Cultures

Objects

Chinese

Japanese

Authors

Types

Genres

Subjects

Related

AD

X

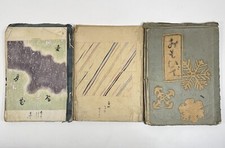

Antique and Vintage Japanese Books

We are a part of eBay Affiliate Network, and if you make a purchase through the links on our site we earn affiliate commission.

The Japanese book industry got its start in Buddhist monasteries, where monks hand-copied calligraphic scrolls called “kansubon.” However, because this format required repeated rolling and unrolling, kansubon were easily damaged and difficult to...

The Japanese book industry got its start in Buddhist monasteries, where monks hand-copied calligraphic scrolls called “kansubon.” However, because this format required repeated rolling and unrolling, kansubon were easily damaged and difficult to store safely. The leap to flat, folded pages was made around the 8th century via accordion-style books known as “orihon,” which were finished with a single-panel cover on top and bottom. Though not the earliest printed documents (the Chinese did it first in the 3rd century), Buddhist texts produced in Japan during this time appeared fully 700 years before anything came off Gutenberg's famous press.

In the 12th century, Japanese bookmakers adopted a new format known as “detchoso” or the “butterfly book.” Detchoso represented the region’s first bound books, which were made by gluing folded sheets together along their folded edges using a wheat-flour paste. The first Japanese codex book form, called “retchoso,” was simply a sewn version of the butterfly book. The texts of detchoso and retchoso books were printed on the inside of each folded sheet, meaning readers would have to skip over the blank backsides of these pages in between each facing page set.

After the 14th century, “fukuro toji,” or pouch bindings, became the most widely adopted Japanese format. To make fukuro toji, each sheet was folded so that its printed text was on the outside and then aligned so that the creases became the outer edges of a book’s pages. A book was finished by sewing the cut edges together through a series of four or five holes. This process was visible on the book’s exterior and often followed specific stitching patterns, which were given their own distinct names.

The increase in literacy and use of woodblock printing during the 17th century brought Japanese bookmaking into its own, allowing new types of secular literature to flourish along with highly detailed, colorful illustrations. Up through this period, Japanese books relied on thick, handmade papers to prevent calligraphy and woodblock ink from bleeding through the pages. However, as Western-style printing technology spread through Japan in the late 19th century, the region’s traditional book designs began to decline.

Continue readingThe Japanese book industry got its start in Buddhist monasteries, where monks hand-copied calligraphic scrolls called “kansubon.” However, because this format required repeated rolling and unrolling, kansubon were easily damaged and difficult to store safely. The leap to flat, folded pages was made around the 8th century via accordion-style books known as “orihon,” which were finished with a single-panel cover on top and bottom. Though not the earliest printed documents (the Chinese did it first in the 3rd century), Buddhist texts produced in Japan during this time appeared fully 700 years before anything came off Gutenberg's famous press.

In the 12th century, Japanese bookmakers adopted a new format known as “detchoso” or the “butterfly book.” Detchoso represented the region’s first bound books, which were made by gluing folded sheets together along their folded edges using a wheat-flour paste. The first Japanese codex book form, called “retchoso,” was simply a sewn version of the butterfly book. The texts of detchoso and retchoso books were printed on the inside of each folded sheet, meaning readers would have to skip over the blank backsides of these pages in between each facing page set.

After the 14th century, “fukuro toji,” or pouch bindings, became the most widely adopted Japanese format. To make fukuro toji, each sheet was folded so that its printed text was on the outside and then aligned so that the creases became the outer edges of a book’s pages. A book was finished by sewing the cut edges together through a series of four or five holes. This process was visible on the book’s exterior and often followed specific stitching patterns, which were given their own distinct names.

The increase in literacy and use of woodblock printing during the 17th century brought Japanese bookmaking into its own, allowing new types of secular literature to flourish along with highly detailed, colorful illustrations. Up through this period, Japanese books relied...

The Japanese book industry got its start in Buddhist monasteries, where monks hand-copied calligraphic scrolls called “kansubon.” However, because this format required repeated rolling and unrolling, kansubon were easily damaged and difficult to store safely. The leap to flat, folded pages was made around the 8th century via accordion-style books known as “orihon,” which were finished with a single-panel cover on top and bottom. Though not the earliest printed documents (the Chinese did it first in the 3rd century), Buddhist texts produced in Japan during this time appeared fully 700 years before anything came off Gutenberg's famous press.

In the 12th century, Japanese bookmakers adopted a new format known as “detchoso” or the “butterfly book.” Detchoso represented the region’s first bound books, which were made by gluing folded sheets together along their folded edges using a wheat-flour paste. The first Japanese codex book form, called “retchoso,” was simply a sewn version of the butterfly book. The texts of detchoso and retchoso books were printed on the inside of each folded sheet, meaning readers would have to skip over the blank backsides of these pages in between each facing page set.

After the 14th century, “fukuro toji,” or pouch bindings, became the most widely adopted Japanese format. To make fukuro toji, each sheet was folded so that its printed text was on the outside and then aligned so that the creases became the outer edges of a book’s pages. A book was finished by sewing the cut edges together through a series of four or five holes. This process was visible on the book’s exterior and often followed specific stitching patterns, which were given their own distinct names.

The increase in literacy and use of woodblock printing during the 17th century brought Japanese bookmaking into its own, allowing new types of secular literature to flourish along with highly detailed, colorful illustrations. Up through this period, Japanese books relied on thick, handmade papers to prevent calligraphy and woodblock ink from bleeding through the pages. However, as Western-style printing technology spread through Japan in the late 19th century, the region’s traditional book designs began to decline.

Continue readingMost Watched

ADX

ADX

AD

X