When Caitlyn Jenner made her debut on the July 2015 cover of “Vanity Fair” in full old-Hollywood glamour mode, her highly styled appearance triggered discussion and debate: After all, not every woman has the money to, or even wants to, embody that particular ideal of feminine beauty, which involves elaborate foundation makeup to create shimmery highlights and contoured cheeks. Fifty years after the women’s lib movement railed against makeup, we’re still deeply conflicted about the stuff. Is it a tool for oppression—a way to force women to conform to certain standards meant to please or seduce men? Is makeup empowering women, especially trans women like Caitlyn, to express their identities? Or does the culture of makeup give women more work to do, by making them ashamed of the faces they wake up with?

“She encouraged women to be exceptional at a time when the world disparaged nonconformity and hated it for women.”

In the Victorian and Edwardian periods, respectable Western middle-class society condemned regular use of makeup, which was thought of as something only stage actors and prostitutes used. (Although some women probably dabbled in light makeup behind closed doors to fake the flawless bloom of youth.) In the 1910s, though, women in the suffrage movement wore bright red lipstick as an act of defiance. Helena Rubinstein—an early global female entrepreneur who began selling cold cream at her first beauty salon in Australia in 1902—jumped at this opportunity to create a mass market that never existed before: She championed makeup as a way for women to reinvent themselves and assert their individual personalities. For the flapper feminists of the 1910s and 1920s, makeup became a tool of liberation—both economic and sexual—and Rubinstein taught them how to apply it.

“Women were under such parochial constraints, including sartorial and domestic expectations,” explains Mason Klein, curator of the Jewish Museum in New York City, which presented the first-ever retrospective of the cosmetics magnate’s life and collections called, “Helena Rubinstein: Beauty Is Power,” this past winter. Currently, the Jewish Museum-organized show is on display at Boca Raton Museum of Art in Boca Raton, Florida, until July 12, 2015. “The middle class frowned terribly upon women who wore makeup. It was only actresses, prostitutes, and the very wealthy who could make themselves up. Rubinstein wanted to make beauty accessible to everyone.

Top: Cosmetics magnate Helena Rubinstein always projected a scientific image. (Via Girlboss) Above: A vintage Helena Rubinstein compact in the Jewish Museum exhibition. (Photo by Bradford Robotham)

“To her credit, she allowed women to learn about themselves,” Klein continues. “Putting on a face has a superficial meaning today, but back a hundred years, women didn’t have that right to be subjective about their image. They had to hew to one moral standard. She encouraged women to be exceptional at a time when the world disparaged nonconformity and hated it for women.”

Rubinstein believed every woman has the option to become beautiful. However, she never questioned the importance of beauty itself. “She had several mottos,” Michèle Fitoussi, the author of Helena Rubinstein: The Woman Who Invented Beauty, tells me via email from Paris. “The first one was ‘Beauty is power.’ The second one was ‘There are no ugly women, only lazy ones.’ Rubinstein thought that every woman could be beautiful and that their beauty was their best weapon for success—not to be a demimondaine [or a woman of loose morals], but to be independent and free.

“Obviously, it was—and it still is—easier to get a job if you are good-looking and well-dressed, rather than if you are ugly, have a bad complexion or wear old-fashioned clothes,” continues Fitoussi, who was an editor at French “Elle” magazine for 25 years. “When she first came to Australia, Rubinstein was witnessing the beginning of women’s employment. She understood very quickly how important getting the right look was and would be for women. She had this feeling that in this new century, women would have increasing importance and influence in the public sphere.”

Helena Rubinstein leads a class on how to apply makeup. (© Helena Rubinstein, Inc.)

Helena Rubinstein, who was only 4 feet 10 inches tall, was a master of self-reinvention herself. Born to a conservative family in Poland in December 1872, Chaja Rubinstein had a surprisingly modern point-of-view: While Rubinstein never considered herself a feminist, she never wanted to live under the thumb of a man. Growing up in an impoverished, provincial community in the Kazimierz district of Kraków, Poland, she dreamt of a much bigger life than becoming the demure housewife her Orthodox Jewish parents wanted her to be.

In fact, as soon as she struck out on her own, Rubinstein would try to obscure her humble origins, creating larger-than-life myths about herself—which is why the truth of her story is often difficult to parse out. According to Helena Rubinstein: The Woman Who Invented Beauty, Chaja, the first born of eight daughters, helped her housewife mother raise her sisters. Chaja’s favorite memories of childhood involved visiting her grandparents in the country, where their handyman, Stass, would create realistic dollhouse furniture. For the rest of her life, Rubinstein would be obsessed with miniature rooms.

The Jewish Museum show features a miniature room from Rubinstein’s dollhouse collection that depicts an early 20th-century Montmartre artist’s studio. (Tel Aviv Museum of Art, Israel)

“Who knows if it’s apocryphal or not, but she claimed that it was her grandfather’s gardener who first carved a little piece of furniture for her,” Klein says. “She and her successive seven sisters enjoyed collecting such things and making little dollhouses. She never stopped collecting.”

Even though they were poor, Chaja’s mother, Gitel Rubinstein, took great pride in teaching her girls how to groom themselves impeccably, brushing their hair 100 strokes and applying a special cream to their fair skin every night. Her mother claimed the cream had been developed by the Lykusky brothers, local chemists who shopped at their father’s general store, for the famed Polish actress Helena Modjeska.

Young Chaja’s formal education ended at age 16, as it did for most girls of her station. She never went to college, even though she was fond of hanging out on the Kraków University campus. She later claimed she studied medicine briefly but had to quit because she couldn’t stand the sight of blood. In reality, Rubinstein was doing the bookkeeping for her father, Hertzel, who didn’t have a mind for commerce. Although she saved him from financial ruin more than once, her family was not interested in her business acumen. They were more concerned about her prospects for marriage.

The Rubinsteins hadn’t managed to save up a dowry for Chaja, and according to custom, she would have to marry before her other sisters could be courted. To their chagrin, Chaja wasn’t willing to play along. She had no desire to be trapped as a bored housewife in Kraków and, by age 21, had turned down four suitors. When her parents told her a wealthy old widower had agreed to marry her without a dowry, she flat-out refused his offer, claiming she loved a young man named Stanislaw, a medical student she may have never actually met. Hertzel blew up at her, and Chaja made up her mind to move out. She first lived with her mother’s sisters, one in Kraków, and then another in glamorous Vienna—where she worked for her uncle’s fur shop and learned to speak German.

Thanks to encouraging letters from a cousin, Chaja, at age 24, decided to move to Australia and live with her uncles in a small country town called Coleraine in the state of Victoria, more than 200 miles from Melbourne. Her family agreed the move would be a good solution for their rebellious spinster and perhaps her last hope for marriage. Her mother sold jewelry to buy the boat ticket and gave her daughter 12 jars of her precious skin cream. On the ship’s passenger list, Chaja gave her name and age as Helena Juliet Rubinstein, 20. At the time, 1896, it was so unusual for a young woman to travel alone that many passengers wondered whether she was a prostitute and men showered her with attention, which she did not return.

Life wasn’t much better for Rubinstein in Coleraine, which she found to be a miserable, unglamorous sheep-herding community. Helena took English classes while she managed her uncle Bernard’s general store. She found herself arguing with Bernard while dodging the lecherous advances of her uncle Louis. But she had one glimmer of hope: The farmer’s wives—who had dry, tanned, damaged skin from working in the sun—coveted her fair, unblemished complexion.

An ad for Rubinstein’s Valaze beauty preparation from the 1910s. (© Helena Rubinstein, Inc.)

“Women of English ancestry—who had once had fair skin like she did—were amazed at her Victorian paleness and wanted to know how she maintained her skin,” Klein says. When she credited her mother’s skin cream, the women begged for a sample. Suddenly, she saw a path to freedom. Her cream was running out, so she wrote home to ask for the Lykusky recipe.

Helena worked her way toward Melbourne, working for a pharmacist and then as a governess, learning everything she could about chemistry and reading about botany and the beauty secrets of ancient societies. In her free time, she experimented with mixing plants and lanolin oil from sheep wool, attempting to re-create and perfect her mother’s magic skin cream. Finally, she developed a cream derived from the recipe she received from her mother—which supposedly included Carpathian pine bark, sesame, almond essence, spermaceti, and lanolin—and named it Valaze, which sounds like a Hungarian word for a “gift from heaven.”

“Her whole life, Helena had suffered a lot of poverty,” says her biographer Michèle Fitoussi. “She wanted to succeed and become rich. When she had this brilliant idea to produce her mother’s cream and sell it on a beauty parlor of her own, she left Coleraine and worked hard to make a little money as a nanny in a rich family. Then she went to Melbourne, worked as a waitress, and step by step, she opened her first beauty parlor at the age of 30, in 1902. She had little money so she bought some bamboo furniture for a few pounds, set up a little laboratory she called ‘her kitchen’ to make her cream, and sewed curtains from one of her dresses. Then she hand-painted the letters of her shop herself. And the clients began to come.”

Although hairdressers, massage parlors, and nail salons were abundant in turn-of-the-century Australia, Rubinstein’s skin-centric beauty parlor was something new, and an immediate hit. Through talking to women about their skin, she had deduced that there were three basic skin types—normal, oily, and dry—and three different kinds of white complexions—blond, brunet, and redhead—and each needed different types of skin care. At her salon, Rubinstein would give scientific-seeming classes about skin care wearing a lab coat. She advised her clients to stay out of the sun, and women would come to her begging for help with their freckles, blemishes, and scars.

A 1920s ad for Valaze Pasteurized Cream shows women enjoying outdoor sports like golf and tennis. (Via olfaktoria.pl)

Overwhelmed by the popularity of Valaze, Rubinstein put would-be suitors to work at her fledgling company and wrote to Dr. Jacob Lykusky, one of the brothers who provided her mother’s skin cream, asking him to come to Melbourne. After he arrived, Lykusky helped her reformulate her Valaze cream and develop a soap, an astringent, and a cleansing cream. But she wasn’t satisfied; she wanted to keep expanding her knowledge base and, in turn, her business.

“It was only actresses, prostitutes, and the very wealthy who could make themselves up. But Rubinstein wanted to make beauty accessible to everyone.”

Rubinstein took a trip to Europe to visit her family and research skin care in 1905. She was particularly enchanted by spas in Vienna with their hydrotherapy, body wraps, and chemical peels. In Paris, she took a class on hygiene from famous chemist Marcellin Berthelot, who discovered disinfecting with bleach in 1875. She consulted with dermatologists on techniques to reduce wrinkles.

She grew fascinated with therapies using massage rollers and electrical stimulation, as well as with how food could affect the body. She came away with electric body rollers, slimming tablets, and product formulas to fight acne and sun damage, as well as a beauty philosophy: Not only should her clients use her products, they also needed to exercise, practice proper breathing, and eat a low-fat low-toxin diet of mostly fruits, vegetables, and water.

“She professed that there are certain things that are good, and some that are terrible, for your skin and for your health,” Klein says. “She constantly tried to advise people, and she constantly learned. Her advertising tried to be as personal as possible. When she published instructional books and brochures with advice on the dangers of suntan and the necessity of good nutrition and exercise, she stressed self-knowledge and a way to find yourself in all of this, so it wouldn’t be superficial. It was all about realizing that if one were to find one’s own individualism, which was based on the notion of difference, you would learn something about yourself. At the time, it was pretty radical.”

Valaze Water Lily Novena face powder came in this hexagonal box, circa 1920s-’30s. (Via eBay)

While Rubinstein was a relentlessly hard worker, she spent no time socializing and, therefore, networking on behalf of her shop. But that would soon change. After she returned to Australia, a Polish-born American journalist, Edward William Titus, sought her out and began squiring her around Melbourne, taking her to theatre and fine-dining establishments. Taken by his intelligence and charm, she hired him to manage her company’s marketing and advertising.

With Titus’ help, in 1907, she opened her first franchise in Sydney, and a year later, another salon in Wellington, New Zealand. That same year, 1908, Rubinstein, at age 36, married Titus in London, where they had moved and were establishing a beauty salon, Maison de Beauté Valaze. It was Titus who encouraged her to go by “Madame,” and out on the town, they rubbed shoulders with Somerset Maugham, George Bernard Shaw, J.M. Barrie, and Virginia Woolf. Before long, the British elite, as well as popular stage actresses, flocked to and endorsed her parlor.

While spending time with actresses such as Kate Cutler, Lily Else, and Gabrielle Ray, who were based in London, and Fanny Ward and Edna May, who were on tour from America, Rubinstein got the radical idea to create a line of makeup for regular women. “She employed some actresses to advertise her Valaze cream, so it was easy to ask her new friends to teach her their art and their ways of using tinted face powders,” Fitoussi says. “She knew that such a change in ladies’ habits would be slow. But women, especially in high society, were becoming interested in makeup. Helena showed Margot Asquith, the prime minister’s wife and a regular client at her beauty parlor, how to use pigments. Asquith was one on the first English ladies who dared to be seen wearing makeup. This was a good publicity for the Maison de Beauté Valaze.”

Helena Rubinstein holds one of her masks from the Ivory Coast in 1934. (Photo by George Maillard Kesslere, courtesy of the Jewish Museum, via the Helena Rubinstein Foundation Archives, Fashion Institute of Technology, SUNY, Gladys Marcus Library, Special Collections)

Asquith invited Rubinstein to high-society parties, where she met eccentric redheaded Baroness Catherine “Flame” d’Erlanger, who began to take Rubinstein to antiques store and flea markets. D’Erlanger helped Rubinstein hone her interest in Baroque, Rococo, and Venetian furnishings and art within the realm of good taste. A friend of Titus’, painter and sculptor Jacob Epstein, took Rubinstein under his wing and piqued her interest in museum exhibitions, art history, and art criticism. While she may have been exposed to Aboriginal art in Australia, he encouraged her to appreciate the so-called “primitive art” from Africa, Latin America, and Oceania that influenced contemporary artists such as Matisse, Derain, and Vlaminck. Rubinstein cultivated an expertise about the sculptures of Congo, Mali, and Senegal, which Western artists such as Gris, Modigliani, and Picasso later made fashionable.

“She had several mottos. The first one was ‘Beauty is power.’ The second one was ‘There are no ugly women, only lazy ones.’”

“She was a great self-made art collector,” Fitoussi says. “She bought by instinct. And she had several connoisseurs teach her art and literature. The most important was Edward Titus, her first husband, who was a kind of Pygmalion. He introduced her to the art elite, in London, Paris, and New York. Helena was a brilliant student. She began to collect African art just before it was in fashion. She was influenced by Jacob Epstein, who asked her to buy some statuettes at Drouot for him, and when he couldn’t afford the price, she bought the pieces. He taught her everything he knew about primitive art, and soon, the student overtook the master. She liked unusual beauty.”

She became the first prominent European collector of African and Oceanic art, Klein explains. “Her salons mingled Western and non-Western art, and it that way, she democratized art, letting us look at African and Oceanic in the same way we look at classical art,” he says. “She was one of the first to help move it from its former ethnographic or primitive status to beautiful fine art. When all of her collections were auctioned off in ’66, her African and Oceanic art was so important that it changed the terrain of the field. Because she had so much, it was a study opportunity.”

This Helena Rubinstein compact in the shape of a frog, circa 1960s-’70s, was meant to be carried in the purse so a woman could easily refresh her fragrance. (Via eBay)

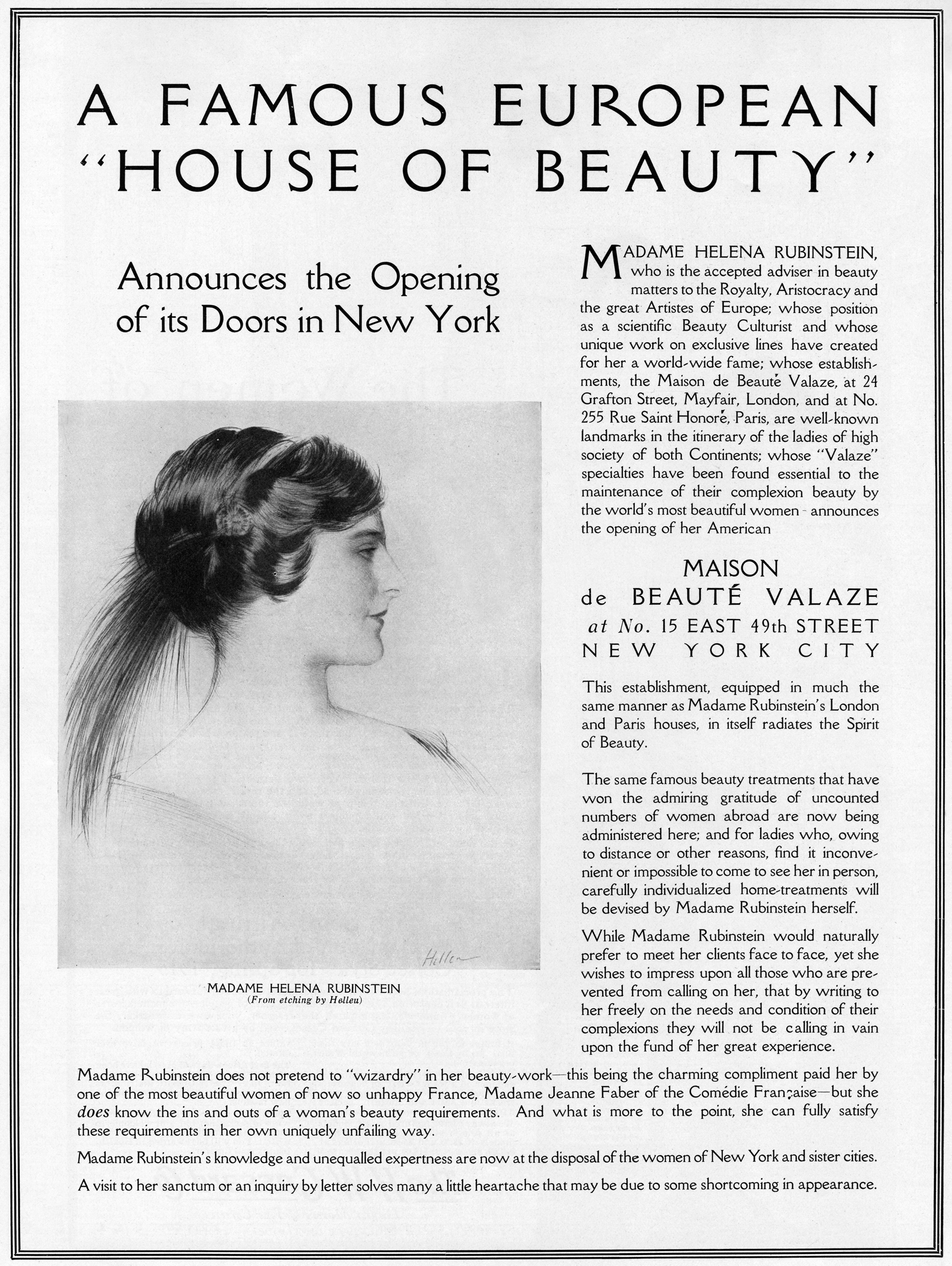

In turn-of-the-century London, Rubinstein also began to appreciate artwork that might be considered weird or ugly by conventional standards, she said, if “it is done with flair and a belief that it is right.” She disliked art she found sentimental or banal. She applied her interests in art to her philosophy on beauty, and as Fitoussi writes, Rubinstein believed “any face could be beautiful if it had character.” To capture her own highly unique face, she commissioned high-society artist Paul César Helleu to paint her portrait in 1908. This was the first work in a series of portraits of herself she collected; later portraits were done by Salvador Dalí, Marie Laurencin, Raoul Dufy, Christian Bérard, and dozens of others.

“She called her jewelry her ‘armor’ because it wasn’t easy working in a man’s world of business back in the early 20th century.”

At her well-appointed home in suburban London, Rubinstein developed at a taste for entertaining high society herself. She regularly traveled to Paris to attend art exhibitions—she never missed the Salon d’ Automne—and buy the latest fashions from couturiers. To console herself about her handsome husband’s philandering ways, she often bought herself extravagant pieces of jewelry as well. She made friends with groundbreaking fashion designer Paul Poiret, who is credited with freeing women from corsets. Women in London would marvel at the gorgeous, kimono-inspired dresses he’d make for her, giving Rubinstein a reputation as one of the most stylish women in the city. In 1909, she opened Maison de Beauté Valaze at a fashionable Paris address on Rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré, and in December of that year, she gave birth to her first son, Roy Valentine Titus.

While the British had been reluctant to embrace makeup, Parisian women were already wearing garish makeup by the time Rubinstein arrived. “When she opened her salon in Paris, women there not only wanted to look good, they also wanted to break taboos,” Fitoussi says. “They were different from the English ladies, who were only concerned about their delicate complexions. In Paris, wearing makeup had gradually become a right, but women used it too much. Madame, as people used to call Helena, decided to teach Parisian women moderation and to put a stop to what she described as a ‘massacre,’ by which she meant too much makeup.”

Fitoussi explains that Rubinstein’s company was growing so popular, she could no longer make her products by hand, so “she worked with the chemists of her first factory, opened in Saint-Cloud, France, in 1911, to produce makeup she liked, such as lighter textured foundation and delicate face powders.”

All the while, Rubinstein continued to refine her taste and expand her art collection. She became obsessed with a young unknown artist named Elie Nadelman. At the first gallery show of his work she attended, she bought all of his pieces, and as they became friends, she went on to showcase his work in her salons. (After his death, Nadelman became widely considered a pioneer of Modernism.) Watching the Ballet Russes perform in London in 1911, Rubinstein was mesmerized by the rich golds, magentas, oranges, yellows, and purples of the costumes and sets—and immediately went to her London salon and began to tear down the curtains. In a few days, she had remodeled her salon after Leon Bakst and Alexandre Benoit’s vibrant palette, which also influenced Poiret and her friend, interior designer Flame d’Erlanger.

Rubinstein gave birth to her second son, Horace Gustave Titus, in May 1912 (named after her still-estranged father, as Horace is the English version of Hertzel). That same year, she moved her whole family to Paris, where she was also reborn, her Madame image solidified: From then on, Rubinstein always wore her dark hair in a tight chignon, very little makeup except for red lipstick, and bold jewelry to counter her short stature.

“She wrote that had she been more of a statuesque or taller woman, she wouldn’t have had to wear the kind of jewelry that she chose for herself, which was very armor-like,” Klein says. “She called it her ‘armor,’ and she needed that protection because it wasn’t easy for a woman working in a man’s world of business back in the early 20th century. She wore necklaces and cuffs and really defining pieces, nothing demure. She wore lots of pearls, but she also creatively mixed costume jewelry with precious jewels in an incredibly effective manner.”

Rubinstein, photographed by Nickolas Muray in 1924, wears a 1923 Paul Poiret dress. (Courtesy of the Jewish Museum, courtesy of George Eastman House, International Museum of Photography and Film. © Nickolas Muray Photo Archives)

Madame was never seen without silk stockings, manicured nails, and a matching bag and shoes. At a party in honor of Ballets Russes, famed socialite Misia Sert took Rubinstein under her wing and introduced her to the customs of Parisian high society, where she met writers Marcel Proust and Colette, the latter of which became her regular client.

“Rubinstein wore little makeup, except her trademark lipstick, and dyed her white hair jet black,” Fitoussi says. “She always wanted to be impressive. In fact, she was. Her personality was strong, and she reinforced it by wearing sublime clothes and big jewels.”

Rubinstein remodeled her Parisian parlor in fashionable Art Nouveau style and hired a Swedish masseuse to help women shed unwanted pounds and stimulate their genitals. Because society dismissed the idea of female sexuality, at the time, it was simply considered good health care for a doctor or massage therapist wielding an electric vibrator to treat a woman to an orgasm.

After the outbreak of World War I in 1914, Rubinstein and Titus realized that Paris would soon be under siege. Because Titus was an American citizen, his whole family had U.S. citizenship. In October of that year, Rubinstein left Titus in charge of packing the house and went ahead to New York to find an apartment and set up a salon there.

A 1915 “Vogue” advertisement announces Rubinstein’s inaugural beauty salon in New York. The ad features a portrait of Rubinstein by Paul César Helleu. Click on the image to see a larger version. (Courtesy of the Jewish Museum)

Rubinstein was dismayed by the appearance of American women, who were at least a decade behind their European counterparts, fashion-wise. They still emulated Charles Dana Gibson’s fictional Gibson Girl, who narrowed her waist in a tight corset. They would only wear light powder and blush to lunch, but not dinner, believing they could attain beauty through a healthy lifestyle and positive thinking. However, the women’s suffrage movement had been going strong in America for years, and early feminists like Lucretia Mott, Elizabeth Cady, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, and Inez Milholland were holding meetings and discussing sexuality, contraception, and abortion. The May 6, 1912, Suffrage Parade in New York drew 20,000 women and 500 men, dressed in white. Many of the women shocked onlookers wearing lipstick, “a mark of sex and sin,” according to Edward Bok of the “Ladies Home Journal.”

“When Rubinstein moved to the United States in 1915, she took advantage of the fortuitous zeitgeist happening in New York,” Klein says. “She arrived in the wake of two modernist events, the tsunami of Modern art in 1913 that was at the Armory Show art fair, and the suffrage movement where tens of thousands of women, some of whom were wearing lip rouge as a badge of honor, paraded for their voice.

“Today, we’re still struggling to have equal rights,” he says. “For men at the turn of the century, their moral compass was not apparent in how they looked. It was such a double standard; women who would be creative and flirt with any kind of image were judged. Too often people don’t appreciate the early feminist struggles and how it’s gone full circle in terms of makeup.”

This 1940s photo shows face-mask treatments taking place in a Helena Rubinstein salon. (Via Vintage Everyday)

Fortunately for Rubinstein, the demand for women’s rights opened up a new American market for products advertised toward women, from Pond’s Cold Cream to Jell-O to cars. Interest in beauty in the 1890s had led to the development of skin peeling, nose jobs, and facelifts. By the time Rubinstein arrived, there were already 26,000 hair salons, 25,000 manicure salons, and 30,000 massage and skin-care parlors in the United States. In New York, the Risers Manicure parlor offered every known beauty therapy under the sun including electrical treatments and hair removal. Madame C.J. Walker had become America’s first self-made female millionaire with her hair products for African American women. In the late 1800s, another female entrepreneur, Harriet Hubbard Ayer, began to manufacture a popular skin cream, but in 1883, she lost the company when her main financial backer, a man, had her committed to an asylum.

Six years before Rubinstein landed in America, her biggest competitor was setting up shop. In 1909, Florence Nightingale Graham opened a cosmetics salon on Fifth Avenue, and in 1910, she revamped the shop and changed her name to Elizabeth Arden. She worked with a chemist to develop a face cream called Amoretta, packaged in elegant pink and gold jars, her favorite colors. Like Rubinstein, Arden came from humble roots but projected a more upper-crust past than she actually had. However, Arden telegraphed a conventional, WASPy patrician elegance that involved horses, golf, and country clubs, whereas Rubinstein wanted to come across as an exotic woman of the world with cutting-edge style.

“Rubinstein’s rivalry with Arden was war,” Fitoussi says. “They really hated each other. Rubinstein used to say: ‘We’ve never met,’ although they were both invited to attend the same parties and the same exhibitions in New York. Both were aware of what the other one was creating and what kind of products she was working on. Both used to spy and copy her rival. Arden hired a manager that Rubinstein fired, and Rubinstein hired Arden’s husband when they split.

“Rubinstein was a self-made woman, as Arden was, but she never pretended to be from patrician descent like Arden, who was raising horses in her country house and being a real snob,” she continues. “Rubinstein liked to talk to every woman who bought her creams, rich or poor, including the sales assistants and the secretaries. She wanted to know what they felt and what they needed. She first tested her new products on them, and she was really interested on their remarks and critiques. Eventually, she had several lines—some expensive for the beauty parlors and department stores, and others that were cheaper for the drugstores.”

A 1949 French advertisement for complexion powder and rouge drawn by Bernard Villemot. (Courtesy of the Jewish Museum, © 2014 Artist Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris)

Helena Rubinstein opened her first salon in New York City at 15 East 49th Street because her status as a Jew prevented her from renting a shop on Fifth Avenue. With the help of Austrian-born interior designer Paul T. Frankl, she created an environment that felt like a “chic bourgeois” dwelling that combined her avant-garde inclinations with the traditional mahogany and rosewood furniture that appealed to the rarified tastes of American elite. Rubinstein carefully constructed her image as a well-to-do, sophisticated European, and told the press her father was Russian and her mother was Viennese.

“Her first husband helped her develop an understanding of the beauty salon in the tradition of the literary salon, where progressive ideas would be discussed in a domestic setting under the aegis of a charming hostess,” Klein says. “This allowed her to create an environment in which you could consummately deal with all of these issues, such as decoration, beauty, fashion, and art.”

When Titus arrived with the children, the couple moved to a huge apartment in Manhattan and also bought a Tudor mansion in Greenwich, Connecticut, where her sons would be raised by a personal tutor and cadre of nannies. Rubinstein kept busy innovating: In 1915, the warm summer inspired her to develop creams to protect the skin from the sun’s rays. She recast her Valaze cream as a skin-cell regenerator. Arden installed exercise rooms in her salons, and Rubinstein jumped on the idea. Madame always projected a scientific image, boasting that she had her products tested for toxicity.

Saleswomen in uniforms line a Helena Rubinstein makeup counter. (© Helena Rubinstein, Inc.)

Thanks to Titus, she socialized with bohos in Greenwich Village, including Paris-based artists waiting out the war, such as Marcel Duchamp, Henri Matisse, and Francis Picabia. The couple hosted dinner parties in their Manhattan apartment, and Rubinstein was always sure to invite a few journalists, who were certain to report about her husband’s literati friends: Eugene O’Neill, Man Ray, Leo Stein, and e.e. cummings. The pair maintained a chic, unified image, but privately, Rubinstein regularly battled with her husband over his infidelity, while he accused her of putting her business ahead of her family.

Big-city department stores, small-town beauty parlors, and community drugstores around the United States often wrote Rubinstein, begging to stock her products. In 1917, Rubinstein made the difficult decision to make her cosmetics available to the masses. She struggled, though, with the fear her brand would lose its prestige or that without receiving a consultation, women would use her creams improperly. She decided to tour the country to visit each retailer and speak to its cosmetics department about her beauty philosophy. Back in New York City, she set up a school of beauty for people who wanted to sell her products. She encouraged business owners around the country to pay from $250 to $500 to send their staff to a six-month training session at her school, and then she provided them branded uniforms and displays, a brilliant marketing strategy.

Theda Bara in the 1917 silent film “Cleopatra.”

Because cinema was tremendously popular in the United States, Rubinstein hired silent film stars to promote her brand. Sex symbol Theda Bara asked Madame to make her up in a way that drew attention to her eyes on camera. Then Rubinstein introduced a makeup line called Vamp, inspired by Bara’s vampire character in the hit 1915 silent film, “A Fool There Was,” which established “vamp” as slang for a sexually predatory woman.

“Bara had beautiful, big eyes, but she wanted to enhance her look,” Fitoussi says. “She came to the New York beauty parlor, asking Madame to help her. The result was dramatic, the media was impressed, and women wanted to imitate Bara’s new makeup.”

After the war ended in 1918, Rubinstein returned to Paris to reopen her salon. Women, who had performed tasks during the war that were previously considered men’s domain, relished their newfound independence. So-called flappers smoked, drove cars, and went out dancing in scandalously short skirts that proclaimed their sexuality. They rejected the confinement of corsets and embraced androgyny, cutting their hair short. Mascara, lipstick, and rouge were seen as tools of liberation. Rubinstein, Arden, and French perfumer Guerlain offered reticule-style handbags to carry makeup, and then gold-plated and bejeweled compacts meant to look like jewelry. Primping in public was an act of insubordination.

But this sense of sexual freedom came at a cost: The old hourglass body ideal was replaced with a slender boyish figure, and the rise of fashion photography presented an unattainable body image. Women were showing more skin and enjoying outdoor sports like swimming, tennis, golf, and bicycling. Because legs were exposed and stomachs were no longer held in by corsets, women went to extremes to lose their spare tires and thigh cellulite—taking weight loss pills, getting massages, visiting dietitians, and even getting surgery. Cocaine became a popular drug because it suppressed the appetite and gave women the energy to do the Charleston all night.

An enameled Helena Rubinstein compact, circa 1930s. (Via Tangerine Boutique)

Rubinstein had predicted this body obsession, and she, in fact, fed this quixotic pursuit for perfection. At her salons, consultants offered skin-care advice and told women they could reshape their stomachs, thighs, and arms through massages, exercise, and proper diet. Rubinstein insisted that beauty was vital to all women, and one had to suffer to attain it. Her ads struck fear and shame into the hearts of women: Even those who thought they were happily married could lose their husbands’ affection if they got “lazy” about their appearances. In 1923, she introduced a line of “reducing preparations,” or body-slimming creams. Of course, she also endorsed cosmetic surgery. Even though Rubinstein had been an early advocate of protecting one’s skin from the sun, after Coco Chanel made suntans fashionable, Rubinstein installed sun lamps in her salons in 1932 and offered water-resistant self-tanning creams in 1936.

“In the 1910s and 1920s, Poiret and Chanel gave up the corset to free women’s bodies,” Fitoussi says. “In addition to skin care and makeup, Rubinstein supported good health, massages, thermal therapies, sports, gym exercises, and diets. She wanted to build a new kind of woman by improving beauty. In the history of women, independence is not only a question of money or power but of physical freedom as well.”

Beauty was becoming a major industry in the United States and Europe as postwar consumerism exploded. In 1919, according to Fitoussi’s book, ads for beauty products accounted for 20 percent of magazine pages, and cosmetics were the second biggest advertisers for “Town and Country,” “Harper’s Bazaar,” and “Vogue.” The Miss America beauty pageant debuted in 1921. Mass manufacturing of cosmetics made them more readily available to middle-class women. Hundreds of creams, face powders, and lipsticks flooded the market (Rubinstein’s Saint-Cloud and Long Island factories made more than 70 product lines), and the average American woman spent $300 a year on cosmetics. By the late 1920s, women in the U.S. were putting down a total of $700 million a year buying beauty products and visiting beauty parlors.

Helena Rubinstein reads by the fluorescent lighting that suffuses the head and foot of her Lucite bed, which was designed by Ladislas Medgyes in the late 1930s. (Photo by Herbert Gehr/Time Life/Getty Images, courtesy of the Jewish Museum)

In 1928, Rubinstein moved her salon to Manhattan, at 8 East 57th Street, Fitoussi writes. At that point, Madame had 3,000 employees, as well as 5,000 approved selling agents working for department stores, beauty salons, and drugstores. Her face looked much younger than her 56 years, but she had put on weight. She insisted she was simply too busy to follow her own diet and exercise advice. Most nights she only slept five hours, but as she aged, she took cruise-ship vacations that allowed her to catch up on sleep. From the outside, her life looked pretty fabulous. As a host and guest, she socialized with D.H. Lawrence and his wife, Frieda, William Faulkner, Ernest Hemingway, James Joyce, Coco Chanel, Christian Dior, Gertrude Stein, and Marc Chagall.

“Rubinstein liked to talk to every woman who bought her creams, rich or poor.”

She indulged in collecting of all types: She bought art from innovators at the forefront of the Impressionism, Dadaism, Surrealism, Fauvism, Cubism, and Modernism, including Degas, Monet, Renoir, Brancusi, Braque, Miró, Picasso, and Modigliani. She accumulated miniature rooms and dollhouse furnishings, opaline glass, china and silverware, and extravagant furniture to adorn her homes in New York, Connecticut, and France in stylishly eclectic and avant-garde style. Of course, she amassed an impressive collection of jewelry, both fine and costume. She was one of Surrealist designer Elsa Schiaparelli’s first clients, and her couture wardrobe included pieces by Poiret, Coco Chanel, Caroline Reboux, Edward Molyneux, Jeanne Lanvin, and Lucien Lelong. Later, she also became a regular client of Madeleine Vionnet, Cristóbal Balenciaga, and Yves Saint Laurent. To accessorize her fabulous clothes, she bought hats, furs, belts, and shoes made to measure for her tiny feet.

“Rubinstein is a fantasist, so she loved the Surrealism that Schiaparelli adorned us with in the ’30s,” Klein says. “One of the most famous pieces within the Rubinstein retrospective is this circus bolero jacket that has dancing elephants and even trapeze artists swinging in sequential movement on top of the jacket and glass beads embroidered in. So not only does it create a feeling of movement, but it also replicates the strobic light that is seen in the circus. She and Schiaparelli were mutual admirers.”

The interior of Helena Rubinstein’s beauty salon at 715 Fifth Avenue, New York, in the early 1940s. (Via American Past)

On the business front, Rubinstein faced competition from French companies such as René Cory, Guerlain, Roger & Gallet, and Bourjois, as well as the major American brand Pond’s and small upstarts like Maybelline, Noxzema, and Max Factor. Businessmen noticed that the beauty industry—which had been created by women for women—had the potential to fatten their bank accounts. Male-led companies began to acquire cosmetics brands started by female entrepreneurs.

“Just as the Modern artist had the liberty to paint grass red or the sky yellow, the new modern woman determined for herself how she wanted to be seen.”

So it only made sense that the Lehman Brothers had their eyes set on the Helena Rubinstein brand, which had $2 million in gross earnings in 1927, Fitoussi writes. They offered Madame $7.3 million dollars, which would be the equivalent of $90 million in today’s dollars. She agreed to sell 75 percent of her shares in her American business, keeping her factories and the European and Australian branches. When the Lehman brothers put the company on the market in 1928, women bought 80 percent of the shares available. Right away, the Lehmans, not understanding the beauty industry, saturated the market and put the products in grocery stores, tarnishing the Rubinstein brand image, which outraged Madame. She sent threatening letters to the Lehmans and wrote every single female shareholder. After the stock market crash on October 24, 1929, Rubinstein managed to buy the company back for mere $1.5 million, netting a total of $5.8 million, which made her the wealthiest woman in the United States at the onset of the Depression.

Rubinstein’s business did well in the poor economy, because women who couldn’t afford a new dress would console themselves with a tube of lipstick. But her personal life was not faring so well. When Rubinstein’s parents died in 1931, it sent her into a tailspin of regret for not spending more time with them. Her husband, who had operated a rare-books store, a literary magazine, and a modernist publishing company on her dime, blamed her busy life for his cheating. Fed up, she finally filed for divorce in 1932, which was finalized in 1938. Her sons resented her, particularly for spending so much time with her niece, Mala, whom Madame had selected as her potential successor. Despite feeling the despair of her losses, Rubinstein soldiered forward in her business, coming up with product ideas based on women’s physical insecurities, such as anti-aging creams.

A 1943 Helena Rubinstein ad implies that a woman who forgoes her beauty routine may face infidelity. (Via Vintage Ad Browser)

To make matters worse, a 1930 piece in “Fortune” magazine all but declared Elizabeth Arden the winner in the beauty war. Using coded anti-Semitic language to describe Madame as “swarthy” and “buxom,” the author wrote that Helena Rubinstein’s salon was now outdated whereas Arden’s parlors appealed to elite women of good taste. When Rubinstein passed Arden’s elegant Fifth Avenue salon, she glowered and decided to finally buy her own building on Fifth Avenue.

When it opened 1937, Rubinstein’s new flagship 715 Fifth Avenue salon, decorated by Ladislas Medgyes and Martine Kane, was heralded as an achievement of Modern architecture and interior design. The walls were covered in metallic blue wallpaper and decked with paintings by Giorgio de Chirico, sketches by Modigliani, and murals by Peter Pallavicini. Sculptures by Nadelman and Malvina Hoffman were displayed on furniture by Jean-Michel Frank and carpets by Joan Miró.

A woman applies makeup at Helena Rubinstein’s Fifth Avenue salon. (By Nina Leen/Life Magazine, via Glamour Daze)

“She endorsed and created environments that were as changeable and creative as the cosmetic self-portrait that she encouraged everyone to consider for themselves,” Klein says. “She wanted to encourage women to determine what their aesthetics were, what their instinctual colors were, and what they liked. She made a correspondence between makeup as a metaphor for the mysterious patina of Modern art she had in her salon. Just as the Modern artist had the liberty to paint grass red or the sky yellow, the new modern woman determined for herself how she wanted to be seen.”

Rubinstein’s collection of miniature rooms was also displayed prominently in the new salon, which had a second-floor library featuring rare beauty books on beauty. “For years, she had a whole series of historically perfect handmade dollhouse rooms, in an encyclopedic range of decoration and design, installed in a museum-quality exhibition in her flagship shop on Fifth Avenue,” Klein explains.

A 1961 ad for Helena Rubinstein lipstick from “Australian Women’s Weekly.” (Via Vivat Vintage on Tumblr)

On Fifth Avenue, Madame introduced her “Day of Beauty” package, a full day of consultation and makeover with doctors, physical therapists, dietitians, masseurs, hair stylists, makeup pros, and manicurists, which was priced between $35 and $150. Women arrived at 8 in the morning for a full assessment, including their height and weight, eating habits, beauty routine, and medical history. The consultants would then draw up a plan for their day. A client’s morning including “facial gymnastics,” followed by a face massage, an electrical treatment to reduce cellulite, a shower of skin-firming oil, and time under the tanning lamps. Lunch included a low-calorie plate of grilled fish, vegetables, and fruit. Then, the client would be treated to a facial, a scalp massage, a stylish haircut, a manicure and pedicure, and a makeup lesson.

“She was and she remains one of the most incredible self-made businesswomen of the two last centuries. There are very few like her.”

“She tried to personalize what a salon could be,” Klein says. “She had an ideology that stressed individualism, at a time that really discouraged nonconformity. Your pores were analyzed. You’d learn comportment, how to walk, and dexterity. You learned the importance of nutrition and exercise. Rubinstein tried to have a scientific approach because, in those days, you had to appear as up-to-date with science as possible. She often used the analogy of a garden, when it came to maintaining one’s self on a regular basis. Her salons offered sun-lamp treatments on beds of sand, while you had drinks served to you. It was a rather thorough day of indulgence.”

This day of self-care for women was a smashing success, but Rubinstein was facing a new contender on the cosmetics market: Charles Revson, who launched a line of long-lasting nail polish called Revlon in the mid-1930s. Max Factor and Germaine Monteil were also making their mark, but neither scared Rubinstein and Arden as much as Revson, whom Madame dismissively referred to as “that nail man.”

A 1935 Helena Rubinstein pamphlet, “Your Cosmetic Portrait.” (Photo by Bradford Robotham, courtesy of the Jewish Museum)

Still, life was going well for Madame. In 1935, she met 40-year-old Russian prince Artchil Gourielli-Tchkonia, who fell in love with her and married her in 1938, just months after her divorce from Titus. Thanks to the chemists at her laboratory in Vienna, she was able to debut the world’s first waterproof mascara at the 1939 New York World’s Fair, where water ballerinas wore it while performing in the Aquacade. When it hit the consumer market in 1940, it was a smash success.

In the late 1930s, Rubinstein was also nervously watching Hitler’s rise to power and working to get her family out of Poland. She’d already hired most of her sisters and some nieces and nephews to work for her around the globe. But some of her family refused to leave their home country, which was invaded by Nazi Germany in 1939.

During World War II, Rubinstein provided the U.S. government moisturizers for the soldiers serving in the North African deserts and raised money for the Red Cross. To relieve her stress about the war, she took a cruise tour of Latin America, where she made friends with Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo and became obsessed with Mexican art. She decided to open salons in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, and Buenos Aires, Argentina. She also opened the first-ever boutique selling beauty products for men, House of Gourielli in New York City, named after her husband.

Tony Curtis became a regular client of the House of Gourielli beauty salon for men. (© Helena Rubinstein, Inc.)

To her great dismay, her sister Regina Kolin and her sister’s husband Mozsejz were slaughtered in the Auschwitz concentration camp in 1942. Several of Rubinstein’s uncles, aunts, and cousins died at the hands of Nazis, too, and the Kazimierz district she grew up in was completely ravaged. When she returned to France after the war ended in 1945, she found her luxurious art-filled Paris apartment ransacked and her Saint-Cloud factory smashed up. The Germans had stolen her proprietary cosmetic formulas and had operated her Paris salon without her permission until they ran out of product. Her salon in London, meanwhile, had been bombed. Looking forward, 72-year-old Rubinstein determinedly built chic new salons in Paris and London.

“When I first saw Pierre Bergé, co-founder of the Yves Saint Laurent couture house, he told me that when he was in his 20s, in the 1950s, he often used to go to Bernard Buffet’s studio, which was close to Helena Rubinstein Beauty Parlor Rue du Faubourg St Honoré,” Fitoussi says. “He noticed a Brancusi sculpture in the window. He was stunned. He told me that he has never imagined that one could put a piece of art in a beauty parlor window. Years later, remembering Madame’s beauty parlor, when he bought his first couture shop with Yves St Laurent in Faubourg St Honoré, he put a pair of Jean Dunand vases in the window.”

In America, the postwar economy focused on women as consumers. Forced to give up their jobs, stuck in housewife roles, and isolated in new suburbs, women were encouraged to look as feminine as possible and to comfort themselves with spending. While Rubinstein and Arden were still spying on each other and stealing each other’s ideas, they had other contenders to deal with who were entering the market that became known as “The Pink Jungle,” which put more and more pressure on women to live up to a flawless, ladylike ideal.

A 1945 Helena Rubinstein ad explains her “Color-Spectograph” approach to makeup. Click on the image to see a larger version. (Via Vintage Ad Browser)

Revlon products were low quality, but their names and marketing tapped into the emerging youth culture. Nail polish came in Pink Coconut, Frosted Champagne Taffy, and Pineapple Yum Yum. Clever Revlon ad campaigns drew women in: When the company debuted the Fire & Ice lip and nail color in 1952, a two-page ad featuring a model in a sexy skintight dress asked, “Are you made for Fire & Ice? Have you ever danced with your shoes off? Do you secretly hope the next man you meet will be a psychiatrist? If tourist flights were running, would you take a trip to Mars?” After that ad, the value of Revlon’s shares skyrocketed.

“The ‘nail man’ as she called him, Charles Revson—with the birth of TV and a new kind of bold advertising where sex was exploited—blew Rubinstein and Arden out of the water in terms of advertising, hiring the mad men of Madison Avenue,” Klein says. “They came from another era. Where Arden relied on packaging, Rubinstein kept on trying to develop new products and to publicize herself in every which way, because she was one of the most famous women in the world.”

Another threat to Rubinstein and Arden’s dominance came from another female entrepreneur, Estée Lauder—who also made up stories to obscure her poor American Jewish past as Josephine Esther Mentzer. Lauder found success opening a small family company in 1946 that only sold two face creams, a cleansing oil, and skin lotion. Her new marketing scheme, which was to give customers free samples with every purchase, made her a serious rival in the beauty industry.

A 1948 ad promotes Rubinstein’s “5-Day Wonder School.” Click on the image to see a larger version. (Via Vintage Ad Browser)

Tragedy struck Rubinstein’s life in the mid-’50s. Her much-younger husband died of a heart attack in 1955, and her 46-year-old son, Horace, was killed in a car crash in 1958. These losses devastated her, rending Madame unable to get out of bed for weeks at a time. But even though she was in her 80s, she managed to recover from heartbreak by focusing on her company and pushing forward.

By then, the obsession with keeping up appearances made makeup a must-have, as opposed to a tool of liberation. The American beauty industry was grossing $4 billion a year, and Helena Rubinstein, Inc., was grossing $22 million internationally, with 26,000 employees. Rubinstein moved her flagship salon to an even larger seven-story building at 655 Fifth Avenue. Madame expanded her “Day of Beauty” to a five-day beauty program, where she gave self-care lessons to women in the evenings and on weekends. In interviews, she insisted a woman could improve herself “with just two creams and 10 minutes of her time each day.” Smoky eyes inspired by Hollywood starlets were the look of the day, and so when Rubinstein introduced Mascara-Matic in 1958—the first mascara that stayed liquid and didn’t require women spit in the tube—it was a resounding hit.

Rubinstein had always been an authoritarian boss, prone to fits of temper and forgetfulness, and these traits only intensified as she aged. She manipulated her family with her money and pitted employees against each other just to relish the ensuing drama. She could be hard and stingy, particularly when it came to developing new products, but she had moments of tenderness and extreme generosity with family, friends, and employees.

At first, Madame objected to advertising on television, but changed her mind when she saw that Revlon’s sales were outpacing hers, thanks to Revson’s sponsorship of “The $64,000 Question.” In 1958, she sponsored a popular show reuniting variety hosts Imogene Coca and Sid Caesar. Before the show’s opening credits, a Helena Rubinstein commercial featured Madame herself in an elaborate chair, wearing pearls and a Dior dress trimmed with sable. In it, she says with a thick accent, “I’m Helena Rubinstein. Give me just 10 minutes of your time, and I’ll make you look 10 years younger.” The public loved it, and it turned her into a national celebrity. After that, she brilliantly placed deodorant commercials during televised wrestling matches.

Mascara-Matic, introduced in 1958, was a major innovation. (Via Glamour Daze)

By the time she was 90 years old in 1962, Rubinstein’s health was in a sharp decline, partially due to diabetes, but she still insisted on micro-managing her company, working from her bed most mornings. She died alone in 1965, after a heart attack and embolism, but her funeral was an A-list event. According to Fitoussi, at the time, her products were made in 14 factories and sold in 30 countries around the world. Helena Rubinstein, Inc., had a workforce of 32,000, and her personal net worth included $100 million in investments, property, art, jewelry, furniture, and money in bank accounts.

“Throughout her life, she kept on expanding our notion of what and who could be defined as beautiful, so she was very radical,” Klein says. “That’s one of her most important legacies, apart from her eclectic personal style and all of her sundry collections, all of which served to level a snobbish aesthetic taste that was arguably what Arden was doing, and to redefine what could beauty be.”

After Rubinstein died, the second women’s liberation movement grew in strength and pushed back against the idea that beauty should be important at all. Wearing makeup had once been an act of independence for young feminists, but by the late 1960s, it was the social standard upholding an old-fashioned version of womanhood that, to feminists, was starting to feel confining and controlling. The cosmetics industry was another corporate behemoth, selling an image that required women focus on their physical appearances, instead of their minds or their ambitions.

Apple Blossom was a popular Helena Rubinstein scent, available in perfume, powders, and other products. (Via eBay)

When Madame’s heirs sold the Helena Rubinstein brand to Colgate-Palmolive in 1973 for $143 million, the new owner couldn’t keep the magic alive. The corporation sold the brand in 1980 to a small cosmetics company, Albi Enterprises, who also failed to restore Helena Rubinstein products to their former place of esteem. But when L’Oreal bought the brand in 1988, the cosmetics juggernaut successfully revived the business, and sales in 30 countries, mostly in Europe and Asia, have been flourishing since.

“A lot of people forgot about Helena Rubinstein for years,” Fitoussi says. “But she was and she remains one of the most incredible self-made businesswomen of the two last centuries. There are very few like her.”

While makeup never went away in the past 50 years, it did become the subject of continuous heated debates. Today, Rubinstein’s legacy is widely felt, as women still spend fortunes trying to achieve unrealistic body ideals and keep their faces young and flawless. Makeup is big business, and even considered by some to be a rite of passage into womanhood. But has this obsession with beauty harmed or helped women in the long run?

“It depends on the balance and where you put the cursor,” Fitoussi says. “When women are not allowed to wear makeup, like in the United States in the 19th century or in Afghanistan under the Taliban, it’s against their liberty to act. Personally, I prefer to put on too much makeup and look like a whore than be deprived of doing what I want.”

Helena Rubinstein in front of a montage of some of the many portraits she commissioned throughout her life. (From the Helena Rubinstein Foundation Archives, Fashion Institute of Technology, SUNY, Gladys Marcus Library, Special Collections)

(“Helena Rubinstein: Beauty Is Power,” is on display at the Boca Raton Museum of Art, 501 Plaza Real, Boca Raton, Florida, through July 12, 2015. To learn more about Helena Rubinstein, pick up Michèle Fitoussi’s book, “Helena Rubinstein: The Woman Who Invented Beauty.” If you buy something through a link in this article, Collectors Weekly may get a share of the sale. Learn more.)

'The Great Gatsby' Still Gets Flappers Wrong

'The Great Gatsby' Still Gets Flappers Wrong

Bizarro Beauty Products, from 1889 to Now

Bizarro Beauty Products, from 1889 to Now 'The Great Gatsby' Still Gets Flappers Wrong

'The Great Gatsby' Still Gets Flappers Wrong Selling Shame: 40 Outrageous Vintage Ads Any Woman Would Find Offensive

Selling Shame: 40 Outrageous Vintage Ads Any Woman Would Find Offensive CompactsIn the 1920s, la garçonne, or the young flapper woman of the Art Deco era, …

CompactsIn the 1920s, la garçonne, or the young flapper woman of the Art Deco era, … AdvertisingFrom colorful Victorian trade cards of the 1870s to the Super Bowl commerci…

AdvertisingFrom colorful Victorian trade cards of the 1870s to the Super Bowl commerci… Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fascinating!

Brilliant, as always, Lisa. Thank you.

What an incredible piece. Thank you!

the problem with empowerment through makeup is that women feel disempowered without it. They refuse to leave their homes in extreme cases. Makeup has turned into a crutch. Women demand it from other women and judge them accordingly. Makeup is essentially a costume, a lie. Eventually the costume comes off. Plastic surgery is makeup even more exaggerated. Famously, a Chinese man successfully sued his wife for divorce because of her undisclosed, numerous plastic surgeries and heavy makeup which misled the man into thinking she was made of better genetic material. Doctors miss important health markers on sick women because they are made up to look well. It’s a double sided sword that works against women as much as for them. Many a man has woken up to find themselves with a stranger who has washed their makeup off. Many women are so over made up that they belong in a Japanese theater or a drag queen show. Makeup does make women more attractive and that attention is often unwanted. Makeup can make you look like professional sex worker. All in all it’s Pandora’s box. Once women have drunk from the well of deception and unearned power they rarely stop drinking. But they are living a lie and that lie tends to become more and more grotesque as they age.

What a fantastic article! Love it! Thank you Collector’s Weekly. – Jenn The Vintage Net

I am trying to locate pictures of Helena Rubinstein’s Salvador Daii room. I was there in the 1950’s and recall pictures of faces starting on the ceiling and coming down the wall. It was a fabulous room

Pax…you’re being overly dramatic. Makeup isn’t a “lie”, women don’t actually expect people to believe that they have naturally gold eyelids or red lips. If you’re stupid enough to believe that then you shouldn’t be allowed to date.

Makeup is a form of self-expression, much like fashion is. For some women, walking out the house without makeup would be like walking out of the house without clothing.

One size does not fit all, yes makeup can be oppressive for some women but it can be extremely empowering for others. Everyone wears makeup for different reasons.

With that said, I work in the cosmetics industry and I enjoyed learning about Helena Rubinstein’s story. The history of the beauty industry is an integral part of the history of women’s rights. I don’t think it’s a coincidence that the more rights women have gained the more popular cosmetics have become.

Great article.

What a fascinating article and piece of beauty history. Madame must have

been an incredible woman to have come from such humble beginnings and grown to such heights.

I skimmed this, to be read a little later….did she give thanks to her mother, I wonder?

carol ward, boulder, co

Make-up has always been used, we know because of cleopatra. It is fascinating as to what women will do. In the society now, we see that women can use things that will actually minimize their wrinkles around their eyes.

Make-up is wonderful. Me, on my 14th birthday in the 60’s bought a tube of a carmel smelling lipstick, my first, I applied it every hour I think. I felt like a real woman. My first loved fragrance was Youth Dew by Estee Lauder. I love old compacts and vintage solid perfume containers. Anyone saying negatives about makeup or perfume, are not looking at the good it does for a womans self esteem. Is it a lie, it’s pretend, not a lie.

This was so fascinating