Format

Genre

Artists

Players

Album Design

Other Vinyl

Other Audio Formats

AD

X

Vintage Shellac Records

We are a part of eBay Affiliate Network, and if you make a purchase through the links on our site we earn affiliate commission.

The origin story behind the naming of The Beatles is famously murky, although many sources agree that the name was at least briefly spelled with two "e"s as an insectile homage to Buddy Holly and the Crickets.

Unwittingly, the bug reference...

The origin story behind the naming of The Beatles is famously murky, although many sources agree that the name was at least briefly spelled with two "e"s as an insectile homage to Buddy Holly and the Crickets.

Unwittingly, the bug reference also turned out to be related to the early days of records, when discs were made from the resinous "lac" secretions of a scaly insect known as kerria lacca, which is native to India and other parts of South Asia. In India, lac had been harvested by villagers for hundreds of years for use as a resin or polish for furniture.

In 1894, a German-born American inventor named Emile Berliner used this raw material—in combination with finely ground rocks like limestone or pumice, carbon black, and cotton flock—to produce shellac records, which were big improvements over the "plates" he'd been pressing out of celluloid and rubber-based materials. Shellac records were brittle, but they delivered a better range of sound than anything that had come before.

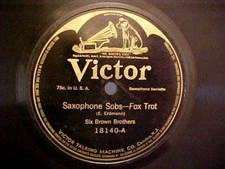

Berliner's first shellac records were seven inches wide, but by 1900 shellac records were being pressed by Berliner and others in 10- and 12-inch widths. For about a decade, these records, regardless of their diameter, were single sided, but in 1904, a couple of German record manufacturers, Beka and Odeon companies, started pressing double-sided records. That became standard practice by the end of the decade when U.S. record manufacturers followed suit, although there were exceptions, as the decision by the Victor Talking Machine Company to release its classical records stamped with its Red Seal label as single-sided all the way until the early 1920s.

The speed at which these records spun on Berliner's Gramophones and Eldridge Johnson’s Victorolas, made by the Victor Talking Machine Company, the forerunner of RCA Victor, was initially not precise, wavering between 78 to 80 revolutions per minute, or rpm. By 1925, the standard speed was set at 78.26 rpm, mostly because the speed was easy to achieve via the 3600-rpm motors and 46-teeth gears that were used in most phonographs of the day.

Today, we think of these records as 78s, but it was actually not until after the end of World War II that the term came into vogue. Until that time, records were simply records, a generic term that was used to differentiate them from the early cylinders that had been championed by Edison and other manufacturers. Concurrently, record manufacturers were introducing records that turned at 16, 33 1/3, and 45 rpm, which meant that shellac records began to be widely known as 78s.

But, as it would turn out, shellac itself was about to disappear from the recorded-music lexicon. During the war, shellac had been rationed to help with the war effort, replaced by a new material called Vinylite. Although some manufacturers such as Columbia had introduced laminated shellac discs to make them more durable, the surfaces of these discs were soft, which caused the needles on the ends of phonograph arms to wear down the wide grooves relatively quickly. In comparison, Vinylite was both flexible—less brittle—and tough, which allowed these new records to be imprinted with 224 to 300 grooves per inch rather than the meager 85 grooves per inch common on shellac. That meant more music could be sold on a single disc, which was a boon to the postwar record business.

For collectors of vintage shellac records, the early discs pressed by the Gramophone Company of England are prized, no doubt because the English had a monopoly on the shellac being exported from its colony of India, which meant the British manufacturers could keep the highest quality raw materials for themselves. Other early brands of shellac records were Berliner's Gramophone in the U.S. and Canada, RCA Victor, Brunswick, Columbia, Edison, and Pathe from France. Bargain brands made of inferior blends of shellac included Madison, Clover, Bluebird, Okeh, Vocalion, and Globe.

As for The Beatles, they would be one of the last musical groups to see a catalog of their hits released on shellac. From 1964 until 1968, the Indian branch of British record manufacturer Parlophone pressed a total of 30 Beatles 78s on 10-inch shellac discs. The ostensible reason, of course, was that The Beatles were enormous international stars, but it didn't hurt that countless music fans in India still listened to music on hand-cranked machines designs to play shellac records. Thus, the band that was almost named after a bug found its music pressed onto discs in the land where the bugs used to make shellac records lived and died.

Continue readingThe origin story behind the naming of The Beatles is famously murky, although many sources agree that the name was at least briefly spelled with two "e"s as an insectile homage to Buddy Holly and the Crickets.

Unwittingly, the bug reference also turned out to be related to the early days of records, when discs were made from the resinous "lac" secretions of a scaly insect known as kerria lacca, which is native to India and other parts of South Asia. In India, lac had been harvested by villagers for hundreds of years for use as a resin or polish for furniture.

In 1894, a German-born American inventor named Emile Berliner used this raw material—in combination with finely ground rocks like limestone or pumice, carbon black, and cotton flock—to produce shellac records, which were big improvements over the "plates" he'd been pressing out of celluloid and rubber-based materials. Shellac records were brittle, but they delivered a better range of sound than anything that had come before.

Berliner's first shellac records were seven inches wide, but by 1900 shellac records were being pressed by Berliner and others in 10- and 12-inch widths. For about a decade, these records, regardless of their diameter, were single sided, but in 1904, a couple of German record manufacturers, Beka and Odeon companies, started pressing double-sided records. That became standard practice by the end of the decade when U.S. record manufacturers followed suit, although there were exceptions, as the decision by the Victor Talking Machine Company to release its classical records stamped with its Red Seal label as single-sided all the way until the early 1920s.

The speed at which these records spun on Berliner's Gramophones and Eldridge Johnson’s Victorolas, made by the Victor Talking Machine Company, the forerunner of RCA Victor, was initially not precise, wavering between 78 to 80 revolutions per minute, or rpm. By 1925, the standard speed was set at 78.26 rpm, mostly because the...

The origin story behind the naming of The Beatles is famously murky, although many sources agree that the name was at least briefly spelled with two "e"s as an insectile homage to Buddy Holly and the Crickets.

Unwittingly, the bug reference also turned out to be related to the early days of records, when discs were made from the resinous "lac" secretions of a scaly insect known as kerria lacca, which is native to India and other parts of South Asia. In India, lac had been harvested by villagers for hundreds of years for use as a resin or polish for furniture.

In 1894, a German-born American inventor named Emile Berliner used this raw material—in combination with finely ground rocks like limestone or pumice, carbon black, and cotton flock—to produce shellac records, which were big improvements over the "plates" he'd been pressing out of celluloid and rubber-based materials. Shellac records were brittle, but they delivered a better range of sound than anything that had come before.

Berliner's first shellac records were seven inches wide, but by 1900 shellac records were being pressed by Berliner and others in 10- and 12-inch widths. For about a decade, these records, regardless of their diameter, were single sided, but in 1904, a couple of German record manufacturers, Beka and Odeon companies, started pressing double-sided records. That became standard practice by the end of the decade when U.S. record manufacturers followed suit, although there were exceptions, as the decision by the Victor Talking Machine Company to release its classical records stamped with its Red Seal label as single-sided all the way until the early 1920s.

The speed at which these records spun on Berliner's Gramophones and Eldridge Johnson’s Victorolas, made by the Victor Talking Machine Company, the forerunner of RCA Victor, was initially not precise, wavering between 78 to 80 revolutions per minute, or rpm. By 1925, the standard speed was set at 78.26 rpm, mostly because the speed was easy to achieve via the 3600-rpm motors and 46-teeth gears that were used in most phonographs of the day.

Today, we think of these records as 78s, but it was actually not until after the end of World War II that the term came into vogue. Until that time, records were simply records, a generic term that was used to differentiate them from the early cylinders that had been championed by Edison and other manufacturers. Concurrently, record manufacturers were introducing records that turned at 16, 33 1/3, and 45 rpm, which meant that shellac records began to be widely known as 78s.

But, as it would turn out, shellac itself was about to disappear from the recorded-music lexicon. During the war, shellac had been rationed to help with the war effort, replaced by a new material called Vinylite. Although some manufacturers such as Columbia had introduced laminated shellac discs to make them more durable, the surfaces of these discs were soft, which caused the needles on the ends of phonograph arms to wear down the wide grooves relatively quickly. In comparison, Vinylite was both flexible—less brittle—and tough, which allowed these new records to be imprinted with 224 to 300 grooves per inch rather than the meager 85 grooves per inch common on shellac. That meant more music could be sold on a single disc, which was a boon to the postwar record business.

For collectors of vintage shellac records, the early discs pressed by the Gramophone Company of England are prized, no doubt because the English had a monopoly on the shellac being exported from its colony of India, which meant the British manufacturers could keep the highest quality raw materials for themselves. Other early brands of shellac records were Berliner's Gramophone in the U.S. and Canada, RCA Victor, Brunswick, Columbia, Edison, and Pathe from France. Bargain brands made of inferior blends of shellac included Madison, Clover, Bluebird, Okeh, Vocalion, and Globe.

As for The Beatles, they would be one of the last musical groups to see a catalog of their hits released on shellac. From 1964 until 1968, the Indian branch of British record manufacturer Parlophone pressed a total of 30 Beatles 78s on 10-inch shellac discs. The ostensible reason, of course, was that The Beatles were enormous international stars, but it didn't hurt that countless music fans in India still listened to music on hand-cranked machines designs to play shellac records. Thus, the band that was almost named after a bug found its music pressed onto discs in the land where the bugs used to make shellac records lived and died.

Continue readingBest of the Web

Mybeatles.net

Jesse Barron's collection of Beatles 45s, picture sleeves, magazines, books, and memorabilia....

Association of Vogue Picture Record Collectors

This great site, from the Association of Vogue Picture Record Collectors, offers detailed...

Vinyl Divas

Vinyl Divas pays homage to international female opera singers of the LP era. Chronicling more...

317X

Despite its mysterious title, 317X is plain and simple—an online gallery of vintage LPs, with a...

Club & Associations

Most Watched

ADX

Best of the Web

Mybeatles.net

Jesse Barron's collection of Beatles 45s, picture sleeves, magazines, books, and memorabilia....

Association of Vogue Picture Record Collectors

This great site, from the Association of Vogue Picture Record Collectors, offers detailed...

Vinyl Divas

Vinyl Divas pays homage to international female opera singers of the LP era. Chronicling more...

317X

Despite its mysterious title, 317X is plain and simple—an online gallery of vintage LPs, with a...

Club & Associations

ADX

AD

X

![BENNIE MOTEN'S KANSAS CITY ORCHESTRA "Midnight Mama" VICTOR 20422 [78 RPM]](https://i.ebayimg.com/images/g/AfIAAOSwJoVnK0hL/s-l225.jpg)

![CAROLINA CLUB ORCHESTRA (London 1924) "Ain't You Ashamed" COLUMBIA; Rare! [78]](https://i.ebayimg.com/images/g/9l8AAOSwdrNnrgDX/s-l225.jpg)