Harmonica players will suck and harmonica players will blow, but mastering the harmonica is tougher than its diminutive size and simple mechanics suggest. “The harmonica is actually pretty hard to play well,” says harmonica virtuoso Mickey Raphael, who has shared the stage with Willie Nelson for the better part of 40 years. “If you have a harmonica in the right key for a song, you can play any note and it’ll sound good. But to be able play melody on it is a whole different skill set.”

“These companies don’t know anything about the players, to tell you the truth.”

Of course, it doesn’t help if your harmonica is so poorly made that you couldn’t play it well even if you were a pro, which describes the state of the instrument from the mid-1970s until the early 1990s, when Hohner, the largest harmonica manufacturer in the world, began to cut corners in the production of its ubiquitous Marine Band harmonica. Most critically, the tools used to punch the slots in the harmonica’s reed plates were sharpened less frequently, and steps were skipped in the tuning of the reeds themselves. These and other economizing decisions made the instrument virtually impossible to control, thanks to all the extra air that was now leaking through the reed plates. Hohner eventually corrected this error, but it took a ragtag group of harmonica customizers and music geeks from around the world to force the 150-year-old German firm to face the music.

Even if a musician gets his hands on a well-designed harmonica and learns to play it as fluidly and expressively as Raphael, it’s hardly a sure-fire ticket to the big time. Unlike windmill-arm guitarists (Pete Townshend), 360-degree drummers (Neal Peart), and flamboyant keyboardists (Elton John), harmonica players anchor themselves to a single spot on the stage, hunched over, eyes shut, their hands obscuring their faces as they huff and puff until they’re soaked to the skin with sweat.

It’s often not a pretty sight, and you don’t even want to know about the tonguing techniques employed to block certain holes while blowing out or drawing in, let alone a prolonged period of bloody lips. “That was kind of a rite of passage,” laughs harmonica maker and technician Kinya Pollard. “If your lips weren’t bleeding after a gig, you were considered a weenie.”

Above: Kinya Pollard, aka the Harpsmith, testing a harmonica in his workshop. Top: Mini harmonicas from Harland Crain’s collection. Makers include Hohner, Schlott, Koch, and Seydel.

Not surprisingly, kids everywhere aren’t exactly clamoring to learn how to play the harmonica, nor are the airwaves crowded with the instrument’s sometimes cheerful, sometimes melancholy, sound. Yet despite their low profile in the culture at large, following those decades of poor quality by Hohner, harmonicas are enjoying a full-blown renaissance right now, as major manufacturers and boutique customizers alike battle to perfect the beloved instrument. In a weird way, harmonicas are cool again precisely because they aren’t hogging the limelight, giving them an underground, back-to-the-roots cachet.

The full extent of this harmonica convergence will be on display from August 13 through 17, 2013, when the Society for the Preservation & Advancement of the Harmonica (SPAH) holds its 50th Anniversary Convention in St. Louis, Missouri. More than 500 harmonica players and aficionados from around the world are expected to attend dozens of formal and impromptu performances, as well as 80-plus seminars on every aspect of the harmonica you can imagine, from jazz techniques for chromatics to bending tricks for diatonics.

In case you aren’t hip to harmonica lingo, diatonics, commonly called harps or blues harps, are the small, 10-hole instruments made famous by musicians like Little Walter, who played Hohner Marine Bands in various keys when he joined forces in 1948 with Chicago bluesman Muddy Waters.

The Hohner Marine Band was introduced in 1896 and is probably the most commonly played harmonica in the world, which is why a tweak to its design in the mid-1970s had such profound repercussions.

Chromatic harmonicas usually feature 12 to 16 holes, plus a button on the side that allows the player to sharpen notes with a single push, extending their range to a full chromatic scale. Artists associated with chromatic harmonicas include classical musician Larry Adler, jazz maestro Toots Thielemans, and the multi-dimensional Stevie Wonder.

The current harmonica renaissance began sometime in the 1990s, around the time that enough serious players finally got fed up with what Hohner had done to its flagship diatonic in the 1970s, when the quality of the venerable Marine Band sank like a sack of rusty harps hurled into the Mississippi.

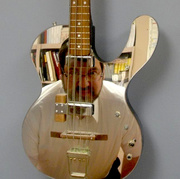

Hohner’s Thunderbird, designed by Joe Filisko, is basically a tricked-out, low-key Marine Band.

“I can’t remember exactly when it happened,” says customizer, teacher, and harmonica historian Richard Sleigh, “but when I was buying harps in the 1960s, and even in the early ’70s, they all seemed to work pretty good right out of the box. But somewhere in the ’70s, I found it harder and harder to find harmonicas that played well, and things got really bad in the ’80s.”

It may seem odd to peg the harmonica’s resurgence to its nadir, but when Hohner flooded the market with subpar harmonicas, it ultimately proved a boon to the instrument and its players. By the end of the 1980s and beginning of the ’90s, players were looking for answers. “That’s when Joe and I came on the scene,” says Sleigh.

“Joe” is Joe Filisko, the genius of Joliet, the harmonica customizer and technician whose last name is usually followed by the word “Method,” and whose signature is engraved on the cover plate of Hohner’s current top-of-the-line 10-hole diatonic harmonica, the Thunderbird, which Filisko helped design.

“Many a professional harmonica player came banging on my door,” remembers Filisko of the 1990s. Filisko was quickly gaining a reputation for his harmonica customization work—unlike your average tinkerer, Filisko had his own machine shop. “They were pleading for help. With the fantastic assistance of Richard Sleigh, I decided not only to figure out how to make harmonicas play better, but also to look at people’s playing styles to create the optimal harmonica and tuning for them. The goal, basically, was to increase the responsiveness of the instrument so it produced more music with less effort.” This combination of engineering harmonicas to optimize their performance and then tuning the instruments to suit a player’s style is known as the Filisko Method, even though Sleigh contributed greatly to it.

“Joe was the main force, but I worked with him for years,” says Sleigh. “The combination of the two of us working on the same problems created a lot of breakthroughs.”

Like most customizers, Richard Sleigh also plays.

For Filisko and Sleigh, no detail about the harmonica was too small. “Joe created tools and techniques to reshape the cover plates,” Sleigh says. “The idea was to make them look more like prewar Marine Bands, as well as to give the draw reeds more room to swing at the low end of the harmonica—on low-key Marine Bands, the reeds would actually hit the inside of the cover plate. So we did things like that, but mostly it was the reed work, which was based on everything Joe and I learned from whoever would talk to us. There were no books; it was all unknown territory.”

The immediate challenge facing Filisko and Sleigh, though, was to fix all those mid-1970s to early 1990s diatonic Marine Bands, the harp of choice for aspiring and professional blues musicians, who remain Hohner’s best customers. To understand how such a relatively small change to the instrument’s design could make such a big difference to its performance, it helps to know a little bit about how a diatonic harmonica works.

Diatonic harmonicas are built out of five basic pieces, which are stacked together like a sandwich (in fact, “tin sandwich” is just one of the instrument’s colorful aliases, “Mississippi saxophone” being another). In the center is the comb, the thick, rectangular piece of wood, metal, or plastic that you blow into or suck on. On the top and bottom surfaces of the comb are two matching reed plates, whose individual reeds are aligned over slots in the reed plates that correspond to the voids in the comb. Cover plates give the player something to grip, while openings at the back of the plates give the sound somewhere to go.

The reeds are the parts of the harmonica that actually make the noise. You can pluck one with your fingernail to produce a tinny note, or you can blow into, or draw air out of, a harmonica to set the reeds a-vibrating. In this context, that fingernail pluck is a single, mechanically induced vibration. Airflow creates thousands of such vibrations. The pitch, or note, of a reed is the same whether its vibration is due to a fingernail or the flow of air, but obviously the hands-off method of vibrating a reed will produce a different type of sound.

“On the road, I want a harmonica I can hammer nails with.”

How frequently a reed vibrates through its corresponding reed slot is a function of how big it is (the longer the reed, the lower the note and the slower the vibration) and what it’s made of (Hohner harmonicas have brass reeds, Suzuki makes its out of phosphor bronze, and many Seydel harmonicas are fitted with stainless steel reeds). This combination of mass and material causes a reed to eventually resist the air pressure exerted upon it by the player’s breath. Once the reed has been bent to its structural limit, it springs back, only to be pushed out or drawn in again, traveling back and forth through the reed plate, chopping the air with each vibration.

When the slot in the reed plate is just barely bigger than the reed, so that as little air as possible is passing through it, we call the result music. When the slot is too wide, the instrument will sound breathy and lifeless, and its player will sound like an amateur.

Kinya Pollard used a modified light box to check the gap between a reed and the slot it swings through. Too much light means too much air is getting through. He looks for a sliver of light, as seen here.

One of the main tasks of the harp tech, as people who like to tune, customize, and generally fool around with harmonicas are called, is to tune a harmonica’s reeds. But even before he can do that, the harp tech must check to see that the reed is positioned properly in its reed plate. Kinya Pollard accomplishes this essential task by placing a reed plate on a modified light box to produce a halo of light around the long sides and free end of the reed he’s tuning. The light he sees is a visual representation of the air that will pass through the instrument when it’s played.

“I’m looking for an equal amount of light on the left, top, and right sides of the reed,” Pollard says. “When there’s just a sliver of light around the reed, so that you can barely see it, you’ve got good compression, which means the player does not need to move so much air. It’s like achieving better action on a guitar. For harmonica players who play very expressively, with a lot of volume dynamics, you can hear the nuances if the harmonica is set up right.”

The problem, of course, is that centering reeds on a reed plate with tight slot tolerances takes time, and time in a manufacturing setting is money.

Ironically, in the mid-1970s, around the same time that Hohner was cutting corners on the Marine Band, it was building one of the best chromatic harmonicas ever made, the Hohner Professional 2016 CBH, whose initials are taken from the name of its designer, the great Chinese classical harmonica player, Cham-Ber Huang. But the 2016 chromatic was a prestige project, the sort of thing companies do to give themselves street cred. Lost in the shuffle, temporarily anyway, were the needs of its biggest customers, blues-harp players.

To solve the technical problem posed by the Marine Bands, Filisko and Sleigh tightened the tolerances of the slots using a technique called embossing developed by a harmonica player and customizer named Rick Epping (also referred to as sizing or burnishing, the technique essentially involves forcing the edges of the reed and the reed slot together, by hand, with a specially designed tool). In the late 1980s, Epping traveled to Hohner armed with a collection of old, sweet-sounding Marine Bands. Along with Steve Baker, who was a consultant to Hohner at the time and remains one today, Epping eventually convinced the company to redesign its most popular model. By then, though, there were countless poorly designed harmonicas floating around, which kept Filisko and Sleigh busy for years.

One of Brendan Power’s trademarks is to stretch ordinary Marine Band harmonicas. The one at the bottom is a regular Marine Band, while the two above it have been stretched to 12 and 14 holes respectively. Note how the numbers on the cover in the middle harp do not match the number of holes.

Of course, Filisko, Sleigh, Baker, and Epping were not the only people on the planet interested in improving the Marine Band harmonica. Half a world away, in Christchurch, New Zealand, Brendan Power, who’s known for his extreme harmonica hacking and alternate tunings, was adding an 11th hole to off-the-shelf Marine Bands. “Most diatonic harmonicas have 10 holes and most chromatics have 12,” Power says from his home in England. “I take a hacksaw, chop them up, and glue them back together in different sizes. I’ve made quite a few 13-hole harps, my ‘lucky 13s,’ which are basically 10-hole harps with an extra octave glued on the bottom, giving me an additional low range. I call them stretch harps.”

Kinya Pollard went in the other direction by reducing the size of off-the-self Hohners from 10 holes to seven. “I have small hands,” he says. “When you play amplified, you have to learn how to cup your hands around the instrument to be airtight in order to overdrive the microphone.” That’s the technique pioneered by Little Walter. “I found I wasn’t really using the top three holes on a regular harmonica, so I chopped them off. I call my harmonica the Mag7, short for Magnificent 7. Now when I play amplified, I can close my hands completely and get a very fat sound.”

For players with small hands, Pollard’s seven hole Mag7 is a good solution. This one has a Corian comb.

Pollard’s reference to amplification is just one example of the cultural challenges Filisko and Sleigh faced in the early 1990s. Retrofitting a harmonica with sloppy reed slots was relatively easy. The real victory, they knew, would be to figure out how to tailor every aspect of a harmonica’s design to the way people in the late 20th century actually played.

When Christian Friedrich Buschmann invented the harmonica in 1821, he assumed people would use the instrument for melodic folk songs. During the early part of the 20th century, harmonica orchestras and bands were all the rage (there were literally thousands of them), spurring the development of specialized bass, chord, and chromatic harmonicas. Novelty versions of the instruments in all shapes and sizes were also stamped out, festooned with gimmicks like bells and horns to attract new customers.

Harland Crain of St. Louis, Missouri, has a lot of these harmonicas. Truth told, Harland Crain has a lot of harmonicas, period—at 5,500 and counting, his collection is thought to be the largest in the world.

This very rare three-horn harp from Harland Crain’s collection was made in Klingenthal, Germany, in the early 1920s by G.A. Doerfel and distributed in the United States by F. Strauss.

“The majority of them are in good enough shape to be played,” Crain says of the instruments in his care, “but I don’t play a lot of the older ones. There might be spiders in them, for all I know.”

Crain began collecting harmonicas about 15 or 20 years ago, which, not coincidentally, was around the same time players started realizing that the old, pre-1970s Marine Bands played better out of the box than new ones. “That got around,” says Sleigh, “and suddenly everybody was looking for old harmonicas. The whole mania for finding antique harmonicas reached a fever pitch, and that’s also when other manufacturers began to jump into the scene. Lee Oskar got launched during that time, and a few other manufacturers got a foothold in a market that had been totally dominated by Hohner.”

Crain’s collection began through a family connection. “My brother-in-law, who does estate sales, gave me a call one day and said, ‘Hey, I’m over here at this house and there are about 30 harmonicas in a box.’ I bought them all. And then this other guy in town called me up and said, ‘Hey, I heard you bought some harmonicas at an estate sale. Why don’t you come over? I’ve got a collection.’ At the time, he was one of the top harmonica collectors in the country with something like 2,500 harmonicas. I had 36 of them, for crying out loud. So I got my little shoebox together and I went over to his house. I bought a bunch from him, and then I bought a couple of small collections, ‘small’ being in the 500-or-so range.”

Harland Crain says this Hohner Trumpet Call was one of six different models, and is probably the most valuable. It was made in the late 1920s.

Along the way, Crain learned a lot about old harmonicas. “Probably 80 percent of my harmonicas, maybe more than that, are German- and Austrian-based. Oddly enough, a lot of the early harmonica makers were also clockmakers. I guess the clock business wasn’t doing that well so they found another outlet for their ability to build intricate things, like brass reeds.”

In the beginning, Crain says, harmonicas were little more than glorified pitch pipes, “but by the late 1800s, they had figured out how to set the harmonica up so it had proper tone progression.”

For Crain, who plays a bit himself and counts many pro players as friends, the heyday of the harmonica was from 1910 to 1930, “plus or minus a few years,” he says. “They did everything,” he says of the manufacturers who made and marketed harmonicas during that era. “They even tried to attract children with gimmick harmonicas. I’ve got one called a coin harp. It’s a tubular thing, about four inches long, and on one end it has a little spring-loaded compartment where you can store five nickels. It’s just great.”

This mix of gimmick harmonicas from Crain’s collection, mostly from the 1920s, includes instruments in the shapes of baseball bats, cigars, pistols, and fish.

Crain has harmonicas in the shapes of zeppelins and pistols, pianos and guitars. He’s got harmonicas with trumpet-shaped cover plates designed to amplify the instrument’s sound (“it didn’t work very well”), as well as harmonicas with bells on them, “so you could play a German folk song with bell accompaniment.” He’s got Huck Finn harmonicas and Uncle Tom ones, too, harmonicas designed to only play certain chords, and others made to play specific songs (one of Crain’s favorites is a chord harp that’s good for little else than “God Save the King”).

Against this backdrop of novelty and gimmicks, serious musicians in the 1930s were pushing the instrument to its breaking point, tricking their harmonicas into hitting notes they weren’t even designed to produce.

Probably the most influential player from this period was Sonny Terry, a blind musician from the southeastern United States, who was already a force on the folk scene when he paired up with guitarist Brownie McGhee in 1941.

According to collector Harland Crain, this Beaver Brand (Hohner’s second label) University Chimes was probably made in Klingenthal in the late 1920s or early ’30s.

Ask just about any contemporary harmonica player who his heroes are, and Sonny Terry is usually the first name you’ll hear. “I discovered Sonny Terry when I was in my freshman year in college,” says Richard Sleigh. “It was on a recording called ‘Lost John,’ He really brought out its textures, and his timing was incredible. In many ways, he paved the way for a lot of modern harmonica players, with his emphasis on playing really fast and these incredibly exciting, rapid-fire licks. I call them controlled epileptic fits.”

Brendan Power was equally smitten. “I was a 20-year-old university student,” he recalls, echoing Sleigh’s experience. “Someone dragged me to a blues concert by Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee. I had never heard of them or listened to the blues, but I was so blown away by Sonny’s harmonica playing, I went out and bought a harmonica the next day. It became my obsession—35 years later, it still is.”

Like a lot of players, Sleigh started playing along with Sonny Terry’s solo on “Lost John.” Unwittingly, that simple act of mimicking taught him many of the most important harmonica breathing techniques. “I didn’t really piece it together until later,” he says, “but it gave me this incredible foundation. It’s really important to learn breath control, and playing Sonny Terry’s chord rhythms was a great way to get started on that.”

Among other things, Terry was known for his whooping and wailing, in which he’d mix his falsetto voice with notes on the harmonica. He was also big on train imitations, recreating the sound of a steam-train whistle and using chord rhythms to evoke steel wheels clattering down a track.

Terry’s playing was mind-blowing, which is why it’s downright scary to consider the sounds he might have produced if he’d had the opportunity to play a Filisko Method harmonica designed with his style in mind, from its shape and mechanics to its tuning.

“When Sonny Terry started playing in the 1930s,” Sleigh says, “Marine Band harmonicas were tuned at the factory very close to pure ‘just intonation.’” Just intonation is a type of tuning designed for playing chords rather than single notes in a melody. “In the ’60s,” he continues, “Hohner started tweaking the formula, bringing a few of the draw notes up closer to what you might call standard pitch, to make melodies sound more in tune. But most of the classic blues recordings from the 1930s to ’50s featured harmonicas tuned to ‘pure just’ to make the chords sound smooth.”

A few Mag7s in Kinya Pollard’s harp case.

“Tuning’s a very deep subject,” says Brendan Power, “but basically there are two main ways of tuning a harmonica. One way is to tune it to tempered tuning, where if you look at your tuner while you are tuning a reed, the dial would be in the middle. Every reed would look like that. When you tune a harmonica for chords, though, using just intonation, some reeds will be flatter or sharper in relation to others in order to give you a nice, sweet chord. Jazzier players prefer tempered tuning. Blues and folk players prefer just tuning. It all comes down to your ear, really. If it sounds good to you, then that’s the right tuning.”

“Chordal versus individual-note playing is really a preference of the player, as well as the listener,” agrees Pollard. “The most popular tuning I do is called ‘compromise just intonation,’ which is for players who do a lot of melodic lines as well as some chordal playing.”

That’s how Mickey Raphael gets most of his harmonicas tuned. A Hohner endorsee and a master of the Hohner Echo Harp, which gives so many Willie Nelson tunes their signature sound, Raphael also owns harmonicas made or customized by Filisko and Power.

Mickey Raphael and the harmonica case he travels with on the road with Willie Nelson. Note the row of Hohner Echo Harps on the left.

“When I get a harmonica from Joe,” Raphael says, “I ask him to tune it the way he thinks it should be. He knows my playing, so I let him decide. He makes me a kind of compromise between just and regular tuning, because he knows I want that chord to sound nice, but I’m also going to be playing lots of single notes. I keep asking Joe to tune me up a ‘just-tuned’ harp,” Raphael adds, “and he goes, ‘Nah, you don’t want that.’”

Which brings us back to Sonny Terry’s diatonic harmonica: Not only was its tuning almost certainly less than optimal for his playing style, it was definitely not designed to showcase bends and overblows, which describe sounds that are flatter or sharper than the note you are trying to play, but still within the tuned range of the reeds below and above a given hole.

“When they first started making harmonicas,” Sleigh says, “people were mostly playing German folk music. Bending notes was seen as a problem. In fact, some harmonicas were made so you couldn’t bend the notes on them at all. That was considered an improvement for certain styles of music.”

Little Walter was famous for his years with bluesman Muddy Waters and for amplifying his harmonica with a taxi dispatcher’s microphone.

Once players figured out how to bend notes, though, the genie was out of the bottle, and the guy who’s generally credited with shattering the bottle is Little Walter. In fact, Little Walter blew up the acoustics of the instrument itself when he amplified it to the point of distortion by cupping his hands tightly around the bullet-shaped body of a taxi dispatcher’s microphone, to “overdrive” it, as Pollard puts it. The music world has not been the same since.

“If your lips weren’t bleeding after a gig, you were considered a weenie.”

Collector Harland Crain’s fondness for instruments from the first third of the 20th century notwithstanding, many people today associate harmonicas with the blues of the Little Walter era. The heyday of that musical genre, however, was brief, lasting only from the end of World War II until the mid-1950s, when Chuck Berry married the basic rhythms of the blues with a peppy country sound to create music that was 100 percent sunshine and fun, which most people know as rock ‘n’ roll. By the 1960s, blues music was seen as a style whose heyday ended sometime in the Eisenhower administration. Rock ‘n’ rollers respected the blues as a kind of roots music for their new genre, but it was hardly a driving force in popular culture, although harmonica players like James Cotton, Junior Wells, Charlie Musselwhite, and Paul Butterfield more than kept the art form alive.

“I take a hacksaw, chop them up, and glue them back together in different sizes.”

For the remainder of the 20th century, harmonicas were a key ingredient in the blues and some strains of country music (a tip of the cowboy hat to Charlie McCoy for that). Occasionally, the instruments were even invited to feast at that beggar’s banquet known as pop.

In fact, one of the first modern harmonica hits coincided with the first hit single for The Beatles in 1962, when John Lennon played a jaunty harmonica melody on “Love Me Do.” In 1963, a 13-year-old named Stevie Wonder made his smash debut with “Fingertips (Pt. 2),” thanks in no small part to Wonder’s impromptu harmonica hijinks at the song’s end (you can almost picture little kids everywhere cheering when he snuck in a quick verse of “Mary Had a Little Lamb”).

By the end of the decade, the harmonica had been fully embraced by rock, the bastard-child of the blues. In 1969, Mick Jagger put his famous lips to a harp for the blues-infused “Midnight Rambler,” while Robert Plant channeled his inner Sonny Boy Williamson for Led Zeppelin’s version of “Bring It On Home.”

“Many a professional harmonica player came banging on my door.”

The first half of the 1970s was even better for the instrument. In 1970, former Lovin’ Spoonful folkie John Sebastian sat in on a Doors recording session to give “Roadhouse Blues” some much needed gravitas, and in 1971, the J. Geils Band put the instrument front and center with Magic Dick’s performance on “Whammer Jammer,” which would be even more famously reprised on a live album, “Full House,” the following year.

Also in 1972, artists as diverse as Neil Young and David Bowie had hits with the harmonica (“Heart of Gold” and “The Jean Genie” respectively), while in 1973, pianist Billy Joel ironically shined a spotlight on the harmonica with “Piano Man.” Stevie Wonder was back in 1974 with “Boogie On Reggae Woman” and in 1975 Lee Oskar of War released “Low Rider.” Today, Oskar sells a line of well-respected harps that bear his name.

After that, the instrument sort of went into hiding. Mickey Raphael helped make “On the Road Again” a hit for Willie Nelson in 1980, and Raphael sat in with Motley Crüe for its 1985 cover of “Smokin’ in the Boys Room.” That same year, John Cougar Mellencamp used a harmonica on “Small Town,” and in 1995, John Popper of Blues Traveler blew everyone away with “Run-Around.”

Since then, the instrument has been largely absent from the pop charts, although the dearth of harmonica hits has not impeded the instrument’s renaissance.

One particular fixation has been the instrument’s comb, which is the piece in the center of the harmonica that the reed plates are attached to. For manufacturers, experimenting with comb materials like bamboo or composites made of wood fiber and epoxy carries less risk than monkeying around with the reed plates. For harmonica customizers, the comb is a relatively simple piece to build from scratch.

“It’s sort of like a cottage industry now,” says harp tech Kinya Pollard. “People all over the world are making different types of combs. Aviation-grade aluminum is extremely popular, as is brass. There’s clearly a weight difference, and it’s a little too heavy for me—I slammed it into my teeth a couple of times. I’m just not used to it.”

Randy Sandoval of Genesis Harmonicas makes harmonica combs out of Corian, a material most people associate with kitchen countertops. It’s waterproof and can be sanded perfectly flat, giving it a tight seal with the reed plates that are attached to it.

At the other end of the weight spectrum is plastic. “The comb in the Hohner Special 20 is made out of a plastic called ABS, which plumbers know,” Pollard continues. “It’s kind of a rubberized plastic that has a lot of give to it, lasts forever, and is completely water and airtight. I can see why Hohner likes to use ABS for its combs because it’s probably very economical to do so. It also happens to be one of my favorite combs.”

You wouldn’t think a pro like Mickey Raphael would have anything to do with plastic combs, but he’s also a fan. “I play hard, two hours a night, five nights a week,” he says. “I’m kind of abusive. In the older harmonicas, the comb was made of wood, and it would swell when it got damp or wet. In some of the places we’re playing, the air is so thick I have to play the plastic-comb harmonicas. I use ’em outdoors, too. But I play a different harp when I’m in the studio, the Marine Bands with the wooden combs. In the studio, I can baby it. On the road, I want a harmonica I can hammer nails with.”

Reeds are also hot. “The new Suzuki SUB30 Ultrabend has three reeds in each chamber,” says Pollard. “I don’t think it’s ready for prime time yet, though. I can’t even play it well.”

As you might expect, Brendan Power, the hacker who adds extra holes to his harmonicas, loves the idea of a harmonica with extra reeds. “I’ve got a new venture called X-Reed Harmonicas,” he says. “It’s for this whole new family of harmonicas.” Some of the products Power has developed are actually designed to make the Suzuki SUB30, well, playable, but his most recent creation is his own ChromaBender, which is manufactured for Power by Hering in Brazil. “It’s a harmonica with extra reeds,” Power explains. “Under normal play, the extra reeds sit passively in the harmonica, but when you bend on the low notes, they come to life.”

And then, of course, there’s Hohner, which is still the big dog of the harmonica world, and has, by most accounts, learned well from its hard lesson with the Marine Band. “The Marine Bands they’re making now,” says Richard Sleigh, “are on the level of anything they did in the past. In many cases, they’re better.”

“Hohner has really stepped up its game,” agrees Joe Filisko. “They’ve tried especially hard to make harmonicas as much like what a professional harmonica player would want as possible.” The first evidence of that was the Marine Band Deluxe in 2005, which is when Steve Baker finally persuaded Hohner to adopt construction ideas pioneered by Filisko and Sleigh. The Crossover quickly followed, and both benefited greatly from Rick Epping’s successful efforts to get Hohner to retool and improve reed-slot tolerances. “On the coattails of that,” adds Filisko, “they introduced the Thunderbird, which is a Crossover Marine Band with low tunings. It’s kind of an experiment. I think they’re just putting it out there to see what happens.”

When it comes to low-tuned Hohners, Filisko is more than a casual observer. “I’d been making low-tuned harmonicas for quite a while,” he says, “maybe 20 years before they came out with the factory one, but I really wasn’t using them that much when I played, especially when I started recording. It didn’t seem right to record with a harmonica that you couldn’t buy anywhere. When Hohner decided to come out with a range of low-tuned harmonicas, they used some of my engineering ideas, especially pertaining to the cover-plate design, to allow it to play more musically. To my great fortune, they decided to give me credit.”

And that’s important, even to a guy as renowned as Joe Filisko, because in the harmonica world, all roads eventually lead back to Hohner. “That’s Adam from Hohner calling me right now,” apologizes Mickey Raphael during our interview, before taking a call from his personal customizer at the Hohner factory. Five minutes later, Raphael is back on the line, and we’re talking about Hohner again.

“These companies don’t know anything about the players, to tell you the truth,” Raphael sighs. “Adam’s a great guy, but the guys running the company? I don’t think they’ve got a clue.”

As proof of their cluelessness, Raphael tells me a story about the time he met one of Hohner’s higher-ups, who had come to a Willie Nelson concert presumably to meet Raphael, who has probably done more than any musician in the world to keep the ethereal tremelo sound of the Hohner Echo Harp alive. “He came to the gig and handed me a harmonica for Willie, a Tiffany harmonica with Willie’s name on it. And I said, ‘Dude, you know I’m the one who plays the harmonica, right?’ Willie couldn’t care less about stuff like that, you know? I gave it to one of our roadies.”

(Thanks to David Barrett and Brad Kava for putting me in touch with Harland Crain and Kinya Pollard, who sent me to Brendan Power and Richard Sleigh, who insisted I talk to Joe Filisko. Thanks to Helen for Mickey. For an update of this article, read “The Return of the Harmonica” at Craftsmanship.net.)

Youngbloods Guitarist Banana Talks Vintage Banjos and the Late Earl Scruggs

Youngbloods Guitarist Banana Talks Vintage Banjos and the Late Earl Scruggs

Say Ahhh: An Oral Surgeon's Quest to Reimagine the Garage-Band Guitar

Say Ahhh: An Oral Surgeon's Quest to Reimagine the Garage-Band Guitar Youngbloods Guitarist Banana Talks Vintage Banjos and the Late Earl Scruggs

Youngbloods Guitarist Banana Talks Vintage Banjos and the Late Earl Scruggs The Blues Rocker's New Secret Weapon? An Electric Cigar Box Guitar

The Blues Rocker's New Secret Weapon? An Electric Cigar Box Guitar HarmonicasHarmonicas are often described as the most popular instruments on the plane…

HarmonicasHarmonicas are often described as the most popular instruments on the plane… Musical InstrumentsWhether it's a clarinet or an accordion, a piano or a trombone, musical ins…

Musical InstrumentsWhether it's a clarinet or an accordion, a piano or a trombone, musical ins… Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Wow, what an article.

Great article, Amazing videos , Great players !!! Thx for putting this together!

Very curious that the Hohner XB40 designed by Rick Epping isn’t mentioned. Why?

Interesting read. I am anxious to explore the world of custom harps. I have been using Special 20’s for years as the Marine Bands swelling of the comb irritated me and “did” make my lips bleed…grin.

rp

A heck of a good article. I am a 76 year old guy, coming back to playing the harmonica (badly!) after a fifty year layoff.

Like Chris Moran I found it curious that Rick Epping’s XB40 was not mentioned. Apart from being a gifted technician Rick is also an inspirational player and teacher.

Wonderful article. When I started collecting harmonicas 12 years ago it was Harland Crain who helped and encouraged me. I saw his collection 4 years ago and was totally amazed. Thanks for this great article that covers so much of the joy of the harmonica.

An inredibly well written and intelligent article that covers a ton of ground. I have been playing harp for 40 years + and now understand why the learning process in the 70s and 80s was so painful. I am very happy about the current state and direction of the industry. Folks starting out now really have a tremendous aadvantage due to improved harp technology, the amazing generosity of the harp community via YouuTube, the internet generally and the many flourishing harp affectionate communities, ArtistWorks with Howard L, David B. and BluesHarmonica.com and all the other folks and efforts mentioned in the article. Fabulous writing! Thank you!

John Ingham

MasterHarp.com

WOW!!!

Great job. Not to worry

If you tried to mention ever different harmonica or player it would take years.

Regards Harley

Great article! And I loved the videos, too. Watching the guy tune the harp was fascinating. Tons of stuff in here I didn’t know. I will be sharing this.

One thing I have to nitpick about, though. You talk for several paragraphs about the history of the instrument in popular music, and how it was used by notable artists like Stevie Wonder, John Lennon, Mick Jagger, and so on. And you talk about how these artists affected perception of the instrument.

And yet, you never mention one of the most iconic harmonica players of them all, Bob Dylan. I know that his primitive technique on the instrument is derided by many with as much scorn as some deride his singing. I am a fan of both his singing and harmonica playing, but regardless of where you stand on that, the point remains. The image of Bob Dylan onstage with an acoustic guitar and a harmonica rack is one of the first things many people will think of when you mention the instrument, and he arguably had more to do with putting the instrument in peoples’ minds, and on the radio, then most of the other artists you mention.

Best article I’ve ever read about harmonicas! Interesting to note how many references to Sonny Terry/Brownie McGhee’s college tour 40 years ago. As a novice listening to Paul Butterfield and Steve Miller (my first harmonica fell of the stage at one of his concerts) I saw Sonny in Athens, Ohio and sat on the floor about 5 feet in front of him; changed my life forever! This article explains my long search anything better than the Hohner marine band of the 80’s & 90’s…then the Special 20’s, finally to Lee Oscar’s harps years later. Many thanks for this wonderful article!!

A great article. I have boxes of bad harps that I learned to tune and repair during the 70’s and on, now I know why.

Kinda Pollard’s tuning equipment looks pro,

where did he get it? Richard, you always have

great things to share, and I still use your tuning book,

Thanks,

Rog

Certainly the best article about harmonica I have ever read, with incredible insight into the mechanics of the harmonica which I have never seen explained in such detail before. But I did some information that I wish had been included, such as Lee Oskar’s different tunings and his innovation of selling replacement reed plates. Suzuki also deserves some mention for its innovations in recent years.

I will be sharing this article with my harmonica buddies around Asia, where I’ve been living since 1986. We got some really great players over here.

This article makes me very sad that I will not be at SPAH’s 50th — certain to be one of the ost important harmonica gatherings in history.

Thomas “Tomcat” Colvin

http://www.bluesasianetwork.com

Hi Roger:

Kinya uses a Cleartune Chromatic Tuner on his phone (you can get one in the app store for 3 or 4 bucks) and a Sjoeberg Harp Tuner on his bench. Here’s more info on that:

http://www.masterharp.com/

Best,

Ben

Fine article about the Marine Band and the people who helped save it. Another who was dedicated to this model and pushed for its resurrection is ace harpman Kim Wilson.

A must-read for any harmonica fan, and a significant scholarly work about American music in general is “Harmonicas, Harps and Heavy Breathers, the Evolution of the People’s Instrument” by my college friend, Kim Field. Kim is an expert player himself and a friend of Joe Filisko.

Another Joe Filisko creation—which he accomplished with the help of Boise, Idaho guitar maker John Bolin and the legendary Billy Gibbons of ZZ Top—is the “Muddy Wood” Marine Band diatonic harmonica. In the 1990s, Billy acquired a piece of cypress wood from Muddy Waters’ cabin near Clarksdale, Mississippi, sent it by Greyhound bus to John in Boise. John built a couple of fabulous guitars from it. One of these Muddy Wood solid-bodies was featured on the cover of “Living Blues” magazine, in the hands of John Lee Hooker. I believe that’s the one now in the Delta Blues Museum in Clarksdale. In 1999, John and I collaborated on a project to use some of the remaining wood as combs on four Marine Bands. (The actual idea was Kim Field’s, although they were built without his knowledge; he received one of them as a surprise gift on his 49th birthday.) The obvious person to build the harps was Joe Filisko, who did so enthusiastically and expertly, signing each one. These four historic Muddy Wood Marine Bands, each in a separate key, are owned, respectively, by Billy Gibbons, John Bolin, Kim Field, and me. These harps have incredible tone and volume. Joe Filisko is a master.

I gave up on Hohners long ago. Lee Oskar (of WAR fame) has a nice line of harps, and many pros nowadays play Suzuki harps (my own favorites).

Whoa. Nice piece. Thanks!

FlashHarp® from Backyard Brand® is kind of like the “coin harp” you mention (except instead coins its 8GB USB drive stores memories, videos, etc.). I’d post a pic but your TOU prohibit that (‘cuz I make it). Maybe somebody else will. Here’s my own take on the instrument’s evolution: http://www.backyardbrand.com/1/post/2012/08/a-funny-thing-happened-to-the-harmonica-on-its-way-to-the-heart-of-the-american-sound.html

Great article, but I’d like to add that the person who actually convinced Hohner to improve their diatonic harmonicas is Steve Baker, an incredible player from Britain who has been living in Germany for ages. He’s the connecting force between customizers like Joe and Richard and the manfacturer. I don’t think we’d have superior product like the Marine Band Deluxe, Crossover or Thunderbird without his insistence.

Just Amazingly great article!

Great job!

Would off course loved to add The performance of Jimmy Z, playing in Eurythmics on the Nelson Mandela Concert in -88.

That one would fit the part (if not be the crown) of harmonica in POP industry I would say ;-)

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HhVqiu5lOXA

Great Article!

HarmonicaLessonsNYC.com

Thank you , very informative and interesting article !

Nice article. A little more on Lee Oskar’s innovations would have been good though!

Paul Cohen aka Komuso Tokugawa

HarpNinja – Your harmonica Mojo Dojo

Bringing the Boogie to the Bitstream

I found this article very interesting. Suck me in like a sponge. I fell for the harmonica bug in late 80’s, some still look at me weirdly. I’ve yet to try a Thunderbird but hope to. Hohner has definitely up their game with diatonics.

It`s great to read about these guys. Maybe I should submit a piece on the Harmonix wireless harps???? I`d send a pic but don`t know the attachment procedure.. Richard

loved this article,brilliant read

Interesting article with a large hole in it,as it only fleetingly mentions Lee Oskar and his harps.As those of us playing since the 70s remember it was in fact Lee who first offered a working,commercially available alternative to Hohner in 83′,offering alternative tunings,replaceable reed plates,repair kits and a nearly indestructible basic harmonica.It was Oskar who was the one that made Hohner get off their ass and move and to brush him off as you do seems downright disrespectful.His contribution was enormous and all he gets is a small sentence.Was this intentional?

I sat with Sonny Terry before he and Brownie played their gig at the Russell club in Hulme Manchester in the late seventies and he played Golden melodies at that time and back to front also which blew my mind at the time.I played him a bit of “crow jane blues” and he remarked kindly that I was “a good old boy” and that was enough for me.When they hit the stage it was fantastic and will always be my claim to fame.Ps in England the Marine Band was called the Echo Vamper and I still have a few of them and they are as airtight as the day I bought them but I did but some very ropey Marine Bands in the seventies and eighties.Great harps available today though so it was worth waiting for.Jim.Liverpool.

To Dave White.You are so right on Lee Oskar harps.I nearly had pups when I got hold of my first one.They are still good harps and unlike the old and maybe the new marine bands or echo vampers for that matter you can put them in your back pocket and sit down as many times as you like and not squash them.I know because I have spent most of my life sitting down in pubs.JimLiverpool.

Not one mention of Borrah Minevitch and his Harmonica Rascals? Great article though. I haven’t played in years myself. I think I’ll do the world a favor and keep it that way!

Very very nicely written, researched and presented. Best I’ve read on the subject.

Thanks for a good read on my favorite topic.

I missed mention of Dylan in the prominence of the instrument from the early 60s through late 70s. I see Charley Stevie Wonder, Lennon, Butterfield, McCoy, Lennon, Wonder, Jagger, Sebastian, Magic Dick, Neil Young…

Still I really enjoyed this piece, and though having played for over 20 years, learned a few things that will fuel my next practice session. Thanks Ben Marks!

Great memories of my own past (I started playing at the 1966 Phila. Folk Festival blues harp workshop with Paul Butterfield). But personally when Hohners became problematical I just switched to Lee Oskars and never looked back. I still have some I bought over 20 years ago. You might want to do an update or follow up on the other great harps that Hohner was an inspiration for.

The harmonica consists of 6 tremolo harmonicas fused together. The result is a massively expanded tonal range.

If you in the St Louis area and what to see over 3500 harmonicas give me a call I am in the book Harland Crain