As an appraiser on Antiques Roadshow and a consultant to Heritage Auction Galleries, Rudy Franchi is highly sought for his opinion on posters, from propaganda sheets made during World War I and World War II to travel posters printed for the Southern Pacific Railroad and London Underground. In fact, Franchi’s been a professional purveyor of mass-produced printed art since 1970, when he and his wife, Barbara, opened The Nostalgia Factory, whose specialty was movie posters.

Which may explain why Franchi didn’t expect to be impressed after he received a call last year from a college student, who said he had a roll of old posters he was trying to unload.

“The guy said his aunt had died and left him the contents of her antiques shop, which she had closed up years before,” Franchi told me recently. “As he went through her stuff, he found a roll of old posters. The aunt dealt in furniture, so the posters may have been in the drawer of something she bought—I’ve seen that happen five or six times. Posters weren’t her field, so she probably just put them aside.”

“It was like putting up posters for Yellowstone.”

The nephew, who like Franchi lives in Southern California, drove the roll of paper to the appraiser, seeking his advice. “The first sheet I pulled out was a rather dull, monochromatic litho from Europe, worth maybe 50 bucks,” Franchi recalled. “But as I started to go through them, I came across these 1930s railway posters from Japan, which I had never seen.”

Fifteen posters from that roll, all of which have been professionally restored and backed with linen, will be auctioned at Heritage on March 22, 2014, beginning at 5 p.m. CST (Internet bidding is open now but closes on March 21 at 10 p.m.). Opening bids for most start at around $250, but each could bring $1,000 or more. After the sale of the Japanese posters, Heritage will offer British and French railway and travel posters, also from the 1930s and also from the nephew’s cache, in subsequent auctions. “It’s a huge find,” Franchi says.

As it turns out, Franchi was not the only expert unfamiliar with these Art Deco-era Japanese railway posters. “As soon as we got them to the restorer, we started taking pictures, which I sent all over the world, including to the Victoria and Albert Museum, which has a fantastic poster collection. Some people knew what they were, to the extent that they knew Japan’s national railway had distributed posters in the ’30s, but they had never seen them. Even the curators at the Ogaki Poster Museum in Japan were stumped. They had heard about them and had some ideas about them, but they didn’t have any in their collection.”

“Autumn: Red Leaves and Onsen.” 24.5 x 36.5 inches. Osaka and Nagoya Rail Agency. Translation: “Discount on auto (bus) travel during October and November.”

The veil of mystery surrounding the posters probably has something to do with Japan’s place on the world stage in the 1930s. While much of the Western world was struggling from the effects of the Great Depression, Japan was expanding, with a growing economy and territories that included Taiwan and Korea, which was a popular destination for Japanese tourists. The 1930s was also the decade when Japan established numerous national parks, many of which featured natural hot springs and were accessible by Japan’s growing system of railways. “It was like putting up posters for Yellowstone and encouraging tourists to get there by train,” Franchi says.

“Even the curators at the Ogaki Poster Museum in Japan were stumped.”

Although no one can be 100 percent sure, Franchi says the posters were probably printed in editions of 2,000 or fewer. “We think the numbers were fairly limited,” he says, “because there were only so many places to distribute them at the time. They’d put them in railway stations, send them to classrooms, things like that. The marketing wasn’t very sophisticated back then. Low thousands is typical of what the Japanese would produce for domestic posters. You see tons of Japanese posters from the ’30s meant for international distribution, but these were internal.”

What you don’t see are images of the trains themselves, which are staples of Western railroad posters (although a few of the Japanese posters feature simple system maps). “Yes, that’s amazing,” says Franchi. “American railway posters invariably show a train, or the interior of a train, but that doesn’t seem to be the case with the Japanese railway posters of the 1930s. It wasn’t their tradition.”

And while the imagery may have been evocative, at times even romantic, the advertising copy superimposed on these depictions of waterfalls, landscapes, and seacoasts was no-nonsense, strictly business. In one poster produced by the Nagoya Rail Agency, showing the silhouette of a solitary backpacker gazing upon a celadon mountain range, the text reads, “Discount on auto (bus) travel during July and October. Other discounts also offered.”

(All images courtesy Heritage Auction Galleries.)

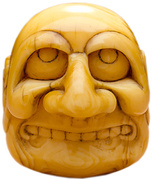

The Folklore and Fashion of Japanese Netsuke

The Folklore and Fashion of Japanese Netsuke

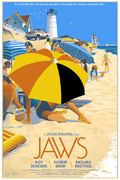

Welcome to the Retro-Futuristic World of Laurent Durieux

Welcome to the Retro-Futuristic World of Laurent Durieux The Folklore and Fashion of Japanese Netsuke

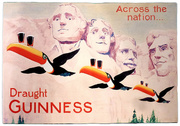

The Folklore and Fashion of Japanese Netsuke My Goodness! Guinness Collectors Snap Up Secret Stash of Unpublished Advertising Art

My Goodness! Guinness Collectors Snap Up Secret Stash of Unpublished Advertising Art Railroad Posters and AdvertisingAlmost immediately after the final spike was driven into the 1,912-mile Fir…

Railroad Posters and AdvertisingAlmost immediately after the final spike was driven into the 1,912-mile Fir… Japanese AntiquesJapan, with its history of seclusion, has long fascinated Westerners. When …

Japanese AntiquesJapan, with its history of seclusion, has long fascinated Westerners. When … PostersIn 1867, Jules Cheret, inspired by Japanese woodcuts, used the newly-develo…

PostersIn 1867, Jules Cheret, inspired by Japanese woodcuts, used the newly-develo… Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

The posters were obviously translated by a Chinese, not a Japanese. The word for auto (chiche) in Chinese is the word for train (kisha) in Japanese. There is no reference in the posters to auto or bus travel.

GREAT WRITE UP BEN!! :)

Fascinating story and it shows that there is always plenty more to discover.

Also, several place names were translated literally. The poster translated as “Standing on mountains” should read “Tateyama,” which is a mountain in Toyama Pref. The one that says “Golden Years (Retirement) in the Summer” is actually “Yoro in the summer.” Yoro is a town in Gifu Pref. where there is a waterfall just like that one in the poster. “Fields of Color” is actually “Kai,” referring to the old province name for Yamanashi Prefecture.