As a teenager growing up in San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury neighborhood during the mid-1960s, Mari Tepper might have been just another poster child for that colorful decade. Instead, Tepper designed many of the posters that defined it.

As a teenager growing up in San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury neighborhood during the mid-1960s, Mari Tepper might have been just another poster child for that colorful decade. Instead, Tepper designed many of the posters that defined it.

“My father knew some of the Committee people,” Tepper explains. “I knew them as my mother and father’s dope-smoking beatnik friends.”

Because her posters were widely distributed in 1967 and 1968 and their purpose was often to promote rock concerts, Tepper is largely known in the niche network of rock-poster collectors for this body of work, and little else. But a recent exhibition, also titled “Laying it on the Line,” which I helped curate for the Haight Street Art Center, introduced many of Tepper’s fans to more than half a century’s worth of her other work, from her figurative drawings and paintings to the sugar-glazed reliefs she pressed and kneaded from salty bread dough. Together, these mostly unheralded pieces, which have survived uprootings, a fire, and the water damage that ensued, reveal an artist whose pen is sharpest when spilling ink in the cause of social justice, equity, and human rights, whether to housing, mental health care, or one’s sexuality.

“My parents encouraged us to explore,” Tepper told me during one of our many conversations during the past year. Her mother, Adelina (known to friends and family as Addie) was a painter who studied at Yale and took her only daughter to street protests—both made a strong impression on young Mari Bianca Tepper. Her father, Gene, was also a painter, although he made a living as an industrial designer, founding a firm called Paradigm. Born in San Francisco in 1948, Tepper is the second of four siblings, following an older brother named Jesse and playing the role of elusive big sister to a pair of twins, Tony and Tim, who are six years her junior.

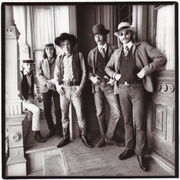

Top: “Hallelujah the Pill!!”, 1967. Above: The Tepper siblings in San Francisco. Clockwise from left: Mari, Tony, Tim, Jesse.

Tim Tepper remembers well his sister’s unconventional approach to making things. “Early on,” Tim tells me, “when there were demonstrations against the Vietnam War, Mari made what she called her Napalm babies. They were basically Barbie dolls that were kind of melted together. Obviously kind of awful, but also sort of funny.”

By the time Tepper graduated from Lowell High School in 1966, she had already designed posters for theater companies and rock bands. The former was an improv-comedy group called the Committee, whose 300-seat theater at 622 Broadway in the North Beach neighborhood had been the site of the first San Francisco performance by the Charlatans on August 30, 1965, which makes the Committee an early, if short-lived, site for the sort of music that would soon pack venues like the Avalon Ballroom and the Fillmore Auditorium.

“My father knew some of the Committee people,” Tepper explains. “I knew them as my mother and father’s dope-smoking beatnik friends. I think they thought it was cute that this young person could come up with these very creative ideas for them.” Tepper’s design work was probably also appealing to her parents’ pals because they never had to—or, at least, they assumed they never had to—pay Tepper for her work.

Printing plate for a Mari Tepper poster designed for a concert by jazz musician Charles Lloyd at the Committee theater on January 23, 1966. Image via Heritage.

Tepper’s first rock poster advertising a concert in a major venue was a black-and-white drawing she created for the Mojo Men, the Vejtables, and the Hedds at Winterland on May 6 and 7, 1966, just before she graduated from Lowell High School. In it, a six-fingered woman’s voluminous black dress serves as the background for Tepper’s hand-drawn, blocky white lettering, while the detail in the woman’s hair and the chair upon which she sits foreshadows the fine lines that would fill Tepper’s drawings for decades to come.

Due to her artistic precociousness, Tepper became something of a celebrity in the Haight, where she continued to live after graduating from high school. It was Tepper who, in 1966, created the famous “Free Frame of Reference” installation on the façade of a Diggers location that year (you can see a photograph of Chocolate George of the Hells Angels standing in front of Tepper’s installation here). By the end of the year, Tepper had created illustrations for the Oracle, an influential underground newspaper that had been founded in the Haight in the fall of that year. Contributing to the Oracle put Tepper in the company of the counterculture luminaries such as Timothy Leary and Allen Ginsberg, who were featured in the paper’s pages, and rock-poster artists like Rick Griffin, who did a number of the paper’s covers. In 1966,Tepper’s work also appeared in exhibitions at the San Francisco branch of Berkeley’s Print Mint, as well as the Haight’s own Psychedelic Shop.

Tepper was still in high school when she designed her first poster for a concert at Winterland. These shows took place on May 6 and 7, 1966.

At times, the young artist’s success created tricky dynamics at home. “My ego was kind of blown out of proportion pretty early on,” she says of her state of mind during those years. “I felt like the star in the family. I was clearly the one who was achieving a certain kind of success that no one else was.” With her siblings, that is; her parents were another matter. “I never felt competitive with my mother,” Tepper says, “but I was aware that I did not think I should be successful on a certain level as long as my father was well known for his work.”

At other times, there were no dynamics at all, tricky or otherwise, for the simple reason that there was a period when Tepper didn’t really have a home. “My mother took my twin brothers out of school for a year,” she explains. “They traveled around Europe, to Morocco, all sorts of interesting places. My parents had already split up, so I was sort of left fending for myself. I did a lot of couch surfing, but I was homeless, really.”

According to Tim Tepper, the same sort of thing happened to him and his twin, Tony, during their last year at Galileo High School, by which time their mother had moved to Montreal and they were nominally living with their father. “He was pretty much an absent parent and out of the picture at that point,” Tim recalls. “I remember a lot of times, we were just on our own. He thought it was better not to give us any financial support,” Tim adds, “because he believed it was good for us to learn independence.”

This Tepper calendar for 1967 was printed at Double-H Press in the Haight and funded by local merchants.

By the time 1966 had become 1967, Tepper’s career was ascending. She began the year with the release of an orange one-sheet calendar printed at Double-H Press in the Haight and paid for by some of the “new merchants and craftsmen in Haight Ashbury,” as the credit at the bottom of the calendar reads. Double-H was a local like Tepper, and through her work at the press, she became friends with its owners, Robert and Jennie Hill, who had admired some of the drawings in Tepper’s sketchbooks. In 1968, 18 of those drawings would be selected by the Hills for printing as postcards, which were sold to the tourists who were then flooding the Haight.

In the spring of 1967, Tepper designed a black-and-white poster for a concert at California Hall, her figures rendered almost as silhouettes against a black background. That summer, she produced a poster for the Haight’s own Straight Theater, and in October she drew and lettered two posters for shows featuring Big Brother and the Holding Company and Quicksilver Messenger Service, one being a benefit for the newly formed Haight Ashbury Free Clinic, the second featuring a hippie’s Holy Grail lineup at Winterland—in addition to Big Brother and Quicksilver, the Grateful Dead played a set.

But Tepper’s most acclaimed poster of 1967 bore no legendary band names, focusing instead on a preoccupation of the times that was even more important than music—sex. Little wonder then that today Tepper is still best known for her “Hallelujah the Pill!!” mandala, which depicts a quintet of brilliantly hued couples demonstrating various sexual positions. Not surprisingly, this psychedelicized update of tantric sex sold tens of thousands of copies in headshops around the country. But as with her work as a high-school student for the Committee, and her later Haight-Ashbury postcards, Tepper saw nary a dime.

Unlike male poster artists, whose work tended to objectify women’s bodies, Tepper treated the anatomy of the women in her posters as organic rather than titillating elements, as seen in this composition for a 1967 concert at California Hall.

With its rich colors and intricate geometrics inspired by the work of Austrian artist Friedensreich Hundertwasser, the composition of “Hallelujah the Pill!!” revolves around a birth control pill dispenser bearing Tepper’s hand-lettered days of the week. Tan, banded snakes, some sporting two heads, slither behind the couples, whose long legs and slender torsos radiate from the pill dispenser to form a five-pointed star. Because its title is repeated on all four of its 22-inch sides, the poster could be read in four different ways and still convey its message. In part, this all-sides-up fluidity was a playful riff on a design maxim of her father’s, whose experience as an industrial designer had taught him that an object succeeded most when it could be approached, and used, from any direction. In “Hallelujah the Pill!!” Tepper took her father’s teachings literally. “Well, you’ve got to have some fun,” she says today with a smile.

The circumstances surrounding the creation of “Hallelujah the Pill!!” are less sunny, offering an unsettling glimpse of the charged sexual and social atmosphere of the Haight during the Summer of Love that’s wildly at odds with the happy-go-lucky flower-child images that fill our collective nostalgia. According to an interview with Madeleine Morley published in 2018, Tepper remembers designing “Hallelujah the Pill!!” on the floor of an apartment she shared with a friend. Tepper was 19, her roommate was just 16, and that girl’s boyfriend was a 20-year-old named Bobby Beausoleil, who was trying to recruit Tepper’s young roommate to join his friends in the Manson family, even as he was trying to seduce Tepper.

Fortunately, neither woman succumbed to Beausoleil’s creepy advances; two years later, Beausoleil would be arrested for murder at the height of Helter Skelter hysteria, and he is still serving a life sentence for his crime. As Tepper told Morley, Beausoleil stood over her while she worked—we can practically picture him licking his lips—as she painted copulating couples in vivid Luma dyes. “I was sitting on the floor doing this poster, which was very erotic, so it made me feel quite vulnerable,” she said.

Left: In 1967, Tepper designed several rock posters for shows headlined by Big Brother and the Holding Company, including this benefit for the Haight Ashbury Free Clinic. Right: This Albert King poster from 1968 is one of two Tepper posters in the first Bill Graham numbered series.

In contrast, Tepper felt completely at ease with Bill Graham, for whom, in 1968, she designed her only two posters in the impresario’s first numbered poster series (BG-117 and BG-118). Tepper could have continued to work for Graham, whom she has described as both “kind” and her “first boss,” but by the end of that year, Tepper had left San Francisco for a place outside Santa Fe, New Mexico. Having brushed off a member of the Manson family the year before, Tepper now found herself in the thrall of a charismatic alpha-male musician named George Eade, who demanded that she leave behind all her worldly possessions, including lots of now-valuable artwork. “He made me get rid of my posters as proof that I was going with him to be his girlfriend,” Tepper says.

When asked why at the height of her success she decided to pack it all in and follow some guy to rural New Mexico, Tepper usually remarks that Eade was handsome, comparing his looks favorably to George Harrison’s. Lennon and McCartney’s greater popularity among teenage girls aside, Tepper was also tiring of the Haight, which, she believed, was changing for the worse. “There was a lot of very magical stuff going on,” Tepper told Morley in that same 2018 interview, “but I wasn’t happy with a lot of things taking place, like when the Hells Angels came into the Haight in late ’67 and brought in speed and all kinds of other freaky stuff.” Eade offered Tepper the promise of a drug-free idyll away from San Francisco’s increasingly mean streets.

Eade may have also offered Tepper an alternative to the “We can share the women, we can share the wine” ethos that preceded the feminist movement of the 1970s—yes, we are aware that these Grateful Dead lyrics were not sung until 1971, but they capture the way many men, even the seemingly sensitive ones with flowers in their hair, objectified women in the 1960s. “At the time,” Tepper recalled, “being a woman was not as fun as being a man. The ‘make love not war’ thing was taken very literally.”

The cracks in this Tepper bread sculpture from the early 1970s are evidence of the fragility of this medium of necessity, which she used extensively during her New Mexico years.

In the end, though, Tepper may simply have been weary of trying to make it on her own so soon after finishing high school. “I was tired of not having anybody take care of me,” she tells me. The move to New Mexico, she says, “sounded like I was going to be taken care of, so I was willing to give up my stuff, and my stuff was all my artwork.”

Unfortunately, the arrangement also demanded that she give up a good deal of her personal freedom. According to Tepper, Eade mostly wanted her in the kitchen, and he refused to allow her to fire up the wood stove to heat their modest dwelling, even during the winter when low temperatures routinely dipped into the teens. “Baking art,” as Tepper calls the making of her bread-dough sculptures, was therefore a strategy to stay warm and keep busy. Best of all, she could purchase her primary materials—flour and salt—with food stamps.

As in sync with the zeitgeist as her posters had been in the Haight Ashbury of the 1960s, Tepper’s breadworks were similarly in tune with their place and time. As it turned out, Eade had been onto something when he decided to give up the city for the country; the year he and Tepper tramped off to New Mexico, the first issue of the Whole Earth Catalog was published to help people like them make lives for themselves as they went “back to the land.” In that context, making art out of bread dough was an extension of this impulse, and a number of Santa Fe curators agreed, selecting Tepper’s work for exhibitions in 1969 and 1970.

Tepper often captioned her work, as in this mixed-media piece from the early 1970s.

In retrospect, Tepper’s bread sculptures seem an improbable second act. After all, their form and content had little in common with Tepper’s posters advertising performances by rock bands or thanking the heavens for oral contraceptives. But both utilized figures arranged in odd worlds of Tepper’s making. As with her drawings, Tepper packed her doughy figures into tight, crowded spaces, while the colors she achieved were every bit as arresting in three dimensions as they had been in two.

By 1974, Alexandra Jacopetti had included Tepper’s bread-dough sculptures in her influential book, Native Funk & Flash: An Emerging Folk Art. Tepper only got two pages, but on one of them Jacopetti shared Tepper’s recipe for sculptural bread dough: “Mix four parts flour to one part salt, add water to get the desired consistency, sculpt away, bake in a moderate oven, paint with sugar glazes or acrylic paints and varnish over the whole thing.” Unfortunately, the ratio of salt to flour in the recipe pretty much guaranteed that the sculptures would eventually self-destruct, which most of them did.

New Mexico is also where Tepper brought her only child into the world. Born in late 1971, Angus Eade mostly lived with his mother before the boy’s father assumed custody of him in 1977. In between, Tepper and her son returned to San Francisco in 1973, while Eade found a place an hour or so north.

A flyer featuring a breadwork, identified as a “sculptural painting,” advertised a Tepper exhibition at the Ames Gallery in Berkeley, 1976.

Upon her return to San Francisco, Tepper had a number of shows at a number of galleries, including the Canessa Gallery, the Ames Gallery, and Art for Arts Sake. That exhibition was reviewed in the San Francisco Chronicle. “He gave me a sort of back-handed compliment,” Tepper says of the reviewer, who praised her drawings but dismissed her bread sculptures as folk art. “It was a huge show,” she continues, “and I wasn’t ready to be showing that much stuff. I didn’t have a clue. I couldn’t bring myself to put prices on anything, so when it came down to people wanting to buy stuff, I’d say, ‘Oh, that one’s in my private collection.’ At the time, I was very self-absorbed, not a person who could be advised. I didn’t know what I wanted, so I kind of screwed myself.”

For Angus, whose decision to chart a career in architecture was strongly influenced by his grandfather, Gene Tepper—“He’d tell me stories about Charles and Ray Eames,” Angus recalls—his childhood days with his mother still evoke fond memories, even though the time he got to spend with her was sometimes irregular, and would soon be tightly controlled by his father.

“We were living on Columbus Avenue above Graffeo Coffee, across the street from Washington Square Park,” Angus says of the apartment he shared with his mother in North Beach. “The whole interior had been created by Mari and company, her friends and other artists. The bed I slept in was like a kind of fairy-tale house that a carpenter friend of hers had built; it was like a bunk bed that was on the roof of this small house that was inside my room. Her apartment was very quirky.”

Even though she never married, Tepper signed many of her pieces from the early 1970s with the last name of her common-law husband, George Eade.

According to her brother Tim, Tepper struggled as a mom. “Mari had a very rough time raising Angus,” he says. “I mean, this is just my take, but I think that she kind of wanted to have her regular life and also be a mother.” In fact, during 1975 and 1976, Tepper visited Los Angeles for about three weeks to pursue design work for record companies (she did a few album covers), leaving Angus in the care of his father, who soon asserted his paternal right to the child—the arrangement was never legally binding, but for Tepper, challenging the arrangement was more than she could muster.

“When I was five or six,” Angus continues, “when I started living with my dad and could only visit my mom, we would go to cafes and draw together. I don’t remember the name of this place in the Castro, but I can picture it. We’d just draw, being very quiet and kind of observing each other and admiring each other’s work, that sort of thing. That’s what we did, and I loved it. I’ve drawn by myself like that to get into a quiet kind of space ever since. In fact, that’s what I’m doing right now.”

To make sense of the custodial loss of her child, Tepper also drew, although there was nothing quiet about it. Instead, Tepper scratched out a frenetic, six-page comic called Myrrtle and Purrlee. Unpublished until her exhibition this year at the Haight Street Art Center, Myrrtle and Purrlee mutates selected circumstances of Tepper’s relationship with Eade and their son into semi-autobiographical fiction that’s filled with marvelous wordplay and scores of detailed drawings, none of which make any attempt to set the record straight. In Myrrtle and Purrlee, Tepper, who was signing her work “Mari Bianca” at the time, is Myrrtle, which she sometimes spells as Murrtle; Eade is a character named Hermann (pronounce it as two words for full effect); and Angus is depicted as their daughter, Purrlee. All are drawn as cats.

Myrrtle and Purrlee

Having felionized her family and changed the gender of her real-life son, Tepper begins the comic by recounting Myrrtle’s first meeting with Hermann, a randy tomcat who essentially breaks into Myrrtle’s bedroom by climbing through an open window while she paints; a Betty Carter record is playing in the background. “She was tired of being bugged by this drip,” we read of Myrrtle’s initial assessment of Hermann, “but his approach was unique, very conceptual.” As in real life, it worked: “Yeah, she fucked him,” Tepper writes. “She had her plan in action, her wheels in gear.”

That plan included giving birth to Purrlee, making sure Purrlee and Hermann were compatible, and then leaving her beloved kitten in the tomcat’s capable paws for 14 years, a deliberately gross exaggeration, perhaps, of her brief visit to L.A. a year or two earlier. “Hermann was ready,” Tepper writes, describing Hermann as “the real better half” of their relationship “and a domestic wonder at that.”

Even if we can never actually know Tepper’s state of mind in 1977, we can assume that she could not possibly have believed these statements to be true. Beyond what we know from Tepper and her son of the actual events of their lives at that time, the clues in Myrrtle and Purrlee are the numerous occasions when Tepper’s pen becomes a knife. “He lived up to all her expectations,” Tepper has Myrrtle sarcastically say. On page three of the comic, Hermann reads a letter from Myrrtle that heaps him with similarly disingenuous praise: “You have been the best wife anyone could wish for,” Myrrtle writes, adding, “It is your art.” Such jabs masquerading as compliments fill Myrrtle and Purrlee.

A small, untitled painting by Mari Tepper, probably from the 1970s.

By page four, Myrrtle returns from her “search for the 4th primary color” to show Purrlee “the real world,” and how to live “the life of a truly outside kat.” To this end, “Myrrtle introduces Purrlee to her most innovative friends,” analogues, we can fairly guess, for people such as the actual carpenter who built Angus’ bed. In the end, Hermann becomes a professional wife after overcoming the despair caused by the loss of Purrlee, this time at Myrrtle’s hand. For her part, Purrlee follows in her mother’s artistic footsteps by starting a band called Spare Change. On page five we learn that every year on July 29, the family reunites to talk of their lives and futures, each “content with their own specialness.” In fact, Angus’ childhood was wrenching for both the boy and his mom, but in case you’re wondering, these days the two speak regularly by phone, so at least part of the comic’s happily-ever-after ending has come true.

From the vantage point of 2022, Myrrtle and Purrlee can be seen as both an act of catharsis on the part of the artist as well as a turning point in the look of her work. Prior to the comic, Tepper’s lines flowed and looped amid compositions that were casually surreal and often awash in color. Her style was almost an anti-style, in which imperfect circles, wandering lines, and assorted squiggles and marks were left to coalesce—or not—as they pleased. When they did, they often animated themselves into distinctive, sometimes androgynous, characters right before our eyes, albeit ones often sporting too many fingers, toes, and breasts.

In general, Tepper tended to strip her drawings to their essentials—line and form—to produce a unique sensibility that could swing from the macabre to the whimsical, often within the same figure or groups of figures. This ocular alchemy has always been one of Tepper’s many gifts, but it is also the product of diligently practiced dexterity. Her work may look loose, at times even out of control, but the surprising ways in which her compositions come together has never been an accident.

“She’s left-handed,” Angus adds, “but also ambidextrous. She could probably draw with her feet. In fact, I think she can.”

In the late 1970s, Tepper often created portraits of performers such as writer Ntozake Shange reading at the Intersection (left) and saxophonist Jackie McLean playing at the Keystone (right).

After Myrrtle and Purrlee, Tepper’s work became more angular, jagged, impatient, urgent. Not always, of course—with Tepper, it’s never one thing or the other. For example, many of the late-1970s sketches she made of jazz musicians such as Jackie McLean and Pharoah Sanders performing at the Keystone Korner in San Francisco, or poets such as Ntozake Shange reading at a gallery called the Intersection, are lyrical and cool. But as much as Tepper loved jazz and poetry and regularly responded to both via her art, she was also a bit of a punk, and much of her work from this period reflects the flyer-stapled-to-a-telephone-pole sensibility of that energetic scene.

As if the tumult in her life caused by her limited access to Angus was not enough, during this period Tepper was also trying to figure who she was sexually. It was her mother, Addie, who pushed her to give women a try. That turned out to be good advice, but in her art, Tepper eventually took the issue of sexuality beyond “traditional” so-called non-normative interactions by drawing a pair of gender-nonspecific line figures tangled in a fluid embrace with the words “Does It Really Matter Which Is Which” handwritten along the bottom edge of the pictorial frame. For Tepper, it seems, our very anatomy could be construed as a construct.

In “Does It Really Matter Which Is Which,” Tepper seems to suggest that anatomy itself could be a social construct.

In her “One Struggle” drawing from 1978, Tepper leveled the playing field even further by expanding her increasingly inclusive community to include a drag queen, a transgender person, and a figure with a cane, suggesting someone with a disability. “Stop Being Sad, Start Getting Mad” the poster advises its audience, which was supposed to be the readers of a gay-interest newspaper that had commissioned Tepper’s drawing. As such, “One Struggle” might have been prescient advice for that audience in the coming decade, when the AIDS epidemic and its effects would roar through San Francisco, but the newspaper shelved Tepper’s drawing for being too controversial, an anecdote that would have felt entirely at home in And the Band Played On by Randy Shilts. “One Struggle” was eventually published in 1990, reprinted in 2018, and made into a T-shirt in 2022, evidence of its enduring relevance as both art and social commentary.

During the 1980s and ’90s, Tepper became preoccupied by something more essential to her well being than her sexuality, or even jazz and rock ’n’ roll—her mental health. Characteristically, she eschewed the conventional role of vulnerable patient seeking help from authority-figure doctors offering a menu of canned cures and instead embraced a branch of mental health care that put the client’s perspective first. With her own experience as her resume, she became active in the Clients’ Rights Movement, co-founding the Spirit Menders Community Center in 1984, which offered workshops teaching independent-living skills and the arts.

Though sketched in 1978, the messages in “One Struggle” have remained relevant into the 21st century.

As an artist, Tepper was able to contribute numerous skills to Spirit Menders, including the design of many of its newsletters and other printed materials. For this pro-bono work, she often pulled from her vast inventory of drawings sketched since her return from New Mexico. Dozens of these drawings also found their way into Reaching Across: Mental Health Clients Helping Each Other, 1987, a well-read manual for those trying to take control of their own mental health care. One drawing, originally made in 1978, featured a revealing caption below a trio of disjointed, in places incomplete, figures: “If we can make them believe we’re happy, we’re ok,” one of them says of a common and time-honored coping mechanism.

Perhaps because she was accustomed to being a visible and vocal figure in a range of communities, Tepper was not especially secretive about her own tribulations, although there are indications that at times she valued her privacy. For example, in a book titled I’m not crazy, I just lost my glasses: Portraits and Oral Histories of People who have been in and out of Mental Institutions, 1986, Tepper, identified herself as “Clementina Thirty-Seven” and gave this quote to the book’s interviewer: “My diagnosis is adjustment disorder, which means I don’t fit in. For any intelligent human being that’s a sign of a healthy spirit. I resist the insanity we live in.” More publicly, she served on the San Francisco Mental Health Advisory Board from 1986 to 1992.

A button designed for S.F Union of/by the Homeless was reproduced for Tepper’s 2022 exhibition at the Haight Street Art Center.

Tepper’s other primary challenge during these decades was housing. As with mental health, Tepper’s approach to her homelessness led her to advocate on behalf of the S.F Union of/by the Homeless. A button that was designed for the group was reproduced for her 2022 exhibition at the Haight Street Art Center. For the record, Tepper has lived in a single-room occupancy building in San Francisco since the early 2000s; you might say, the issue of housing has been at the forefront of Tepper’s daily experience since her parents left her to fend for herself all those decades ago.

In the end, one would be forgiven if one looked back on the twists and turns of Tepper’s career and then, in an attempt to make sense of it all, proceeded to put Tepper’s output into boxes labeled, say, “Hallelujah The Pill!!” (even more topical, alas, in 2022 than it was in 1967), “Rock Posters,” “Drawings,” “Bread Sculptures,” and the like. Or, at least, I hope that’s true, because that’s pretty much exactly what I did as co-curator of Tepper’s “Laying it on the Line” exhibition. I was not entirely wrong, and I’m extremely proud of that show, but the resulting picture painted of Mari Tepper was incomplete. It captured her work, or what was left of it after the corrosive effects of time, flames, and fire hoses, but not so much the artist or, more importantly, the person, who is as complicated as, well, a Mari Tepper drawing.

Mari Tepper, June 18, 2022.

In retrospect, the biggest missing piece for me was the artist’s relationship with her son. “I don’t really associate with her so much as a mom,” Angus says of his mother. “We’ve had a pretty unconventional relationship. But we really connect. We connected then, and I think we’ve connected later in life as, like, friends and creative people. We can just go down rabbit hole after rabbit hole about color, proportion, whatever. I mean, we geek out. When we’re having a good conversation, she gets me completely. We get each other, our humor, the subtleties of the things we say. We’re on the same page.”

Tepper agrees, and then shares this: “He tells me that because we were close for those first five years, that because he had that maternal love early on, it allowed him to develop in certain ways.”

That’s no doubt a wonderful thing for a mother to hear from a son, but this is a story about Mari Tepper, who would probably wince at any ending that smacked of such rank sentimentality. “He also says he finds my voice soothing,” she adds, “which I think is so funny. I mean, I think I have a pretty scratchy-sounding voice, but I guess it’s okay.”

Hippies, Guns, and LSD: The San Francisco Rock Band That Was Too Wild For the Sixties

Hippies, Guns, and LSD: The San Francisco Rock Band That Was Too Wild For the Sixties

Almost Famous: The Untold Story of an Artist's Rock-Poster Roots

Almost Famous: The Untold Story of an Artist's Rock-Poster Roots Hippies, Guns, and LSD: The San Francisco Rock Band That Was Too Wild For the Sixties

Hippies, Guns, and LSD: The San Francisco Rock Band That Was Too Wild For the Sixties Meet the Swedish Artist Who Hooked British Rock Royalty on Her Revolutionary Crochet

Meet the Swedish Artist Who Hooked British Rock Royalty on Her Revolutionary Crochet Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Leave a Comment or Ask a Question

If you want to identify an item, try posting it in our Show & Tell gallery.