When I was kid in the 1980s, I assumed everything I knew about Christmas had existed since the beginning of time. So it was strange to grow up and realize that only 10 percent of my concept of Christmas came from ancient history—the story of Jesus’ birth, the myth of a winter gift-giver leaving treats in footwear, and the transposing of the Nativity story onto pagan traditions such as putting up an evergreen tree. Another 30 percent of my Christmas beliefs were just 160 years old, specifically, the story of a heavyset man in a fur-trimmed suit who made wooden toys in a North Pole workshop year-round and then, on Christmas Eve, traveled the globe on a reindeer-led sleigh, sliding down chimneys and putting presents into stockings.

“Moms were, and still are, the hidden architects of Christmas, doing the unseen labor to make the magic happen.”

In fact, the majority of the Christmas traditions I feel nostalgic for were created very recently, just after my parents were born—everything from the warm Bing Crosby songs, the blow-mold light-up Santas, and the starburst ornaments to the competitive outdoor light displays and the base of the tree piled with mountains of gifts wrapped in shiny, patterned paper and bows. This is the Christmas most of us still experience today, a relatively new phenomenon, mostly conceived and codified in the wake of World War II.

The invention of modern-day Christmas and all its shimmering accoutrements are explored in Sarah Archer’s new book, Mid-Century Christmas: Holiday Fads, Fancies, and Fun from 1945 to 1970. Over the phone from Philadelphia, Archer shared with me how the Santa Claus myth was adapted in the 1950s to soothe Cold War fears about space travel and nuclear weapons, as post-war prosperity led to an explosion of Christmas consumerism and a retreat into traditional gender roles. She also explained how we ended up with aluminum trees, cellophane craft projects, a televised Yule log, and “A Charlie Brown Christmas.”

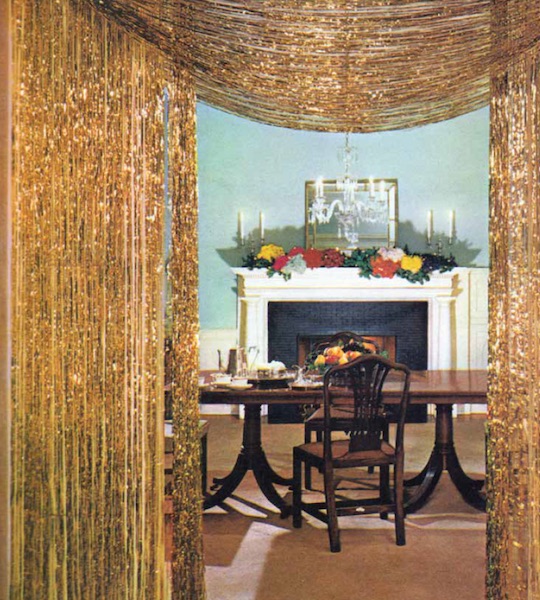

Top: A happy housewife can’t believe the abundance of Christmas presents she sees in an 1960s ad for Reynolds Metals foil gift wraps. (From Mid-Century Christmas, reproduced with permission from Reynolds Consumer Products) Above: Gold tinsel curtains adorn the entry to a dining room in the December 1961 “House Beautiful.” (From Mid-Century Christmas, reprinted with permission of Hearst Communications, Inc.)

Collectors Weekly: How does Mid-Century Christmas relate to Christmas 2016?

Sarah Archer: As I was writing the book, the presidential election was weighing heavily on my mind. It was so disturbing to hear the rallying cry to “Make America Great Again.” We know that factory jobs in this country have declined because of automation not immigration, but there’s an emotional attachment to the idea of Americans making lots of stuff like they did in the 1950s. That was an era when Americans believed in projects—like the Space Race—that were bigger than ourselves, and when we relied on, rather than shunned, facts in order to understand the potential of our new technologies. All I could think was, “God, it would be so great if people wanted to revive that aspect of the 1950s, instead of Jim Crow.”

Collectors Weekly: It’s fascinating that all of our ideas about Christmas seem to begin in either the 19th century or the post-World War II era.

Archer: It’s also super weird that this is not widely known. The Puritans who first settled America were opposed to celebrating Christmas. It wasn’t until the 19th century that Christmas became popular in America, when it transformed from an adult holiday to a child-centered one. During the Victorian era, the drinking, carousing, and harassing of rich people, which had been the hallmarks of a traditional Christmas, were replaced by shopping. In Stephen Nissenbaum’s book, The Battle for Christmas: A Social and Cultural History of Our Most Cherished Holiday, he republished a wonderful small-town newspaper op-ed from the early 1830s, warning Americans that our children could become spoiled due to all this frippery and consumerism. This is only 10 years after Christmas as we know it today was invented, and people were already like, “Oh my goodness, it’s become terrible and commercial!”

The December 1961 “House Beautiful” featured a white Christmas tree in an elegant, beige Modernist room. (From Mid-Century Christmas, reprinted with permission of Hearst Communications, Inc.)

Collectors Weekly: How was Christmas about nostalgia for Victorians?

Archer: The Industrial Age was deeply scary to people. Today, living in big cities, we’re used to smog and loud cars, and pollution is regulated. But imagine living in a period when, all of a sudden, factories started to dot your once-bucolic landscape and pump foul smoke into the air. As the agrarian economy fell away, doing a day’s work meant laboring in horrible, scary conditions, amid machines that seemed like science fiction. It was traumatizing. Victorians responded by creating the Arts and Crafts and Gothic Revival movements, which idealized the work of the craftsman.

By the time Santa Claus was invented in the 1800s, he was already colluding with the department stores; Santa was all in with the new capitalism. But he was depicted as working in his North Pole workshop, using simple hand tools to make sturdy wooden toys. Santa’s image was very wholesome, he didn’t operate factory machines or a blast furnace, and he rode in a sleigh, not a train. He was totally Arts and Crafts.

Assorted Shiny Brite ornaments from the 1950s and 1960s, shown on a vintage aluminum Christmas tree. Photo by Jeffrey Stockbridge. (From Mid-Century Christmas)

Collectors Weekly: How did Christmas-tree ornaments originate?

Archer: Originally, Europeans hung apples on fir trees. Apples are fruit that comes into season in the fall and winter, and they are red and shiny, so they contrast nicely with the green tree. The idea of making them out of glass goes back to the late Renaissance in Germany. It’s a neat idea—a piece of fruit that never goes bad.

“Santa Claus was reinvented as a space traveler. Instead of looking at the sky and thinking it’s a scary place, you could picture Santa flying through the atmosphere.”

The Christmas market as a whole was dominated by Germany until the 1930s. European decorative arts makers—everything from metal workers to glass blowers to paper makers—had the monopoly on fine craftsmanship. If you were wealthy in America, you would buy your fine china from France or Germany. But at the start World War II, the blockade of Germany was imposed, and Americans couldn’t import glass ornaments.

In the late 1930s, Max Eckardt, a German immigrant who had been importing ornaments, approached F.W. Woolworth’s about making ornaments in the United States. Together, they reached out to New York-based Corning Glass Works, the maker of Pyrex, to see if its equipment could be adapted for glass ornaments. Corning ended up using a machine designed to blow glass light bulbs to make ornaments, which Woolworth’s sold under Eckhardt’s trade name, Shiny Brite.

A dozen Shiny Brite ornaments, including some ombré ones, from the 1950s and 1960s, shown in a vintage box from the same period. Photo by Jeffrey Stockbridge. (From Mid-Century Christmas)

Originally, Shiny Brites were just round, but then Corning came up with more and more complex shapes. By mid-century, you started seeing what they referred to as a “Sputnik style” ornament, which would have a bulbous part that tapered to a point. Corning made Santa Claus figures, animals, fruit, flowers, and sometimes abstract shapes that look like glass insulators. Shiny Brites were made mostly by hand because they were very delicate.

By the 1960s, Shiny Brites were being sold in their original solid colors, as well as in complex stripes and patterns. Color combinations included the traditional holiday palette of bright red and green, but there were also ornaments in cool hues, such as magenta and turquoise. I even have a few in my collection that are ombré.

Collectors Weekly: How did General Electric sell people on the idea of decorating the outsides of their homes with holiday lights?

Archer: The company had opened a research campus called Nela Park in East Cleveland, Ohio, “Nela” being an acronym for National Electric Lamp Association. There, GE started putting on a Christmas light show in the 1930s, pioneering the concept of outdoor lighting. Nela Park’s displays were like Christmas cards come to life, a dazzling display of ingenious electrical decorating. GE published tons of how-to guides that showed people how to build apparatuses for the outside of their houses, so they could, say, create the illusion of a Christmas tree that was three-dimensional.

Inspiration rom the 1963 “GE Christmas Lighting and Decorating Guide.” (From Mid-Century Christmas, reproduced with permission from GE Lighting, a business of General Electric Company.)

Collectors Weekly: How did World War II change how people celebrated Christmas?

Archer: During the war, companies like Hoover would take out print ads saying “We’re not selling vacuum cleaners right now. All our machinery, equipment, and resources are going to the war effort. Buy a new vacuum after the war.” It’s hard for me to imagine a company doing that today, taking out an ad to say, “We’re not selling anything.” There was a palpable sense, at least on paper, that everybody was in the war effort together. Thanks to rationing, people focused on improvising and doing without, and that left its mark on that generation forever.

The do-it-yourself Christmas projects started with the Depression. Magazines of the era had a lot of advice about how to celebrate Christmas despite a lack of supplies. In the 1940s, you see the same concepts in the women’s magazines but for different reasons. You couldn’t bake because sugar was being rationed, so the articles would explain all these workaround MacGyver solutions. In terms of Christmas decorations, it was suggested that you use soap to make it look like there’s fake snow on your tree. You could use pine cones and other things from nature to make wreaths or ornaments. Despite the postwar abundance, these traditions carried well into the 1950s and ’60s. In a late ’50s “Better Homes and Gardens” magazine, I found a great spread on “decorating with nature’s gifts,” using shells and twigs. Those ideas were being marketed, not to crafty hippie-dippy hipsters but to regular housewives through mainstream magazines like “Women’s Day.”

A geometric tree made from greenery found outdoors was described in a December 1956 “Better Homes and Gardens” spread called “Decorate with Nature’s gifts.” (From Mid-Century Christmas)

Collectors Weekly: All the songs I consider “good” Christmas songs are from World War II.

Archer: It was a Golden Age of Christmas Songs. Many of them have a tinge of longing about what will happen when the servicemen return home and how everything will be better. When Baby Boomers look back that era and its music, there’s a bittersweetness baked into the nostalgia.

These recordings made Christmas more part of pop culture, more Hollywoodized. Before that point, people sang very traditional carols, hung traditional decor, and traded old-fashioned cards. But in the ’40s, you start to see movies in which Christmas shopping and decorating is part of the plot, like “Miracle on 34th Street” or “Christmas in Connecticut,” whose main character is like a proto-Martha Stewart figure. These films loosened the veil covering the machinery behind the holiday. “White Christmas” was the same thing. Such movies took a bit of the mystery out of Christmas, but they also made the holiday more culturally potent.

Handmade ornaments you could make with your kids featured in the December 1956 issue of “Better Homes and Gardens.” (From Mid-Century Christmas)

Collectors Weekly: Why was crafting with your children still so important after the war ended?

Archer: In the ’50s and ’60s, Americans focused on education and inculcating creativity, thanks to generalized Cold War anxiety. We felt we needed to build a population of future scientists and engineers to keep up with the technology of the USSR. Educational play, as you see in 1950s children’s museums and ’60s toys, focused on science. Even the crafting piece of it—which was also a way to reinforce domestic coziness and the nuclear family ideal—was a tool to inspire inventiveness. The idea of kids helping with Christmas decorating flourished after the war. Materials that we derived from the war effort, like the plastic used to make Tupperware, replaced glass and metal in a lot of products. That made decorations and tools safer for kids to handle.

“A lot of mid-century Christmas items came from thinking about repurposing a material produced for the military.”

Similarly, major corporations looked at their war innovations and tried to adapt them to the peacetime market, which is where we get things like Reynolds cellophane wrap and Scotch tape. Aluminum, for example, loomed large in defense manufacturing, because it was light and strong, the perfect material for building airplanes. After the war ended, aluminum manufacturers had to figure out how to keep selling their products. To some extent, aluminum foil is a useful kitchen staple, but how much foil are housewives really going to buy?

The main aluminum producer, Alcoa, published two books that gave women ideas for all the craft projects and decorating they could do with their kids using foil. It’s what I would call the 1950s and ’60s version of content marketing, in line with the creative thinking that was typical of the age. It was a way for companies to make new products, like Reynolds cellophane wrap, not just a household staple for covering up casseroles, but also an art supply. Reynolds published crafting pamphlets that would arrive in the mail, get inserted into magazines, or were sold with products when you bought them. If you scour Etsy and eBay, you can find wonderful examples from Alcoa, Reynolds, DuPont, and 3M pamphlets, with articles like “You can decorate your house with Scotch tape for the holidays with a little ingenuity.”

The 1965 “Christmas Magic” gift-wrapping guide put out by the 3M Company gave suggestions for decorating your home and presents with Scotch Brand Tapes. (From Mid-Century Christmas, used with permission)

Collectors Weekly: The images we have of Christmas are largely male figures—Santa Claus, Frosty the Snowman, and Jesus. But according to your book, mothers rule Christmas.

Archer: Moms were, and still are, the hidden architects of Christmas, doing the unseen labor to make the magic happen. Women do the most Christmas shopping and decorating. They do the at-home holiday activities and craft projects with kids. They plan and host the Christmas parties and gatherings. Actually, the 1947 movie “Miracle on 34th Street” does a good job of emphasizing the importance of women. To some extent, so does the Victorian novel, “Little Women.”

Collectors Weekly: How did science and technology become enmeshed in Christmas in the mid-century?

Archer: In the postwar period, the Christmas nostalgia for times of yore is fused with “Jetsons”-era futurism that embraces high-tech toys and spaceships. It was a way of trying to integrate that cozy, domestic Christmas feeling with new technology. In the 1950s, the big American worries were the threats from USSR, including getting into a nuclear war and the implications of the Soviet space program. Would Americans be spied on from space? Are there aliens? Those fears seem quaint now because we’ve had 50 years get to get used to the idea of space exploration. For people who had come through the Depression and the war, though, it must have been pretty mind-blowing to see the United States suddenly sending men into space.

That’s why Santa Claus was reinvented as a space traveler. Instead of looking at the sky and thinking it’s a scary place, you could picture Santa flying through the atmosphere. There was a powerful desire on the parts of designers, marketers, and retailers—the main stakeholders if the Christmas industrial complex—to help people get used to new technologies. Santa, the icon of coziness, was their messenger, often presented in an amusing way.

In the 1950s, Santa ditched his sleigh for a rocket ship, as seen on the cover of Dell’s December 1959 “Santa Claus Funnies,” published by Western Printing & Litho Company. (From Mid-Century Christmas)

Collectors Weekly: Which brings us to NORAD. When did the Defense Department start to “track” Santa?

Archer: That phenomenon originated with a misprint in a local newspaper. I’ve Googled this and researched it and read a couple different sources, including “The New York Times.” The story sounds apocryphal, but apparently, it’s true. A department store bought a newspaper ad for its Santa hotline in 1955, but accidentally misprinted the number, so that it rang a CONAD (Continental Air Defense Command) center. At first, the person who answered the phone thought, “What on earth is this?” But then someone at CONAD had the bright idea to use the mistake to market the warm and fuzzy side of the military, and suggested they start doing the annual tracking of Santa Claus, which was taken over by NORAD (North American Aerospace Defense Command) in 1958. As far as I know, they’re still doing it, but it’s now available online.

An ultra-Modern Christmas tree of candle holders and starbursts was shot for the December 1961 issue of “House Beautiful.” (From Mid-Century Christmas, reprinted with permission of Hearst Communications, Inc.)

Collectors Weekly: How did new atomic technology influence mid-century Christmas imagery?

Archer: After the U.S. military deployed the atomic bomb in 1945, the government found it difficult to explain to laypeople how it worked, so the Atomic Energy Commission developed molecular illustrations to educate the public. Then, graphic designers, furniture makers, clock designers started using highly stylized versions of that visual language. You see spiky silhouettes with balls on the end or orbit-like ovals in all kinds of consumer goods—from chandeliers, lamps, and clocks to the legs of coffee tables. The signs and roof lines of Googie-diner architecture were meant to suggest and evoke a sense of orbital movement. The predecessor to the Atomic Space Age style was 1930s Streamline Moderne, where things like vacuum cleaners were designed to look as sleek and futuristic as cars and trains. In the 1950s, you had the ancient custom of a fir tree with apples hanging off of it converted to an aluminum tree bedecked with glass spheres, which often looked like an illustration of a molecule. You can see the look of the Atomic Age in wrapping-paper patterns, too.

The abstracted Christmas-tree pattern on this mid-century wrapping paper has a molecular look to it. Circa 1940-1959, made by the Crystal Tissue Company. Gift of Christopher and Esther Pullman. Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum/Art Resource, New York. (From Mid-Century Christmas)

In the ’20s and ’30s, wrapping paper tended to be kitschier, like patterns of Scottie dogs wearing scarves. In the ’50s and ’60s, you started to see many more abstracted holiday patterns that had that Atomic Age look. The wrapping paper would have starburst patterns that were faintly or overtly holiday-related, with a similar color palette and degree of design sophistication that you might find in Mid-Century Modern upholstery or fashion fabrics.

Collectors Weekly: Was everything about mid-century Christmas trendy and future-focused?

Archer: I interviewed Richard Wright, who founded the auction house Wright 20, for a Slate piece I wrote about the “Masters of Sex” décor a few years ago. In real life, Dr. Masters lived in a regular Colonial Revival red-brick house in St. Louis, but on the show, they had him living in this Mod-style house. The producers did that deliberately, to visually position him as a man of science. Richard said there’s this belief, because our media landscape today is so in love with the Eameses, Florence Knoll, and the “Mad Men” aesthetic, that everybody in the ’50s was living in the Eero Saarinen-designed TWA terminal.

The fact is that most people kept the same floral upholstered sofas they always had, living in more of a “Leave It to Beaver” milieu than a hip Mod one. So, if you put up an aluminum tree, that was a way of dipping your toe into Modernism. You might have a completely traditional house like my grandparents did, but you might add one wacky new-fangled thing, and Christmas was definitely the time of year when it was OK to try something like this out. You didn’t have to move into a Neutra house, but you could try an aluminum Christmas tree.

This image from a 1960 Alcoa Aluminum newsletter shows a family pulling the tubes off the branches of an aluminum tree and then decorating it with ornaments. Via Alcoa Records, Detre Library & Archives, Senator John Heinz History Center. (From Mid-Century Christmas)

The company that produced the most aluminum for the war effort was Alcoa, but there were also some smaller companies, too, many of which were based in Manitowoc, Wisconsin, of all places, which was one of the big aluminum capitals of North America. Like a lot of mid-century Christmas items, including the acrylic rubber that coats Christmas lights cords, aluminum trees came from thinking about repurposing a material produced for the military. The aluminum strips that were used to make the trees were originally designed for something called chaff, which was sprinkled over enemy territories to scramble radar because the little pieces of metal would diffuse the signal.

Many 1950s aluminum tree producers used Alcoa branding. The exterior of the box would say, “We proudly use Alcoa aluminum.” You could put ornaments on these trees, but one of the challenges of decorating them was not getting electrocuted, which was mentioned prominently in the how-to pamphlet that came with the tree. Because it was not safe to put electric lights on the metal, the companies distributing the trees would sell a rotating lamp that would shine different-colored lights on the tree to bathe it in magenta or purple.

The 1962 Spiegel Christmas catalog offered aluminum trees as well as rotating lamps to bathe them in color. (From Mid-Century Christmas)

Collectors Weekly: There’s so much nostalgia for aluminum trees, but how prevalent were they?

Archer: It was a pretty short-lived fad. I think when the aluminum tree emerged in the mid-1950s, it was such a wacky novelty that it was hard for people to resist. And then in the ’60s, it became deeply uncool. In the book, I have an image from a ’70s episode of “The Bob Newhart Show” that features an aluminum tree, but my sense is it was meant to be deliberately kitschy. The aluminum tree is an interesting example of something futuristic quickly seeming old-fashioned. In the 1950s, people took a real comfort and delight in the artificial, which the hippie movement subsequently rejected. You see that same rejection of artifice in 1965’s “A Charlie Brown Christmas.” The newfangled and fake is clearly positioned as bad. The wholesome good tree is humble and natural, even if it looks kind of sad and pathetic.

In 1965’s “A Charlie Brown Christmas,” Charlie and Linus look at their weather-beaten natural tree in front of yellow and pink Christmas trees that likely represented the fake aluminum trees of the day. CBS Television animated special, directed by Bill Melendez. Photofest, Inc. (From Mid-Century Christmas)

Collectors Weekly: How did the G.I. Bill affect our Christmas traditions?

Archer: The G.I. Bill offered mortgage assistance, business loans, and college tuition funds to returning veterans. In particular, home ownership was thought to be a mark of stability and a way to create wealth. Quickly, the G.I. Bill, along with other social forces, converged to create a market for the Levittowns, the nation’s most famous new tract houses. It followed that these new homeowners would see their homes as an important part of their new identities. Holiday decorating became a part of that.

But it paints an incomplete picture to say that the postwar era was a boom for everybody. People of color absolutely did not benefit from the G.I. Bill in the same way white people did because they couldn’t get access to the same kind of loans, or they would be turned away from housing in desirable neighborhoods. It was the upwardly mobile white people moving to the suburbs who became the target demographic for the booming Christmas industry.

A listing of the various outdoor holiday lights General Electric offered in 1963 in “GE Christmas Lighting and Decorating Guide.” (From Mid-Century Christmas, reproduced with permission from GE Lighting, a business of General Electric Company)

Collectors Weekly: Did the increase in homeowners in the ’50s and ’60s help popularize Christmas light displays?

Archer: More people were in the suburbs and could decorate outdoors, for sure. That Nela Park outdoor-tableau idea from the 1930s flourished after the war, in part because fewer people were living in apartments and more people had houses with lawns. And they weren’t just living on a farm but on a cul-de-sac with lots of neighbors, so they weren’t decorating in isolation. People were in close proximity to one another, which meant everyone could see your display. Depending on the neighborhood you lived in, outdoor décor might be something you felt like you absolutely had to have.

Collectors Weekly: What forces were colluding to convince people they needed more stuff?

Archer: Communism was a unique threat to America—it was, by definition, anti-capitalist. If you were trying to prove that your capitalist way of life was better, the first thing you needed to do was buy more stuff.

“Was this the point of winning the war? Isn’t there more to the holiday than buying dishwashers when there are still people who are hungry?”

When people started living cheek by jowl alongside suburban neighbors in similar houses, they could see that the neighbors had a new car or new grill. It created that element of keeping up with the Joneses: If you didn’t get one, your neighbors might think you’re poor. The ease of obtaining credit and the relative boom in employment translated into buying power for middle-class people, something we’ve lost today. Things were cheap relative to how much extra cash people had on hand. Department stores developed intense marketing campaigns around goods providing a sense of identity. “Are you a modern person? You need Eames furniture.”

It’s hard to unwind the 2016 brain and imagine how the ads looked to people at the time. If you were in your 30s and it was 1955, everything you had grown up with either looked Victorian and shop-worn or an imitation of Art Deco style. To be confronted with bold, geometric, primary-colored furniture was mind-blowing. After the war, the idea of becoming a new kind of person was very tempting, as it represented a lot of novelty and excitement. There was a huge spike in spending on things like dishwashers, refrigerators, and anything you can imagine related to the home—new carpets made of nylon fibers, furniture with flame-retardant upholstery.

Kitchen appliances were hot gifts to put under your aluminum Christmas tree in the postwar era. This Reynolds Metals ad flaunts both. (From Mid-Century Christmas)

Collectors Weekly: The first bank charge cards appeared in the late ’40s, and the first plastic interbank credit cards launched in 1966. How did those influence Christmas?

Archer: Oh, yes, the joy of credit cards! The expansion of access to credit paralleled the boom in homeownership, shopping, and decorating in the ’50s and ’60s. Before credit cards, certain department stores would offer store credit or let you buy things on layaway, so you didn’t pay all at once. Credit cards were a new way to buy everything at once and not worry about paying for it until later, which bolstered the Christmas market.

Beyond the instant gratification they provided, credit cards put the feeling of upper middle-class shopping into the hands of people who had never had it, for better or for worse. If your tradition had been that every kid got one toy at Christmas, maybe now it was five toys per kid, and you could spend even more money on decor. The credit card gave people license to live large in a way they hadn’t before.

The cover of the 1958 Sears Christmas “Wish Book” shows off the beautiful ornaments of the era. (From Mid-Century Christmas)

Collectors Weekly: What was the impact of the Sears Christmas ‘Wish Book’?

Archer: I’ve talked to a lot of people for whom the arrival of Sears Christmas catalog was a big event, and as kids, they would obsess over the toys. In the 1950s, you had cartoons appearing on television for the first time, meaning the Boomers were the first generation of children who were exposed to advertising designed specifically for them. That was enormously powerful. For parents who let their kids watch TV in the house—or let their kids read the Sears “Wish Book”—their goose was cooked, and they did what they had to do to give their kids a happy Christmas.

But what about Santa? “If you’ve ever wondered how the good things under your tree were made and delivered in time for a merry Christmas morning, the last thing you might think of is a battery of busy IBM machines,” reads a 1960s ad for IBM. (From Mid-Century Christmas, reprint Courtesy of International Business Machines Corporation, ©International Business Machines Corporation.)

Collectors Weekly: It’s interesting, though, how the big mid-century Christmas TV specials for kids rejected commercialism.

Wrapping paper, “Star of Bethlehem,” circa 1940-’59. Gift of Christopher and Esther Pullman. Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum/Art Resource, New York. (From Mid-Century Christmas)

Archer: Yes. They promoted the notion that commercial side of Christmas is not the real holiday. An interesting thought exercise is to compare “The Grinch” narrative, which first appeared in 1957 as a picture book, to the Scrooge in “A Christmas Carol.” The Grinch character is loosely based on Scrooge. Both tell stories of a grumpy guy who has an awakening and then everything’s cool. But the epiphany each has are total opposites. Scrooge’s awakening is all about abundance, giving people food, money, and presents, while the Grinch is taught that all that stuff doesn’t really matter. The accouterments of Christmas are great fun, but they don’t give the holiday its meaning.

At the peak of the Industrial Revolution in Britain in the 1800s, Charles Dickens was confronting new levels of wealth and inequality in Great Britain. In 1957, Ted Geisel, known as Dr. Seuss, was writing about consumerism and looking at the ways people were living and focusing their attention on material abundance. He asked, “Was this the point of winning the war? Isn’t there more to the holiday than buying dishwashers when there are still people who are hungry?”

“A Charlie Brown Christmas” and “The Grinch” are similar in that way. They both look at this holiday, in 1964 and 1957 respectively, and ask, “What does it mean to celebrate this holiday as Americans? What does it mean to have all these resources, and what should we do with them?”

Collectors Weekly: How did the televised Yule log come about?

Archer: In Scandinavia, the ancient festival of Yule was the Northern European Saturnalia, the pagan holiday that got woven into Christmas. The idea is that everything is temporarily dead or covered with snow, but you have fire and food and brightly colored things inside, which gives everybody a boost at that time of year. Burning a Yule log remained a beloved Christmas tradition for centuries.

In 1966, the New York City television station WPIX had a broadcast snafu when the regular Saturday college basketball broadcast was suspended, which could have resulted in dead air on Christmas Eve. One of the producers suggested, “What if we just film a Christmas fireplace?” And so they did. It was the fireplace at Gracie Mansion, the mayor’s residence when John Lindsay was in office, and the scene was set to “easy listening” Christmas music by artists like Percy Faith and Nat King Cole. It was so popular, WPIX aired it every Christmas Eve through 1989, and it spawned imitations across the United States. You can find vintage newspaper ads announcing the times “The Yule Log” would be on. To me, it’s the perfect complement to the aluminum tree or the glass Christmas ornament, in which you take the analog original and re-create it in a manufactured way. Today, you can find versions of “The Yule Log” online and on digital cable. I was at a Christmas party not too long ago where somebody projected a Yule log video onto the wall with an LCD projector. People loved it. There’s something about it that’s so absurd, but strangely, the power of the fireplace is still hypnotic, even when it’s fake. It’s like, “Let’s stare at this for a while.”

“Let Cellophane add glamour to your Christmas” declares a 1949 ad for DuPont. Via Hagley Museum and Library, Wilmington, Delaware. (From Mid-Century Christmas)

Collectors Weekly: How have the visual representations of Christmas changed since the Vietnam War?

Archer: After the Vietnam War, the United States economy was in a recession. The immediate future didn’t live up to the promise of the post-World War II era. After the giddy optimism that was palpable in 1950s, the U.S. had a string of horrible assassinations and civil unrest. Once you lived through 1968, how could you be enthusiastic about a “Jetsons”-style vision of the future? It wasn’t happening.

“Only 10 years after Christmas as we know it today was invented, and people were already like, ‘Oh my goodness, it’s become terrible and commercial!'”

By the time I was a kid in the 1980s, Santa Claus appeared totally medieval, not futuristic at all. Back then, the Space Age stuff of the 1950s and ’60s was considered very out-of-date. There was plenty of commentary about how noncommercial and “pure” Christmas “used to be,” but Christmas has been about shopping since Victorian times.

Today, we have a lot of anti-shopping, anti-computer screen, anti-gadget rhetoric around the holidays. At the same time, we love our smartphones and flat-screen TVs. Predictably, around Christmastime, you can read plenty of op-eds about how you should focus on experiences rather than things. But do we really crave something simpler? It’s almost as though we want to have the tiny-house version of Christmas, with everything streamlined and minimal. It’s an interesting commentary on our relationship with stuff.

In the end, I think the way we observe Christmas merely reflects the world around us. This Christmas, many celebrations will probably have social-justice elements to them. Even people who are not religious may be looking to Christmas as a chance to reflect on what it means to be an American.

Paul Rand illustration for El Producto Cigars, “Santa’s Favorite Cigar,” offset lithograph on paper, 1953-57. Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum/Art Resource, New York. Photo by Matt Flynn. (From Mid-Century Christmas)

(To learn more about Christmas in the Cold War era, pick up Sarah Archer’s book, “Mid-Century Christmas: Holiday Fads, Fancies, and Fun from 1945 to 1970.” If you buy something through a link in this article, Collectors Weekly may get a share of the sale. Learn more.)

The War on Christmas Cards: Dead Robins, Used Paperclips, and Other Secular Greetings

The War on Christmas Cards: Dead Robins, Used Paperclips, and Other Secular Greetings

Losing Ourselves in Holiday Windows

Losing Ourselves in Holiday Windows The War on Christmas Cards: Dead Robins, Used Paperclips, and Other Secular Greetings

The War on Christmas Cards: Dead Robins, Used Paperclips, and Other Secular Greetings Will the Real Santa Claus Please Stand Up?

Will the Real Santa Claus Please Stand Up? ChristmasCollectible Christmas items range from antique hand-crafted pieces like blo…

ChristmasCollectible Christmas items range from antique hand-crafted pieces like blo… Mid-Century ModernMid-Century Modern describes an era of style and design that began roughly …

Mid-Century ModernMid-Century Modern describes an era of style and design that began roughly … Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

These are great. My cousin-in-law, James Lileks, author of Interior Desecrations and The Gallery of Regrettable Food, and lileks.tumblr.com/ would have a field day with these images. Check him out!

Great article – very comprehensive and informative!

I’m glad somebody likes Christmas.

I was born in ’38 and I just hated it until I got old enough to ignore it.

Such a shame that the author had to inject her politics into this interview in the very first paragraph.

Chris is triggered, haha.

This is a terrific article!

I absolutely loved the article but so disappointed about the political unnecessary personal comment,what a shame.Hard to enjoy the article for reflecting on the comment.

Lucky to have been born in the golden age of innocence still. Christmas is still about Christ, better to give than receive and you try to keep the spirit of Christmas with all the year long. What a wonderful gift we are given if just accept His ever loving grace and ask Him to come into our hearts.

Very enjoyable article. Too bad the author interjected her political thoughts. Understandable as this gives her some liberal woke points in the fake news media.

Merry Christmas

This is the best article, or anything in printed form for that matter on where Christmas, as we knew/know it, came from. WWII. I kept thinking that there’s something about the 50’s with the emergence of the middle class. This article is PERFECT! Many blessings to you for writing and posting this!!

I’m not seeing this interjection of politics….?