Types

Food & Drink

Transportation

Other Subjects

Related Advertising

Objects

Packaging

Paper

Signs

Brands

Holidays

Subject

AD

X

Antique Porcelain Signs

We are a part of eBay Affiliate Network, and if you make a purchase through the links on our site we earn affiliate commission.

From the 1880s until the 1950s, one of the most dominant forms of outdoor advertising signage was durable, weather-resistant porcelain. Originating in Germany and imported to the United States in the 1890s, porcelain signs, also known as enamel...

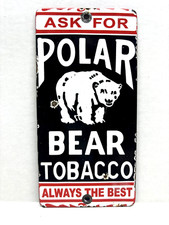

From the 1880s until the 1950s, one of the most dominant forms of outdoor advertising signage was durable, weather-resistant porcelain. Originating in Germany and imported to the United States in the 1890s, porcelain signs, also known as enamel signs or porcelain enamel signs, featured layers of powdered glass that were painstakingly fused, color by color, onto a base of heavy rolled iron, which itself would be diecut into any number of shapes.

Some signs were affixed to walls and other vertical surfaces, others were two-sided so they could be hung from a bracket or “flanged” to be read by passersby. Either way, porcelain signs usually featured bold colors and graphics, producing eye-catching and attention-getting advertisements for everything from cigars to soda pop, motor oil to automobile tires, railroad stations to telephone booths.

In the early part of the 20th century, the technique was so new to United States that the major manufacturers of porcelain signs (Enameled Iron Company and Ingram-Richardson in Pennsylvania, Baltimore Enamel & Novelty in Maryland) had to import its craftsmen from Europe.

But it wasn’t long before porcelain signs developed their own uniquely American characteristics. Silkscreens replaced the stencils, steel replaced the iron and one manufacturer, Tennessee Enamel in Nashville, made so many porcelain signs for its biggest client, Coca-Cola, that people in the United States between the wars could be forgiven for thinking the technique was as American as a bottle of Coke.

The ubiquity of porcelain signs did not last long — for collectors, that scarcity is part of the appeal. Porcelain signs eventually became targets for trigger-happy marksmen, which depleted some of the inventory. Other signs had to be discarded due to crazing and or acid etching caused by a variety of environment factors.

By far the largest destroyer of porcelain signs was World War II. Like a lot of metal objects that were melted down to support the war effort, porcelain signs were sacrificed for the base metal they contained. Prior to World War II, there were a lot of porcelain signs just lying around, since the products they advertised were no longer being sold. After the war, the cost of producing porcelain signs was simply too expensive and the practice faded from general use.

Today, porcelain signs are one of the largest categories of advertising collectibles. Some of the most prized porcelain signs are those bearing the discarded logos of current and extinct brands of gasoline. Other popular items are fun “country store” signs promoting everything from loaves of bread to house paint, as well as signs related to other things a collector has acquired (if you’ve amassed a number of vintage Ford cars, you might want an antique porcelain Ford sign for your garage).

Then there are the tried-and-true porcelain-sign collectibles — from rare railroad signs for the Union Pacific and Western Pacific lines to highway signs produced by the California Auto Club. Indeed, according to author and sign collector Michael Bruner, just about any porcelain sign with the word “California” in it is in demand. And when it comes to porcelain signs, says Bruner, size matters.

“Some of the bigger porcelain signs can actually be cheaper than the smaller signs, because they’re harder to display,” he says. That’s probably why porcelain door pulls and pushes are so popular. “Bigger doesn’t necessarily mean better.”

Continue readingFrom the 1880s until the 1950s, one of the most dominant forms of outdoor advertising signage was durable, weather-resistant porcelain. Originating in Germany and imported to the United States in the 1890s, porcelain signs, also known as enamel signs or porcelain enamel signs, featured layers of powdered glass that were painstakingly fused, color by color, onto a base of heavy rolled iron, which itself would be diecut into any number of shapes.

Some signs were affixed to walls and other vertical surfaces, others were two-sided so they could be hung from a bracket or “flanged” to be read by passersby. Either way, porcelain signs usually featured bold colors and graphics, producing eye-catching and attention-getting advertisements for everything from cigars to soda pop, motor oil to automobile tires, railroad stations to telephone booths.

In the early part of the 20th century, the technique was so new to United States that the major manufacturers of porcelain signs (Enameled Iron Company and Ingram-Richardson in Pennsylvania, Baltimore Enamel & Novelty in Maryland) had to import its craftsmen from Europe.

But it wasn’t long before porcelain signs developed their own uniquely American characteristics. Silkscreens replaced the stencils, steel replaced the iron and one manufacturer, Tennessee Enamel in Nashville, made so many porcelain signs for its biggest client, Coca-Cola, that people in the United States between the wars could be forgiven for thinking the technique was as American as a bottle of Coke.

The ubiquity of porcelain signs did not last long — for collectors, that scarcity is part of the appeal. Porcelain signs eventually became targets for trigger-happy marksmen, which depleted some of the inventory. Other signs had to be discarded due to crazing and or acid etching caused by a variety of environment factors.

By far the largest destroyer of porcelain signs was World War II. Like a lot of metal objects that were melted down to support the...

From the 1880s until the 1950s, one of the most dominant forms of outdoor advertising signage was durable, weather-resistant porcelain. Originating in Germany and imported to the United States in the 1890s, porcelain signs, also known as enamel signs or porcelain enamel signs, featured layers of powdered glass that were painstakingly fused, color by color, onto a base of heavy rolled iron, which itself would be diecut into any number of shapes.

Some signs were affixed to walls and other vertical surfaces, others were two-sided so they could be hung from a bracket or “flanged” to be read by passersby. Either way, porcelain signs usually featured bold colors and graphics, producing eye-catching and attention-getting advertisements for everything from cigars to soda pop, motor oil to automobile tires, railroad stations to telephone booths.

In the early part of the 20th century, the technique was so new to United States that the major manufacturers of porcelain signs (Enameled Iron Company and Ingram-Richardson in Pennsylvania, Baltimore Enamel & Novelty in Maryland) had to import its craftsmen from Europe.

But it wasn’t long before porcelain signs developed their own uniquely American characteristics. Silkscreens replaced the stencils, steel replaced the iron and one manufacturer, Tennessee Enamel in Nashville, made so many porcelain signs for its biggest client, Coca-Cola, that people in the United States between the wars could be forgiven for thinking the technique was as American as a bottle of Coke.

The ubiquity of porcelain signs did not last long — for collectors, that scarcity is part of the appeal. Porcelain signs eventually became targets for trigger-happy marksmen, which depleted some of the inventory. Other signs had to be discarded due to crazing and or acid etching caused by a variety of environment factors.

By far the largest destroyer of porcelain signs was World War II. Like a lot of metal objects that were melted down to support the war effort, porcelain signs were sacrificed for the base metal they contained. Prior to World War II, there were a lot of porcelain signs just lying around, since the products they advertised were no longer being sold. After the war, the cost of producing porcelain signs was simply too expensive and the practice faded from general use.

Today, porcelain signs are one of the largest categories of advertising collectibles. Some of the most prized porcelain signs are those bearing the discarded logos of current and extinct brands of gasoline. Other popular items are fun “country store” signs promoting everything from loaves of bread to house paint, as well as signs related to other things a collector has acquired (if you’ve amassed a number of vintage Ford cars, you might want an antique porcelain Ford sign for your garage).

Then there are the tried-and-true porcelain-sign collectibles — from rare railroad signs for the Union Pacific and Western Pacific lines to highway signs produced by the California Auto Club. Indeed, according to author and sign collector Michael Bruner, just about any porcelain sign with the word “California” in it is in demand. And when it comes to porcelain signs, says Bruner, size matters.

“Some of the bigger porcelain signs can actually be cheaper than the smaller signs, because they’re harder to display,” he says. That’s probably why porcelain door pulls and pushes are so popular. “Bigger doesn’t necessarily mean better.”

Continue readingMost Watched

ADX

ADX

AD

X