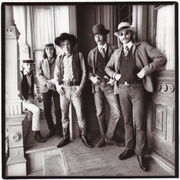

Hogsnort Rupert and his Good Good Band, performing at Ricky-Tick in Clewer Mead, Windsor, circa February or March, 1965. Photo courtesy As You Were and Bob McGrath.

The first time Colin Mansfield saw the Rolling Stones, he was 14 years old. Unlike other 20th-century kids, he didn’t have to wait in line for hours to score a ticket. Nor would he ever know the experience of his 21st-century counterparts, who would learn the hard way that the secret to hearing “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction” echoing off the luxury boxes in a concrete football stadium was a perfectly timed mouse click, accompanied by a boatload of cash.

“Apart from Brian Jones, they all seemed like immature assholes.”

Instead, Colin was invited to his first Stones concert by his oldest brother, John, who from 1959 to 1967 ran a string of music clubs in the Thames Valley west of London with an Army buddy named Philip Hayward. Initially, Mansfield (a sax player) and Hayward (a trumpet and trombone guy) promoted jazz concerts on Sunday nights in the “function room” of a small Windsor hotel called the Star and Garter. Beginning in the summer of 1962, they branded these shows as “Ricky-Tick” productions, and by December, the duo’s repertoire as promoters had expanded to include rhythm and blues and rock ’n’ roll, first with Alexis Korner on December 7, then with the Rolling Stones on December 14.

The Rolling Stones performing at Studio 51 Club in Great Newport Street, London, April 14, 1963. Brian Jones (left) and Keith Richards (right) would not play their guitars while sitting down for long, while Jagger would learn to get more animated on stage. Photo by Mark and Colleen Hayward/Redferns.

All these years later, Colin isn’t exactly sure when he first heard Brian Jones, Mick Jagger, Keith Richards, Bill Wyman, and Charlie Watts play covers of Bo Diddley, Muddy Waters, and Chuck Berry tunes, but he thinks it may have been on May 3, 1963. At the time, the Stones had just kicked their keyboard player, Ian Stewart, out of the band at the insistence of their new manager, an aspiring young kleptocrat named Andrew Loog Oldham, who stole the band away from their first manager, Giorgio Gomelsky, and prompted Stewart to famously say, “I wouldn’t piss on him if he was on fire.” On May 3, the group was still a week away from recording their first single, Chuck Berry’s “Come On,” which would be released about a month after that. As for “Satisfaction,” fans wouldn’t “Get No” for two long years.

Whatever the actual date of his first Rolling Stones show, Colin recalls the Star and Garter as being absolutely packed. There was no place for the young man to stand, let alone sit, so another older brother, Peter, picked out a spot for him on the stage. “It was made out of bits of plywood with some beer crates underneath it,” Colin clarifies during a Zoom call recently. “But I was happy to sit on the side of the stage watching Charlie Watts because I wanted to be a drummer.”

Guitarist Alexis Korner and singer Cyril Davies are credited with starting the R&B revival movement in the U.K. For this 1962 session at the Ealing Club in London, future Rolling Stones drummer Charlie Watts is sitting in. Photo by David Redfern/Redferns.

Though more than half a century has passed since that fateful day, Colin remembers it well. “They weren’t the Rolling Stones people know today,” he says, “but the essence of what they were, the thing that got them going, the thing that motivated them, that was there right from the beginning. There was no original material,” he adds, “so I suppose that would be a big difference.”

Another difference certainly was the quality of the sound. “Everyone played through individual amplifiers,” he says. “The PA system, if they had one, would only have been for the vocals, and forget about monitors for the musicians. I never saw monitors at Ricky-Tick shows.” Contrast that with a recent, pre-covid-19 Rolling Stones world tour, which required three 747s to get the band, its gear, and 300 employees from Point A to Point B.

All told, the Stones would perform some 40 times at Ricky-Tick clubs between December 1962 and September 1963, with at least 15 of those shows occurring before the release of “Come On.” From that first Ricky-Tick gig on December 14, at a time when the band was still enduring scattered boos from sparse crowds in London, the Stones always enjoyed enthusiastic audiences at the Star and Garter in Windsor, the Town Hall in Maidenhead, the Olympia Ballroom in Reading, and the Wooden Bridge in Guildford, all under the banner of Ricky-Tick.

On April 15, 1963, The Rolling Stones played two Ricky-Tick gigs on Easter Monday. Photo courtesy As You Were and Bob McGrath.

After many of these shows, Mansfield and Hayward would take the group’s members to dinner, during which the Stones would chow down as if they hadn’t had a proper meal in days, which was often the case. On occasion, Mansfield and Hayward even loaned the guys money. Mostly, though, Ricky-Tick provided the Stones with the crowds that made Oldham eager to saddle the naive lads with a usurious management contract, as well as an equally parasitic record deal with Decca. Ah, the sweet rank of success.

Last summer, this unflattering Rolling Stones origin story, along with many other juicy, anecdote-laden tales of the early days of British rock ’n’ roll, appeared in John Mansfield’s episodic memoir, As You Were, which was edited, co-written in places, and self-published by John’s aforementioned youngest brother, Colin; another Mansfield sibling (there are four), composer and arranger Keith Mansfield, provided the seed money for the labor of love. Happily, the book’s release party occurred while John, in frail health, was still around to enjoy the accolades and affection of friends and family. About a month later, John Mansfield died at the age of 81.

As You Were tugs at two primary threads—John Mansfield’s friendship with, and eventual estrangement from, his best friend Philip Hayward, and the evolution of British rhythm and blues into the various flavors of rock ’n’ roll we know today.

Philip Hayward (left) and John Mansfield at the Clewer Mead Ricky-Tick, Windsor. Photo courtesy As You Were and Bob McGrath.

To help readers understand that first thread, Mansfield supplies readers with countless examples of the adolescent practical jokes they both loved, particularly from their Army days, regardless of how much trouble their japes caused. For example, there was the time Mansfield was summoned to his sergeant’s office and showed up dripping wet from a shower, wearing naught but a towel, which, of course, ended up on the floor. Ever the literalist, Mansfield had been tardy to a previous summoning by the same no-nonsense superior, prompting the sergeant to tell him, “If I, or any NCO or officer, wants to see you, stop what you are doing and come immediately. Understood?” Yes, sir!

“Mansfield devotes a fair number of his book’s early pages to evidence supporting Hayward’s reputation as a serial fornicator.”

Hayward, too, loved pranks, especially when it afforded an opportunity to thumb his nose at authority, which is one of the many reasons why the two got along so well. As the trumpet guard of the 13th/18th Hussars, Hayward was obliged to blow the calls that, for example, summoned officers to mess for meals. Naturally, Hayward resented the regimentation of having to play a call at a precise time and place—when he was not resenting his duties, he was often barely able to perform them because he was so drunk. On one occasion, when protocol demanded that he perform a call in the snow, he deliberately loosened the mouthpiece of his trumpet so it would fall from his instrument and sink into the powder. That caused a delay in Hayward’s duties until the mouthpiece could be found, and a second delay until it could be warmed up enough to be playable. If Hayward was going to suffer, the duty officer barking commands at him would be made to suffer, too.

Cards and flyers from various Ricky-Tick venues. Photo courtesy As You Were and Bob McGrath.

Mansfield also devotes a fair number of his book’s early pages to evidence supporting Hayward’s reputation as a “serial fornicator,” as Mansfield describes him. We learn, for example, that on Hayward’s 21st birthday, Mansfield gave his friend a gross (144) of Durex condoms, which Hayward dryly declared “should last at least a couple of months.” And when the two rented a Windsor mansion by the Thames called Clewer Mead, which became home to Ricky-Tick shows from 1964 to 1966, Hayward carpeted his bedroom in mattresses, wall to wall.

Pranks and promiscuity aside, As You Were also details England’s early embrace of American rhythm and blues and rock ’n’ roll, as performed in the U.K. by the likes of John Mayall, Eric Clapton, Eric Burdon, and Manfred Mann. Mansfield also shares stories of the musicians who never made it big on the other side of the pond, including Alexis Korner, Cyril Davies, Georgie Fame, Graham Bond, and Hogsnort Rupert.

The first Ricky-Tick show to go outside the boundaries of jazz featured Alexis Korner’s Blues Incorporated, which included Graham Bond on organ, Jack Bruce on bass, Ginger Baker on drums, and Dick Heckstall-Smith on tenor sax. Photo courtesy As You Were and Bob McGrath.

If that last name doesn’t ring any bells whatsoever, how about Bob McGrath? Still nothing? Well, that’s not too surprising since Bob McGrath, who performed as Hogsnort Rupert, was just one of the many coulda-been-a-contender R&B performers who was in the right place at the right time, but, alas, nothing more than that.

Consider just a few of McGrath’s brushes with greatness. Early on, in 1963, McGrath sat in for singer Terry Brennan of the Roosters, which was the very short-lived band—13 performances, at least three of which occurred at Ricky-Tick clubs—featuring Eric Clapton on guitar before he joined the Yardbirds and John Mayall. McGrath’s own group, Hogsnort Rupert and the Good Good Band, toured R&B clubs all over England, from Newcastle in the north to Brighton in the south. “We were never very popular in the Ricky-Tick clubs,” McGrath says. “We were bigger in the north. Our horns didn’t cut it as much in the south,” he explains of his band’s pair of sax players. “Harmonicas and guitars were what people really wanted.”

The first appearances of Bob McGrath’s singer “shouting” the blues were on cards printed for Hogsnort Rupert’s first show. Photo courtesy As You Were and Bob McGrath.

For a while, the Good Good Band performed every Friday at the Marquee in London as the warm-up act for “Ready, Steady Radio,” a live weekly BBC radio show. “We never knew who was going to be featured on the live portion,” McGrath remembers. “Once I was doo-wopping with a great bunch of guys in the green room. They were so good, I offered them a job to join our show on the road. ‘You think we could make it, mon?’ one of the singers responded in a heavy Jamaican accent. Just then, they were announced. ‘And now, ladies and gentlemen, The Temptations!’ I was so embarrassed.” Apparently, The Temptations had been joking around with accents that day, and had McGrath completely fooled.

McGrath not only performed at Ricky-Tick clubs, he designed most of the posters, flyers, and cards printed to publicize Ricky-Tick shows. Many of these flyers depicted an image that McGrath had sketched of a Black man’s face “shouting” the blues. (More recently, he and his company, Eyeball Productions, designed As You Were.)

“I think I based it on a photo of Big Joe Turner,” McGrath says when asked about the image’s source, “probably from an album cover. I can’t draw that well,” he admits, “but that was something I could draw in seconds.”

Bob McGrath says he probably based his singer image on one or both of these 1950s Big Joe Turner albums, both of which he owned. Album images via Discogs. Center image courtesy As You Were and Bob McGrath.

As a Ricky-Tick insider, McGrath had a front-row seat to the two threads of As You Were, experiencing firsthand the complicated relationship between John Mansfield and Philip Hayward. “They were just out of the Army,” McGrath says, “wild boys, although they were substantially older than us. John was the good cop, Philip was the bad cop. Philip cheated me out of money many, many times. He was a nasty, nasty man; charming to be with, and very funny, but stingy as hell. In contrast, John was too damn nice. For some reason, he gave lots of stuff away. He was not financially sharp.

“John was one of the nicest men I ever met in my life,” McGrath continues, “but there was something about him, like Inspector Clouseau. He talked too loud and was terribly accident prone. One night he came home from a show in Guildford. We were all living at Clewer Mead at the time. I heard this moaning outside. It was John, with a broken leg and arm. The taxi driver had left him outside and he was propped up against a tree. Turns out he’d fallen down the stairs earlier in the evening at the club. That sort of thing happened to John all the time.”

As a participant, McGrath also had an insider’s view of the birth of the British R&B scene. Of the Rolling Stones, McGrath is matter of fact. “They were good,” he allows. “Jagger couldn’t sing to save his soul, but Charlie Watts was one of the few English drummers who had any sense of rhythm. It was quite a shock to see their audiences clapping on the right beat, the 2 and the 4 instead of the 1 and the 3. Jagger and Richards had very little interest in anything other than themselves,” he concludes. “Apart from Brian Jones, they all seemed like immature assholes.”

The Sixth National Jazz & Blues Festival was held in Windsor from July 29-31, 1966, with production help from Ricky-Tick. Among the performers were Eric Clapton and Cream. Photo by David Redfern/Redferns.

McGrath also sheds light on why the Ricky-Tick clubs outside of London seemed so much more fun than the ones in the city proper. “London and Soho were mean streets,” he says, “even then. It was pretty seedy—drug people, gangsters—not a friendly place to be. I never felt at ease there, and I was there an awful lot.”

“One time my mother pushed Ginger Baker in the swimming pool in December.”

In contrast, the Ricky-Tick clubs that popped up in the cities and towns of the Thames Valley were welcoming places, notwithstanding the occasional punch-up between rival groups of mods and rockers. Beyond the more relaxed attitude that came with being outside of London, the U.K. in general warmly embraced music performed and/or composed by Black artists. Unlike in the United States during the early 1960s, when rhythm and blues records by Black performers were mostly listened to by Black audiences, white kids in England were fully on board. Thus, when Black performers from the United States such as Sonny Boy Williamson, John Lee Hooker, and Sister Rosetta Tharpe played Ricky-Tick, they were greeted by packed clubs filled with adorning fans, from the predominantly white locals to the Black American servicemen stationed at nearby U.S. Air Force bases in South Ruislip, West Ruislip, and High Wycombe.

One such American serviceman named Geno Washington was stationed farther away in East Anglia. After his tour of duty, he stayed in the U.K., formed Geno Washington and the Ram Jam Band, and ended up playing countless gigs in the Thames Valley. It didn’t take long for the Ram Jam Band to become a mainstay of the network of Ricky-Tick clubs.

Geno Washington and the Ram Jam Band also played the 1966 Windsor Jazz Festival. Photo by Caroline Gillies/BIPs/Getty Images.

Another insider from the Ricky-Tick years was Brea Gosling, who answered to Brenda Elsdon when she was Philip Hayward’s younger-by-a-decade girlfriend, from roughly 1962 to 1966. Brea and her younger sister, Sandra, who would later go out with Peter Green of Fleetwood Mac, lived with their parents, Cyril and Helen, and their brothers, Norman and Barry, in the nearby, upscale community of Stoke Poges. Born into a musical family, the two teenage girls had taken an interest in the Sunday night jazz shows at the Star and Garter, which is where Brenda met Philip.

“My father was a musician when he was younger,” Gosling tells me. “He played clarinet, saxophone, piano, and accordion, and he had his own trad-jazz band for a while. My parents were quite the party people,” she says. “Our house had a swimming pool and a bar, so after a lot of Ricky-Tick shows, many of the musicians would come back and jam at our house. Sonny Boy Williamson, Eric Clapton, Peter Green, Georgie Fame, Brian Jones, Gary Brooker, Graham Bond. We used to have lots of reclining chairs, all in red velvet. After they’d been playing all night at Ricky-Tick, some of the musicians would collapse in the chairs and say, Oh, Lord, take me, Lord. I just want to die here! One time my mother pushed Ginger Baker in the swimming pool in December,” she goes on. “It was freezing cold. I’ve never seen anyone go in and out of a pool so quick. But there was lots of free booze, so all was forgiven.”

Lest you get the idea that Gosling was merely a party girl, she quickly made herself indispensable at Ricky-Tick. “In the early days, I ran some of the clubs in Guildford and the Guildford area,” she recalls. “John and Philip would be somewhere else, so I’d go off with a couple of bouncers, the security men, and run the show.”

Sister Rosetta Tharpe played numerous Ricky-Tick shows. This one took place at Clewer Mead in Windsor on October 31, 1964. Backing her up was a local group called Five Dimensions. Photo courtesy As You Were and Bob McGrath.

Gosling was usually in charge of the money collected at the door. “I sat in a little sort of kiosk and just took in all this cash. We used cardboard boxes for the notes, and they would always fill up. At one point, Philip gave me a trombone case. I’d fill it with cash and hide it under my bed.”

One infamous event that Gosling ran was a Rolling Stones concert in the village of Worplesdon, just north of Guildford. The date was August 23, 1963, which means that by then, the Stones were no longer relying on Mansfield and Hayward for after-show meals. They now had a single in the U.K. charts, although it would only reach number 21. Still, the attention was clearly going to their heads. Earlier that same August day, for example, the Stones had appeared on a new ITV television program called “Ready Steady Go!”

No doubt the taping was exciting, but rather than meeting their contractual obligation to play for Ricky-Tick, which had printed posters for the event, taken out ads, and even hired buses to transport teenagers from Ricky-Tick’s previous venue in Guildford to nearby Worplesdon Village Hall, the Stones decided to blow off the gig and go to a London nightclub to celebrate.

Graham Bond is said to be the first Brit to play a Hammond organ through a Leslie speaker. Photo courtesy As You Were and Bob McGrath.

By the time Mansfield showed up at 9 p.m. to see how things were going (he’d been at a Beatles concerts in Guildford, passing out flyers for upcoming Ricky-Tick shows), the crowd was being kept amused with singalongs and party tricks. Literally. Mansfield decided to give everyone full refunds on the spot, paying out 20 pounds more than had been collected due to the confusion. In As You Were, Mansfield writes, “The Stones displayed their contempt for their fans by not appearing.” If Mansfield’s reaction was emotional, Hayward’s was businesslike, using the no-show as leverage to secure four more bookings from one of the band’s managers, which may, in a nutshell, sum up the difference between the two partners.

Gosling also left her mark on Ricky-Tick by launching a boutique, or a Bou-Tick as it was called, in the Windsor club at Clewer Mead. “I used to design clothes, plastic mini skirts, that sort of thing,” she says, “and I had lots of friends who were training at the London School of Fashion.” The Bou-Tick combined this homemade fashion with new pieces from London designer Mary Quant, plus an assortment of vintage items. “I decorated the place in black-and-white stripes, very Op-Arty, very, very trendy. Some of the bands’ girlfriends used to come in and buy things,” she says. Among other commissions, Gosling made a Victorian jacket for Eric Clapton, who wore it for a period on stage.

No doubt it was all great fun, but it was undoubtedly easier to attend a Ricky-Tick club than to help run it. “I ended up leaving Philip,” Gosling says of the middle of 1966. “It was all sex, drugs, and rock ’n’ roll, all the time. He was becoming a real womanizer, while I was being totally faithful to him. It wasn’t good for me, so I finished it.”

An assortment of screenprint posters for Ricky-Tick. Instead of silk, Mansfield and Hayward purchased organdy for their screens. When stores ran out of that, they used curtains, as was the case for the Rolling Stones poster. Photos courtesy As You Were and Bob McGrath.

That, in turn, gave Gosling a chance to experience the swinging sixties for herself. “All these different people had been after me, so I thought, Alright, I’m going to enjoy life now. I went out with Paul McCartney’s brother, Mike McGear, who was in The Scaffold for some time. And then I went out with Chas Chandler of The Animals.”

Chandler had been chafing in his role as Eric Burdon’s bassist—he wanted to be a manager. And so, it was from Chandler that Gosling learned, perhaps before anyone else in England, that a force of nature that would change the rock-guitar landscape forever was heading to the U.K.

“He phoned me from America,” she recalls, “at 3 o’clock in the morning, and said, I found this amazing guy who plays guitar with his teeth. And I said to him, What are you on? Of course, it was Jimi Hendrix.” By November 26, 1966, Hendrix was playing the Ricky-Tick in Hounslow, accompanied by Georgie Fame’s former drummer, Mitch Mitchell, and a guitarist named Noel Redding on bass. Hendrix would play numerous other Ricky-Tick gigs in the early spring of 1967, in Hounslow, Newbury, and Windsor.

Lee Dorsey (“Working in the Coal Mine”) and John Lee Hooker (“Boom Boom”) are just two of the American R&B and blues acts who performed at Ricky-Tick. Photos courtesy As You Were and Bob McGrath.

If all Ricky-Tick was remembered for was the launch of the Rolling Stones, Jimi Hendrix, and the birth of British R&B, that would be more than enough to secure it a place in rock history. But Ricky-Tick was also an early breeding ground for Cream (take one part Eric Clapton of the Roosters, Yardbirds, and John Mayall, add the Alexis Korner and Graham Bond rhythm sections of Ginger Baker and Jack Bruce, shake vigorously).

Unforgettably, Ricky-Tick clubs hosted many early Who performances, including one that devolved into an epic onstage fight between guitarist Pete Townshend and drummer Keith Moon. Rod Stewart played harmonica at Ricky-Tick with Jimmy Powell and the Five Dimensions before joining Long John Baldry and the Hoochie Coochie Men; Stewart was also in a group called Shotgun Express, which featured Peter Green on guitar and Mick Fleetwood on drums.

Pink Floyd played some of their earliest gigs at Ricky-Tick, as did Elton John, back when he still went by Reggie Dwight and played piano with a band called Bluesology, which, among other things, backed up visiting American artists such as Patti LaBelle and Billy Stewart when they performed at Ricky-Tick.

By 1967, Ricky-Tick was hosting some of the biggest names in rock. Photos courtesy As You Were and Bob McGrath.

Did we mention Ben E. King singing his hit “Stand By Me,” Little Stevie Wonder doing “Fingertips” at the age of 14, guitar genius John McLaughlin sitting in with Georgie Fame and Graham Bond, and the use of Ricky-Tick atmospherics for a scene in the 1966 art film “Blow Up,” in which Jeff Beck of the Yardbirds destroys his guitar on stage à la Pete Townshend (who was supposed to perform the part but didn’t) while Jimmy Page, also on stage, looks on? Consider them mentioned.

After the two-year lease at Clewer Mead ran out at the end of 1966, Mansfield and Hayward continued to promote shows at their satellite spaces around the Thames Valley, but by the summer of 1967, rock ’n’ roll was becoming a big business, with risks and revenues that were too great for cardboard boxes and trombone cases to handle. Still, their years of experience doing Ricky-Tick shows should have given Mansfield and Hayward a leg up on the new crop of impresarios determined to make Andrew Loog Oldham look like an amateur. In fact, Hayward did just fine after Ricky-Tick, opening a club called Pantiles in Bagshot.

“Philip really wanted John to go in with him,” Gosling says, “but sadly, John had spent all his money. He didn’t have the resources to get involved.”

Pete Townshend performing with the Who at the Ricky-Tick co-produced Windsor Jazz & Blues Festival in 1966. Photo by David Redfern/Redferns.

In As You Were, Mansfield writes that he wanted to continue doing shows under the banner of Ricky-Tick, but that Philip wouldn’t agree to let him use the name on his own. Reading this part of the book, one wonders why Mansfield didn’t simply do it anyway.

“I know, I know,” Gosling agrees. “But I think John had a loyalty to Philip that prevented him from taking that step. Besides,” she says, “John didn’t have the money to keep doing Ricky-Tick on his own, and I think he needed Philip’s organizational skills. John was terrible at organizing anything.”

In the end, Mansfield’s almost heedless generosity was his undoing. “One of the first things I remember about John,” Colin tells me, “was when he came back from Germany, where he’d been posted in the Army. He brought me one of those wooden toboggans with the metal runners—a proper one, not a plastic one. I’d never seen one like that before; John carried it on his back all the way from Germany for me.”

Later, observing his youngest brother’s interest in drumming, John would give Colin the money to buy himself a drum set, paid for with his earnings from Ricky-Tick. “I took it for granted,” Colin says. “I guess I thought, That’s what your oldest brother does. Same thing with the club. Sitting on the stage with the Rolling Stones? That was normal to me because that was what my brother did. At the time, many of us took so much for granted,” Colin says. “Ricky-Tick and the rest of it; it was just what was going on. But John, he was a beautiful, beautiful brother.”

To order a copy of As You Were, visit RickyTick.com. To listen to Brea Gosling’s radio show about the music scene, visit Brooklands Radio. You may also enjoy learning about the musical exploits of the next generation of Goslings at Goldun Egg. And fans of blues, soul, zydeco, and gospel should check out the discographies at Eyeball Productions. And on August 8, former Ricky-Tick DJ Martin Fuggles will be participating in Retrofestival.

Hippies, Guns, and LSD: The San Francisco Rock Band That Was Too Wild For the Sixties

Hippies, Guns, and LSD: The San Francisco Rock Band That Was Too Wild For the Sixties

Battle of the Ax Men: Who Really Built the First Electric Rock 'n' Roll Guitar?

Battle of the Ax Men: Who Really Built the First Electric Rock 'n' Roll Guitar? Hippies, Guns, and LSD: The San Francisco Rock Band That Was Too Wild For the Sixties

Hippies, Guns, and LSD: The San Francisco Rock Band That Was Too Wild For the Sixties A Garage Sale Find of Rare Beatles Photos Took a Collector on a Magical Mystery Tour

A Garage Sale Find of Rare Beatles Photos Took a Collector on a Magical Mystery Tour Rolling Stones RecordsLike the Beatles, the Rolling Stones began releasing vinyl records when it …

Rolling Stones RecordsLike the Beatles, the Rolling Stones began releasing vinyl records when it … Pink Floyd RecordsWhen Pink Floyd fans talk about their favorite band, invariably the discuss…

Pink Floyd RecordsWhen Pink Floyd fans talk about their favorite band, invariably the discuss… Jimi Hendrix MemorabiliaNo guitarist put the fear of God into his peers like Jimi Hendrix. Born in …

Jimi Hendrix MemorabiliaNo guitarist put the fear of God into his peers like Jimi Hendrix. Born in … Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

I am a marketing student with a very tedious research project that I need to finish before I can graduate. I have to select a rock band from the past, research show dates, then begin locating concert ads and promotional items used to promote the shows. A comparison of marketing from the past until now.

The band I selected is THE WHO. I am searching high and low for the concert advert of this show:

May 21, 1965 @ Ricky-Tick Club, Guildford

Do you possibly have this concert advert? I am desperately trying to find it to almost be done with May 1965 portion of the project. Thank you!

Colin says: “Check out the rickytick.com web site. There is a really good gig list there and on the Guildford page for May ’65 there is a programme card which includes the Who gig. These tended to be not much bigger than the size of a playing card. I guess that must be the one being referred to.”