The queens had finally had enough: In August 1966—fifty years ago this month—transgender and gender-nonconforming customers at Gene Compton’s Cafeteria stood up to years of abusive, discriminatory treatment by the San Francisco police. The all-night restaurant in the city’s impoverished Tenderloin neighborhood was an unwilling haven for queer residents, and after its management called law enforcement to remove a noisy table of diners, patrons frustrated with the constant profiling and police harassment started throwing plates, cups, trays, and silverware at the officers. While police waited for backup, customers tore the cafeteria apart and the riot spread onto nearby Turk and Taylor Streets, damaging a police car and burning a newspaper stand to the ground.

“But if I could barely pay rent or buy food, how in the hell was I going to have a sex change?”

Three years before the Stonewall riots in New York City, which most Americans consider the watershed moment for gay rights, transgender citizens of San Francisco took to the streets to demand better treatment and to hold their harassers accountable. As often happened when marginalized queer people fought back against oppression, their voices were silenced and their existence was criminalized. Although the conflict at Compton’s was mostly ignored by the media, including publications run by the nascent gay community, 1966 would prove a major turning point in the battle for transgender civil rights, a year when cultural shifts aligned to begin improving the trans community’s access to healthcare and its relationship with law enforcement.

In 2005, Susan Stryker shed light on this moment with her excellent documentary, “Screaming Queens: The Riot at Compton’s Cafeteria.” Soon after, Stryker completed a book entitled Transgender History, which placed the rebellion at Compton’s Cafeteria in context among other moments of resistance to state-sanctioned violence and milestones in the march towards transgender acceptance. Several gender-nonconforming residents who spent time in the Tenderloin and experienced abuse firsthand have since spoken out, including two women who spoke with us for this story.

Half a century after the riot at Compton’s, transgender issues have finally become part of our national political conversation, and yet trans history is still overlooked, or conveniently ignored. For many Americans, the current panic over public bathrooms is the first time they’ve really considered the experiences of trans people, even though the debate over gender presentation dates back at least to the mid-19th century.

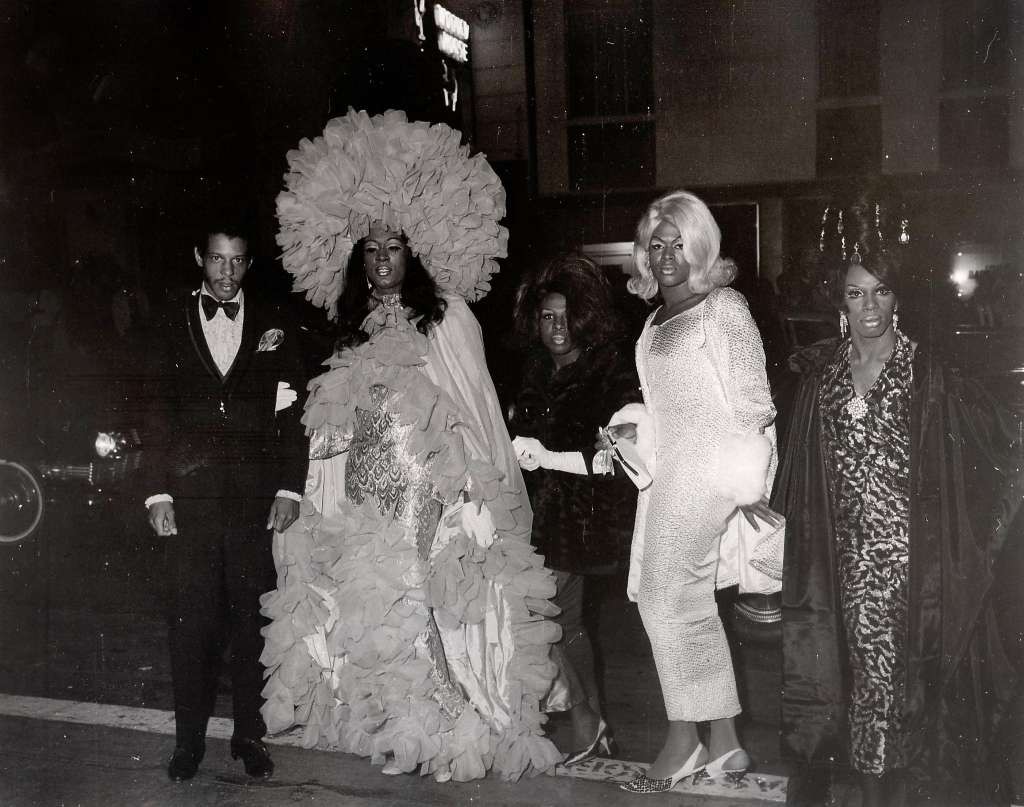

Top: Guests arriving at a Tenderloin drag ball, circa 1965. Photo by Henri Leleu. Courtesy of the Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Transgender Historical Society. Above: The exterior of the Powell Street location of Gene Compton’s Cafeteria as it appeared in the 1960s.

In the 1850s, as urbanization changed the fabric of American society, many cities passed local laws forbidding men or women to appear publicly in clothing associated with the opposite sex, an act that became known as “cross-dressing.” In part, these regulations were spurred by the first-wave feminists who argued that women should be able to wear male clothing styles, like pants, that were less restrictive and more utilitarian.

For men, the situation was different. Long before women were encouraged to achieve economic independence from their families, cities gave men the freedom to live on their own and form underground queer and proto-transgender subcultures. The anonymity of urban communities also allowed some individuals who were assigned female at birth to take on male identities in order to work and live on their own, like those who enlisted as soldiers during the Civil War. However, there are few verified examples of people in this period adopting a gender different from that assigned at birth, since in order to survive, their biological sex had to be kept secret.

At the time, there was no Western concept of transgender existence, as academics were only just beginning to parse the distinctions between sexual orientation and gender identity. In the 1860s, the German writer Karl Heinrich Ulrichs anonymously published his support of a biological view of sexual desire, using the label “Urning” to describe a man who desires men, which he envisioned as a female spirit within a male body. (In an 1869 letter written to Ulrichs, Hungarian journalist Karl-Maria Kertbeny first coined the terms “heterosexual” and “homosexual.”)

Dr. Magnus Hirschfeld (second from right, in glasses) with community members dressed for a costume party at the Institute for Sexual Science in Berlin, circa 1920s.

A few decades later, a biological explanation for transgender experience was promoted by Dr. Magnus Hirschfeld in Berlin. In 1897, Hirschfeld cofounded the Scientific Humanitarian Committee, a group promoting social and political changes to reduce the stigma and mistreatment of sexual minorities. Hirschfeld would later edit the “Yearbook for Sexual Intermediaries,” create the word “transvestite” to describe individuals we would call “transgender,” establish Berlin’s Institute for Sexual Science, and coordinate the first male-to-female genital operation for Dora Richter, which was completed in 1931. That same year, artist Lili Elbe underwent similar surgery, though she died of complications shortly after the procedure. (Elbe’s transition was recently translated to film in “The Danish Girl,” while Hirschfield and his institute were depicted in the Amazon series “Transparent.”)

Danish artist Lili Elbe, pictured here in 1926, underwent one of the earliest gender reassignment operations in 1931.

But in the 1930s, the events leading to World War II halted European advances in the study of gender. Upon his rise to power, Hitler condemned Hirschfeld’s work, and Nazis destroyed the Institute for Sexual Science in 1933, a moment captured in some of the most famous photos of fascist book burnings.

Following the war, doctors and activists in the United States continued to build on Hirschfeld’s biological approach, with San Francisco eventually emerging as a locus for innovative transgender healthcare and community organizing. In 1942, the Langley Porter Psychiatric Clinic opened at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF), quickly becoming one of the world’s top facilities for research on sexual and gender minorities. However, when one of UCSF’s transgender patients attempted to seek gender reassignment surgery in 1949, doctors declined her request, following the legal advice of the California Attorney General: The clinic was afraid a court would find the procedure constituted the crime of mayhem, or willful injury to a healthy person.

But in 1952, Christine Jorgensen became a role model and unofficial spokesperson for the transgender community after undergoing genital transformation surgery in Denmark. Jorgensen returned home to the United States under intense public scrutiny, at a time when the country was already anxious over gender roles upended by the war, and skyrocketed to international stardom, not only because she willingly discussed her transition, but also due to the shock value of an attractive young woman who’d previously served as a man in the U.S. Army.

Though media coverage of Jorgensen’s 1952 transition was extremely sensationalist, she became a role model and beacon of hope for transgender people around the world.

Meanwhile, Alfred Kinsey’s famous studies Sexual Behavior in the Human Male and Sexual Behavior in the Human Female were published in 1948 and 1953, respectively, adding to the larger conversation on gender and sexuality. During the following decade, a national gay-rights movement launched with so-called “homophile” organizations established in several American cities. Homophile activists mostly focused on moderate solutions achieved through private meetings with elected officials, but as the groups multiplied, a few adopted the nonviolent protest strategies of the burgeoning Civil Rights Movement. Beginning in 1965, East Coast homophile groups organized a small yearly protest called the “Annual Reminder” at Independence Hall in Philadelphia, with a strict conservative dress code to impress upon spectators that these ordinary Americans were being denied their Constitutional freedoms.

By this time, the Tenderloin neighborhood of San Francisco had become a refuge for young people who didn’t fit into America’s strict gender binary, like trans activist Felicia “Flames” Elizondo. When Elizondo was in her teens, she had moved with her family to San Jose, California. One of Elizondo’s first boyfriends, an older married man named Wally, first brought her to the Tenderloin, as it was a place they could be seen together without attracting unwanted attention. “That was when I was around 15 or 16,” she says. “We started coming to San Francisco a lot, so we knew all the bars, and the Tenderloin was the gay mecca of San Francisco.”

A program for a drag show at Finocchio’s, circa late 1940s, when San Francisco’s booming naval industry helped the city’s queer nightlife blossom.

Since the late 19th century, the Tenderloin had housed much of San Francisco’s working class in the small rooms of its many residential hotels. Its raucous nightlife and proximity to touristy Union Square and high-traffic Market Street also made it a haven for vice. In part, this was because the city’s corrupt police department allowed mob-run industries like drug dealing, gambling, and prostitution to flourish in the district as long as officials got their cut of the profits. (The neighborhood’s name references a prime cut of meat, likely referring to the desirability of the beat among local cops.) Because of the area’s reputation for relaxed morals, the Tenderloin was where some of San Francisco’s first gay bars opened, like the nautical-themed Gangway on Larkin Street, which was the site of a police raid against same-sex activity as early as 1911.

Following World War II, as middle-class residents began leaving the inner city for homes in the suburbs, the Tenderloin grew even seedier, while much of its freshly vacated housing was filled with the city’s poorest residents, including recent immigrants, people requiring supportive housing, and gender-nonconforming individuals. “That was the only place that would rent to us,” says Elizondo, who moved to the Tenderloin in the mid-1960s. “It’s where I met all the other queens and kids that were gay, though I don’t think they would’ve even called each other ‘gay’ yet. We were just queer sissies at the time. There were queens, sissies, female impersonators, and hustlers, all living within that four-block radius.”

An essay titled “Tenderloin Transexual” from Volume 1, Issue 9, of Vanguard Magazine, 1967. Courtesy of the Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Transgender Historical Society.

Before LGBTQ Americans had coalesced into a major political movement, the term “transgender” wasn’t widely used—instead people adopted a variety of self-descriptive labels like hustler, butch, drag queen, sissy, or hair fairy. “Transsexual” was the popular term used to specify someone who’d undergone gender reassignment surgery.

Gustavo Villarreal, also known as Donna Personna, began visiting the Tenderloin as a teenager in the 1960s, riding the Greyhound bus up from her family home in San Jose to wander the city streets. “Historically, the Tenderloin was where the outsiders or the marginalized people were put,” Villarreal says. “I was looking for something that seemed gay or queer, and I saw these guys that were selling their bodies—hustlers. I wasn’t purchasing anything; I just hung out with them. Somehow or other on my journeys, I discovered Gene Compton’s Cafeteria.”

Villarrreal, left, and her friend Bobbie pose in a photoshoot during the late 1960s.

In the thick of the Tenderloin at 101 Turk Street, Compton’s Cafeteria became a popular hangout spot for the neighborhood’s queer residents, particularly in the late hours of the night when sex work was most active. “It was open 24 hours a day, and you could see everybody you knew and parade your fashion or your boyfriend around,” Elizondo says. “It was our social gathering place at that time.”

Around the same time, a nearby section of Polk Street was transforming into a queer commercial corridor, though mostly aimed at middle-class gay men. In 1962, a group of bar owners in the area formed the Tavern Guild—the country’s first gay business association—to work against harassment and protect their businesses from unwarranted police closures. Yet many of these same bars closed their doors to transgender or gender-nonconforming customers. “None of the gay bars allowed us in,” says Elizondo. “The mixed bars did, like the Body Shot, the Rendezvous, the Frolic Room, the 181, and Gene Compton’s Cafeteria. But the rest of the bars, they wouldn’t allow queens in if we looked like sissies.”

One of Elizondo’s earliest friends in the neighborhood, Ciro, was a self-proclaimed hair fairy, meaning he wore his hair long, rather than relying on wigs. “Ciro told us he was a ‘hair fairy’ because it was against the law to dress like a girl,” she says, though he showed Elizondo how to do makeup, rat her hair, and pick out the latest angora sweaters and skin-tight pants. “There were men who performed as female impersonators and dressed like women, but they had to go into the club looking like a boy and come out as a boy, or they’d be arrested.”

Late-night diners at Compton’s, circa 1960s. Photo by Henri Leleu, courtesy of the Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Transgender Historical Society.

Gay and lesbian residents often exhibited prejudice toward gender-nonconforming persons, even as they fought against discrimination themselves. “Under the hierarchy of the gay umbrella, hair fairies were bad, flaming queens were horrible, and transgender women were the worst,” Villarreal explains. “Your parents didn’t like you, society didn’t like you, and your own community didn’t like you. Everybody hated transgender people—they were at the very bottom.

“Under the hierarchy of the gay umbrella, hair fairies were bad, flaming queens were horrible, and transgender women were the worst.”

“Whenever trans women were spotted in San Francisco, they would be corralled by the police and harassed incessantly,” she says. “They were physically constrained to the Tenderloin and told, ‘You don’t belong in these other neighborhoods.’ They’d go to jail for wearing a blouse or a dress, and they couldn’t even buy clothes that matched the gender they felt they were. If you were lucky, you could get a woman to go shopping for you—but if not, you had to steal them.”

Even harder than finding a dress was finding a job or an apartment. Because of overt discrimination as well as constant targeted policing, most transgender individuals couldn’t get hired for traditional jobs, and were forced to turn to sex work, drug dealing, or other illegal activities in order to survive. “Maybe the first time they ever went to jail was for dressing as a woman,” Villarreal says. “Everybody needs somewhere to sleep and something to eat, but they couldn’t work anywhere. So they took up the ‘criminal’ life because they were forced into it. I didn’t identify as transgender when I was spending time with these women, because I saw it as too much work. It was like trying to swim upstream—a continuous battle and hardship—and it was too much for me to want it that badly.”

Villarreal remembers it being typical for several young trans women to bunk together in a single studio. “I went to the hotels where they lived, where seven or eight girls would share a hotel room by the month,” she explains. “They designated hours that each of them could sleep, and then took turns. That’s the only way they could afford a place. But they didn’t bring johns there, and they never suggested that I should dress like a woman or asked if I wanted to prostitute myself. They looked after me, and I admire them for that.”

Members of the queer youth organization Vanguard participate in a Market Street sweep to clean up the Tenderloin, as seen in Vanguard Magazine Volume 1, Issue 2, from 1966. Courtesy of the Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Transgender Historical Society.

As the 1960s went on, police harassment worsened along with the deepening crisis in Vietnam: Because San Francisco was a major military deployment center, city officials encouraged vice crackdowns (supposedly as an effort to keep troops ready to fight), particularly for gay bars which catered to closeted military men. Transgender women were frequently arrested on “suspicion of prostitution” when going about their daily lives—their only suspicious behavior being their gender presentation. As Stryker explains in her book, “They might be driven around in squad cars for hours, forced to perform oral sex, strip-searched, or, after arriving at the jail, humiliated in front of other prisoners. Transgender women in jail often would have their heads forcibly shaved, or if they resisted, be placed in solitary confinement in ‘the hole.’”

Elizondo remembers bars with signage warning patrons to enter at their own risk because of the regular police raids. “The cops could arrest you for anything, like for standing too long on the sidewalk, or walking down the street,” Elizondo says. “When they hadn’t met their quota of arrests, they’d come to the Tenderloin and lock us up.”

A short article on the Vanguard protest at Compton’s Cafeteria appeared in the gay newspaper “Cruise News & World Report” in August of 1966. (Click to enlarge)

Official disdain for trans residents also meant that crimes against them were rarely investigated. “A lot of girls got killed and robbed. I think one of the girls got thrown off a second-story floor,” Elizondo continues. “You see, the trouble was, people would come to the Tenderloin to start a new life, but we didn’t know where they’d come from or their real names or anything. It was like opening a door and going through to the other side, becoming a brand new person. I was Bob; I was Diane; I was all kinds of names.”

By the summer of 1966, relations between the disenfranchised queer residents and San Francisco officials were strained, to say the least. In July, a group of LGBTQ youth in the Tenderloin founded Vanguard, which organized public demonstrations and published a self-titled magazine promoting tolerance and social justice. Vanguard held many of its meetings at Compton’s Cafeteria and its members recognized the increasingly discriminatory behavior of the restaurant’s management towards its gender-nonconforming customers. On July 18, working in partnership with other homophile groups, Vanguard staged a picket line protest at Compton’s, though the restaurant remained unsympathetic to their pleas.

That same month, Dr. Harry Benjamin published his groundbreaking book, The Transsexual Phenomenon, which challenged the American medical and legal establishment’s opinions on trans healthcare. Though Benjamin had lived in the United States since the 1920s, he was originally from Germany, and had been acquainted with Hirschfeld and the Institute for Sexual Science since 1907. “Benjamin essentially argued that a person’s gender identity could not be changed, and that the doctor’s responsibility was thus to help transgender people live fuller and happier lives in the gender they identified as their own,” Stryker writes.

At the time, American doctors often treated transgender individuals as though they were delusional, refusing to prescribe hormones and surgical treatments European professionals had used for more than 50 years. As Stryker explains in her book, “Doctors in the United States had always been reluctant to do so, however, fearing that to operate or administer hormones would only be colluding with a deranged person’s fantasy of ‘changing sex’ or would be enabling a homosexual person to engage in perverse sexual practices.”

Susan Stryker’s 2005 film, “Screaming Queens: The Riot at Compton’s Cafeteria” brought attention to the oft-forgotten event.

Sometime in August, mounting frustrations boiled over during the late-night confrontation in the Tenderloin, with the San Francisco police and Compton’s Cafeteria bearing the brunt of residents’ anger. “When the riot at Gene Compton’s Cafeteria happened, most of us didn’t know anything about it,” Elizondo says. “It wasn’t really important to us at the time; the queens were just trying to survive. Vanguard was doing political organizing, but we were trying to pay rent or to buy food. We weren’t worried about organizing, you know what I mean? After the riot, it was like nothing ever happened. It wasn’t covered in the media; it wasn’t in the newspapers. When you think about its larger place in history, it was just another time the police harassed us.”

LGBTQ people had protested discrimination in several instances prior to the turmoil at Compton’s, like the fight against arrests at Cooper’s Donuts in Los Angeles in 1959 or the picket line and sit-in at Dewey’s lunch counter in Philadelphia in 1965. But each was an isolated event borne of exasperation with the community’s treatment by local businesses and law enforcement.

A flier and photograph from the February 1967 demonstrations against a police raid of the Black Cat Tavern in Los Angeles. (Via Wikimedia)

In part, these riots weren’t widely celebrated because the status of queer people remained unchanged, and in the following months, police continued to harass and arrest gender-nonconforming folks at random. “I don’t think it made much of an impact or really changed things,” Villarreal says. “Things didn’t get better for the transgender community immediately after the riot at Compton’s. The gay community didn’t care enough about the transgender community, and the transgender community themselves had no power whatsoever—they didn’t have the wherewithal to pick up a banner and keep marching.”

“When you think about its larger place in history, it was just another time the police harassed us.”

However, many institutional changes did arrive on the heels of the protest at Compton’s: In the fall of 1966, the Central City Anti-Poverty Program Office opened in the Tenderloin, whose efforts included the creation of a new police-community relations officer, which was first filled by Elliott Blackstone, who brought his compassionate perspective to the position. “Blackstone worked to dissuade his colleagues in the police department from arresting transgender people simply for using the ‘wrong’ toilets or cross-dressing in public, and he promoted many other progressive attitudes toward transgender issues,” Stryker writes.

In November of 1966, Johns Hopkins Medical School launched the first gender reassignment program in the U.S., combining scientific research on the biology and psychology of gender with individual patient evaluations for hormone and surgery treatment. Around the same time, San Francisco’s Public Health Department launched its own transgender health initiative as part of the Center for Special Problems, which offered group support sessions, psychological counseling, hormone prescriptions, and eventually surgery referrals to a Stanford University clinic that opened in 1968. The Center for Special Problems also provided legitimate ID cards for transgender clients that matched their chosen name and gender presentation.

“When I saw the movie about Christine Jorgensen’s sex change, I thought, ‘Oh, my God, that’s what I am—that’s who I am,'” says Elizondo, referring to a fictionalized film released in 1970 based on Jorgensen’s autobiography. “But if I could barely pay rent or buy food, how in the hell was I going to have a sex change? It was the farthest thing from my mind.”

Elizondo finally scheduled her gender reassignment surgery in 1974, when she was working for a telephone company in San Francisco. “I was originally going to be transferred to Sunnyvale, but they cancelled my transfer and I had to come back as a girl after working with my coworkers for three years as a boy,” she explains. “The telephone company had a letter from my doctor, and my supervisor told all my coworkers, ‘Felipe is not going to be Felipe any more.'” Shortly thereafter, many insurers, including Medicare, dropped coverage of procedures related to gender reassignment, which was only reinstated in the last few years.

“It was like opening a door and going through the other side, becoming a brand new person.”

In the late 1970s, the Harry Benjamin International Gender Dysphoria Association—now known as the World Professional Association for Transgender Health—developed guidelines for working with transgender patients known as the Standards of Care, and in 1980, Gender Identity Disorder (GID) was first included in the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic Manual. Although these steps improved access to care, they also pathologized transgender identity, making it difficult to access treatment without a formal diagnosis. As Stryker writes, “Far too often, access to medical services for transgender people has depended on constructing transgender phenomena as symptoms of mental illness or physical malady, partly because ‘sickness’ is the condition that typically legitimized medical intervention.” (It’s worth noting that some people who identify as transgender desire no medical interventions, while others opt for surgery to help alleviate their experience of gender dysphoria.)

While trans advocates were working for better healthcare, a larger and more powerful LGBTQ political movement was forming. A few years after the riot at Compton’s, the cumulative experience of repeated clashes with police and city officials paved the way for a more organized approach, which activists deployed at the Stonewall Inn in New York: When the Stonewall riots began in June 1969, queer activists were ready for an event that could unify their movement in cities throughout the U.S.

Sociologists Elizabeth A. Armstrong and Suzanna M. Crage pointed out a number of attributes that made Stonewall more resonant than earlier conflicts between the police and LGBTQ communities in a 2006 article for the “American Sociological Review.” “Street queens and hustlers—marginalized by class, gender-presentation, and often race—were more willing than others to confront police, and were important in the riots at both Compton’s and the Stonewall Inn,” Armstrong and Crage write. “What Stonewall had, and Compton’s did not, were activists able and willing to capitalize on such rioting: high-resource, radical gay men.” Well-connected activists ensured there was plenty of media coverage of the Stonewall riot, and as community members rallied the neighborhood and outsiders came to witness the upheaval, the protests were drawn out over multiple days.

Trans erasure was rampant in media coverage of the early “Gay Liberation” movement, as seen in the New York Times coverage referring to thousand of “young men and women homosexuals” at the first annual Stonewall march held in 1970.

East Coast homophile activists, including those who had organized the conservative Annual Reminder protest in Philadelphia, decided to hold a yearly event in New York in honor of Stonewall and encouraged other cities to stage their own protests at the end of June. Although some West Coast homophile groups resisted celebrating the Stonewall riot because of its association with unruly behavior that antagonized police, they grudgingly recognized the power of a national day of protest. Often called “Christopher Street Liberation Day” (named after the location of the Stonewall Inn), the annual festivities continued to grow, eventually transforming into the international LGBTQ Pride celebration we know today.

The 1972 program cover for San Francisco’s first annual LGBTQ Pride parade, which organizers called “Christopher Street West” to evoke the location of the Stonewall Inn.

In many ways, the commemoration of Stonewall represents a culmination of the movement rather than its initial catalyst, with the riot at Compton’s being one of many stepping stones toward police and legal reform. But as Stonewall’s reach spread, its foundational story drowned out a more complicated narrative of collective queer resistance, downplaying the importance of police confrontations in other places. The push to unify LGBTQ people within a single movement also meant prioritizing certain struggles over others, like the efforts to legalize same-sex marriage rather than outlawing discrimination toward trans people in healthcare, housing, and employment.

As a result, stories of the original Stonewall riots have often been distorted to highlight white gay men while pushing gender-nonconforming folks out of the picture. “They often portray Stonewall as a gay man’s riot, but it wasn’t,” Elizondo says. “It was everybody, including queens like Sylvia Rivera and Miss Major. I know it wasn’t only the trans community that fought back at Gene Compton’s Cafeteria; it was everyone. We all put our lives on the line to be who we are today—people got raped, thrown in jail, and murdered. We were all fighting for the same thing, the right to be treated equally.”

Despite the community’s increasing visibility, transgender people still face enormous hurdles toward acceptance. Today, transgender Americans have a much higher likelihood of depression and attempted suicide than the general population, often stemming from social stigma, bullying, and violence, as well as biased healthcare practices. Gender-nonconforming people are also more likely to be homeless or living in poverty because of legalized discrimination in housing and hiring, while LGBTQ+ youth are at an even greater risk of social isolation and depression.

Eventually, Elizondo built a career with non-profit organizations like Project Open Hand, Shanti, and the San Francisco LGBT Community Center, and in 2015, she was honored as a Lifetime Achievement Grand Marshal for San Francisco Pride. “I’m sure there were a lot of riots that we don’t know anything about because they weren’t publicized,” Elizondo adds. “But my goal is to make sure that our history here in San Francisco is not forgotten.”

The cover of Vanguard Magazine, Volume 1, Issue 9, from 1967. Courtesy of the Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Transgender Historical Society.

(For more information on transgender history, check out Susan Stryker’s film “Screaming Queens: The Riot at Compton’s Cafeteria” and her book, Transgender History. For an in-depth exploration of the Tenderloin, read Gary Kamiya’s piece “Arise Tenderloin.” Visit San Francisco’s GLBT History Museum for in-depth exhibitions on the city’s queer roots.)

The Struggle in Black and White: Activist Photographers Who Fought for Civil Rights

The Struggle in Black and White: Activist Photographers Who Fought for Civil Rights

Singing the Lesbian Blues in 1920s Harlem

Singing the Lesbian Blues in 1920s Harlem The Struggle in Black and White: Activist Photographers Who Fought for Civil Rights

The Struggle in Black and White: Activist Photographers Who Fought for Civil Rights Before Rockwell, a Gay Artist Defined the Perfect American Male

Before Rockwell, a Gay Artist Defined the Perfect American Male Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

For those interested in learning more about the life, work and legacy of Dr. Magnus Hirschfeld, we have an exhibition opening at the GLBT History Museum in San Francisco this Friday (August 19) that will feature scarce historical materials from my collection:

http://www.glbthistory.org/2016/07/20/new-exhibition-honors-gay-movement-pioneer-dr-magnus-hirschfeld/

This is a wonderful story. For those interested in learning more about the Tenderloin’s over two decades as the geographic center of SF’s GLBT movement, see my book, The Tenderloin: Sex, Crime and Resistance in the Heart of San Francisco.

New Yorkers sometimes boast, “Only in New York,” mostly because they have few references outside the city. So your focus on the Compton riot was as welcome as your attention to the efforts of the Mattachine Society, which protested during the McCarthy era, when far more homosexuals lost their jobs than communists. As someone with two old boyfriends into drag—and leather, not so surprisingly—your stories and profiles brought back many late nights in the world of performers, gossip, and glamour at The Trio cafe, where Waylon Jennings and Madame used to hang out.

Although estimated at less than .3% of population, the right of even 1 transgender person to be free in this most profound expression of self brings them into the fight of the LGBT movement as a second T. As we become a convenient political bloc, it’s vital to discredit the notion that gender is some fluid dynamic isolated from sexual characteristics. You’ve got to know that queens will be fabulous whether or not boys are given dolls as toys.

This fluid gender doctrine, proposed by John Money of Johns Hopkins, is gospel to gender feminists wishing to vanish physical and mental differences between men and women. It asserts that nurture overrides nature in determining sexual identity and so, fosters erroneous psychological and physical assessments of traits inherent to transgender people.

Money proclaimed his study a successful proof that sex was determined by cultural and societal training, despite contradiction by the horrific and tragic outcome for its subjects, Bruce and Brian Reimer. You can learn more about the irreparable harm and deceit Money perpetuated on the twins and the world at large in the BBC documentary and article links following:

https://m.youtube.com/watch?t=0h0m0s&v=MUTcwqR4Q4Y

https://www.pop.org/content/deconstruction-gender

I love love love your articles, but may I suggest you update some language? Assigned male/female is much better than male/female-bodied. The latter is a problem because it still suggests penis=man, vagina=woman. Every woman is female-bodied by definition, regardless of what that body looks like. <3

Thanks for the suggestion Maggie; we’ve just updated the piece. :)