Soda’s reputation has fallen a bit flat lately: The all-American beverage most recently made headlines due to an FDA investigation of a potential carcinogen, commonly called “caramel coloring,” used in many soft-drink recipes. This bit of drama follows other recent stories that paint an unflattering picture of the soda industry, including New York’s attempt to ban super-sized drinks, the eviction of soda machines from many public schools, and a spate of new soda-tax proposals. All these regulations are designed to mitigate the unhealthy impacts of Big Soda, such as increasing childhood obesity, in the same way restrictions were slapped on cigarettes in years past.

“The drink became symbolic of America, and even freedom in a way. It made Coca-Cola more than just another fizzy drink.”

Faced with all this bad press, it’s hard to believe that the “evil” soft drink actually began as a health product, touted for its many beneficial effects. In fact, soda got its start in Europe, where the healing powers of natural mineral waters have been prescribed for hundreds of years. Bathing or drinking the water from these natural spas was thought to cure a wide variety of illnesses. Tristan Donovan, the author of Fizz: How Soda Shook Up the World, says that the ailments treated with bubbling spring waters constituted a “ludicrously big list,” everything from gallstones to scurvy. (In reality, the beverage did little more than settle an upset stomach, without any adverse side effects.)

Despite the broad appeal of mineral water, packaging and transporting this effervescent liquid proved difficult, so chemists set out to make their own. “It took until 1767 for the real breakthrough to happen when Joseph Priestley, the British chemist who was the first to identify oxygen, figured out a way to put carbon dioxide into water,” says Donovan. Priestley’s process used a fermenting yeast mash to infuse water with the gas, resulting in a weakly carbonated drink. Proponents of the bubbly beverage’s healthful properties were thrilled.

Top: A Coke advertisement from 1907. Above: Early soda machines required oversized cranks to manually carbonate water, like these devices from the 1870s.

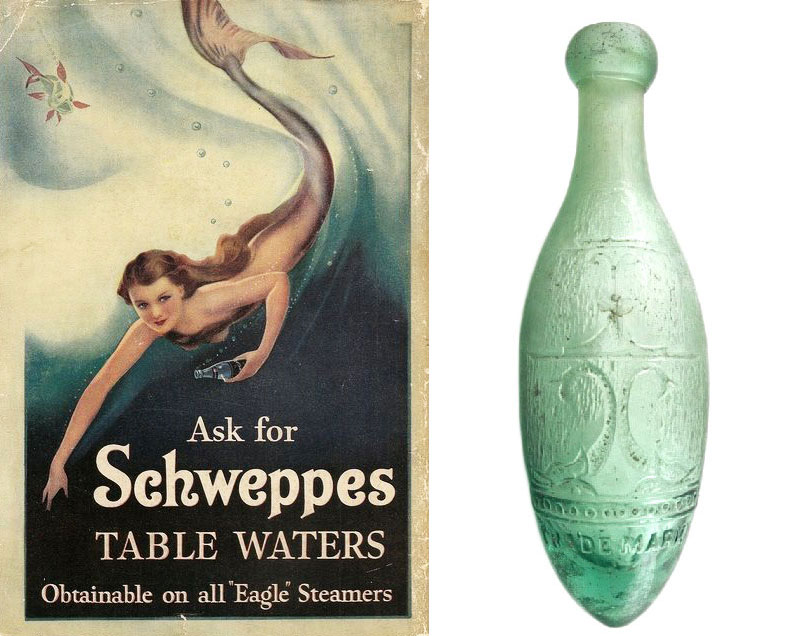

In 1783, the Swiss scientist Johann Jacob Schweppe improved on Priestley’s process with a device for carbonating water using a hand-cranked compression pump, launching the now-famous Schweppes company. Yet it was still virtually impossible to get carbonated water to market without losing its fizz, as drinks in corked stoneware bottles tended to go flat quickly and glass bottles weren’t widely available. Charles Plinth solved part of the problem with his soda syphon in 1813, which could dispense bubbly water without compromising the remaining mixture’s carbonation, though syphons still had to be refilled at a facility that actually produced the carbonated liquid.

Finally, in 1832, the English-born American inventor John Matthews developed a lead-lined chamber wherein sulphuric acid and powdered marble (also known as calcium carbonate) were mixed together to generate carbon dioxide. The gas was then purified and manually mixed into cool water with steady agitation, creating carbonated water. Matthews’ design worked either as a bottling unit or a soda fountain, since it produced enough carbonated water to last customers all day. But America’s weak glass industry still wasn’t able to support large-scale bottling plants, so the simplest way to sell soda water was at public fountains.

Left, a Schweppes ad from 1937, more than 150 years after the mineral water company was founded. Right, early carbonated waters were sometimes sold in rounded “torpedo” bottles, forcing them to lie flat so the liquid contents would dampen the cork, preventing it from shrinking.

“If I were going to single out one person as creating the carbonated drink industry, I would give credit to Benjamin Silliman, even though he eventually failed financially,” says Anne Funderburg, the author of Sundae Best: A History of Soda Fountains.

An illustration of a French soda water apparatus, featuring soda syphons and carbonating machines below the counter, circa 1830s.

“Silliman was a chemistry professor at Yale College, and he wanted to supplement his small paycheck while also doing something altruistic for mankind. Silliman believed that carbonated waters could be used as medicine, so he set up a business in New Haven, Connecticut, selling bottled carbonated water.” Though Silliman had little success selling the drink at his local apothecary, he decided to expand his business, designing a larger-capacity carbonation apparatus and securing investments to open two pump rooms in New York City.

In 1809, Silliman started selling his soda water at the Tontine coffeehouse and the City Hotel, elegant establishments that catered to an elite clientele (the Tontine was in the same building as the New York Stock Exchange). In addition to their supposedly beneficial products, these early soda fountains were designed to create an uplifting environment, adorned with marble counters and ornate brass soda dispensers. However, Silliman continued to focus on the medical benefits of his soda water, while his competitors recognized that the social aspects of drinking were potentially more appealing.

In their heyday, soda fountains were elaborately designed places for rejuvenation. Left, the counter at the Clarkson & Mitchell Drugstore in Springfield, Illinois, circa 1905. Via the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum. Right, an 1894 ad for an ornate fountain produced by Charles Lippincott & Co.

“People who had better business sense than Silliman set up their pump rooms like a spa: You came to drink your carbonated water, but you hung around reading the free books and conversing with other intelligent people who were also there to drink carbonated water,” says Funderburg. “They understood that you could make a real business out of it, where Silliman treated soda more as a medicine.” Though the servers at Tontine recognized that customers preferred soda water as a mixer, it remained a slow seller, and eventually Silliman was forced out of the industry. Even as Silliman’s company failed, the soda trend was catching, and successful fountains soon popped up in other cities like Philadelphia and Baltimore.

Because carbonated water was still viewed as a health drink, the first soda shops were situated in drugstores and closely linked with their pharmacies. “Part of the reason they became so entwined is that the process of carbonating water and making syrups or flavorings was something pharmacists already had the skill set to do,” Donovan explains. “They were the obvious people to take this on, and they started adding in ingredients they thought were health-providing. Sarsaparilla was linked to curing syphilis. Phosphoric acid was seen as something that could help hypertension and other problems.” Long-standing favorites like ginger ale and root beer were also initially prized for their medicinal qualities.

According to Darcy O’Neil, author of Fix the Pumps, pharmacists initially used sweet-tasting soda flavors to mask the taste of bitter medicines like quinine and iron, as most medication was taken in liquid form during this era. Plus, many pharmaceutical tinctures and tonics were already mixed with alcohol, which made even the most pungent medicinal flavors enticing. “Many of the elixirs and tonics contained as much alcohol as a shot of whiskey,” writes O’Neil. “This was popular with both the imbiber and pharmacy. The imbiber could get an alcoholic drink at a fraction of the bar’s price because there were no taxes on alcohol-based ‘medicine.’”

Acid phosphates like Horsford’s, seen in these advertisements from the 1870s, gave many soda fountain drinks a distinctively tart flavor.

Besides booze, sodas of the 19th century also incorporated drugs with much stronger side effects, including ingredients now known as narcotics. Prior to the Pure Food & Drug Act of 1906, there were few legal restrictions on what could be put into soda-fountain beverages. Many customers came to soda fountains early in the morning to get a refreshing and “healthy” beverage to start their day off right: Terms like “bracer” and “pick-me-up” referred to the physical and mental stimulation sodas could provide, whether from caffeine or other addictive substances.

Pharmacists were soon making soda mixtures with stronger drugs known as “nervines,” a category that included strychnine, cannabis, morphine, opium, heroin, and a new miracle compound called cocaine, which was first isolated in 1855. “Cocaine was a wonder drug at the time when it was first discovered,” Donovan explains. “It was seen as this marvelous medicine that could do you no harm. Ingredients like cocaine or kola nuts or phosphoric acid were all viewed as something that really gave you an edge.

“Cocaine was a wonder drug at the time when it was first discovered. It was seen as this marvelous medicine that could do you no harm.”

“Recipes I’ve seen suggest it was about 0.01 grams of cocaine used in fountain sodas. That’s about a tenth of a line of coke,” he says. “It’s hard to be sure, but I don’t think it would’ve given people a massive high. It would definitely be enough to have some kind of effect, probably stronger than coffee.” While the dosages were small, they were certainly habit-forming, and soda fountains stood to profit from such consistent customers.

Throughout the mid-19th century, soda fountains spread clear across the U.S., and a niche health drink became a beloved American refreshment, capable of competing with the best cocktails in the world. Soda throwers or soda jerks, as they were later called (after the jerking arm movement required to operate the taps), had to be just as skilled as bartenders at mixing drinks; in fact, many bartenders started working at soda fountains once the industry was booming.

“Around that time, it became obvious to the medical profession that there weren’t any health benefits to carbonated water on its own, so people started selling it as a treat,” says Funderburg. “It’s hard to put our heads around how much of a treat cold fizzy water was back then. People didn’t have mechanical refrigeration, so to have a cold drink was a big deal. They flavored them with chocolate or fruit syrups, and citrus fruits like lime and lemon became favorites.”

By the early 20th century, soda fountains were an integral part of neighborhood drugstores, such as this counter in the People’s Drug Store, in Washington, D.C. pharmacy, circa 1920. Via Shorpy.

Presumably, as soon as carbonated water was commercially available, people were adding their own flavorings to spice things up. “The earliest advertisement I’ve managed to find for something we would call soda was from 1807, and that was a sparkling lemonade being sold in York,” says Donovan. “It could have been a fairly new idea, but people had flavored still water for years beforehand.”

Lemon drinks made up the first of many flavor fads to hit the soda industry, likely because un-carbonated lemonade was a familiar refreshment. According to O’Neil, lemon syrups were already used as a base flavor for many medicines, so concocting a tasty drink with these was natural. Beyond lemon, all manner of citrus-flavored sodas were enjoyed in the mid-1800s, in part because their essential oils were easy to extract and preserve. Other fountain staples included orange, vanilla, cherry, and wintergreen, although shops were always testing new recipes looking for the latest hip drink. Most soda mixtures were made using a sugary simple syrup, but popular flavors were often far more tart than today’s sodas.

One of the most complete records of these innovative cocktails is DeForest Saxe’s 1894 book entitled Saxe’s New Guide, or, Hints to Soda Water Dispensers. In its pages, Saxe illuminates his own experience working a soda fountain, detailing tips for pouring sodas, keeping them cold, and making an extensive list of drink recipes. From a “Tulip Peach” to a “Swizzle Fizz,” or an “Opera Bouquet” to an “Almond Sponge,” Saxe covered the wildest new flavor sensations in addition to the classic egg creams and flavored phosphates. But despite their fantastic names, Saxe’s recipes notably avoid the medicinal ingredients many soda fountains relied upon to give their drinks a kick.

By the turn of the 20th century, many Americans had begun to recognize the dangers of serving unregulated medications in such a casual manner. In 1902, the Los Angeles Times published an article titled “They Thirst for Cocaine: Soda Fountain Fiends Multiplying,” which focused on the questionable ingredients in popular drinks like Coca-Cola. However, Donovan says that judging from the small quantities of cocaine in actual recipes, it’s doubtful that there were many soda-addicted fiends.

In fact, Coke was developed while looking for an antidote to the common morphine addictions that followed the Civil War: Veteran and pharmacist John Stith Pemberton concocted the original Coca-Cola mixture while experimenting with opiate-free painkillers to soothe his own war wounds. The company’s first advertisement ran on the patent-medicine page of the Atlanta Journal in 1886, and made it clear that Coca-Cola was viewed as a health drink, “containing the properties of the wonderful Coca plant and the famous Cola nuts.”

Of course, these were also the properties of your basic uppers: Cocaine is a coca leaf extract, and the African kola nut is known for its high caffeine content. Once the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906 required narcotics to be clearly labelled, the majority of Coca-Cola’s cocaine was removed, though it took until 1929 for the company to develop a method that could eliminate all traces of the drug.

However, at the turn of the 20th century, the harshest public criticism was reserved for a different devilish drink—alcohol. As temperance groups rallied against booze, they helped propel teetotaling customers into American soda fountains. In 1919, the year before Prohibition took effect, there were already 126,000 soda fountains in the United States, far exceeding the number of bars and nightclubs today. “Soda had always played up the temperance link,” says Donovan. “Even before Prohibition, sodas like Hires Root Beer were presented as non-alcoholic drinks and marketed that way. Lots of fizzy-drink companies encouraged the temperance movement, and they were generally quite pleased from a business perspective when Prohibition came in. Their sales rose. People couldn’t go to bars anymore so they turned to soda fountains instead.”

Bottled soda sales were also booming as companies increasingly marketed their drinks for home consumption. The crown cork, a predecessor to today’s familiar bottle cap, was invented by William Painter in 1892, finally improving sanitation and solving leakage issues with earlier corked bottles. “The bottle cap really sealed the deal, because before that the process was quite difficult and the stoppers weren’t particularly secure,” Donovan says. “Even though they could produce and fill bottles en masse, keeping them clean and the seals strong proved quite tricky. Essentially, the bottle cap was the invention that allowed bottles to get past their reputation of being faulty containers that exploded or had insects and dirt slipping into them at the factory.”

Though Coke had established a major soda-fountain presence by the late 1890s, the company’s long-term success depended on getting their drink into bottles. “At the time, Coca-Cola didn’t really like the idea of bottled drinks,” explains Donovan. “They thought bottles were dirty, and setting up bottling plants and distribution networks was very expensive, so they were better off just shipping their syrup around.” But in 1899, two entrepreneurs named Joseph Whitehead and Benjamin Thomas convinced Coca-Cola co-founder Asa Griggs Candler to give them the exclusive rights to bottle his product. Coke would soon become the greatest success of the bottling movement.

Instead of building their own bottling facilities, Whitehead and Thomas came up with a more clever solution—selling franchises to regional bottlers all over the country. “They divided the U.S. up into small territories and sold Coca-Cola bottling licenses to all these local businessmen. This meant that the company didn’t have to put any money into this huge expansion. Their biggest competitor at the time, Moxie, refused to do this and, ultimately, got left behind,” says Donovan. Additionally, Moxie’s flavor was much more tart than Coke’s, making it an outlier as mainstream sodas came to depend on more sugary recipes.

Left, early Coca-Cola ads, like this one from 1905, emphasized its energizing medicinal effects on the mind. Right, in 1921, the company promoted its soda fountain drinks with ads that outlined the best way to hand-craft a Coke.

By the end of the 1920s, more Coca-Cola was sold in bottles than served at fountains. And over the next decade, the repeal of Prohibition combined with America’s growing car culture to hasten the demise of the ubiquitous pharmacy soda fountain. “When roadside stands like Dairy Queen started opening up after World War II, they were taking customers away from soda fountains,” says Funderburg. “Americans were spending a lot of time in their cars and moving to the suburbs, so most of the drugstores on Main Street were in decline. Soda fountains were also labor intensive, while retail was moving to a self-serve model.”

The final step in Coke’s global expansion occurred during World War II, when the company declared that all American troops should have access to a bottle of Coke for 5 cents. By aggressively expanding abroad and using creative methods to deliver their products, like pop-up soda fountains, the company made good on its promise. “Obviously, that made the U.S. troops very loyal to them, but it also made Coca-Cola iconic around the world,” says Donovan. “At the end of the war, in the bombed-out cities of Europe where food was in short supply, one of the things first you might see was U.S. troops—these well-fed heroes who helped liberate you—carrying bottles of Coca-Cola. The drink became symbolic of America—and even freedom in a way. It made Coca-Cola more than just another fizzy drink.”

During the 1940s, Coca-Cola built soda fountains in far-flung locations in order to serve its drinks directly to American troops, like at this fountain in the Philippines.

Our thirst for carbonated drinks clearly didn’t evaporate along with soda shops: Instead, consumers turned to the convenience of bottled beverages, as Big Soda took over from locally crafted drinks. Following the war, many Americans purchased their first home refrigerators, further bolstering the market for bottled sodas. After being forced to remove their narcotic ingredients, sodas increasingly relied on sugar to hook their customers. And as the soda giants continued to grow, these companies tweaked their recipes to lower overall costs, turning to cheaper ingredients like corn syrup and caramel coloring.

“Coca-Cola, Dr. Pepper, Pepsi, and Moxie all started out as soft drinks that were supposed to have some medical benefit,” says Funderburg. “Nobody worried about sugar in the late 19th century. That was an era when people wanted to be plump; women were supposed to be full-figured back then. Certainly, no one worried about their weight the way we do today.”

Along with new policies that restrict where sodas are sold, our growing awareness of soda’s unhealthy impact is hurting soda sales. Although the carbonated soft drink remains a remarkably American beverage (we consume around 13 billion gallons a year, or a full third of global sales), statistics show a decline in American soda purchases over the last few years. At the same time, bottled artisanal sodas have made a comeback everywhere from Whole Foods to corner bodegas. Even a few authentic soda fountains have opened in recent years to re-create the complicated drinks of yore, like Blueplate in Portland, Oregon, Ice Cream Bar in San Francisco, or Franklin Fountain in Philadelphia.

Through 1950, the ingredients for 7UP included lithium citrate, a mood-enhancer—this ad is from the 1930s.

“There’s definitely a soda movement that seems to be echoing the shift toward craft beer,” says Donovan. “People are trying to use more local, natural ingredients in contrast to the big, monolithic brands. There’s a push to make soda more real again, rather than this overprocessed, industrial thing.” Only recently have studies begun to show that sugars can be just as addictive as drugs like morphine and cocaine, making sweeteners one of the industry’s greatest challenges.

“Sugar or any kind of sweetener is quite crucial to the flavor of these drinks. Artificial sweeteners got tainted, possibly wrongfully, by their link to carcinogens. So soda has been struggling with the fact that people are distrustful of artificial sweeteners, and—let’s be frank—they don’t taste as good as sugar. The soda industry’s approach is putting a lot of faith into finding natural sweeteners that taste just as good as sugar and have no calories in them. It could be quite a game changer if they do.”

Regardless of whatever “healthy” new recipes these companies come up with, if history is any measure, they’ll probably turn out to be terrible for you.

Treasures of the Corner Drugstore and Soda Fountain

Treasures of the Corner Drugstore and Soda Fountain

Beer Money and Babe Ruth: Why the Yankees Triumphed During Prohibition

Beer Money and Babe Ruth: Why the Yankees Triumphed During Prohibition Treasures of the Corner Drugstore and Soda Fountain

Treasures of the Corner Drugstore and Soda Fountain How Snake Oil Got a Bad Rap (Hint: It Wasn't The Snakes' Fault)

How Snake Oil Got a Bad Rap (Hint: It Wasn't The Snakes' Fault) Mineral and Soda Water BottlesBottles for mineral and soda water first appeared in the late 1600s. As a g…

Mineral and Soda Water BottlesBottles for mineral and soda water first appeared in the late 1600s. As a g… PharmacyThe neighborhood drugstore, featuring a soda fountain and lunch counter, be…

PharmacyThe neighborhood drugstore, featuring a soda fountain and lunch counter, be… CokeFrom its invention by John S. Pemberton in 1886 to today, Coca-Cola has bec…

CokeFrom its invention by John S. Pemberton in 1886 to today, Coca-Cola has bec… Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

WOW, you have captured the whole Carbonated Water History…took me half an hour to read whole of it, awesomeness, how long did it take to write you is the question, lol…

One thing in the history of colas should mention Sir Francis Richard Burton who in? came up with a cola elixer recipe during his travels in South America. Thx for the nice article.

Coke has committed more than $30 Billion to international expansion. So the saga continues.

Quinine, or tonic, water would fit this category as a treatment for malaria. Thus was invented by the British colonials in tropical climates the gin and tonic as a way to make more palatable the daily dose of quinine required to fend off the disease.

Nicely done, GREAT article! =)

An entertaining and enlightening article. Very well done, thanks.

I believe there was an old, maybe 1912, silent movie about a product called “Dope-a-Coke” – – a soda which addicted & ruined the inventor’s son??

Inevitably politics crept into the mix – Coca Cola’s availability during the second world war was a double-edge sword as they paid congressmen handsomely to lock up wartime sugar supplies to continue production, thus forcing competitors out of business. Pepsi bottlers and others relied on bootleg shipments of sugar to keep the doors open, paying other officials to overlook the irregularities and middle-of-the night truck traffic.

Loved the visuals in this article! I think you were on the right track when you covered “acid phosphate” drink Horsford’s, but then you got off on a tangent about drugs like cocaine and opiates etc. My point is that people are mineral deficient leading to degenerative diseases. One of these minerals is phosphorus which is supplied by colas like Horsfords and Coke. So if people would drink only the cola syrup without all the sugar and caffeine in modern soft drinks, they would benefit. Phosphorus is not a drug, its a nutrient.

I would’ve liked to have had a Bracer for my Monday Mornings. The only thing this article leaves out is Sodas insidious connection to the fast food industry.

how can you have this whole article and not mention Vernors ONCE?? It is dated for 1880 way before coke pepsi and dr. pepper

Wonderful article. I knew carbonated water was medicinal. The story of carbonated water is a familiar story that can be applied to many situations in our economy today. It started off as a good thing and was turned into a bad thing. Lots bring back the wisdom of all things gone industry. Industry is the new dinosaur.

Dr. Pepper bottles and cans used to (many still do) have the symbol in a sort of clock icon that shows a “10-2-4” on the labeling. The times of 10am, 2pm, and 4pm, were the times of day that workers (factory workers) were supposed to stop what they were doing and have their Dr. Pepper soda pick-me-ups to get them through the day! If Dr. Pepper had cocaine in it, back in the day, then I’m sure, even at 0.01 milligrams of cocaine, that it was a great reason to stop, and that it probably did give workers a however, small and brief, very effective to factory production “pick-me-up!”

So, from now on, daily at 10-2-and-4, stop and think of the multitude of past factory workers, who all had smiles on their faces at 5 min after 10, 2, and 4, and go on to lament the large amounts of caffeine that you are consuming just to get you through your own modern work day in comparison! *lol*

Very interesting article, thanks. My family was the owner of C. and H. Rosenstein Soda and Mineral Water of New Haven and I found out they sold out to Cott Soda sometime in the early to mid 1900’s so this was very interesting to learn about the origins of my ancestors’ industry.

Does Schweppes use acid phosphate in their soda water any more?

As a kid in a remote area I once found a ‘white rock’ bottle on my way to school. I always wanted to drink White Rock’ whatever but never had a chance.

I sometimes think some soft drinks today still have underappreciated qualities which could be beneficial if they weren’t made with so much sugar and corn syrup. Specifically root beer.

Was the trend of “Hot soda” drinks ever present during this time as part od health remedy of carbonation drinks?