Following the attacks in Paris on Friday, November 13, media across the globe reported the discovery of a Syrian passport found near the body of one of the suicide bombers. “It remained unclear if the passport was authentic,” wrote the “New York Times.” Regardless of legitimacy, the document’s presence immediately stirred debate on the permeability of Europe’s borders, renewing calls to keep refugees out.

“Nearly every country that was occupied by German forces contributed or remained passive to the deportation and execution of its Jewish population.”

It seems strange to admit that in 2015, the right to exist in certain physical spaces on Earth—spaces bound by imaginary lines drawn on maps by our governments—can be prevented by a pocket-sized paper travel document. And yet, as millions flee Syria to escape continued violence, their lives often depend on a bit of official paper permitting transit to any number of safer countries.

In the early 20th century, the spread of compulsory passport usage coincided with the increasing stability of nation-states. Within this system of mutually recognized sovereignty, travel became dependent on official visas pasted or stamped into a passport booklet by each destination country’s authorized body. Passports provided governments a way of controlling the narrative, creating benchmarks for “illegal immigration,” and enforcing rules about who belongs where. But history has also shown that during periods of conflict, forged passports or visas are as likely to be utilized by government agencies as they are by desperate individuals. When the abstractions of law run up against the human instinct for survival, whom do passports actually serve?

Top: The interior of a 1916 Austrian passport belonging to a young Jewish refugee named David Oks. Above: The passport’s cover is labeled “Ausländer,” meaning “Foreigner.”

Nobody is more aware of these contradictions than Neil Kaplan, who has collected around 2,000 historic travel documents, many of which survived conflict in the Middle East and elsewhere. Kaplan was raised in Israel and first became interested in passports after a school assignment required him to ask neighbors about their experiences immigrating to Israel. Today, he divides his time between Tel Aviv and various locations in China, where he travels for work (and hunts for passports). On his website, Our Passports, Kaplan thoroughly examines each stamp and signature in every passport he finds, researching names, locations, and dates to construct the forgotten stories of their owners.

The use of official travel documents long predates the founding of modern nations: One of the earliest recorded examples comes from the Old Testament, circa 450 B.C. In the Book of Nehemiah, a prophet serving under King Artaxerxes I of Persia was given a letter directed at the rulers of lands beyond the Euphrates, asking for safe passage on to the Kingdom of Judah, where he was to rebuild the walls of Jerusalem.

Centuries later, “Jew” became the shorthand term for those who had been forcibly exiled from Judah. Beginning in the 1880s, as part of the Zionist movement to establish a self-governed Jewish state, this same land was flooded with successive waves of Jewish refugees escaping violent persecution across all parts of Europe and the Middle East. Some traveled with documents from their place of origin; others emigrated using forged papers created by Zionist activists; all coalesced into a new Jewish-majority community, known as Yishuv, in a region near the Mediterranean Sea, where they eventually established the State of Israel in 1948.

Today, several countries refuse to recognize Israeli passports, while many neighboring nations maintain a permanent refugee-status for their Palestinian inhabitants, denying them—and their children—the travel documents allotted to those with full citizenship. In the contested lands of the Middle East, passports remain a political tool as much as a transportation aid.

The oldest travel document in Kaplan’s collection is this American certificate issued in 1815. (Click to enlarge)

While much of Kaplan’s collection focuses on Palestinian, Israeli, and Holocaust-related passports, his earliest document is actually an American passport issued in London in 1815 to a Mr. William Story. Like most travel documents of this era, this example consists of a single folded sheet of paper imprinted with a request for the “protection” of the passport holder and a list of his physical characteristics—including his “high” forehead, “clear” complexion, and “average” mouth. The single-sheet certificate is written in French, the official language of diplomacy at the time, and was signed by future-president John Quincy Adams, who was then serving as the U.S. Minister to Great Britain.

The western word “passport” was derived from a French phrase—either “passe port,” meaning literally to pass through a ship’s port, or “passe portes,” describing the act of entering a city’s gates. This became the customary term for travel papers during the reign of King Louis XIV in the 17th Century, when those in the court’s favor could secure letters from the King to help make their journeys smoother. At this early stage in globalization, as people were increasingly able to travel beyond their country’s borders, passports became an enviable tool for those heading far from home. Eventually, these paper certificates grew into small cardboard-covered books, and in the latter half of the 19th century, passport applications spiked as more travelers could afford to take steamships and railroads.

However, during periods of relative peace, many governments came to view the documents as an annoying bureaucratic barrier. France decided to abolish the use of passports in 1861, followed by several other countries including the United States (though travel documentation was required for the duration of the Civil War). In the decades following, while passports were deemed irrelevant for white travelers, they were still used to deny entry to “undesirable” visitors to the United States, like those arriving from China. But in 1920, following the political chaos of World War I, the League of Nations finally established a firm set of international passport standards, including proper photographic identification.

Regardless of when they were made, the artifacts in Kaplan’s collection offer remarkable insight into the lives of ordinary people, revealing the intimate impact of travel restrictions and the ways desperate people have frequently evaded these laws. We spoke with Kaplan about the flexibility of passports in times of crisis and the secrets these documents hold.

A few of the historic passports from Kaplan’s personal collection.

Collectors Weekly: How did you become interested in travel documents?

Neil Kaplan: When I was growing up as a kid in Israel 25 or 30 years ago, every single person in their 60s or older had a story about the Holocaust. Nearly one out of every four or five would have a number marked on their hand, and if you asked what it was, they would smile at you and tell you it was from the camps. I didn’t understand it then, but as I grew up, I learned that most of them were liberated from these concentration camps, and they immigrated to British Palestine, which became Israel after 1948.

Up to the 1990s, we only had one channel on TV, and on Holocaust Remembrance Day, the Israeli TV station would show black-and-white news reels of ghetto life and the execution of Jews. It was not like today where people are more sensitive to children and what they’re watching. It had a strong psychological effect on all of us who were born in the ’70s and earlier.

In 1989, when I was 15 or 16, we were given school projects relating to anti-Semitism and the Holocaust. Back then, I lived about two or three miles from the center of town, separated from it by orange orchards, strawberry fields, watermelon fields, and chicken farms. About 10 families made up my whole neighborhood, and all the adults had escaped Nazi Germany in 1938 or 1939 after Kristallnacht. [During this riot, whose name translates as the “Night of Broken Glass,” German citizens and paramilitary troops murdered their Jewish neighbors and destroyed homes, businesses, and synagogues.] Then the Second World War broke out, so it became nearly impossible to get out of Nazi Germany.

A Jewish “kennkarte” or ID card issued in Germany in 1939. (Click to enlarge)

I decided to speak with one of my neighbors, whose job was raising chickens, about when he came to British Palestine. His name was Arnold, and he said, “I haven’t time right now, but you can go to my house, and in the cupboard, you’ll find an old leather bag that belonged to my father. Inside are some documents and papers relating to our immigration to British Palestine.” When I went to his house and turned the old bag upside down, all these documents came out from the end of the 19th century and the First and Second World Wars: There was a passport with the Nazi swastika and the big, red stamped “J” inside, and also a Kennkarte, another ID issued for Jews. Arnold’s father had been incarcerated at the Dachau concentration camp after Kristallnacht. He was one of about 30,000 wealthy Jews put into these camps by the Nazis, because he was head of one of the largest banks in a small town in West Germany.

When I picked up those passports at my neighbor’s house, and I saw the oval-shaped purple, black, and blue stamps inside, it had a big effect on me. I decided to speak to another neighbor, and then another and another. I spent the next three or four years speaking to all these people who were in the ghettos or the Jewish brigade, and people who were immigrants before and after the war. Among the war memorabilia they showed me were a lot of passports from the ’20s, ’30s, ’40s, and even after the war, for every country they had emigrated from.

In 1940, Jewish refugee Szulem Granek was issued this Lithuanian travel document, which he used to travel to British Palestine.

Collectors Weekly: How was your family affected by World War II?

Kaplan: My father’s uncles fought for the South African Army with the British forces in World War II, so they always had stories of fighting the Italians in Ethiopia and Somalia, moving all the way up through Egypt, and on to Italy and Germany. One of my father’s uncles was a guard at a POW camp in North Africa, guarding Italian POWs. That was also one of the camps where the British deported Jewish rebels from Palestine, the so-called “Zionist freedom fighters,” who attacked the British-ruled Palestine, leading to the independence of Israel in 1948. The British saw them as terrorists.

“Several diplomats decided to do the honorable thing—not to follow the rules and orders given by their foreign ministry.”

On my father’s side, those who were not in South Africa lived in Lithuania. In 1941, on Yom Kippur—one of the holiest Jewish holidays—the Einsatzgruppen or German death squad marched all of the Jews in their community into pre-dug ditches and gunned them down. The rest of my father’s family died in those ditches in October of 1941.

On my mother’s side, my grandfather and grandmother traveled from Romania to Hamburg, Germany, where they escaped on a boat all the way to Chile the summer just before the war erupted. Some of her other family members in Europe fled and joined the Soviet Red Army. At the end of 1944 or ’45, my mother’s grandparents died in the snow while being forcibly marched by the Germans.

My father grew up in South Africa and emigrated from Cape Town to London, where he lived for about 10 years. Then in the 1960s, he had an urge to try living in Israel because he was a Jew. My mother also came to Israel in 1970. She was born in Chile just before Pinochet came to power. Her family had left Chile and settled in Brownsville, Texas, but my parents met in Israel. Our family is very secular: We eat bacon and cheese, and we don’t go to temple. Besides being born Jewish, we don’t have any connection to the religion.

Collectors Weekly: What do you look for when researching a passport?

Kaplan: Each time I get a new passport, it is very important for me to examine every single entry inside, from the moment the person was issued the passport, to the visas they applied for or the countries they entered, to its final destination. Then, I draw a map in my head of all the places they went, and I make sure that if they entered one country, they also got a stamp for leaving that country. I check the signatures of the people who issued the visas or the passport itself. A very plain, boring passport might have a signature from a fascinating consul with a significant diplomatic history, and I might build the passport’s story on that consul’s signature. Sometimes you get a passport with three or four different signatures inside, and each signature could be the subject of an entire article.

One of the items I’m currently researching is a Polish passport issued in Shanghai in 1947. It has three different signatures inside, and each is interesting. For example, the Polish attaché who signed and extended the passport in Nanjing would later become Poland’s first ambassador to the People’s Republic of China in October ’49. I later found out that the person who owned the passport managed to flee Poland into Lithuania in 1939, and in 1940, he got a life-saving visa from the famous Japanese consul Chiune Sugihara. That took him all the way to Siberia, then to Kobe, Japan, and then to Shanghai. After the war was over, he received a new passport in 1948 in Shanghai with one of the earliest official visas issued by Israel. It was issued by Moshe Yuval, the only Israeli consul sent to China before official diplomatic relations were established nearly 50 years later in 1992.

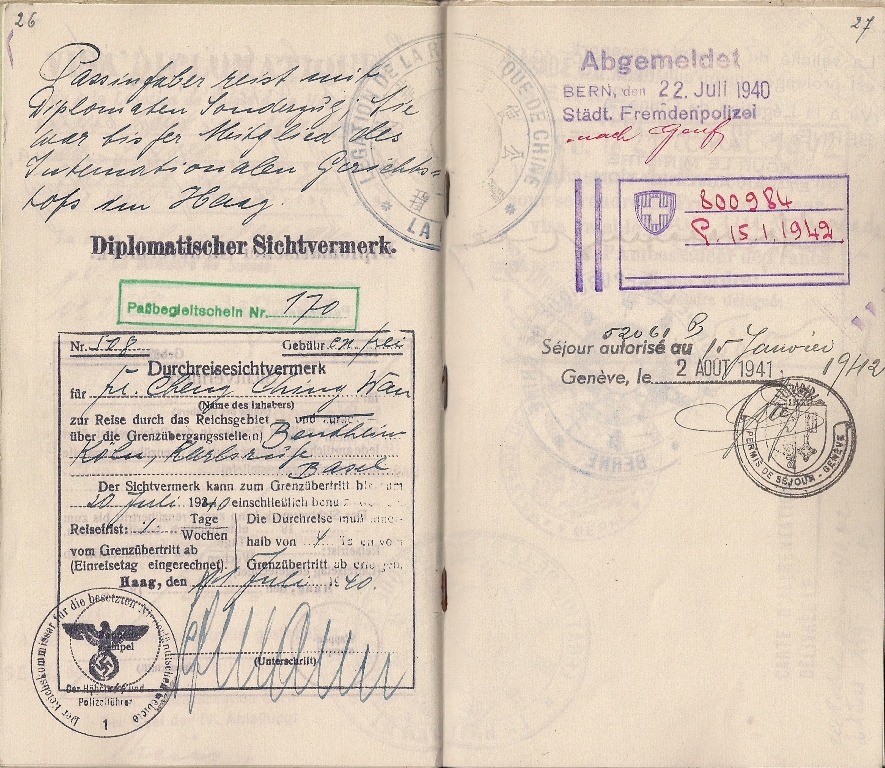

Cheng Ching Wan’s passport includes this rare 1940 visa, issued by the German SS, for a special diplomatic train used to escape occupied Holland for Switzerland. (Click to enlarge)

Collectors Weekly: How did specific diplomats use their position to save lives during periods of conflict?

Kaplan: Toward the end of the ’30s and into the beginning of World War II, most countries were very strict with their visa-issuing. I think these regulations were implemented specifically to prevent Jews from arriving in those countries. Sometime in October 1941, the Germans decided not to permit any Jews to leave their territory. They were implementing the Final Solution, so they weren’t allowing Jews to escape.

But at the time, several diplomats had something in them most people don’t, and decided to do the right, honorable thing—not to follow the rules and orders given by their foreign ministry. Many people who are under pressure or in danger decide not to help others, or freeze up because they’re not accustomed to this type of situation. Yet these diplomats understood that people’s lives were involved, and because of their integrity, they decided to act.

Chiune Sugihara was a Japanese vice-consul stationed in Kaunas, Lithuania, in 1939 to supervise the German and Russian forces as part of the Axis powers, and report back to Tokyo. Sugihara was given a “no” from the foreign ministry in Tokyo, but he still decided to help. The Soviets would not allow Lithuanians to cross into Siberia without a final destination, so Sugihara worked together with the Dutch consul in Lithuania to issue a ridiculous visa for travel to Curaçao, which was a small Dutch colony in the Caribbean. Once that was inside the passport, it was easy for Sugihara to give them a transit visa to Japan, where they could catch the boat to Curaçao, though the majority stayed in Japan.

The passport for Emil Jakubovic includes a visa issued by Chiune Sugihara to leave Lithuania for Curaçao via Japan. (Click to enlarge)

The Portuguese consul in Marseilles, Aristides de Sousa Mendes, was warned not to issue visas, but he still did so until the point that agents were sent to escort him back to Portugal. Others included Feng-Shan Ho, the Chinese consul in Vienna; Frank Foley, who was the British consul in charge of visas in Berlin; and Hiram Bingham, the U.S. vice consul in France.

When they returned home, Sugihara and de Sousa Mendes were stripped of all honor and their pensions, disgraced, and kicked out of the foreign service because they disobeyed the law. Today, they’re hailed by their governments as heroes and have statues erected in their honor, but back then, they were reprimanded at the highest level.

A few were not punished, like Raoul Wallenberg, at the Swedish embassy in Budapest. In 1944, Wallenberg issued special protective documents called Schutzpass to help Jews escape occupied Budapest, and I’m sure Swedish officials knew about it, but he wasn’t told to stop. He had a particularly sad ending, as he was arrested by the Soviets and presumably was executed or died in prison.

Life-saving visas issued by Arthur Whitall to a Jewish refugee, Szulem Granek, allowing him to leave Turkey for British Palestine in 1940. (Click to enlarge)

Collectors Weekly: What was the Habricha?

Kaplan: In Hebrew, “habricha” means “escape.” After the end of World War II, Jewish leaders in British Palestine known as the Jewish Agency for Palestine tried to rescue Jewish survivors from all across Europe. They understood that during the systematic destruction of the Jewish race in Europe, nearly every country that was occupied by German forces contributed or remained passive to the deportation and execution of its Jewish population. After the war, the Jewish Agency for Palestine dispersed its agents to every major city in Europe, and their job was to locate surviving Jews and bring them to Palestine.

Let me go a step back and explain the Jewish situation in Poland: When Germany invaded Poland from the West, thousands of Jews escaped to eastern Poland, which fell under Russian occupation, and eventually, they fled deeper into the Soviet Union. When the war ended, close to 100,000 Polish Jews returned to Poland, but they found that their Christian neighbors had taken their houses, their savings, and their businesses.

This form certified that Rywka Wercajzer, who worked with Habricha organizations, had been liberated from Auschwitz. Polish Jews used similar forged documents to remain in Germany and receive assistance from the Allies, rather than returning to persecution in Poland. (Click to enlarge)

The Christian Poles were angry that the Jews came back to claim their property, and they began to threaten and hunt the Jews. Surviving Jews in Poland began to flee into neighboring Czechoslovakia or even Germany, which was then occupied by the Allies. So the Jewish Agency opened offices under the guise of a welfare and educational institute, and began to smuggle them across the Czech and German borders. Then they were given fake IDs and passports, allowing them to enter into occupied Germany, Czechoslovakia, or Romania.

Without these fake passports or identification papers, they would have had a very difficult time getting welfare from the occupied allied forces in liberated Germany. They were not supposed to go to Germany; they were supposed to stay in their native Poland. But if they had fake documents that attested to them being Austrian or German or Romanian or French, then they could get proper food and assistance because they were being repatriated. That’s habricha in a nutshell.

A 1951 Israeli diplomatic passport for Ehud Avriel, an activist who helped many Jews flee Europe for British Palestine. (Click to enlarge)

Collectors Weekly: Why did countries like the United States deny entry to Jewish refugees facing violence in their home countries?

Kaplan: It’s a big question. Prior to World War II, when Jews wanted to flee Germany, the West did not want to help them. The Americans filled their quotas, and the British closed the borders into Palestine. Most countries around the world wouldn’t provide visas when they realized it was Jews who were trying to immigrate, making it much more difficult. Accepting refugees is also partly an economic issue, be it in the 1930s or today. It sounds cold-hearted to put it this way, but you’re costing the taxpayers, so it’s a financial burden to them. Chunks of money are spent to help refugees, and that’s the economical point of view from these governments. People say, “Oh, what a pity! We should help the refugees.” But they don’t recognize that if they help them, someone else will not get this government money.

Israeli Jews are very familiar with the issues of refugees. Because all these refugees began to flood Western Europe after the First World War, the majority of them Jews fleeing anti-Semitic attacks, the League of Nations began holding conferences regarding displaced people. Fridtjof Nansen, a Norwegian diplomat, was one of the first to confront the issue after the First World War. He was named High Commissioner for Refugees by the League of Nations, and in the 1920s, they issued specific travel documents for refugees called Nansen passports.

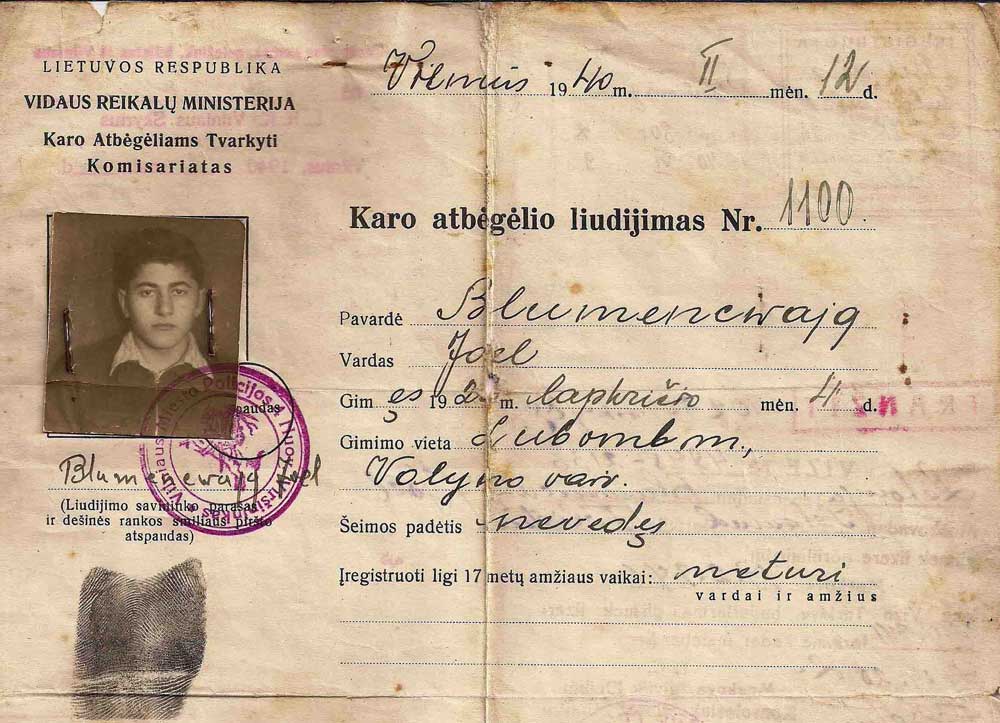

Part of a rare War Refugee Certificate issued to Joel Blumencwajg in Lithuania in 1940. (Click to enlarge)

Passports can generally be divided into four main types: You’ve got your regular passports. Then you have diplomatic passports issued to consuls, diplomats, ambassadors, attachés, or government officials. Service passports, or what Americans call “official passports,” are for government workers traveling for a specific reason, for example, going to the U.K. for six months of training or to attend a special conference on energy. They’re in between a regular and diplomatic passport.

The fourth type is a travel document used by a holder who is not a citizen of the country that issued it. Refugees or people without a fixed national status can apply for these documents so they can travel abroad.

Collectors Weekly: How did British Palestine, and later Israel, handle such a tremendous influx of refugees?

Joel Blumencwajg’s acceptance letter from the British Consulate authorizing his immigration to British Palestine.

Kaplan: It’s a bit of an enigma, and it’s actually unique to Israel. In a period of less than 10 years, we accepted enough refugees to triple the existing population. A lot of assistance came from international Jewish organizations or donations from wealthy Jews in the Western world. When refugees came to Israel, they were sheltered in makeshift tents and shacks on the outskirts of every major city and lived there for the few years until they could be moved into special government houses.

Israel also implemented a strict rationing system, or austerity, meaning that food was extremely limited from 1949 to 1959. Each family would be given something like one or two eggs in a week, half a kilo of meat for two weeks, or one fish per month. That’s a rough example. The government issued special, controlled coupons, and you wouldn’t be able to get butter or coffee or chocolate unless you had these vouchers. With them, you could go to special outlets with long queues and apply for your eggs or chocolate. Because of the tight control over resources, they were able to give food to hundreds of thousands of immigrants. Today, the West wastes food and throws tons into the garbage—what they throw away could feed countless people around the world.

Collectors Weekly: When did Israel begin issuing its own passports?

Kaplan: Israel didn’t issue its first passports until the end of 1952. For the first four or five years after the country was established, they had a “laissez-passer” travel document in lieu of a passport because Israel also didn’t have its own citizenship law until 1952. From 1948 until 1952, Israel had three types of travel documents: The first version, a 16-page cardboard booklet, appeared from the end of 1948 until the end of 1949. They didn’t even have the emblem of the state of Israel, the menorah or Jewish lamp with seven candlesticks. From the end of 1949 to the end of 1950, Israel issued another document, with double the amount of pages and the emblem of the state of Israel as we know it today. Then from 1950 until 1952, they issued the last version, which looks identical to an Israeli passport with the standard blue cover, but it does not say passport—it says “travel document” or “laissez-passer.”

The Saudi Arabian stamp in this American passport from 1950 indicates that any attempted travel to Israel invalidates the visa.

All the Arab countries and some Muslim-majority countries, like Indonesia and Malaysia, refused to accept Israeli passports. Anyone with a passport bearing an Israeli visa or entry stamp into Israel was automatically not permitted into the Arab countries. I’ve got some passports that have stamps as early as 1950, indicating in English and Arabic that the visa was no longer valid if the passport holder later applied for an Israeli visa.

Collectors Weekly: How have governments used passports as a way of maintaining power in times of crisis?

Kaplan: When you look at countries run by totalitarian regimes or dictatorships, like the Communist Eastern Bloc after World War II, it was nearly impossible to leave these countries and emigrate elsewhere, because most people would have loved to escape those horrid governments. They used passports to prevent people from leaving, controlling their own civilians by keeping them inside the country.

The cover of a forged Polish passport.

Instead of passports, the Soviet Union issued internal passes, and each bus or train station would have the security guards to inspect and make sure everyone had the exit permit, allowing them to leave the area and travel inland to another location. Soviet-issued passports from the 1920s and the 1930s for Jews immigrating to Palestine are very rare. They hunted down Jews who were thinking about leaving because they believed Zionism was counterrevolutionary.

Polish passports from between the two World Wars are a passion of mine. After collecting 20 or 30 of them, I realized there was something strange about a specific period in 1939—after the Germans and Soviet invasions in September. A lot of passports were issued in Romania and Hungary during a period of about two months, and almost all of them had visas allowing the passport holder to escape into France or the U.K., where they were building a Polish army.

These were emergency passports, issued to civilians and soldiers in three main locations: Budapest, Bucharest, and Chernovich. All those consulates issued regular blue-covered Polish passports, and when those ran out, they began to print them locally on large, folded A4-size paper. Then, they began to forge them. I have one of those passports, most likely forged by the Polish embassy in Budapest in October, 1939, and preprinted with visas and stamps inside, all in color. You only had to fill in the holder’s name, his details, and a photograph, and you had a used-looking passport to help you escape to the West.

Up until 1939, every city in Poland had a Ministry of the Interior, which would issue passports. When the Communists took over Poland in ’45, their issuing authority was the Foreign Ministry, and the only location was in Warsaw. That’s another way a government can control its people and prevent them from leaving, by altering the regulations for the issuing of passports.

The inside of Kaplan’s forged Polish passport was already marked with official stamps, waiting for an escapee to add their details and photograph. (Click to enlarge)

Collectors Weekly: What triumphs or tragedies have your passports revealed?

Kaplan: One of the first passports I got back in ’89 was from one of my neighbors, a very old Czech woman. She gave me her father’s passport, and told me her father left on one of the last trains from Prague when the Germans marched in from the West on March 15, 1939. When you look inside the passport, there’s a Polish visa that was given to him five days before the Germans invaded, and it was only valid for five days. It’s indicated on the visa that he was allowed to enter the country for 24 hours under police guard from the Polish border all the way to Romania. His exit mark is actually from the 15th of March, 1939. So she was telling the truth. He boarded a train out of Prague only hours before the Germans marched in, and it’s all marked and stamped inside his passport. You can imagine how he might have missed the train or decided not to leave that day, and he would’ve ended up in the camps.

A rare exit visa from Łódź, Poland (or Lodsch in German), in a Jewish woman’s passport that was extended by the German occupying forces even as Jews were being forced into the city’s famous ghetto. (Click to enlarge)

After Germany invaded Poland in 1939, they stopped accepting prewar Polish passports or ID cards. The Poles had to take their prewar ID cards and have them stamped and registered, and then a few months later, in the beginning of 1940, the German government issued brand new ID cards for the occupied sections of Poland. Polish passports were no longer valid and accepted because, to the Germans, Poland did not exist anymore, so the chances of leaving occupied Poland were very, very slim. They might allow you to travel to Nazi Germany or to other sections of occupied Poland with special internal permits.

But I came across a Polish passport, which was issued in 1932—a prewar passport—that was extended by the German occupying police for an extra year. The Jewish woman who held this passport must have had connections or a lot of money, and probably bribed the officials in Germany to allow her to leave the ghetto in 1940, apply for the German occupational exit visa and then the transit visa from the Italian consulate. The passport was extended properly by the German authorities, who permitted her to use a prewar Polish passport to leave occupied Poland. She couldn’t apply for the transit visa into Italy without having the German exit visa or permission to leave. Then she traveled to Italy and, from there, to British Palestine.

Collectors Weekly: Do your passports also conceal any secrets?

Kaplan: I have some World War II passports, which are filled with visas for many, many countries. All these passports were issued to seemingly ordinary citizens. But when you look at the destinations and types of visas, there’s no way that this person could’ve actually been a bookkeeper, or hairdresser, or a car mechanic. They had special visas taking them to over 90 countries, countries you wouldn’t even know existed.

For example, I’ve got an American passport issued in the ’40s to a man who went all over the world, nearly every single country in Asia, South America, Europe, and Africa, but it says he was a cosmetician. There’s no way this guy was a regular cosmetician and traveling to all the countries in the world. Another passport is an Israeli passport belonging to an engineer, but he spent six years traveling through every single country in East and West Europe. That’s why I think that these people are not who they appear to be.

Most countries—throughout the Second World War and afterwards—produced passports with forged identities in order to travel to other countries to conduct espionage. The holders of these passports could have been working for government intelligence or the military. They could have been contractors or merchants buying raw materials for war production. It’s a mystery.

In the early 1950s, this passport for an alleged cosmetician from Los Angeles, California, took him all over the world to places like New Zealand, Burma, Algiers, the Cook Islands, Singapore, and Allied-occupied Germany. (Click to enlarge)

(All images courtesy Neil Kaplan. For more amazing documents, visit Our Passports.)

Why Would Anyone Collect Nazi?

Why Would Anyone Collect Nazi?

What America Can Learn From Berlin's Struggle to Face Its Violent Past

What America Can Learn From Berlin's Struggle to Face Its Violent Past Why Would Anyone Collect Nazi?

Why Would Anyone Collect Nazi? Collectors on a Mission: When Americans Saw the World Through Evangelists' Eyes

Collectors on a Mission: When Americans Saw the World Through Evangelists' Eyes Passports and Travel DocumentsAlthough paper travel documents have been around at least since Biblical ti…

Passports and Travel DocumentsAlthough paper travel documents have been around at least since Biblical ti… Politics and Public ServiceHistory is often told through the grand detritus of the political sphere—th…

Politics and Public ServiceHistory is often told through the grand detritus of the political sphere—th… Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

As a naturalized US citizen for over 40 years, I still can’t understand why my passport has to state my place of birth and why my national origin has any importance in my identification. Does it mean that I’m less of a citizen or do I deserve more scrutiny?

“all coalesced into a new Jewish-majority community, known as Yishuv, in a region near the Mediterranean Sea, where they eventually established the State of Israel in 1948.”

That gives a false impression that the Jews were able to become the majority in that region. In the region called Palestine the Jews were only 3% of the population at the start of 20th century and even after mass migration through the next decades they were only 34% of the population of Palestine. The UN 1947 partition plan allocated 55% of the area to the nJews and relegated the majority natives of the 45% of the less desirable land. When Israel announced its creation of state it had occupied 78% of the land and ethnically cleansed out more than 700,000 Palestinians and it refused to allow them to come back. Many Palestinians still have the keys to their homes which they symbolically held on to and wish to return to their homes but they are not permitted to enter the country but if you and I convert to Judaism today we can get instant citizenship of Israel. This interesting bit was missing from the article.

Hunter:

Well done.

Each generation needs to be reminded and educated about how we migrated from one country to another.

Most of us in America are descendants or first generation Americans.

“It seems strange to admit that in 2015, the right to exist in certain physical spaces on Earth…”

This is, perhaps, one of the most asinine statements I have ever read. Quit conflating someone’s right to exist (to be alive, in other words) with someone’s ability to enter a space legally.

Im grateful for the blog article.Much thanks again. Cool.

Thanks for the article. One of the main reasons I collect passports is that most have an interesting story inside.

Thank you for this excellent article. This might be an interesting concept to collect vintage passports to augment my stamp collection.

“It seems strange to admit that in 2015, the right to exist in certain physical spaces on Earth—spaces bound by imaginary lines drawn on maps by our governments—can be prevented by a pocket-sized paper travel document.”

Exactly! This is the most precious part of the article, the heart of it.

Passports have a very special meaning to me because I am a world traveller, the visas and stamps in it are a testimony to my life. However, after bumping on too many imaginary lines and feeling the injustice of it on my bones, I started loathing what passports signified. So at the beginning of my third round-the-world tour I said I’d be travelling to every country and then burning my passports. Now, at 149 countries out of 195. You bet many of those visas are so special to me, especially those of the rarely visited countries. Each one has a story. Some of them are very artistic. It really is going to hurt to destroy my passports. But passports are unacceptable because they represent global apartheid or what I call birthplace racism. One day, they’ll be relics of the past. I just hope sooner rather than later.

http://www.gulin.world

And to see someone has commented that that sentence is the most asinine he has ever read!

He doesn’t go on to explain why it is asinine. I mean he says it’s conflating someone’s right to be alive with someone’s ability to enter a space legally but what does it mean to enter a space legally? He doesn’t put that question. Which space are we talking about? It’s not someone’s home, a private space, it’s a space some people of power have drawn, arbitrary lines, constructs of us. Borders are lines drawn by either bloody wars, or by metaphorically bloody politics. And blocking people’s movements on the world they are born just based on the imaginary line they were born is nothing but madness. Apart from being apartheid and racism in a global scale.