Eras

Characters

Publishers

Other Comics

AD

X

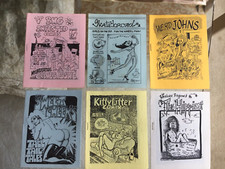

Underground and Alternative Comics

We are a part of eBay Affiliate Network, and if you make a purchase through the links on our site we earn affiliate commission.

If 1967 was the year American pop culture embraced the flower-power ethos of the hippie movement, 1968 was definitely the year the bloom faded from the rose. In 1968, opposition to the Vietnam War brought down a sitting president, Civil Rights...

If 1967 was the year American pop culture embraced the flower-power ethos of the hippie movement, 1968 was definitely the year the bloom faded from the rose. In 1968, opposition to the Vietnam War brought down a sitting president, Civil Rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated, presidential candidate Robert Kennedy was murdered two months after that, and the popularity of mind-expanding psychedelic drugs was eclipsed by a worrying preference for toxic chemicals that transformed their young users into burned-out speed freaks and nodding junkies.

From this disquieting cultural milieu, underground comix were born. Ignoring the content guidelines of the Comics Code Authority, whose seal was prominently displayed on the covers of comic books published by the likes of Marvel and DC, the genre is generally thought to have been born in February of 1968, when Zap Comix #1 was released by Apex Novelties of San Francisco. Featuring a cover warning that its contents were intended “For Adult Intellectuals Only!” and written entirely by Robert Crumb, Zap would quickly become a vehicle for rock-poster artists Rick Griffin and Victor Moscoso, “Checkered Demon” creator S. Clay Wilson, and Gilbert Shelton, who today is best known for his underground comic-book series based on a trio of lovable-loser stoners known as the Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers.

As a genre, underground comix were unrepentantly, even gleefully, amoral. It was almost as if underground-comix artists had taken the list of everything that was banned by the Comics Code Authority and made that their content guidelines. Thus, the pages of underground comix were filled with graphic depictions of everything from rape and murder to less egregious acts of run-of-the-mill depravity. For example, concurrent with the first few issues of Zap, Crumb and Wilson penned three issues of lewd and sexually explicit content via a title called Snatch. But unlike many of his contemporaries, Crumb occasionally explored topics that were more existential in nature, as in the one-shot issue of a 1969 comic called Despair.

Then, in August 1969, the same month half a million hippies descended on a farm in upstate New York to attend Woodstock, Zap Comix #4 was published. Zap had long since dropped the word “Intellectuals” from its cover warning, but the “Adults Only” label that replaced it was not enough to prevent the arrest of the comic’s publishers, as well as several New York City booksellers who stocked Zap alongside other titles. By the fall of 1970, a New York court had ruled that Zap Comix #4 had violated the state’s obscenity law, a ruling that would withstand numerous appeals—lest it go without saying, today, Zap Comix #4 is widely and legally available from any number of sources.

During the 1970s, the trail blazed by Zap would become a heavily trafficked expressway of adults-only fare. In 1971, Crumb penned the first and only issue of Your Hytone Comics, which was the same year the first issue of Gilbert Shelton’s The Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers was published. Vaughn Bode’s Cheech Wizard series began in 1972.

But the 1970s also saw the dawn of Ron Turner’s venerable publishing enterprise, Last Gasp, which debuted in 1970 with Slow Death Funnies. With its cover by yet another rock-poster artist, Greg Irons, Slow Death Funnies and the 10 issues of the renamed Slow Death that followed over the next 20 years focused on environmental issues, particularly as they related to the role of corporate capitalism in the defilement of the planet.

That same year, Last Gasp provided an antidote to the mostly misogynist content of underground comix by giving Trina Robbins and Barbara "Willy" Mendes editorial control over It Ain’t Me Babe, which featured contributions by Robbins, Mendes, and other female artists, including Meredith Kurtzman, whose father, Harvey Kurtzman, had been the founding editor of Mad magazine in the 1950s. Although It Ain’t Me Babe was a one-shot, Last Gasp would commit to a series written by and for female readers called Wimmen’s Comix in 1972. Another key underground comic of the 1970s and beyond was American Splendor, which was written by Harvey Pekar and illustrated by cartoonists from Crumb to Gary Dumm.

By the 1980s, underground comix were beginning to feel tired to a new generation of artists who wanted to tell stories via their talents as illustrators and writers. Thus, alternative comics were born with the launch of the self-published Raw magazine, edited by Art Spiegelman and Françoise Mouly from 1980 until 1986. Printed in a much larger format than comic books or even magazines of the day, Raw offered lots of room for artists to express themselves in ways that were truly original. For example, Spiegelman serialized all but the last chapter of his graphic novel called Maus in Raw—many chapters were published while Spiegelman was working on the debut series of Garbage Pail Kids trading cards.

Crumb, too, found a home in this new world of alternative comics by contributing many of the covers and much of the content to Last Gasp’s Weirdo from 1981 to 1993, many of whose issues were edited by either Crumb or his wife, Aline Kominsky-Crumb. Another important comic of the alternative-comics era was Love and Rockets, which is the work of three brothers, Jaime, Gilbert, and Mario Hernandez, who self-published the comic in 1981 before Fantagraphics republished an expanded version of issue #1 in 1982 and then restarted it as a series.

Continue readingIf 1967 was the year American pop culture embraced the flower-power ethos of the hippie movement, 1968 was definitely the year the bloom faded from the rose. In 1968, opposition to the Vietnam War brought down a sitting president, Civil Rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated, presidential candidate Robert Kennedy was murdered two months after that, and the popularity of mind-expanding psychedelic drugs was eclipsed by a worrying preference for toxic chemicals that transformed their young users into burned-out speed freaks and nodding junkies.

From this disquieting cultural milieu, underground comix were born. Ignoring the content guidelines of the Comics Code Authority, whose seal was prominently displayed on the covers of comic books published by the likes of Marvel and DC, the genre is generally thought to have been born in February of 1968, when Zap Comix #1 was released by Apex Novelties of San Francisco. Featuring a cover warning that its contents were intended “For Adult Intellectuals Only!” and written entirely by Robert Crumb, Zap would quickly become a vehicle for rock-poster artists Rick Griffin and Victor Moscoso, “Checkered Demon” creator S. Clay Wilson, and Gilbert Shelton, who today is best known for his underground comic-book series based on a trio of lovable-loser stoners known as the Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers.

As a genre, underground comix were unrepentantly, even gleefully, amoral. It was almost as if underground-comix artists had taken the list of everything that was banned by the Comics Code Authority and made that their content guidelines. Thus, the pages of underground comix were filled with graphic depictions of everything from rape and murder to less egregious acts of run-of-the-mill depravity. For example, concurrent with the first few issues of Zap, Crumb and Wilson penned three issues of lewd and sexually explicit content via a title called Snatch. But unlike many of his contemporaries, Crumb occasionally...

If 1967 was the year American pop culture embraced the flower-power ethos of the hippie movement, 1968 was definitely the year the bloom faded from the rose. In 1968, opposition to the Vietnam War brought down a sitting president, Civil Rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated, presidential candidate Robert Kennedy was murdered two months after that, and the popularity of mind-expanding psychedelic drugs was eclipsed by a worrying preference for toxic chemicals that transformed their young users into burned-out speed freaks and nodding junkies.

From this disquieting cultural milieu, underground comix were born. Ignoring the content guidelines of the Comics Code Authority, whose seal was prominently displayed on the covers of comic books published by the likes of Marvel and DC, the genre is generally thought to have been born in February of 1968, when Zap Comix #1 was released by Apex Novelties of San Francisco. Featuring a cover warning that its contents were intended “For Adult Intellectuals Only!” and written entirely by Robert Crumb, Zap would quickly become a vehicle for rock-poster artists Rick Griffin and Victor Moscoso, “Checkered Demon” creator S. Clay Wilson, and Gilbert Shelton, who today is best known for his underground comic-book series based on a trio of lovable-loser stoners known as the Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers.

As a genre, underground comix were unrepentantly, even gleefully, amoral. It was almost as if underground-comix artists had taken the list of everything that was banned by the Comics Code Authority and made that their content guidelines. Thus, the pages of underground comix were filled with graphic depictions of everything from rape and murder to less egregious acts of run-of-the-mill depravity. For example, concurrent with the first few issues of Zap, Crumb and Wilson penned three issues of lewd and sexually explicit content via a title called Snatch. But unlike many of his contemporaries, Crumb occasionally explored topics that were more existential in nature, as in the one-shot issue of a 1969 comic called Despair.

Then, in August 1969, the same month half a million hippies descended on a farm in upstate New York to attend Woodstock, Zap Comix #4 was published. Zap had long since dropped the word “Intellectuals” from its cover warning, but the “Adults Only” label that replaced it was not enough to prevent the arrest of the comic’s publishers, as well as several New York City booksellers who stocked Zap alongside other titles. By the fall of 1970, a New York court had ruled that Zap Comix #4 had violated the state’s obscenity law, a ruling that would withstand numerous appeals—lest it go without saying, today, Zap Comix #4 is widely and legally available from any number of sources.

During the 1970s, the trail blazed by Zap would become a heavily trafficked expressway of adults-only fare. In 1971, Crumb penned the first and only issue of Your Hytone Comics, which was the same year the first issue of Gilbert Shelton’s The Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers was published. Vaughn Bode’s Cheech Wizard series began in 1972.

But the 1970s also saw the dawn of Ron Turner’s venerable publishing enterprise, Last Gasp, which debuted in 1970 with Slow Death Funnies. With its cover by yet another rock-poster artist, Greg Irons, Slow Death Funnies and the 10 issues of the renamed Slow Death that followed over the next 20 years focused on environmental issues, particularly as they related to the role of corporate capitalism in the defilement of the planet.

That same year, Last Gasp provided an antidote to the mostly misogynist content of underground comix by giving Trina Robbins and Barbara "Willy" Mendes editorial control over It Ain’t Me Babe, which featured contributions by Robbins, Mendes, and other female artists, including Meredith Kurtzman, whose father, Harvey Kurtzman, had been the founding editor of Mad magazine in the 1950s. Although It Ain’t Me Babe was a one-shot, Last Gasp would commit to a series written by and for female readers called Wimmen’s Comix in 1972. Another key underground comic of the 1970s and beyond was American Splendor, which was written by Harvey Pekar and illustrated by cartoonists from Crumb to Gary Dumm.

By the 1980s, underground comix were beginning to feel tired to a new generation of artists who wanted to tell stories via their talents as illustrators and writers. Thus, alternative comics were born with the launch of the self-published Raw magazine, edited by Art Spiegelman and Françoise Mouly from 1980 until 1986. Printed in a much larger format than comic books or even magazines of the day, Raw offered lots of room for artists to express themselves in ways that were truly original. For example, Spiegelman serialized all but the last chapter of his graphic novel called Maus in Raw—many chapters were published while Spiegelman was working on the debut series of Garbage Pail Kids trading cards.

Crumb, too, found a home in this new world of alternative comics by contributing many of the covers and much of the content to Last Gasp’s Weirdo from 1981 to 1993, many of whose issues were edited by either Crumb or his wife, Aline Kominsky-Crumb. Another important comic of the alternative-comics era was Love and Rockets, which is the work of three brothers, Jaime, Gilbert, and Mario Hernandez, who self-published the comic in 1981 before Fantagraphics republished an expanded version of issue #1 in 1982 and then restarted it as a series.

Continue readingBest of the Web

Cover Browser

Philipp Lenssen's incredible archive of over 94,000 comic book covers - Wow! Wham! Yikes! Browse...

Barnacle Press

This collection of obscure newspaper comic strips provides scans browsable by title, year and...

Most Watched

ADX

Best of the Web

Cover Browser

Philipp Lenssen's incredible archive of over 94,000 comic book covers - Wow! Wham! Yikes! Browse...

Barnacle Press

This collection of obscure newspaper comic strips provides scans browsable by title, year and...

ADX

AD

X