In the near future, when books are looked upon as objects of pure nostalgia, the concept of a bookplate might need a bit of explaining: Before the reign of e-books, streaming content, and information stored in a mythical “cloud,” people stockpiled hardcovered paper objects full of written words. Of those educated persons who maintained personal libraries of their favorite tomes, the more affluent sometimes commissioned unique, artist-designed bookplates, which were affixed inside the book’s cover to make its allegiances clear.

“I’m a rich person, this is my property, and you’d better not take it.”

Books aren’t quite an endangered species yet, and the Association of American Publishers reports that sales of physical books are actually on the rise. Nevertheless, many who consider themselves avid readers have still never seen a bookplate in person—which makes sense, considering the trend peaked around a century ago. In fact, the use of bookplates started much earlier, with the oldest known plates dating to mid-15th-century Germany.

Until the printing press came along, all books were rarified manuscripts filled with calligraphy and illumination, painstakingly crafted by hand, and only the elite had access to them. In Europe, monasteries were one of the few places that people could handle literature they did not own, and according to Lew Jaffe, a bookplate collector for over 30 years, this created the need for the first known bookplates. “In monasteries that had libraries, they attached chains to the books so they wouldn’t be taken,” Jaffe explains. “But they also created hand-illustrated plates to paste into these books that essentially said ‘this belongs to such-and-such monastery or such-and-such rich person,’ and would include their coat of arms. It was like a warning: ‘I’m a rich person, this is my property, and you’d better not take it.’”

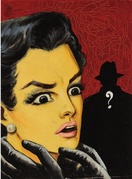

Top: A noir woodcut for journalist John Kobler, circa 1930s. Above: Left, the first-known bookplate, circa 1470s, was used in the books of Hildebrand Brandenburg of Biberach, which he donated to his monastery in Buxheim, Germany. (Via the Brandeis University Special Collections) Right, Pope Gregorio XIII’s bookplate crest from around 1572. (From the collection of Luigi Bergomi – click to enlarge.)

From its earliest days, the bookplate was a status symbol, expressing the individuality of a book’s owner as much as preventing theft. The European nobility who could afford their own private libraries adopted bookplates as one of many tools in their arsenal to remind others of their standing. Bookplates were also called “ex libris,” after the Latin phrase meaning “from the books of,” a phrase that was frequently incorporated into their design.

Name labels, like this design for Edward Bass, Jr., were a cheaper version of bookplates. (Image courtesy Lew Jaffe – click to enlarge.)

Jaffe explains that in the United States, early engravers who worked with fine silver and other metalware, like Paul Revere or Nathaniel Hurd, often designed bookplates as well. “If you’re into 18th-century American bookplates,” Jaffe says, “I suppose having George Washington’s bookplate or any of the designs by Paul Revere would be a holy grail.” Around the same time, some printers created cheaper book labels using lettering and basic borders for clients with less artistic aspirations. Name labels sometimes included a city, date, or favorite motto and could be easily mass-produced using a press with movable type.

In the late 19th century, the rising capitalist tides of the Industrial Revolution gave the bookplate new life as a badge of prestige for America’s nouveau riche. “Beginning in the 1890s, Americans were coming over to Europe and buying whole collections and libraries to bring home, though they probably didn’t even read those books—it was a show-and-tell kind of thing,” Jaffe says. “Americans, for the most part, didn’t have coats of arms, so they would hire an engraver, and the engraver would ask, ‘What design do you want?’ and they’d say, “Well, I have a pretty dog,’ or ‘I like to go fishing,’ or whatever. That’s how the more creative end of bookplate design really started. It was an affectation.” While most artists weren’t known specifically for their bookplates, Jaffe says that a few, like Edwin Davis French, did establish a reputation for their stunning ex libris engravings.

Like a carefully curated home library, the imagery of a custom bookplate spoke to a person’s favorite subjects, hobbies, or values. For creative types, bookplate designs might be executed by beloved illustrators or feature symbols of their chosen art forms, while labels for people of faith could incorporate religious symbols and those for sports fanatics could display their games of choice. Beyond Europe’s ubiquitous crests and coats of arms, other popular themes included ancient castles, ships sailing on the ocean, magnificent trees and landscapes, classical nudes, animals (especially cats), starry night skies, and, unsurprisingly, books.

Edwin Davis French was renowned for his bookplates. Left, a classical design for Edward Hale Bierstadt from 1894, and right, an underwater fantasy for W.K. Bixby from 1906. (Images courtesy Lew Jaffe – click to enlarge.)

Throughout the early decades of the 20th century, the mass production of paperbacks and increased literacy in the United States made books accessible to many more Americans than before. By the late 1920s, more middle-class Americans were building personal book collections and wanted to label them accordingly, though they couldn’t afford an artist-commissioned bookplate.

“Entrepreneurs rose to the occasion and created what we call ‘universal bookplates’ which are the kind you find in a stationery store today: There’s a box of bookplates with a pretty picture on them, and a blank where the name’s supposed to be. You’d either put your name in with a typewriter or pen, or you could have it printed in,” Jaffe says. Just as universal bookplates became accessible to less-affluent people, the popularity of personalized, artist-made designs also began to decline. Even so, artists like Rockwell Kent continued to receive accolades for their unique bookplate art.

A universal bookplate illustrated by Daniel Mitsui. (Image courtesy Lew Jaffe – click to enlarge.)

Jaffe is particularly interested in rare 18th-century American bookplates, as well as those that once belonged to famous people—whether actors, politicians, writers, or scientists. His collection already includes ex libris artwork belonging to figures such as J.P. Morgan, Sigmund Freud, Albert Einstein, and Cecil B. DeMille. “Bill Clinton uses a bookplate, and I’ve always wanted to get one,” Jaffe says. “A couple of years ago, when he was doing a book signing in Harlem, I waited about two hours and finally shook his hand. I really wanted to ask him about his bookplates, but I guess I was intimidated. Later, I wrote to Clinton and got a form letter back from a clerk without a bookplate. Maybe if I live long enough I’ll finally get one.”

If you’re interested in exploring the long history of bookplate design up close, many libraries and archives have bookplate collections, though most require some digging. “There’s only one public institution that has the manpower and the funds to properly sort out, catalog, and display its bookplates, and that’s the American Antiquarian Society,” Jaffe says. “For 18th-century bookplates, that’s an appropriate place to go and learn. But for the most part, donating bookplates to an institution is like putting them into a sinkhole because they don’t have the personnel, funds, or space to display them. I remember going into one library where I pulled down these bookplate boxes that had an inch of dust on them—nobody even knew they were up there. That’s usually what happens.”

For those hoping to start a bookplate collection of their own, Jaffe suggests joining a bookplate society like the American Society of Bookplate Collectors & Designers or The Bookplate Society (based in the U.K.), or befriending antiquarian booksellers or hand bookbinders, since they often save bookplates from volumes they’ve mended or books that were beyond repair. As far as aesthetics are concerned, a bookplate collection can focus on any subject matter or visual genre, like Art Deco or exotic birds, as ex libris imagery runs the gamut. On his blog, Jaffe has organized his bookplates into a variety of thematic micro-collections featuring imagery ranging from science fiction to Judaism, from automobiles to medicine. “I even have a group of bookplates featuring people with detached heads,” Jaffe says.

Jaffe’s collection includes a selection of plates featuring decapitated heads. (Images courtesy Lew Jaffe – click to enlarge.)

Contemporary artists are still making bookplates today, though the artwork is often designed with collectors in mind, rather than as a utilitarian craft. “The use of bookplates really follows the money,” Jaffe says. “In the Victorian age, England was all-powerful and had many wealthy people with castles and libraries, so they used bookplates. After the First World War, the English were devastated, and rich Americans were creating bookplates for their collections. You know where a tremendous amount of bookplate-collecting activity is nowadays? China.”

Regardless of the medium’s moneyed roots, Jaffe is passionate about the way bookplates shed light onto an unknown person’s private pursuits. “One of the many things I love about bookplates is that they give you a window to the past,” says Jaffe. “You see something and you wonder, ‘Who was this guy or gal?’ You can look them up on Google, and usually find out what they did and how that relates to the book. It’s like meeting someone who has been dead a hundred years.”

Beautiful Bookplates

(Unless specified, all images courtesy Lew Jaffe. See more amazing bookplates at Jaffe’s blog Confessions of a Bookplate Junkie.)

Naughty Nuns, Flatulent Monks, and Other Surprises of Sacred Medieval Manuscripts

Naughty Nuns, Flatulent Monks, and Other Surprises of Sacred Medieval Manuscripts

Cheap Thrills: The Freakish Fantasy Art of Mexican Pulp Paperbacks

Cheap Thrills: The Freakish Fantasy Art of Mexican Pulp Paperbacks Naughty Nuns, Flatulent Monks, and Other Surprises of Sacred Medieval Manuscripts

Naughty Nuns, Flatulent Monks, and Other Surprises of Sacred Medieval Manuscripts A Bookplate Junkie on the Basics of Collecting Ex Libris

A Bookplate Junkie on the Basics of Collecting Ex Libris PrintsPrintmaking is a very old art form, dating, in the case of woodblock prints…

PrintsPrintmaking is a very old art form, dating, in the case of woodblock prints… BookplatesBookplates, also known by the term ex-libris, evolved over centuries from s…

BookplatesBookplates, also known by the term ex-libris, evolved over centuries from s… BooksThere's a richness to antique books that transcends their status as one of …

BooksThere's a richness to antique books that transcends their status as one of … Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

I’m an avid reader and never really knew this had been a thing. Pretty cool. The art deco one reminded me of the cover of Atlas Shrugged and there was another that really made me thing of The Great Gatsby cover.

“In the near future, when books are looked upon as objects of pure nostalgia…”

In an otherwise excellent article it’s too bad it begins with this lemming-type of the digital cognoscente. There is zero evidence for it. But I guess it looks cooler to start with something hip and provocative and then admit it isn’t true a few sentences later.

Paper is an incredible technology and is still capable of a few profound things the screen is not. And while it’s true that paper-based publishing is diminishing, there are volumes of instances in history where objects or tools went from being widely used to moderately used. But apparently it would be too boring and unhip to take such a position.

Production and use of bookplates may have diminished, but are far from dead. You only have to visit http://www.bookplatesociety.org to find a twice-yearly journal of high quality, relating to the study of bookplates, historic and modern, and the subscription is good value. Identification of bookplates is facilitated by the CERL Provenance Query website.

I love the bookplates! Wish I was artistic and could design my own! By the way, there is something very thrilling and mysterious about handling and reading a old book (like 100 years) and wondering about all the people who may have treasured it before. So far the old books I have acquired have not contained bookplates, only names and notes from a gift giver. If only old books could talk!!!!!!!!!!!!

I love bookplates. I use them in all my books. My niece is into books so I gave her bookplates and a book journal. This was a wonderful article about a wonderful subject.

I didn’t know that bookplates were so over. I used to order mine from catalogs, even Miles Kimball sold them. There are still lots of places that sell them online but it’s also pretty easy to design and print your own at home.