In an essay for her 1977 series “On Photography,” Susan Sontag wrote that “photography has become almost as widely practiced an amusement as sex and dancing, which means that, like every mass art form, photography is not practiced by most people as an art.”

Yet today, found or “vernacular” photographs are increasingly presented as art objects, a reverence reinforced by the steady transition from analog to digital technology. These visual time capsules attract us with their physical beauty and their captivating narratives, inspiring everything from print publications like Found Magazine to blogs like Look At Me. Even the most successful digital photo apps, like Instagram, mimic the authentic quality of vintage photographic prints, down to their faded colors and unexpected blemishes.

“The idea of someone scratching out the face of an adult says something very powerful to me.”

Few vernacular photographers considered their work a creative pursuit; for most it was simply a form of documentation. “Birthday parties, weddings, funerals, new cars, moving into the new house, holidays, and vacations. These are times that the camera came out,” says St. Louis-based collector and folk-art scholar John Foster.

During the early 20th century, as ordinary people learned to take photographs, discarded prints became a necessary by-product of the camera’s democratization. “In a sense, the American people documented the 20th century themselves,” says Foster. “There are millions and millions of these pictures, these artifacts of the 20th century.”

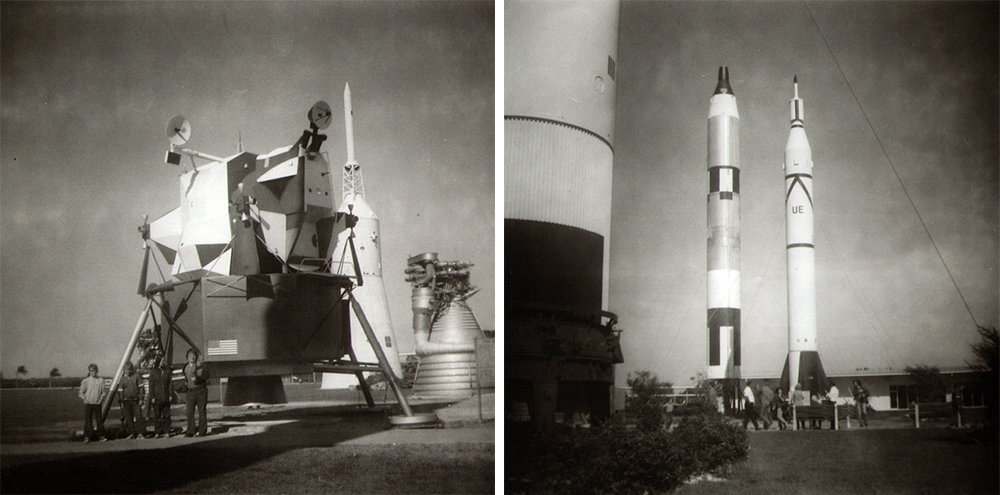

Top: John Foster enjoys the unintended humor of found photos, like this shot of two suburban women with a massive scythe. Above: Images taken at Kennedy Space Center in Titusville, Florida, with a Brownie Hawkeye camera found by Chris and Grace Hughes.

For Foster, the simplest description of his collection is “all the other photography,” meaning any image that wasn’t intended as artwork. Beyond amateur family snapshots, the genre also includes photojournalism, mug shots, crime-scene documentation, x-rays, and other everyday photographs that weren’t destined for the gallery wall.

Although the images in Foster’s collection weren’t originally created as art, he only chooses those which meet his particular aesthetic standards. In the late 1980s, Foster discovered a photo that opened his eyes to the beauty of vernacular imagery.

“It was a portrait of two people standing in front of a fence, and you could see over the fence into a housing complex or something, with the grandmother looking over the fence. Then even further back, someone’s in the window. They were all perfectly posed and arranged in a way that I knew was not intentional, but they’re photo-bombing this image in a really wonderful way. I’ve always loved things that happen unintentionally, accidentally.”

Eventually, Foster adopted the name Accidental Mysteries for his blog and weekly Design Observer posts after the fortuitous magic found in the ephemera of earlier eras. As explained in an essay on his website, “a sign produced 75 years ago, intended to simply give direction, today may suggest new meanings to viewers informed by postmodernist critical thinking … reflecting a kind of magical power that certain objects have to reinvent themselves.”

Foster regularly features images from his personal collection on his blog and in museum exhibitions, pushing viewers to reconsider these seemingly ordinary photos. “I’ve seen people look at them with great fondness and interest, people that are not necessarily artists. And the reason they do is because they’re drawn to the particular photo style of the day, like the cut of the deckled edge or a particular photo color, something that they remember. It’s this familiarity with the everyday image that draws them to it so closely. It might be a birthday party of anonymous people, and they love the fact that they’re anonymous, that it could be found for 50 cents in a bin somewhere.”

A vacation scene from a roll of film in a Brownie Hawkeye camera found in St. Jacobs, Ontario. Courtesy Chris Hughes.

This physical nature of vintage photographs is an important part of their appeal, especially in our modern digitized world. Foster tells the story of a friend who purchased an extra hard drive to have more storage space for the thousands of digital photos on his computer, despite the fact that only a handful of the images had ever been printed and enjoyed as physical photographs. “It dawned on me that the 21st century might be the most documented but least saved,” says Foster.

“It dawned on me that the 21st century might be the most documented but least saved.”

The love of analog photography also inspires camera collectors Chris and Grace Hughes, who founded the Toronto photo studio A Nerd’s World. The Hugheses’ collection of found film, which they’ve shared on Show & Tell, started as a side effect of their search for vintage cameras. “Film photography is disappearing, and it’s only a matter of time before it’s completely gone,” explains Chris. “What we’re trying to do is sustain a little bit of that culture when we buy these old cameras. I don’t know how to explain it, and it sounds a little corny, but we feel like memories are handed down with a camera. It feels like we’re bringing someone new into the family, and it’s become an addiction.”

For years, the couple saved any film found with their camera purchases in a plastic bag in their fridge, and only about a year ago did they decide to develop a roll. The film was taken from an old Brownie they bought in Pennsylvania, and the printed photos showed a group of young people on a road trip in the U.S., probably during the 1940s. They were hooked.

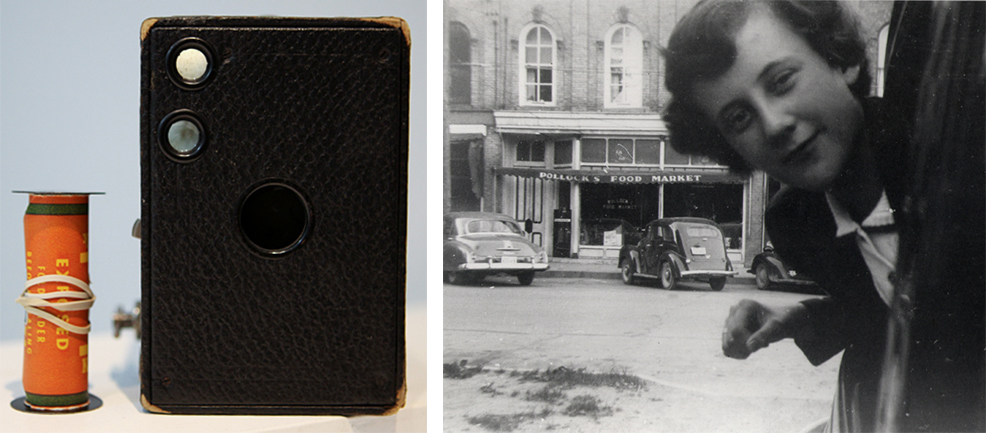

This box Brownie contained negatives from a possible roadtrip, including the image on the right. Courtesy Chris Hughes.

Now, when the Hugheses go on thrifting expeditions, they specifically check for cameras still loaded with film, most of which indicate this using a small red dot on the back. If they already own the camera model, dealers often offer them the undeveloped film free of charge (though the Hugheses typically purchase the camera anyway to keep it together with its enclosed film). “Without us, the next person that bought the camera would probably just toss out the film,” says Chris.

Portrait of a lady and her plant, from film found by the Chris and Grace Hughes in a Kentucky antiques shop.

The Hugheses hope to revive the spirits of these photographic relics by showing them to the world, and they’re not alone. “Last Saturday,” says Chris, “a woman donated 50 vintage cameras because her father had passed away and she wanted them included with other cameras. It sounds weird that a camera has a personality, but we feel that they do, and that they’re happier together, either displayed or being used, and not just sitting in a box somewhere.”

Part of the Hugheses’ gallery is now devoted to showcasing prints from their found film, which captivate visitors. “You’re seeing real pictures, real time, real color. It brings back your personal memories, as well,” says Chris. “With digital photos, that unique quality is not there. There’s no excitement when you take a picture and see it instantly. Whereas with film, it’s like opening a Christmas present when you print them for the first time.”

For John Foster, this sense of authenticity is heightened for photos that have been hand-altered or personalized to express joy, excitement, or anger. “When I find a photograph with faces that have been scratched out, or that someone decided to hand-color, those are just extra bonuses for me. The idea of someone scratching out the face of an adult says something very powerful to me. It’s like they want them out of their life completely.”

Chris also loves the photographs that leave questions in a viewer’s mind, like the images he and Grace discovered of two girls with what appears to be a three-legged horse. “But even the simplest of pictures excite me,” says Chris.

While the Hugheses’ search is compelled by the thrill of mystery, Foster is focused more on aesthetic qualities. “I don’t collect photographs for their historical value or for any particular subject matter,” says Foster. “I’m not out looking for Victorian ladies or images of boats on the ocean. I’m always looking for the great image.” Having studied fine arts through graduate school, he’s well aware of the art-historical context for found photography, particularly in the larger field of folk art.

Two girls posing with a horse that appears to have only three legs. Courtesy Chris Hughes.

For Foster, a print’s history is far less important than its visual beauty and the response it inspires. “It doesn’t really mean anything to me, who shot the image,” says Foster. “But when I do find an image that’s one of the best, I just flip out about it. I like thinking that it could be a Lee Friedlander or a Diane Arbus or a Henri Cartier-Bresson.”

Years of photo-hunting have helped Foster train his eyes to recognize an interesting composition among the thousands of snapshots at flea markets and antique shops. “I’ll pick up a handful of a hundred, and I flip them like a deck of cards, because I can tell that quickly whether they have any intrinsic visual power at all or not,” says Foster. “Out of a hundred, I might find a single one that’s even a maybe. That goes to show you how many average, boring, mundane, same height, same scene, same everything is repeated in these old images.”

The image at left reminds Foster of Depression-era photographs taken by Dorothea Lange, while the one on the right is reminiscent of Alfred Stieglitz’s work. Courtesy John Foster.

“But if a snapshot ends up in my collection,” Foster continues, “it’s a lucky day, because it’s kind of like a dog that gets rescued from the pound. It was all scruffled and hungry and abandoned, but now it’ll be happy and healthy and loved.”

In contrast to vintage prints, it might seem like rolls of forgotten film are few and far between, but the Hugheses think there are plenty still out there. “It seems like it would be hard finding a roll of film after 65 years sitting in the camera, but there are so many cameras,” explains Chris. “People pass away, and their grandkids are given these cameras, and they donate them to a thrift store or end up at a garage sale. And that’s where we step in.”

The most unique photographs in the Hugheses’ collection are far from the mundane snapshots of smiling children and family vacations; they depict the carnage and devastation of World War I. Chris and Grace acquired these photos at a pre-estate sale, where bids are placed without the option of inspecting the goods. After their bid for a Richard Verascope camera was accepted, the Hugheses opened the apparatus to find nearly 50 stereoscopic prints on glass slides inside. Used to simulate a three-dimensional view, these slides show wartime scenes of barren trenches, ruined villages, and fallen soldiers.

A barren landscape seen in a stereoscope slide from the Hugheses collection taken during World War I.

“When you look through an antique stereoscope viewer,” explains Chris, “it’s a thousand times better than a digital scan. They give me shivers, looking at them. They’re definitely my favorite find.”

The dramatic appeal of wartime photos contrasts sharply with the lighthearted qualities of other vintage photographs, particularly those that unintentionally provoke a laugh. “Humor is a big part of my life,” says Foster, “and I really love it if I can find that built-in humor in a snapshot. Now, that story can be whatever you make it up to be; I’m not going to try to force it or tell you what it is.” Despite his appreciation of an interesting visual narrative, Foster says he’s never met any of the photographers or subjects of his photos, and doesn’t intend to seek them out.

The somber tone of these images from a Yashica-A is heightened by their tragic backstory. Courtesy Chris Hughes.

The Hugheses didn’t expect to learn about the subjects of their photos either, but the publicity from a recent article in the Toronto Star changed that. Following the story’s publication, the couple was contacted by someone who recognized a young boy in one of their photographs. “When I called the gentleman,” explains Chris, “he didn’t want to be publicly interviewed; he wanted to remain anonymous. But he said, ‘This is not a hoax. I’m certain that is my uncle.’ He told me the boy died a tragic death, and he didn’t want the story brought back into the newspapers.”

Though this is a particularly poignant example, in reality all found photos are a reminder of absence, a moment we never experienced. As Sontag suggests, “All photographs are memento mori. To take a photograph is to participate in another person’s (or thing’s) mortality, vulnerability, mutability. Precisely by slicing out this moment and freezing it, all photographs testify to time’s relentless melt.”

(Special thanks to Chris Hughes and John Foster for permission to print their photographs.)

Who's That Kodak Girl? Early Camera Ads Depict Women as Adventurous Shutterbugs

Who's That Kodak Girl? Early Camera Ads Depict Women as Adventurous Shutterbugs

Like Iggy Pop? Thank Your Grandparents

Like Iggy Pop? Thank Your Grandparents Who's That Kodak Girl? Early Camera Ads Depict Women as Adventurous Shutterbugs

Who's That Kodak Girl? Early Camera Ads Depict Women as Adventurous Shutterbugs Unusual Suspects: Finding the Humanity in Vintage Mugshots

Unusual Suspects: Finding the Humanity in Vintage Mugshots PhotographsFrom Mathew Brady's Civil War photos to Ansel Adams' landscapes to Irving P…

PhotographsFrom Mathew Brady's Civil War photos to Ansel Adams' landscapes to Irving P… Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

You can see something special in each one. A certain feeling they give off. The one of the city street in the snow is a real art piece that I would love to have enlarged and framed for my walls. Beautiful.

I always ejoying looking at shots like these. Found film / prints are such a mystery, and have so much to give. This was a great article.

What a wonderful article!

There is something about old photographs, unperfected by modern technology, that makes me feel like I am connecting with something REAL.

Thank you very much Collectors Weekly for a great article. My wife (Grace) and I are grateful, and we still spend every Sunday looking for “found film”

All the best,

Chris A. Hughes

A Nerd’s World

a really lovely collection. I love old photos and they are after all someone’s memory captured, even if as an artist shot. It is like little bits of others minds.

The maze picture is beautiful, I love pictures showing the back of people as it leaves more to the imagination as to why the picture was taken or if the person in the shot deliberately turned away.

I love looking at black and white photos. These images are beautiful yet creepy at the same time. I just recovered some family photos that date back as early as the early 1900’s.