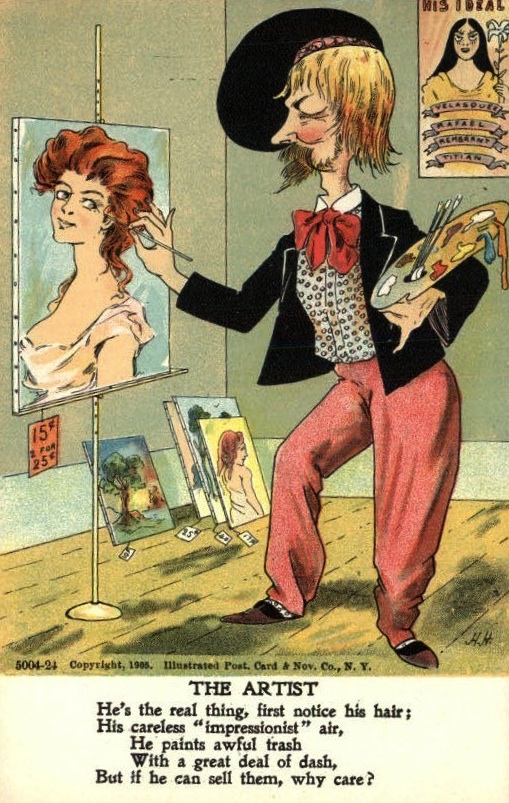

Top: Some Vinegar Valentines, like this 1940s American example, were meant to reject romantic advances. Above: Others, like this postcard from the 1910s, were meant for people in your day-to-day life.

Annebella Pollen, a lecturer in art and design history at University of Brighton, U.K., first discovered Vinegar Valentines when she was researching a project on love and courtship for the Royal Pavilion & Museums, Brighton and Hove. In the back of a stationer’s sample book from 1870, she discovered 44 cheap, single-sheet, insulting Victorian Valentines with a comic sketch and a few lines of verse. These Valentines made it into a 2008 exhibition called “On the Pull”—British slang for pursuing sex—and became the foundation for her further research into the subject. She explained to me what she’s found.

Collectors Weekly: Specifically, what you would categorize as a Vinegar Valentine?

Pollen: I’d say it would be a cheaply made card, with a printed satirical image that mocks the recipient and has a little doggerel verse underneath, usually four- or six-lined, describing some aspect of their personality and dismissing it. I like the term “vinegar” because it describes the opposite of the sweet sentiment of nice Valentines. They can vary from being a little bit tough to being absolutely bitter at their most extreme.

There were lots of different types produced; some of them would be on black backgrounds with quite colorful images printed on them. Some would be very basic wood cuts, a bit like very early street literature, where the image is coarsely rendered. There’s a whole range of British and American examples from the 1840s to 1940s. The aesthetic changes, but really, what remains the same all the way through is the sentiment—or lack of it. For example, the women who are pilloried in them over the course of 100 years are wearing different outfits, but they’re still mocked for how they look, whether they’re wearing a crinoline and a bustle or a skin-tight dress.

Collectors Weekly: And they were intended to reject romantic overtures?

Pollen: Yeah, but not only that. There were so many different kinds. You could send them to your neighbors, friends, or enemies. You could send them to your schoolteacher, your boss, or people whose advances you wanted to dismiss. You could send them to people you thought were too ugly or fat, who drank too much, or people acting above their station. There was a card for pretty much every social ailment.

Collectors Weekly: It seems like some of these were used to reinforce social mores.

In 1910s, an anonymous postcard might berate a couple, if the woman were perceived as dominating the man. The same sort of arguments were made against women’s suffrage.

Pollen: You have to remember that often they were sent anonymously. They were to say “Your behavior is unacceptable.” For example, there are quite a few cards that mock men with babies on their laps as being henpecked—the kind of thing now we would think was a man doing the right thing by taking his share of child care. But these cards were specifically designed to make the man seem emasculated and disempowered by being left holding the baby. Or there’d be images of women holding rolling pins, threatening their husbands.

The people sending such cards were usually not either one of the couple. It wasn’t the wife sending to the husband or the husband sending to the wife. It was somebody outside, looking in at their relationship and saying, “This doesn’t conform with what’s expected.” In that way, they did enforce social norms. Sometimes they seemed to be saying, “Change your behavior, or else.” There’s almost this threatening element to them.

Collectors Weekly: Do you think contemporary recipients would be surprised at their tone?

Several cards from this 1940s Vinegar Valentine series suggests that the recipient kill his or herself for some small offense.

Pollen: Yes, some are quite shocking. The cards are quite a surprise to those who think the past was always so safe and the present is so very daring, and that we’re much more libertarian now than we have ever been in any other period in time. I think we only have to look back at this sort of stuff to see that that’s not the case.

Nobody was safe, really, from Vinegar Valentines. There are some that insult alcoholics in a way that we would find completely unacceptable. Today, few would send a mass-produced card to someone they know is an alcoholic. We are fine with irony, but insulting someone for their drinking habit and actually meaning it? That’s the difference.

Mocking alcoholics was considered socially acceptable, even in the 1940s, as this Panoco/Doubl-Glo card shows.

There are a lot of the comic cards produced now, but they are not meant to be taken seriously. That’s why you can call somebody a bitch in a card, because you don’t actually think they’re a bitch. But in the Victorian valentines cards, it seems that you would send it to somebody who you’d actually have a serious problem with. That’s how I read them, anyway.

Collectors Weekly: The thought that popped into my head is that people have always been awful.

Pollen: Anonymity allows that, doesn’t it? Even now, people can leave comments on the Internet with impunity. It definitely offers you some cover and power, without responsibility. It’s quite interesting because people think, “Oh, new technology forces this upon people; it brings out something that wasn’t there before.” But it’s actually just the new medium for what’s always been true—as you say, some people have always been nasty.

Collectors Weekly: Do you know when the first vinegar valentine was produced?

A rare Vinegar Valentine from the 1860s points out the grim reality of a physician visiting the Civil War battlefield.

Pollen: I don’t know the exact date of the very first one, but they certainly predate mass-production. The earliest cards that I have been able to locate seem to date from about the 1840s, maybe even the 1830s. But the thing about Vinegar Valentines is that few people would have held onto them. So there are few collections of them anywhere because unlike a precious memento sent to you by a loved one, you probably wouldn’t keep it under a pillow or press it into an album. You would screw it up and throw it away. So unless you can find collections that were compiled by stationers or by collectors at the time, it’s very hard to trace the complete history of them.

Vinegar Valentines were mass-produced on a huge scale; they were very, very cheap and very abundant. However, they weren’t bought and sold by a section of the population who had the means to preserve things, either. People who preserved objects in the Victorian era are people who’ve had heirlooms to pass down, and the lived in secure homes where they could store things in dry conditions. These cards weren’t aimed at that kind of culture, really.

Collectors Weekly: So the first commercial Vinegar Valentines appeared before postcards were introduced in 1896?

Men were not immune to the Vinegar Valentine attacks, like this one mocking a bald guy in 1907.

Pollen: Yes, in the early days, they were not what we think of as cards. They were single sheets of paper. At the very beginning of postal delivery, pieces of paper were folded on themselves and sealed with a bit of wax because it was more expensive to put a folded object in an envelope. Mass-produced Vinegar Valentines were really popular from about the 1840s to about the 1880s. In the very early days, going back to a time in postal history before the prepaid stamp, the person who received it paid for it. With these Valentines, it meant that the person who got this really horrible note actually paid for the insult. So you’re insulting them further by getting them to cough up for it.

They seem to have had a bit of a revival during the Golden Age of picture postcards [1896-1917]. I’ve also seen some from the interwar period, between World War I and World War II. They have different styles over time, but the basic mocking message—from playfully mocking to downright insulting and horrible—carried on. They’ve usually got a typical format, which is a caricature of the person to whom it’s being sent and a little verse at the bottom. That format lasted at least 100 years from what I’ve seen.

Collectors Weekly: On eBay, people often call these cards “penny dreadfuls,” but is that the correct term?

Pollen: “Penny dreadfuls” is a collective general term used for cheap literature sold on the streets during the 19th century. And it could be salacious in its content, containing stories about gruesome murders, or news articles, or folk songs. These appealed to the newly literate working-class population, and they are called “penny dreadfuls” because the quality and the content were not of the highest order. They were really cheap. Often, they don’t have anything to do with Valentine’s at all. They were sold year round on the street.

Collectors Weekly: Can you tell me a little bit about the Victorian Valentine’s Day tradition?

Women have been berated for their looks for a very long time. This 1940s card is just another example. Via rickstimeonearth.blogspot.com.

“People think, ‘Oh, new technology brings out something that wasn’t there before.’ But some people have always been nasty.”

Pollen: It seems to me that it was much, much bigger than our Valentine’s traditions today—at least here in England—which are quite substantial. We assume that commercialization has expanded on an exponential upward curve over time. But Valentine’s Day became an absolutely massive craze starting in the 1840s, and then by the 1880s, it seemed to be going out of style again. The number of different kinds of Valentine’s cards that you could buy in the Victorian era is really phenomenal. You could buy so many novelty formats, such as ones that had puzzles on them or ones that would pop up.

I even saw an exploding Valentine’s card, which is a bit like an English Christmas cracker. The more beautiful, sentimental, and heartbreaking ones could have been constructed from silver lacy paper, or featured cushioned, quilted paper with lots of embroidery and detail. Sometimes they’d be perfumed. The Vinegar Valentines, which ranged from cheeky to rude to absolutely nasty, were just one kind of the many available. So Victorian Valentines cut across all the different emotions and formats.

Collectors Weekly: Everyone likes to blame Hallmark for Valentine’s Day, but really, they just capitalized on it.

Pollen: This is my argument, absolutely. These things are often pre-existing traditions that companies capitalize on and expand. And in fact, looking toward the end of the 19th century, the enthusiasm for these kinds of cards subsided. People blamed the manufacturers, saying it was because Valentine’s Day is being overly commercialized, the same as people now saying that Christmas is being ruined by commercialization. People saw Valentine’s Day as being a noble Christian tradition that had been overtaken by commerce. But you can’t blame the manufacturers. They were simply building on existing Valentine’s traditions, even insulting traditions, which created the market for the cards they made. People were exchanging Valentines for centuries before the Victorians.

Collectors Weekly: Even the 19th century, did some people object to their tone?

This card from the 1930s addresses the problem of unwanted visitors.

Pollen: I did find articles in the press in which people were complaining about Valentine’s Day being ruined. The articles are very much couched in moral terms, blaming card manufacturers for overcommercializing the holiday and people of lower standing and coarse humor for upsetting the noble sensibilities of the good people of the world.

At the time, it was reported in one of the newspapers that someone had received one of these cards and killed themselves. That was when it was perceived as having gone way too far. Those extreme cases did signal the demise of the tradition. By the latter decades of the 19th century, Vinegar Valentines had fallen out of favor. But then they were revived again in the postcard era of the 1900s, so they didn’t stay down for long.

Collectors Weekly: Were they a form of bullying?

This Vinegar Valentine ranting about a public display of affection is a sheet of paper that you would fold and mail.

Pollen: I suppose they could be considered a form of bullying, at least in their most extreme forms. A lot of them are quite playful and cheeky, though. Most are kind of a fond dig in the ribs. Some of the more playful ones I saw might depict, for example, a father discovering a couple canoodling behind the rose bush and pouring cold water out of a watering can on them. That’s similar to the gentle humor you would find in an early silent film. So some show the age-old scenarios that are slightly risqué humorously delivered, rather than telling somebody they’re stupid and that no one will ever want to marry them.

It’s hard not to read our own contemporary morals into them, though, so they may have meant something quite different at the time. Some of them appear quite outrageous to our values now. As I said, we might now consider alcoholism to be a disease, but at the time it was clearly not considered in those terms, so we have to be a bit cautious about reading our own moral agendas into something from 150 years ago.

Collectors Weekly: Do you see a Vinegar Valentine revival on the horizon?

This Vinegar Valentine from the late 19th century calls out a terrible singer. From the Strong Museum of Play.

Pollen: One of my friends on Facebook is selling anti-Valentine’s cards this year. It’s being embraced again. Maybe it’s because people are forever seeking out new products to sell that haven’t been sold before—or that they think haven’t been sold before. Or perhaps Vinegar Valentines answer some kind of human need. We can’t be nice all the time. And the culture of “think positive and put on your best smile” is actually quite wearing after a while. You need a safety valve, so maybe an insulting Valentine’s card is a good way of letting off some steam. After all, anyone with any sort of critical faculties is going to find some of the sentimental aspects of Valentine’s Day a bit cloying and unpleasant.

More Vinegar Valentines

(To learn more about Vinegar Valentines, read Annebella Pollen’s “Love Letters and Hate Mail: Victorian Vinegar Valentines” at Brighton Museums and “The Valentine has Fallen Upon Evil Days” in “Early Popular Visual Culture.”)

Can't Buy Me Love: How Romance Wrecked Traditional Marriage

Can't Buy Me Love: How Romance Wrecked Traditional Marriage

All You Need Is Paper: Why Antique Valentines Still Melt Modern Hearts

All You Need Is Paper: Why Antique Valentines Still Melt Modern Hearts Can't Buy Me Love: How Romance Wrecked Traditional Marriage

Can't Buy Me Love: How Romance Wrecked Traditional Marriage War on Women, Waged in Postcards: Memes From the Suffragist Era

War on Women, Waged in Postcards: Memes From the Suffragist Era Valentines Day PostcardsToday, antique and vintage Valentine postcards from the Victorian and Edwar…

Valentines Day PostcardsToday, antique and vintage Valentine postcards from the Victorian and Edwar… Valentines Day CardsSaint Valentine, a legendary ancient Christian said to have been persecuted…

Valentines Day CardsSaint Valentine, a legendary ancient Christian said to have been persecuted… Vinegar ValentinesPretty much as soon as Valentines expressing sweet sentiments of love, frie…

Vinegar ValentinesPretty much as soon as Valentines expressing sweet sentiments of love, frie… Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

If only we could go back in time and make everyone as brittle and humorless as we are today!

What a wonderful Valentine’s gift, receiving this historical archive of sociology/Art. Thanks for helping us to see that corporations can only sell to us what we purchase. I will file this enlightening collection under “Comic, O the humanity”.

Delightful!!

Any record of the insulting penny valentines that showed up secretly on your doorstep on Valentine’s Day…they were drawings and verses printed on very cheap paper. As a child I can vividly remember getting one that was entitled STUCK UP

Ahhh..the “Drink Bleach” of their day..

nicely done — gave me several giggles — of course i usually stop at this site to read all the latest history you at CW have dug up — better than the “daily word” we use to have to hear at breakfast time while waiting for the bus — ok so i dated myself