As the metals curator at Colonial Williamsburg in Williamsburg, Virginia, Janine Skerry takes care of one of the top collections of English 18th-century silver in America. In this interview, she discusses Paul Revere and other American Colonial-era silversmiths, early owners such as Henry Wetherburn, and the various processes and technologies used to make silver pliable enough to form objects.

My interest in silver started when I was a child. One of my earliest memories was opening either my mother or father’s jewelry box and using a magnifying glass to look at all the little marks on the pieces inside. There were also a few pieces of metalwork in our family: a copper coffeepot and a small silver saucepan. My great, great, great grandfather in Sweden made the coffeepot, and my grandfather made the little silver saucepan. He passed away when I was 7. It intrigued me that people made metal objects.

This silver and wood teapot from 1759-1760 was made in Edinburgh, Scotland in the shop of Lothian & Robertson. Gift of John H. Hyman: The John A. Hyman Collection.

As an undergraduate, I had the good fortune to take a class on American decorative arts with Charles Montgomery, who was a professor at Yale. It was absolutely fascinating. Yale has a great collection of American silver, and Professor Montgomery was beginning research on a book and an exhibit on American silver going all the way back to the Colonial period.

He was interviewing undergraduate students to participate in this graduate/undergraduate seminar, and I was fortunate enough to be selected. That sealed the deal for me. I ended up doing my undergraduate senior thesis on an English silver collection at Yale, my masters on a silver topic at Winterthur, and my doctoral dissertation on silver at Boston University.

Collectors Weekly: What do you collect?

Skerry: Museum curators have some interesting restrictions on personal collecting. Most museums in America require that their curators either not collect in the same area that the museum collects in, or they require that the curators submit to the museum any objects they’ve acquired for consideration for acquisition.

Basically it means curators can’t compete with their own institutions. I do collect silver, but I’ve never collected materials that are the same culture and period that I curate. Most of my personal collection consists of 19th-century flatware or small objects that fit my budget, but nothing Colonial.

Collectors Weekly: How long have you been at Colonial Williamsburg?

Skerry: From January of 1993 to May of 2009, I was the curator of ceramics and glass. I’d developed an interest in those materials in the mid-’80s and had worked with them for quite a while. So I came to Colonial Williamsburg to work with the ceramics and glass collections. I only became the metals curator in June, 2009.

I had worked as a metals curator in other institutions. When our previous curator retired after 43 years, they held the position open until I had finished a project I was working on and could take over the metals collection. I was familiar with the institution, so they felt I was a good fit for it.

Collectors Weekly: What can people see when they visit Colonial Williamsburg?

Skerry: We have the DeWitt Wallace Decorative Arts Museum and several exhibits that feature silver. There’s the “Treasure Quest” exhibit, which is devoted only to silver. It features the collections of various donors and individuals who’ve been patrons of the museum. We’ve highlighted what their particular interests were. There’s an enormous collection of Sheffield or fused silverplate. There’s an interesting collection of sterling silver made by an English silversmith named Paul Storr. There are some Scottish materials. It’s very thematic. It includes the oldest piece of silver that Colonial Williamsburg received as a gift from our founder, John D. Rockefeller, Jr.

There’s another exhibit called “Revolution in Taste,” which explores the world of goods available to American and English consumers during the Colonial period. It features silver, ceramics, glass, and a whole host of other metals. We have pewter, brass, iron, and a great array of silver. We have things like drinking forms, tankards, two-handle cups and trophies, and a range of personal items.

“The sterling standard was a form of consumer protection.”

At Colonial Williamsburg we have more than 200 period rooms in the Historic Area houses that show objects in the contexts in which they would’ve been used. Peyton Randolph House features a number of objects descended through the Randolph family. Wetherburn’s Tavern shows silver objects that would’ve been used by a very prosperous tavern keeper to furnish dining tables, tea parties, and other social events for genteel society.

We also have Bassett Hall, the home John D. Rockefeller, Jr. and Abby Aldrich Rockefeller lived in while they were here in Williamsburg. It was one of their part-time homes. It’s furnished with the historical collections Mr. and Mrs. Rockefeller personally owned, which includes some 20th-century things. We have their table service of Kings pattern flatware, for example. We don’t have a lot of Victorian material.

Collectors Weekly: What years are considered to be the Colonial period?

Skerry: That’s a little tricky. Although we’re called Colonial Williamsburg, like most museums we have collecting parameters or a collecting mission. We collect from the period of the first British settlement, so from about 1607. People who arrived brought older objects with them, of course. So we do have things that might predate that time period, but we collect from about 1607 all the way up to 1830. Our collections really span the period that would be called Early American, but our greatest strength is in the material from the 1700s.

Collectors Weekly: What are some of the most prized pieces in the collection?

Skerry: For a long time, our collecting focused on high-style English silver. We have one of the top collections of English 18th-century silver in America. We have a lot of works by Paul de Lamerie, who was one of the best-known and most revered silversmiths of the 18th century. We have some very high-style pieces that reflect his best work.

The London shop of Ebenezer Coker created this silver salver, or tray, between 1759 and 1760. The crest is that of the Carter family of Williamsburg and Nomini Hall, Virginia. Funds donated by Mr. Walter W. Patten, Jr., and The McGraw-Hill Foundation, Inc., toward purchase.

Interestingly enough, our holdings in American silver are much more modest for the Colonial period. That’s an area I’m working on now. It’s challenging in the early 21st century to be building a collection of American 18th-century silver, but we’re making good progress. We also have a remarkable collection of English fused silverplate—it’s often called Sheffield plate—thanks to a couple of private donors. It’s one of the largest holdings of that in the country, if not the world.

Like most museums, we happily accept gifts if they fit our collecting parameters. Victorian silver isn’t something we actively acquire because it doesn’t fall within our collecting parameters. Similarly, if someone were to contact me and say, “We have a great collection of Peruvian silver that we formed in the 1960s,” we couldn’t accept it, even as a gift. We purchase things through auctions, from antiques dealers, and occasionally from private individuals.

We recently acquired a wonderful 18th-century American tankard made in Massachusetts but owned for all of its history in Virginia because the family had both Boston and Virginia connections. It descended in private ownership until 2008. At that time we were approached about whether we might want to acquire it and were able to purchase it as a partial gift.

Collectors Weekly: Was the tankard in the family all that time?

Skerry: Yes. A tremendous amount of American silver is still privately owned. A couple of interesting objects just sold at auction in January in New York—one from the 1600s and one from probably just about 1700. They had descended in private families and had been in a continuous line of private ownership all the way up to this point and had never been published, studied, or known by collectors or curators.

When I was in graduate school in the early 1980s, I remember hearing people say: “The Colonial period, it’s all been done. We know everything. Why would you work on Paul Revere? Everybody knows everything about him, and all the great objects are already in collections.” But that’s not true. There are still fabulous pieces in private hands, and oftentimes in the ownership of the descendants of the original owners. Sometimes people notice and treasure them, and sometimes they don’t have a clue.

Collectors Weekly: When did the English start making silver?

Skerry: Silver is one of the oldest products. The term sterling came into use in England in the 1300s as the legally mandated standard of purity for silver. Silver is a naturally occurring element. In its absolutely pure state, it’s too soft to work. If you made a teaspoon out of pure silver, it would become bent and worn just from use. To make the silver stronger, copper is typically alloyed or added to the mixture. You can add other metals as well, but copper is the most common and useful mixture in the alloy.

Because copper can be added without changing the appearance of silver, the sterling standard was a form of consumer protection. Since the 1300s, the sterling standard has meant that the object is composed of 92.5 percent pure silver mixed with 7.5 percent copper. If it doesn’t meet that standard, it can’t be marked sterling. England has had a hallmarking system since the 1300s to guarantee that consumers get what they’re paying for.

Silver was being worked with during the time of Christ and even earlier. Sterling is now widely accepted. It became the legally mandated American standard in the 19th century.

Spoons are the earliest form of sterling flatware, followed by knives. You rarely find knives made entirely of silver. Sterling silver is too soft to hold a cutting edge, so the blades were made of steel. Forks are still later in date. There’s no one specific starting point.

When I was curator of ceramics, people often wanted to know when teacups got handles. I think it would torture and frustrate them when I’d say there was no specific date. Handles were an option that was available by the mid-18th century, and they became increasingly more typical as you got into the 19th century.

People always want to know when the fork was invented, but, again, there’s no single date and time. Forks for cooking, which are usually made out of base metals like iron, precede forks for eating. Sterling or silver forks for eating became increasingly more common at the end of the 17th century and into the 18th century.

Collectors Weekly: Why was silver used for dining?

Skerry: It’s partly that beautiful color and luster. Silver is part of that little group of metals on the periodic table of elements that are considered the noble metals. Gold, silver, and platinum are listed in that category because they’re naturally brilliant and lustrous. They have great color and shine, and yet they’re relatively non-reactive. They don’t tarnish, stain, or corrode easily. That makes them very desirable. Also silver was used as a monetary basis for thousands of years, so it had that intrinsic sense of value.

It’s like diamonds: Why is a diamond valuable? Well, it’s pretty, but what can you do beyond that? From a technological standpoint, diamonds are very useful, as is silver. It’s a great conductor of electricity, but historically, it was simply its rarity and beauty that made it desirable.

Silver is also wonderfully recyclable. You can create a beautiful piece of furniture out of the finest mahogany, but if the fashions change or you move and the scale of the piece is no longer right for your home, you don’t usually have a great deal of success when you start trying to cut up that piece of mahogany and make it into something else. Silver, on the other hand, is infinitely usable. It can be melted down and remade into other objects.

Take a silver teaspoon: you can’t be certain whether the silver in it was mined 10 years ago or 200 years ago and then recycled. The origin of the piece is always a mystery. It’s not only the individual object; it’s the material itself. It can be remade again and again. It raises all sorts of intriguing questions about its history.

These days there are a lot of newspaper ads for companies that buy gold. Gold prices are really high, so jewelers and other firms are advertising, “Bring in your gold, and we’ll pay cash for it.” The ads even say they’ll take broken pieces. That’s because they’re melting it down, refining it, and making it into new objects. It’s the same with silver.

Collectors Weekly: So a piece of sterling silver or flatware could’ve been something else at one point?

Skerry: Theoretically. Dimes no longer have any silver in them, but when I was a child, there were still dimes made entirely of silver. I love the idea that you can hold one of those dimes in your hand and never be sure if it was made from silver mined during the time of Cortez. Was it something that was being shipped on the Spanish Armada? Are there molecules in that dime that were part of a coin that was in circulation during the time of Christ? Silver just has that amazing permanence and durability to it, even as it changes form.

Collectors Weekly: What are some of the earliest pieces of sterling silver flatware in the collection?

Skerry: We have some spoons and some suckett forks that date to the early 1600s. During the period that Colonial Williamsburg represents, when people started to acquire silver, the first objects they’d acquire were spoons. Oftentimes they were either quite large—almost the size of a modern tablespoon—or as small as modern demitasse spoon. Spoons are the entry-level way into owning silver. Once you’ve acquired a certain number of spoons, you might acquire a little two-handle drinking cup, maybe a tankard or a mug. Then you might get a cream pot or a teapot.

By the end of 18th century, the idea of owning a whole set of matching silver flatware had become much more commonplace. The earliest pieces we have in our collection are from around the first quarter of the 17th century.

Collectors Weekly: Do we know the names of the silversmiths from that era?

Skerry: Sometimes. Those early pieces are usually English. When the English government mandated sterling as a legal standard, they instituted several requirements. Over the years, the requirements increased and were strengthened.

By the 1600s, ideally a silversmith would mark some sort of insignia or device, usually with his initials, on the object to indicate that he was guaranteeing the quality of the metal. Then he would take it to a guildhall in London or another large municipal area in England where it would be assayed or tested to make sure it met the sterling standard. At that point, it would be struck with marks that indicated the sterling standard, which city was doing the hallmarking, and the date letter for that year.

A typical piece of English silver from the 1600s or 1700s will include at least four hallmarks or four marks: the maker’s mark, the city mark, the standard mark that indicates purity, and the date letter. That was all designed as consumer protection. It kept the assay officer in charge of testing silver objects from running any scams.

The whole hallmarking system was geared towards preventing fraud. There were enough records to determine if someone was trying to pass off silver that wasn’t up to standard. You could tell by the marks on the object, and you could go back and pursue that person legally. It was a very sophisticated system of checks and balances. In order to make it work, you had to have a record stating who the assay officer was and who the silversmith was that used that particular touch mark. The records are remarkably intact, but the further back you go in time, the less definitive they are.

Collectors Weekly: Was English sterling silver primarily used in America in the early Colonial period?

Skerry: Yes, although American silversmiths were working by the mid-1600s. The first two were John Hull and Robert Sanderson, who worked together in Boston. Hull was born in 1624 and Sanderson was born circa 1608. The earliest Sanderson pieces come from the 1630s, and then pieces from their partnership come later. The English wanted the American colonies to provide them with raw materials and to purchase finished English goods. So most of what we find in Colonial America is English-made silver, but in urban areas like Boston, New York, and Philadelphia, you find that Colonial silversmiths were also present.

The silversmiths were doing two things: repairing silver—polishing and taking out dents, replacing handles, engraving family monograms and coats of arms—and making things. The source of raw material for them was old objects. If a cup was dented or had a broken stem, you might have taken it to Hull and Sanderson so they could remake it for you.

Boston’s most famous patriot and silversmith, Paul Revere, made this sugar urn in about 1795. The piece was retailed by William Holmes, Jr. and is engraved with the initials “JW.”

Hull and Sanderson both used silversmith touch marks. John Hull’s mark consisted of his initials, IH. “I” was used instead of a “J” at that point in time, so “I” was for his first name John and H for his last name, Hull. He used three different marks, all with the letters IH in variously shaped cartouches.

Robert Sanderson also used a mark composed of his initials. He used several different marks, and they all include a rose or sun-like device. John Hull became the master of the first mint for the Massachusetts Bay Colony, so he also made coinage, which wasn’t legal tender in the eyes of the English crown.

Hull and Sanderson were the major makers in Massachusetts. The way the craft was taught was that young men, boys really, were taken on as apprentices. Traditionally, it’s said that the apprenticeship system meant that you started as an apprentice when you were about 14 years old, and you served for seven years. In England, apprenticeships were very regulated, very codified.

In America, there were no guildhalls. There was no hallmarking system where you took the piece to have it tested to confirm it was silver or sterling because we weren’t supposed to be making silver. We were supposed to be buying it. In theory, if we found silver here, we were to dig it up, send it over England, and they’d make it into teaspoons and sell it back to us. In fact, the practice was quite different.

Hull and Sanderson are considered the fathers of American silversmithing because they trained all of these young apprentices in their shop, many of whom went on to establish their own practices. In due time other silversmiths immigrated to America. Both Hull and Sanderson had trained in England before they came to America. The same thing happened in New York, Philadelphia, and Baltimore. You began to get skilled silversmiths arriving, who in turn trained people to work with them.

Collectors Weekly: Who were the prominent English makers?

Skerry: Well, if there’s a Holy Trinity of silversmiths for both England and America it includes three men named Paul. Paul de Lamerie was a French Protestant silversmith who fled during the persecution of the Huguenots from France to England, where the aristocracy patronized him. Paul Revere was taught the trade by his father, Apollos Rivoire, a Huguenot-born silversmith who fled from persecution to the Channel Islands between England and France before coming to America.

Paul Revere’s silver today is considered the pinnacle of American craftsmanship. He wasn’t the only silversmith—some people would argue he wasn’t even necessarily the best—but he is certainly the most famous. He was very prolific, successful, creative, and inventive. He deserves his place in the Holy Trinity.

The third was Paul Storr, an English silversmith who worked at the end of the 18th century. He was responsible for a very bold sculptural style. He ran a huge workshop that eventually became the primary silver producer for the British crown. There are a lot of great silversmiths, but the most widely recognized are the three Pauls.

Collectors Weekly: Who followed them in the Colonial period?

Skerry: In Boston you had the Burts and Hurds. There were at least four craftsmen named Burt: John, Samuel, William, and Benjamin. In the Hurd family there was Jacob, Nathaniel, and Benjamin. These were all outstanding craftsmen. In New York, you had a very strong Dutch influence with Peter Van Dyck and Cornelius Kierstead. As time went on, you began to get silversmiths like Myer Myers, who’s probably the best-known New York silversmith.

Made in the London shop of Daniel Cary between 1634 and 1637, this “slip-end” spoon was found in an old house foundation near Jamestown, Virginia. Gift of Dr. W. A. R. Goodwin.

In Philadelphia there was Philip Syng, who was followed by Joseph Richardson and his sons Joseph and Nathaniel. There are often little dynasties of silversmithing families. When you move down into Baltimore, you also have a large number of silversmiths. Baltimore’s glory days were toward the end of the 18th century and into the 19th century, with the Warner family, for example. Andrew Warner was producing on a very large scale.

I’m not exaggerating when I say there were hundreds of Colonial silversmiths. One of the biggest challenges for anyone interested in studying Colonial period silver is that there’s no one reference book. You really need to pick a focus to get started and then gradually broaden your reading.

For example, Patricia Kane, the curator of the Garvan collection at Yale University, wrote a book called “Colonial Massachusetts: Silversmiths and Jewelers: A Biographical Dictionary Based on the Notes of Francis Hill Bigelow and John Marshall Phillips.” It’s a typical decorative arts book size—11 1/2 inches by 8 inches. It has 1,241 numbered pages, and it’s almost 3 inches thick. It’s enormous, and it’s only on Massachusetts’ silversmiths and jewelers who were already working and producing objects prior to the American Revolution. American silver is a huge topic, and when you go into the 19th century, it gets even more complex.

Sadly, not a lot of silver is being made in America today. In my lifetime, all the major silver manufacturers have undergone dramatic changes and have shifted far from sterling silver production. When I first started in this field, you had Kirk-Stieff in Baltimore; Gorham in Providence, Rhode Island; International Silver Company in Meriden, Connecticut; Towle in Newburyport, Massachusetts; and Lunt in Greenfield, Massachusetts. They were all still in business and producing both flatware and hollowware, tea sets and bowls, and things like that.

There are few manufacturers left today because of changes in social norms and genteel dining practices.

I went on a tour of International Silver in the 1970s. They still had a full-fledged factory and were still producing, but they don’t exist anymore. I don’t think Gorham makes silver anymore. They mostly make stainless and a little silver plate.

Collectors Weekly: Has this change affected the number of sterling silver collectors?

Skerry: No. Most people who collect silver just love the material, the subject, and the history. A teaspoon made two years ago has collector value in the estate or second-hand market, but not in the antiques market. Silver still has value. The value has gone up and down wildly. I remember in the late 1970s and ’80s, a couple of speculators drove the silver market to unprecedented heights. The value of silver got up to around $100 per ounce. I think it might have even exceeded $100 an ounce.

That was a very significant point in silver history because the social customs had changed enough that a lot of younger couples getting married weren’t interested in having silver. It made silver so expensive that very few people could afford it. At that time, a great number of objects were being sold for melt value.

I haven’t checked the papers in the past couple of days to see what silver values are like as a commodity in the market. I think we’re somewhere around $18 per ounce. So it’s dropped dramatically from what it was in the ’80s, but at the same time, it’s never going to be negligible.

Collectors Weekly: So when you say American Colonial silver, that includes the English silver, correct?

Skerry: Not quite. Colonial Williamsburg is a rather unusual institution because we interpret American history as well as American art. Imported objects are part of American history, so we’re unusual in our interest in English silver. But when I talk about Colonial American silver, I really mean American-made. That said, during the Colonial period, most of the silver that was owned here in the 13 original colonies was English. Even Paul Revere imported ready-made silver from England to supplement what he made, sold, and repaired in his shop.

Collectors Weekly: Who were the prominent makers of the silver that was imported to Colonial America?

Skerry: In England the trade was so specialized that you had makers who simply made particular things. In the mid-18th century, a man named Samuel Wood made silver cruet stands day after day. A silver cruet stand is a silver frame or stand that has little compartments that hold glass decanters or glass casters and cruets—they look like salt and pepper shakers—and little glass bottles. The salt is actually served in tiny, round open dishes, but the things that look like salt-and-pepper shakers would hold pepper, dry mustard, sugar, and powdered sugar. Then you’d also have little glass bottles with metal lids that would hold oil and vinegar.

Cruet frames such as this Samuel Wood example, made in London between 1739 and 1740, were very popular in the 18th century. Gift of John V. Rowan, Jr. in memory of Bernard Claude Michael Shrubsole.

Cruet sets were used in the seasoning of food. For example, you could make wet mustard by taking a little oil and vinegar and putting those on the edge of your plate and then mixing in a bit of powdered mustard. You could make it as hot as you liked. Cruet frames were very popular. We find a lot of evidence of them.

Silver epergnes were big, elaborate centerpieces, usually heavily pierced with funky little twisting arms reaching out into space. They held little baskets and dishes for things like nuts or sweetmeats. In the center, you might have fruit. An English silversmith named Thomas Pitts is especially well-known for making epergnes in London during the mid-18th century.

John Carter and Ebenezer Coker aren’t like the three Pauls—they’re not really sought after as great masters whose work is prized and collected—but they’re the type of silversmiths whose work was very common in the Colonies. They clearly made a lot of things for export to America.

We have on loan four salvers made by them in the 1760s and ’70s. A farmer plowed the pieces up in 1961. After finding a silver mug, he got some friends together to look for more. Using a metal detector, they found the four salvers, two mugs, and part of a cruet frame buried between slate roofing tiles about 20 inches below ground. All of them date between 1765 and 1772. It’s likely these pieces were buried to keep them from being stolen.

Collectors Weekly: How many pieces of sterling silver did a typical service contain during the Colonial period?

Skerry: There were no rules. Today, we’re used to the idea that with flatware. Like with dishes, you can buy a service for four, six, eight, or 12. That standardized idea of what constitutes a set didn’t come along until the late 19th century.

Weight was more important. For example, the Randolphs were a very prominent Virginia family. John Randolph was one of the few American colonists to be knighted by the English crown, and Peyton Randolph might’ve been the first president of the country if he hadn’t died at the First Continental Congress—he died during the meeting in 1775.

When his estate was inventoried, it was recorded that he owned 492 ounces of silver. Silver was so intrinsically valuable that in inventories it was common to list the item—be it a teaspoon, coffeepot, or tankard—with the amount of silver it had in it.

For comparison, Randolph’s 492 ounces of silver is equal to about 492 Gorham Chantilly teaspoons. That’s a lot of metal. Randolph also owned more than 250 pieces of china as well as fine glass. He owned a lot of stuff.

I mentioned Henry Wetherburn earlier as someone who owned an amazing amount of silver. We exhibit silver at Wetherburn’s Tavern because there was so much there. He had a silver teakettle on a stand. It’s a large teapot with a spirit lamp underneath it. His probate inventory records that it weighed 130 3/4 ounces. We don’t even own an example that heavy today. He also owned a 25 1/2 ounce teapot. His milk pot was almost 12 ounces. He had another teapot that was 16 1/4 ounces and a coffeepot that was 32 ounces.

Wetherburn had salvers, salt dishes, candlesticks, a quart can. There’s a big tear in the entry of his inventory, so the next few entries aren’t legible. But he also has 16 tablespoons, 11 dessert spoons, 19 teaspoons, and sugar tongs. He had a butter boat—or gravy boat—a pepper box, a punch strainer, two punch ladles, a silver saucepan, 10 silver-handled knives, 11 forks with a case, and one silver-hilted sword. Some of these items might have been American-made, but most would’ve been imported.

Collectors Weekly: Did the wealthy have pieces custom made?

Skerry: The wealthiest patrons in the Southern colonies tended to have factors or personal shoppers back in England because they had an agent to whom they shipped their crops. In return they got letters or bills of credit. The agent would purchase things on their behalf. We often come across records that will say, “I will have a silver teapot in the latest style,” or “I will have a silver teapot, let it be neat and plain.” They’d often ask to have their monogram or cipher engraved on it.

As you go farther north where it’s more urbanized—Boston and New York—there were people who were buying silver from England, but you also had a lot of wealthy Bostonians buying directly from Paul Revere because they felt they could get a better deal than buying from England. For example, a British military commander stationed in Boston during the colonial period purchased a large bowl made by a Boston silversmith and took it back to England. It turned up on the market for the first time about 20 years ago.

It begs the question: Why would someone who lived in England buy silver in America, especially a military commander? What was he doing? The answer is he was getting a good buy. Silversmiths in the Colonies didn’t have the hallmarking system, the market wasn’t as regulated, and there wasn’t as much competition, which means you could really strike a deal compared to London prices.

Collectors Weekly: How many pieces of silver did the typical family own?

Skerry: Owning any silver indicated that you were living above a subsistence level. For purposes of broad generalization, when we talk about households in the 18th century, we tend to think of them as the lesser sort, the middling sort, and the better sort. Those are period terms, not my words. If you were poor, you don’t own any silver. If you were middling, you might own a couple of pieces of flatware or maybe even a single little mug, a bowl, a drinking vessel, or a cream pot—something like that. If you were rich, you had a lot of silver, and you flaunted it.

Collectors Weekly: In England, was silver also only owned by the wealthy?

Skerry: Yes. Silver was only for the middle class and above. I think most historians would argue that in the middle of the 18th century, there were much greater opportunities for economic advancement in America than in England. There was much more social and economic mobility.

Collectors Weekly: Was Colonial sterling silver made by hand or manufactured?

Skerry: It was made by hand, but using all the technological advances available at any point. There was something called a flatting mill, which allowed you to take that rough cast ingot of sterling silver and reduce it into thin, pliable sheet metal from which you could form objects. Flatting mills first came into use on softer metals like tin and lead. They were used by the 12th century for making sheet lead for roofing.

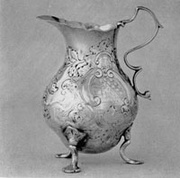

Boston silversmith Rufus Greene produced this handsome tankard around 1740. Partial gift of Courtney Bowdoin Elliott in memory of her father, John Page Elliott; balance funded by the Friends of Colonial Williamsburg Collections.

In his notebooks, Leonardo da Vinci has examples of flatting mills he designed for the Vatican. At that time, the Vatican was minting its own gold coinage. The coinage needed to be exactly the same thickness and weight because the value of the coin equaled the value of the metal. We used to do that, too—a penny is no longer made out of solid copper, but it used to represent one-cent’s worth of copper.

Flatting mills for silversmithing were first coming into use at the end of the 1600s in England. A flatting mill looks a bit like a modern pasta machine with the two rollers. You feed the pasta dough between the rollers, and it comes out thinner, and then you repeat. It was the same idea with silver.

One of the earliest references to a flatting mill in America is from a Philadelphia silversmith named Cesar Ghiselin in the 1730s. Flatting mills still would’ve been very expensive and scarce in England at that point. Without one, the way you made silver flat was by taking the ingot and hammering it, reheating it, and hammering it some more. You could spend a whole day hammering an ingot of silver to get flat metal to work with. Paul Revere didn’t acquire a flatting mill until after the end of the American Revolution. In the 1780s, he paid a man named Solomon Munro to set one up for him.

So silver was made by hand, but silversmiths used as much mechanized technology as was available. By the 19th century, you’re definitely looking at mechanization. After 1860, silver making is centered in areas that have access to waterpower. By the middle of the 19th century, factories were using all sorts of waterpower-driven technologies, like stamping, spinning, and drop pressing.

Collectors Weekly: How many different patterns existed during the Colonial period?

Skerry: There’s really no answer. There are probably half a dozen patterns—such as cannon, trifid, spatulate—that were common; there were no copyrights on those early patterns. Later on, the number of variations increased. Much simpler patterns emerged by the Federal period, along with elaborate engraving. You also begin to see stamped decoration. Hundreds of patterns were being produced in the Victorian Era.

Collectors Weekly: Did the makers invent the patterns?

Skerry: Not really. The vast majority of makers were using common styles. Pretty much everybody used them. Paul de Lamerie developed his own patterns, but they were extremely expensive and for an aristocratic, courtly clientele. There’s no evidence of Paul de Lamerie silver having been in Colonial America.

Collectors Weekly: Were there common motifs in the patterns or styles?

Skerry: Yes, foliage and cartouches, for example. There’s a fairly widespread vocabulary of ornament for any given style. In the Rococo period, you’ve got more relief chasing or cast work. It tends to have a lot of asymmetrical foliage, asymmetrical cartouches. In the Federal period, you go to a very flat, austere surface, but it’s enlivened with beautiful engraving, usually in patterns of little bowknots, ovals, and medallions.

The styles were more or less ubiquitous, but the expressions of the styles were regional. You can look at a Boston tankard, a New York tankard, and a Philadelphia tankard produced at the same point in time and they’ll have regional characteristics. That’s less true with flatware.

A lot of people would argue that American Colonial silver is essentially provincial English silver, but you have definite Dutch and Germanic influences in New York and Pennsylvania. You see more British influence in Massachusetts and the Southern colonies. You can also find French influence in some instances in New York, and later on in New Orleans. English styles dominated, but other nationalities were represented.

Collectors Weekly: How should a collector clean or preserve their sterling silver collection?

Another Boston silversmith, Daniel Parker, made this silver-and-wood-handled teapot in about 1760. Acquisition funded by Friends of Colonial Williamsburg Collections.

Skerry: As gently as possible, and as little as possible. There’s a tendency to over-clean things. In the museum world, curators don’t clean objects, conservators do. I don’t clean any of the metals that I’m responsible for. Our conservators don’t use commercially available polishes because most are too abrasive. That’s a real conundrum because most private individuals don’t have the means to hire a conservator when they need their silver polished.

If you own 20th-century sterling-silver flatware, the best way to keep it looking good is to use it every day and wash it by hand. Don’t put it in the dishwasher. Don’t use scrubbing pads or anything like that. Just wash it, rub it with a soft cloth to get a nice surface, and dry it carefully.

Collectors Weekly: Is it common for collectors to use the silver in their collection?

Skerry: Some people use their silver and some don’t. I’m always the advocate for the object. When people ask if it’s dangerous (health-wise) to use an antique object, my response is usually, “I’m not worried about you, but I’m sure worried about the antique!” Ultimately it’s a personal decision.

Collectors Weekly: Do you have any advice for would-be silver collectors?

Skerry: One of my favorite go-to resources is “The Book of Old Silver: English, American, and Foreign.” It was written by Seymour B. Wyler and published in 1937. I think it’s still in print. It’s certainly not the most current scholarship, but it has some interesting essays that offer a good introduction.

It also has photographs, but most importantly it has a good range of marks from many different countries. In fact, it’s a great reference for London hallmarks, especially for the dates and how to read the date letters. Wyler’s book is not the final resource for makers’ marks, but for figuring out, say, the date letter for 1751, this is an easy book to use and to learn from. It has the major British silver areas, a lot of Sheffield plate, and a great selection of American Colonial silversmith marks.

As for advice, you’ve probably heard this from everyone you’ve ever interviewed, but the most important rule is to collect what you love and love what you collect. No one should ever collect because they think it’s going to be a good investment. We only own these things during our lifetime. We’re temporary custodians. We have to do a good job so that they can be passed on to the next pair of hands.

(All photographs courtesy of the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation)

Paul Revere, His Craftsmanship and Time

Paul Revere, His Craftsmanship and Time

Saving Vermont History, One Silver Spoon At a Time

Saving Vermont History, One Silver Spoon At a Time Paul Revere, His Craftsmanship and Time

Paul Revere, His Craftsmanship and Time The Kalo Shop, a Mecca for Arts and Crafts Sterling Silver

The Kalo Shop, a Mecca for Arts and Crafts Sterling Silver SilverHolding a piece of sterling silver flatware in the palm of the hand is like…

SilverHolding a piece of sterling silver flatware in the palm of the hand is like… Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

A great article- very informative and a wonderfull insight into how curators view what they do. It is fantastic in that an article such as this makes silver live. It will inspire more people to collect and appreciate the historic aspects of what they own or can aquire.

Jeremy Astfalck

Silver Dealer based in South Africa

I was just wondering if you could give me some information on a pair of silver candlesticks. They were purchased in the United States in 1943 from the English Silver Department of Brock and Company Jewelers in Los Angeles (or Beverly Hills), California. The tag is marked with the following:

Article – Pair Silver Candlesticks

Date – George III, Year 1768

Location – London, England

Maker – John Carter

Elegant Specimens

I would appreciate any information that you could offer. Thank you!

It sounds like your candlesticks were made by one of the well-known special silversmiths working in England in the 18th century. John Carter II did not register a maker’s mark with the London guildhall until 1776, but there is evidence that he was making candlesticks for the firm of Parker and Wakelin as early as 1769. It is clear from surviving examples that Carter specialized in candlesticks and salvers or small, footed trays. Your sticks should have 4 marks on them: a leopard’s head crowned (the mark for London); a lion passant (to indicate sterling standard), the maker’s mark “IC” (“I” was used in place of the letter “J” until almost the end of the 18th century); and a date letter. If your candlesticks are from 1769, the date letter should be either a gothic “m” or a gothic “o”. Date letters changed in March of each year, so the “m” is for 1768/1769 and the “o” is for 1769/1770. You can find more information about John Carter II, as well as examples of the marks I’ve described, by searching for “John Carter silversmith” and “English silver hallmarks” on the web. Good luck!

The article was fascinating and I enjoyed reading it. I searched out the article because my daughter is a senior history major at UC Berkeley and would like to be a curator. She is looking into graduate schools but isn’t really sure where to go or what to do other than apply. She spent a semester in residence at William and Mary and took the field study course this summer in architrcture history with Dr. Lonsburry. Is there any chance you could direct me to a few resources to help her figure out how to navigate the future? Thanking you in advance. Kathi Krolop

I was recently at Williamsburg in the silversmith’s shop and was given information on how silver objects were created. I can’t remember what the silversmith called the abrasive which was used to polish the silver to a lustrous finish. Could you help me out?

I have a Theodore Starr (NY) sterling tea service circa 1917 with a suspended tea pot over a warmer. I remember my grandmother using it with this flame warmer under the tea pot. The wick is white clean so I assume that alcohol was the fuel in the warmer. Can you tell me if this was denatured alcohol or what can I use that will not discolor or damage the silver?

Many thanks!

I have two coin silver teaspoons that appear to have Cornelius Kierstede’s “CK” in a square touchmark as well as a square with 12 in it. They have monograms on the back and another monogram on the front of the handle with the date 1869. Could all of this be possible and they were regifted in 1869? Does that drive down the value or are they prized because of Kierstede? Thanks for any help you can supply.

An interview with silver curator and collector janine skerry.. Bang-up :)

I have a silver butter dish made by Meriden B. Company. I’m trying to figure out some information on it. Maybe some history, the time era, and value of my piece. The number on the bottom is 200L. I have tried everything! Please help me out!!

I am trying to determine what silver dinnerware cost in the mid 1700s. I am thinking of a setting for eight people (large plate, small plate, bowl, silverware, plus 2 candelabra), created by a master (i.e. Revere) stamped with an ornate, custom designed monogram. Not the value of the pieces, but what the couple would have paid for them in 1745.

The pieces are fictional, but I would like to be in the right ballpark.

This is an excellent interview and should remain usefully informative for many years.

Personally I collect mainly Victorian American silver. Also Norwegian silver and a little English silver from the same period. It’s a fascinating period and incredibly diverse, with some of the best quality ever. A lot more ornate than Colonial silver (which I also greatly admire), and in general more affordable.

I have a silver bread platter dated 1847 and signed rogers, I an trying to find history and value of this piece.

Fabulous article. Were there any colonial women silversmiths?

How did people of the 1700’s polish their silver? Would men have polished silver shoe buckles? How much would shoe buckles be worth in terms of a day’s wage?