Authors

Types

Genres

Subjects

Related

AD

X

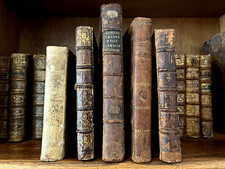

Antique and Vintage History Books

We are a part of eBay Affiliate Network, and if you make a purchase through the links on our site we earn affiliate commission.

“History repeats itself. Historians repeat each other.” So said the early 20th-century biographer Philip Guedalla, who, as something of a historian himself, knew what he was talking about. But history books are collected for more than their...

“History repeats itself. Historians repeat each other.” So said the early 20th-century biographer Philip Guedalla, who, as something of a historian himself, knew what he was talking about. But history books are collected for more than their occasionally plagiarized contents. And when it comes to vintage and antique titles, the ever-evolving narrative of world events, from the rise and fall of the Roman empire to the settling of Australia by Westerners, can reveal how the biases of the times can affect what ends up on the printed page.

Some of the oldest history books are those that documented the numerous voyages of discovery in the 15th and 16th centuries. In general, antique books from these centuries are judged by their condition and completeness rather than whether they happen to be first or subsequent printing. In addition, histories about these voyages were generally collections of numerous sailings rather than a dutiful diarist’s account of just one. One of the most famous examples of this form is Samuel Purchas’s “Purchas His Pilgrimes,” published in 1625.

Like many similar tracts, “Purchas His Pilgrimes” was reprinted hundreds of years later by the Hakluyt Society, whose original members in 1847 included Charles Darwin. Named for Richard Hakluyt, whose “The Principal Navigations Voiages and Discoveries of the English Nation” was published in 1589, the society reprinted accounts of voyages undertaken by Christopher Columbus, Ferdinand Magellan, Captain James Cook, Vasco da Gama, Sir Francis Drake, and George Vancouver. Later, in the 20th century, Argonaut Press and other publishers did roughly the same thing.

In fact, this sea-faring genre of historical non-fiction was so popular, its titles were often remade as children’s books. The “Historical Account of the most celebrated Voyages, Travels and Discoveries,” 1796, was published by E. Newbery, who enjoyed so much success with the series aimed at younger readers that it grew to 25 volumes. Other works, such as John Josselyn’s “An Account of Two Voyages to New England,” which was published by Giles Widdows of London in 1674, are inadvertent histories (the main goal of this document was to catalog the flora and fauna of the New World).

Some voyages, and even their leaders, are genres all their own. For example, each of Captain James Cook’s three voyages in the 18th century were well documented. John Hawkesworth wrote the official account of Cook’s first voyage in the Southern Hemisphere (1773), but Sydney Parkinson’s version is more prized by collectors, mostly because as the draftsman on the HMS Endeavor, Parkinson’s includes hand-colored engravings. Books focused on expeditions in North America include “The Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition” of 1803 (13 volumes were published in 1983 by the University of Nebraska Press), as well as Captain John C. Fremont’s probes into the Rocky Mountains—antique copies of these titles from the 1840s are collected in no small part for their illustrations and maps.

Then there are books about our obsession with the north and south poles. While there’s some debate about whether Dr. Frederick A. Cook or Robert E. Peary reached the north pole first in 1908 or 1909 respectively (see “True North: Peary, Cook, and the Race to the Pole,” by Bruce Henderson, 2005), history-book collectors often seek out the account by Rear Admiral William Edward Parry, whose “Narrative of an Attempt to Reach the North Pole in Boats Fitted for the Purpose and Attached to His Majesty's Ship Hecla in the Year MDCCCXXVII, Under the Command of Captain William Edward Parry, RN, FRS” was published by John Murray of London in 1828. The 12-volume record of Robert Scott’s 1901-1904 expedition to Antarctica, includes color plates by Edward Wilson, while Sir Ernest Shackleton’s “Aurora Australis, (1908) was produced entirely by Shackleton and his crew.

Cookbooks and titles on enology can also be windows on history. For example, “The London Art of Cookery,” 1783, by John Farley, is a time capsule of late-18th-century tavern fare. Cyrus Redding’s “A History and Description of of Modern Wines,” 1833, was enlarged to include port in 1836. And Henry Viztelly’s “History of Champagne,” 1882, is obviously a specialized history within the broader subject of wine.

Still, for many, history books on wars remain the biggest prizes, although sometimes the most interesting titles are the ones that are the least official. For example, there are lots of books about the Civil War, including “A Stillness at Appomattox” by Bruce Catton, which won the Pulitzer Prize in 1954, and Shelby Foote’s “The Civil War: A Narrative,” published in three volumes between 1958 and 1974. But Civil War regimental histories are of more interest to some collectors because they were written by the actual soldiers on both sides of the conflict who witnessed battles firsthand. Originally published in the late 19th century, sometimes in limited editions, a lot of these regimentals, as they are sometimes called, have been reprinted in recent years, which has made these historical accounts more accessible to collectors.

Of course, World War I was famously documented by Winston Churchill in “The World Crisis,” a six-volume set published between 1923 and 1931. Churchill’s six-volume follow up about World War II was released between 1948 and 1954. Though not as rare as the English versions, the United States editions conjure nostalgic memories for some collectors—the checkered effect of the jacket spines was instantly recognizable in American libraries and dens throughout the 1950s and ’60s.

Continue reading“History repeats itself. Historians repeat each other.” So said the early 20th-century biographer Philip Guedalla, who, as something of a historian himself, knew what he was talking about. But history books are collected for more than their occasionally plagiarized contents. And when it comes to vintage and antique titles, the ever-evolving narrative of world events, from the rise and fall of the Roman empire to the settling of Australia by Westerners, can reveal how the biases of the times can affect what ends up on the printed page.

Some of the oldest history books are those that documented the numerous voyages of discovery in the 15th and 16th centuries. In general, antique books from these centuries are judged by their condition and completeness rather than whether they happen to be first or subsequent printing. In addition, histories about these voyages were generally collections of numerous sailings rather than a dutiful diarist’s account of just one. One of the most famous examples of this form is Samuel Purchas’s “Purchas His Pilgrimes,” published in 1625.

Like many similar tracts, “Purchas His Pilgrimes” was reprinted hundreds of years later by the Hakluyt Society, whose original members in 1847 included Charles Darwin. Named for Richard Hakluyt, whose “The Principal Navigations Voiages and Discoveries of the English Nation” was published in 1589, the society reprinted accounts of voyages undertaken by Christopher Columbus, Ferdinand Magellan, Captain James Cook, Vasco da Gama, Sir Francis Drake, and George Vancouver. Later, in the 20th century, Argonaut Press and other publishers did roughly the same thing.

In fact, this sea-faring genre of historical non-fiction was so popular, its titles were often remade as children’s books. The “Historical Account of the most celebrated Voyages, Travels and Discoveries,” 1796, was published by E. Newbery, who enjoyed so much success with the series aimed at younger readers that it grew to 25 volumes. Other...

“History repeats itself. Historians repeat each other.” So said the early 20th-century biographer Philip Guedalla, who, as something of a historian himself, knew what he was talking about. But history books are collected for more than their occasionally plagiarized contents. And when it comes to vintage and antique titles, the ever-evolving narrative of world events, from the rise and fall of the Roman empire to the settling of Australia by Westerners, can reveal how the biases of the times can affect what ends up on the printed page.

Some of the oldest history books are those that documented the numerous voyages of discovery in the 15th and 16th centuries. In general, antique books from these centuries are judged by their condition and completeness rather than whether they happen to be first or subsequent printing. In addition, histories about these voyages were generally collections of numerous sailings rather than a dutiful diarist’s account of just one. One of the most famous examples of this form is Samuel Purchas’s “Purchas His Pilgrimes,” published in 1625.

Like many similar tracts, “Purchas His Pilgrimes” was reprinted hundreds of years later by the Hakluyt Society, whose original members in 1847 included Charles Darwin. Named for Richard Hakluyt, whose “The Principal Navigations Voiages and Discoveries of the English Nation” was published in 1589, the society reprinted accounts of voyages undertaken by Christopher Columbus, Ferdinand Magellan, Captain James Cook, Vasco da Gama, Sir Francis Drake, and George Vancouver. Later, in the 20th century, Argonaut Press and other publishers did roughly the same thing.

In fact, this sea-faring genre of historical non-fiction was so popular, its titles were often remade as children’s books. The “Historical Account of the most celebrated Voyages, Travels and Discoveries,” 1796, was published by E. Newbery, who enjoyed so much success with the series aimed at younger readers that it grew to 25 volumes. Other works, such as John Josselyn’s “An Account of Two Voyages to New England,” which was published by Giles Widdows of London in 1674, are inadvertent histories (the main goal of this document was to catalog the flora and fauna of the New World).

Some voyages, and even their leaders, are genres all their own. For example, each of Captain James Cook’s three voyages in the 18th century were well documented. John Hawkesworth wrote the official account of Cook’s first voyage in the Southern Hemisphere (1773), but Sydney Parkinson’s version is more prized by collectors, mostly because as the draftsman on the HMS Endeavor, Parkinson’s includes hand-colored engravings. Books focused on expeditions in North America include “The Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition” of 1803 (13 volumes were published in 1983 by the University of Nebraska Press), as well as Captain John C. Fremont’s probes into the Rocky Mountains—antique copies of these titles from the 1840s are collected in no small part for their illustrations and maps.

Then there are books about our obsession with the north and south poles. While there’s some debate about whether Dr. Frederick A. Cook or Robert E. Peary reached the north pole first in 1908 or 1909 respectively (see “True North: Peary, Cook, and the Race to the Pole,” by Bruce Henderson, 2005), history-book collectors often seek out the account by Rear Admiral William Edward Parry, whose “Narrative of an Attempt to Reach the North Pole in Boats Fitted for the Purpose and Attached to His Majesty's Ship Hecla in the Year MDCCCXXVII, Under the Command of Captain William Edward Parry, RN, FRS” was published by John Murray of London in 1828. The 12-volume record of Robert Scott’s 1901-1904 expedition to Antarctica, includes color plates by Edward Wilson, while Sir Ernest Shackleton’s “Aurora Australis, (1908) was produced entirely by Shackleton and his crew.

Cookbooks and titles on enology can also be windows on history. For example, “The London Art of Cookery,” 1783, by John Farley, is a time capsule of late-18th-century tavern fare. Cyrus Redding’s “A History and Description of of Modern Wines,” 1833, was enlarged to include port in 1836. And Henry Viztelly’s “History of Champagne,” 1882, is obviously a specialized history within the broader subject of wine.

Still, for many, history books on wars remain the biggest prizes, although sometimes the most interesting titles are the ones that are the least official. For example, there are lots of books about the Civil War, including “A Stillness at Appomattox” by Bruce Catton, which won the Pulitzer Prize in 1954, and Shelby Foote’s “The Civil War: A Narrative,” published in three volumes between 1958 and 1974. But Civil War regimental histories are of more interest to some collectors because they were written by the actual soldiers on both sides of the conflict who witnessed battles firsthand. Originally published in the late 19th century, sometimes in limited editions, a lot of these regimentals, as they are sometimes called, have been reprinted in recent years, which has made these historical accounts more accessible to collectors.

Of course, World War I was famously documented by Winston Churchill in “The World Crisis,” a six-volume set published between 1923 and 1931. Churchill’s six-volume follow up about World War II was released between 1948 and 1954. Though not as rare as the English versions, the United States editions conjure nostalgic memories for some collectors—the checkered effect of the jacket spines was instantly recognizable in American libraries and dens throughout the 1950s and ’60s.

Continue readingBest of the Web

Bookscans.com

Bruce Black's gallery of paperback book covers from the 1940s and 50s. With help from numerous...

Google Book Search

Want to do one quick search and pull up the mother lode of vintage books? Try Google Book...

Club & Associations

Most Watched

ADX

Best of the Web

Bookscans.com

Bruce Black's gallery of paperback book covers from the 1940s and 50s. With help from numerous...

Google Book Search

Want to do one quick search and pull up the mother lode of vintage books? Try Google Book...

Club & Associations

ADX

AD

X

![[1786] Barnard HISTORY OF ENGLAND Reigns Government Wars Maps 104 Plates](https://i.ebayimg.com/images/g/E4IAAOSwfX1n~RHk/s-l225.jpg)