When Steven Spielberg comes calling, you know you’ve done a robot rebellion right. That’s been the pre-publication experience of Daniel H. Wilson, a Ph.D. in robotics whose upcoming novel, “Robopocalypse,” was recently snatched up by the director as the next big androids-destroying-humans epic. Wilson’s most recent novel, “A Boy and His Bot,” is a work of children’s fiction. To learn more about Wilson, visit his blog.

As a kid, I played with lots of robot toys, like Gobots and Transformers. Of course, robots are up there in the pantheon of pop culture icons, along with cowboys, astronauts, and dinosaurs. After I finished an undergraduate degree in computer science, I was trying to decide what to study in grad school, because I knew I didn’t want to get a job programming.

Looking around, I saw robotics on the list of possible research areas. I couldn’t believe that robotics was a real area of study, and that it was on a list of things you could learn. It just captured my imagination. I felt lucky to live in a time when that’s possible—when you can actually study robots.

That’s how I ended up at the Robotics Institute at Carnegie Mellon. For the record, most colleges aren’t as brave as Carnegie Mellon in terms of having a “robotics institute.” Most places still call it “electrical engineering.”

But Carnegie Mellon is very forward-thinking. They’ve been on the forefront of robotics and artificial intelligence since its inception, and they’re brave about acknowledging it as a scientific field. When you’re a dorky kid looking at a list of things to study, that’s pretty appealing.

Collectors Weekly: You published your first book when you were still getting your doctorate. What happened next?

Wilson: Since then I have become a full-time writer. I never really foresaw that. I was going on job interviews while “Robot Uprising” came out. It’s an interesting career twist because robots exist in two places. On one hand, they’re fantastic, and they cause people’s imaginations to run wild. On the other hand, they’re also real, and you can have a real career in robotics. The thing is, there’s not a hard boundary between those two worlds. Most roboticists are inspired by robot fiction. And people that are writing robot fiction are often checking in with a roboticist to see what’s wild and what’s actually likely to happen.

For me, I would really have loved to straddle those two areas in my career as well, but what happened was “Robot Uprising” did well. Then, the movie rights were sold and I realized that writing was a viable career, where I could make as much money as I would as a roboticist.

After that, I started writing articles about robotics for “Popular Mechanics.” That was nice because I got to use my connections in the industry and academia to write about this stuff from an insider’s perspective. But then the pop culture side of robotics and technology started to outweigh the real side of it for me. I began to write more non-fiction books, like “Where’s My Jetpack?” where I got to explore all the retro-futuristic pop-culture icons from the 1950s and ’60s.

Collectors Weekly: Do you think the Internet and modern technology have killed our fascination with robots?

Wilson: I can see that point. A lot of times when you see the reality of a robot, you see it in the lab or you see a video of it, and you think to yourself, “Oh, yes, it’s real. But it’s boring.” That’s because real robots have to compete with a lot of great, exciting fiction. But every now and then, a new advance comes out of a laboratory somewhere, and it blows your mind and just leaves you totally gobsmacked.

For instance, think about the video of the Big Dog robot from Foster Miller. It’s a quadruped walking vehicle designed to follow soldiers through rough terrain, carrying their backpacks. It moves like an animal.

In this video, when they show a person kicking the machine, it reacts by catching its balance. The way it moves, it looks exactly like a newborn horse, and you feel empathy for it. It’s really weird—because it moves like an animal, it triggers something in your brain that makes you go, “Oh, don’t hurt that poor … wait, it’s a robot!” Big Dog doesn’t even have a head, but when you see the movement, it causes this natural reaction.

My mom would go to garage sales and buy like a pillowcase full of G.I. Joes.

For the same reason that we see faces in clouds and tortillas and stuff like that, we just naturally ascribe “aliveness” to whatever objects we’re interacting with. If an object even exhibits the least bit of humanness, then we automatically anthropomorphize whatever we interact with. And it makes sense. It’s what we’re designed to do, really. A lot of what’s going on in our brains is working hard to make faces out of the shapes that are in our environment and figuring out the emotions of these shapes, also called other people.

Robotics provides a unique viewpoint because, as a roboticist, you have to step out of your own self as a human being and look at people as if they’re engineering problems. How do you tell if someone is smiling, or if they want to kill you? That’s a really hard question. It’s easy to do, most toddlers can do it, but it’s actually really hard to replicate. Your job is to break down the problem from an outsider’s perspective and figure out how to solve it.

Collectors Weekly: What about little robots that come together to form a bigger one?

Wilson: It sounds like you’re describing modular robots. If you take this idea to its logical conclusion, then each of the units becomes the size of a grain of sand, and you have something like the liquid metal T-1000 Terminator robots from “Terminator 2.” The modules are a lot bigger than that right now, but that’s the scale they’re headed toward. Modular robots are very handy because they can shapeshift to solve a variety of problems. That’s especially useful if you’re someplace where you can’t just get another part or tool—like deep space.

If you think about it, every robot is really a solution to a specific problem. Animals are similar in this respect. Every successful animal has evolved to fill whatever niche it has in the ecosystem. Robots are the same way. The difference is that sometimes robots, including modular robots, will take very nontraditional approaches to solving the problem. That can be pretty scary when you see robots breaking in half and then recombining, or flooding across the floor like a liquid.

Collectors Weekly: Historically, how have we viewed robots in the U.S.?

Wilson: In the United States, people have traditionally been scared of robots. It makes sense when you consider how robots were initially portrayed here. Early on, like the ’50s or earlier, there was no difference between a robot and a vampire or a werewolf—they were all made up. Aliens, alien monsters, robot monsters—they were all the same, just totally made up, with no basis in reality, figments of your imagination. Nightmares.

The Unimate was a robot arm that weighed 4,000 pounds. It was added to the General Motors assembly line in 1961.

When we reached a point where robots start becoming real, it was as if someone had discovered a real werewolf. It’s going to take a little while before people get over their long-ingrained fear. What if there really was a werewolf, and he was a nice guy? Well, it would still take a little while for people to get over it and to come to accept it. In popular culture, there had been this long-standing animus built up toward robots from the way they had been portrayed as aliens and just bad guys.

When real robots started showing up in the ’50s—there was Unimate, the first robot arm—companies were afraid to use them because they were afraid of the harm it would do to their public image. So, for instance, General Motors agreed to use the first robot arm ever invented by an American, but only in secret. They only agreed to use it in one warehouse so that they could determine whether it worked without letting everybody in America know that they had found a werewolf and were using it to build cars.

No such animus existed in Japan, and they very quickly adopted robotic arms, unlike in the United States. And their car industries completely overtook United States car manufacturers over the following decades. Now, though, robots are constantly in car commercials; they’re synonymous with technology and progress instead of just villains. Robots are making a transition from being nightmares to being something real and, as a result, something much more complex than just a bad guy with wavy arms carrying off a space princess.

Collectors Weekly: How did the ’50s idea of a robot servant come about?

Wilson: From the U.S. perspective, technology ended World War II and saved a lot of lives, and everybody got to come home from the war. So people were wearing rose-colored spectacles in relation to technology. My favorite thing about that era is that people really thought that technology was going to solve every single problem. They thought, “We’re no longer going to eat food that comes from a tree. We’re going to eat food pills!”

Basically, everything was up for improvement. By the 1960s, with “The Jetsons,” the future was a utopia where the robots do all your housework for you, and everybody loves it. People loved the robot, Rosie, the maid, even though there are definitely real-world issues related to employing robotics. Today, there are modern-day Luddites who believe we shouldn’t explore new technology, but I think that the Neo-Luddites are in for a long haul because human beings pretty much just create technology. If a cheetah runs fast, humans think fast. It’s ingrained in us. There’s no stopping this train we’re on.

Today we’ve come full circle. Now, everyone says, “Gee, Mother Nature knows best. We need to get back to the basics and eat organic food grown locally.” It’s like, yes, well, what do you think human beings have been doing for the vast majority of pre-history and history? So, yes, it’s interesting how feelings can completely reverse when it comes to technology.

Collectors Weekly: When processed food was first created, it was a lot more sanitary that the bulk stuff sold in barrels. Now, no one wants it.

Wilson: Well, that’s the thing about technology—there are always unintended consequences, sometimes good and sometimes bad. Robots embody that because they are the ultimate technology that you create and then let go, and it does whatever it’s going to do after that. You’re hoping it’s good, but it could easily go wrong, as an autonomous tool. Of course, there’s always the basic fear that we’re going to replace ourselves because robots really impinge on our territories as intelligent creatures. We’re the smartest animals alive, and that’s why we’ve conquered the planet. And so we’re creating something that plays with us in our own field.

Recently, IBM’s Watson supercomputer handily beat two Jeopardy! champions.

For instance, IBM has created this machine called Watson that can play Jeopardy! It can actually answer in English. It speaks. It can interpret the question. It can hear the question and see it written, interpret what it is, look it up, and then answer in the form of a question. I saw in an article where it smoked two of the best Jeopardy! players in the history of the game.

That’s getting into our territory, and that can be threatening. Human beings only have one trick and that is to outsmart each other, the environment, and other animals. If we create something that can do our one trick better than we can, that’s threatening.

Collectors Weekly: Could robots be programmed to have free will?

Wilson: Well, computers can already make those sorts of decisions, and it’s not even that hard to program. The idea of free will is not something we’ve got domain over. With a computer, with any sort of artificial intelligence, you use machine learning to solve a certain sort of problem.

The human-rights movement on the horizon is whether people who have technology in their bodies will still be considered people.

Typically, you build a robot with AI to solve a problem that you’re not going to be there to solve yourself. It’s going to be on its own and you can’t tell it what to do ahead of time. It has to learn. So it has to go into the environment and look and see, for example, what type of bomb it is, and then look to see where the wires are, and then figure out how to snip the wires. You can’t tell it what to do in every possible situation.

You can teach it some stuff, but then it’s going to have to generalize, just like a person does. It’s going to have to learn new information and then make up its mind. There is no way a human being can fully predict what the machine is going to do and what decision it’s going to make. That’s about as close to free will as human beings get, and if it’s good enough for us, then it’s good enough for robots.

Collectors Weekly: So that’s the scary part?

Wilson: Well, it can be scary, mostly because you’re afraid your robot’s going to fail. And things can get complicated. There are a lot of fascinating ethical implications. My last book, “A Boy and His Bot,” a middle reader for ages 9 to 12, just came out in January. In the story, a 12-year-old boy goes into basically an experimental world that was created a long time ago by an ancient civilization and has been abandoned for thousands of years. It’s a place where robots have been evolving on their own with no oversight—they don’t even know what a human being is. Going into this world is really fun because evolution can go so many different ways.

For instance, in this world, there is a robot that was designed to make happy faces and copies of itself, and it nearly destroyed the entire world by painting every available surface with happy faces and copying itself. Actually, in this world, there was a big war to stop the spread of these happy faces. There’s an area called the Topiarian Wilds where gardening robots have essentially been sculpting these woods for thousands of years to the point now where every blade of grass is meticulously crafted to form amazing, mind-blowing mazes and patterns, a topiary maelstrom.

There’s another robot called the Infinipedek—once they started building it, they never stopped. He’s always being built, so he can never stop moving. He’s just always got to go. It’s fun to explore all these sort of logical absurdities in a fantastic way because it’s a kid’s book, and you can go to the edge of your imagination.

Collectors Weekly: Do you think robots are still a fantasy realm for kids?

Wilson: Yes, but I think that if a kid reads “A Boy and His Bot,” they’ll come out on the other end with a better understanding of robots because I’m not writing just completely fantastic, silly robots that have no basis in reality. That’s tempting, but I think that’s the easy way out.

For instance, I have the kid, Code, traveling with this robot named Gary, who’s an atomic slaughterbot. He’s a great, big robot. At various points, Gary is kind of mystified by Code and his human properties. For instance, when Code goes to sleep, Gary assumes that Code has died because he can’t believe that human beings actually just go unconscious and limp for like eight hours a day. That is inconceivable to him as a robot.

When Code says, “There’s danger ahead,” Gary takes it very literally and is scanning the road ahead for danger. And then Code says, “I mean in time,” so Gary tries to figure out why Code would use this metaphor. He looks at Code and says, “I see. All your sensors, your eyes and your nose and your ears, all that stuff is pointed frontwards. So you automatically think you’re coming through time and that it’s ahead of you. I get it.” And Code is like, “You don’t feel that way?” And Gary says, “Oh, no. My sensors point in every direction. I get information from satellites. I can see any direction I want.” It’s these differences that come from robots not being embodied in the same way that humans are that makes you think. I had fun with that.

Collectors Weekly: What is “Robopocalypse” about?

Wilson: Exactly what it sounds like. Robots attack all the people. “Robopocalypse” has got the full weight of my robotics background in it, but I tried to keep a pretty traditional, easy-to-convey theme at the heart of it. One thing that’s tiring about science-fiction books is that you have to learn this whole world and it takes forever to figure out what the deal is. They’ve got different words for everything, and it’s hard to relate to it quickly.

For the same reason we see faces in clouds, we just naturally ascribe ‘aliveness’ to objects we’re interacting with.

With “Robopocalypse,” I intentionally went with something that you can convey easily. It’s a robot uprising in which technology turns on humankind and tries to kill us. From there, I tried to introduce complex themes and be thoughtful and punch the reader in the gut with the actual story and my characters.

The idea of robots attacking people is a meme, and that’s why it’s easy for people to understand it in one sentence. That’s an advantage and a disadvantage. The advantage is that you hit the ground running. The disadvantage is that it could be stale because so many other people have already done it. But I was very careful to make sure that the world was consistent and that everything made sense. It’s about the characters and their relationships. I’ve read a lot of sci-fi books with robots in them, and I’m proud of my book. I hope that other people agree with me that it’s not a stale approach.

Collectors Weekly: Obviously, it got Steven Spielberg’s attention.

Wilson: Well, he’s really into robots. What’s surprising is that my name wasn’t even on any of the stuff he read. He didn’t know about my background; he just read leaked pages and then eventually tracked me down. It’s a little bit surreal.

Collectors Weekly: Have you had other books optioned?

Wilson: Yes. I’m no stranger to that. My first book, “Robot Uprising,” was also optioned. Anytime you write a book, you create this intellectual property for which you can sell the publishing rights, but you also have these dramatic rights. So it pays, literally, to remember that when you’re writing or when you’re coming up with the big concept.

Wilson’s first book, “How To Survive a Robot Uprising,” and its sequel may soon be a film starring Jack Black.

“Robot Uprising” and the sequel “How to Build a Robot Army” are both currently under option at Paramount. When that option expired, and I just gave it to Steve Pink and Jack Black, which is really exciting. Those guys are really funny and smart. They’re working up a pitch right now to studios based on making it a Jack Black movie. Steve Pink directed “Hot Tub Time Machine” recently, but he also co-wrote “Grosse Pointe Blank,” one of my favorite movies ever, and “High Fidelity.” I mean, come on, that’s an iconic movie.

These guys are really talented, and they were waiting in the wings to get this. They were just waiting on Paramount to let it go, which really cracks me up. And then “Bro-Jitsu,” my only sort of non-technology book, was optioned by Nickelodeon, and I wrote the screenplay for it. That option has also expired. And then “Robopocalpyse,” of course.

The novel that I’m writing right now, “AMP,” was just optioned by Summit, with Alex Proyas attached. He’s an amazing director with all kinds of street cred. He did “The Crow,” “Dark City,” “I, Robot,” and recently a movie called “Knowing.” Summit is the company that produced “Twilight,” so they’ve had good luck with book adaptations, and are riding high off that.

Collectors Weekly: I’ve read that the book you’re writing right now is about people with disabilities who gain superpowers, yes?

Oscar Pistorius has been called the fastest man on no legs.

Wilson: The superpower angle has been overhyped. It’s basically about the human-rights movement of the current generation. We’ve already seen, in past generations, more rights movements than you’d really ever expect. When our country was founded, it was “all men are created equal” and “men” meant only white men who owned land.

Since that time, we’ve seen rights movements based on race, religion, gender, sexuality, age, disability status, all these things. I think the human-rights movement that’s on a near-term horizon is whether people who incorporate technology in their bodies are still people. That’s really what “AMP” is about.

It’s not about superheroes or robots. It’s about a little kid who’s diagnosed with ADHD and comes back to school with an implant—the teacher refuses to teach that kid. What happens then? So it’s very personal and real. Again, the technology is based on my best research and the best that I can do in terms of predicting what I think might really happen and how it would affect people.

Collectors Weekly: Does “AMP” relate to the story of Oscar Pistorius, the South African sprinter who was born without legs below the knee?

Wilson: Well, it’s all wrapped up in our concept of what’s considered “cheating.” Oscar Pistorius is a fascinating figure when it comes to this movement. Right now he runs slower than the fastest human sprinter, but he’s evolving a lot faster than human beings are because he’s got technology attached to his feet. The technology gets better faster than human conditioning can, so he or someone like him is going to run faster than a natural human and become the fastest thing on two legs. Then everybody in the world is suddenly going to have to deal with the fact that the disabled person is the fastest and the strongest. I’m sure it’s just going to proliferate from there. There’s going to be a huge shift in attitude.

Collectors Weekly: Who are your influences among science fiction writers?

Wilson: What I thrived on growing up were science-fiction short stories because they were like “Twilight Zone” episodes. They usually had one great concept that was explored. Like, okay, this is a world where people can teleport. This is a world where you can travel faster than light. Then, there’s a wicked twist at the end. Each one of these stories is like a well-constructed, little machine that gives you a jab.

The Wilson reading list includes short stories by Arthur C. Clarke, Philip K. Dick, and Roger Zelazny.

My favorite three short stories ever have got to be “Second Variety” by Philip K. Dick, which is a “Terminator” precursor; and then “For a Breath I Tarry” by Roger Zelazny, which just makes you want to cry; and then “Nine Billion Names of God” by Arthur C. Clarke. Damn, that’s a good one. It just gets you.

I loved reading those because you just get to jump into all these different realities. Very quickly you have this mental puzzle where you can explore how this world has been affected by whatever fictional piece of science it contains. As I got older, I started appreciating characters more and books about people that were not just focused on the sci-fi aspects.

Collectors Weekly: Do you collect things lots of robot stuff?

Wilson: When you do anything long enough, people just give you stuff related to it. So I have a lot of robots around the house. I have lots of robot toys and lamps, and a robot clock in my daughter’s room. This year, I gave all the robots I got for Christmas from various people to my daughter, which was nice because she’s new. I’ve actually got a robot that I bought from a thrift store on my first date with my wife. He’s really cool looking, but I don’t know anything about him from a collectibles standpoint except that it says No. 902 on the back, so I just call him 902. He shows up in a lot of stuff I write, actually. So I have an impromptu collection of robots. It really wasn’t my decision to collect but it happened anyway.

Robots are up there in the pantheon of pop culture icons, along with cowboys, astronauts, and dinosaurs.

I’ve got a few of tin toy robots, but none worth any money. The oldest things I collect are old “Popular Mechanics.” I got quite a few from the early ’50s. They crack me up because the guy I got them from, when he read these things in the ’50s, he would circle the inventions that he thought were going to be a big deal. Now it’s been 60 years, and you go through it and read something like, “This is a lawnmower that you can sit on top of like a tractor. We call it a ‘riding lawnmower.'” He’s got it all circled up, like, “That’s a good one. Riding lawnmower—that’s going to get big.” It’s pretty fun.

Collectors Weekly: When you were a kid, did you collect comics? Clearly you had Transformers.

Wilson: Yes, and “Mad” magazines, man, tons of them, and G.I. Joes. I was really into G.I. Joes. I don’t really know if I ever even got any new G.I. Joes that came from a store. My mom would go to garage sales of parents with older kids and she would just buy like a pillowcase full of G.I. Joes and throw it in a box, and that would be Christmas. I loved it because it was just a load of G.I. Joes.

I would enact huge battle scenes—the G.I. Joes were my little actors. Honestly, now that I’ve started writing novels, I don’t think what I do today is much different from what I was doing as a kid in the backyard. I would set up a little encampment, and then I’d have one guy show up and these other guys would be having a conversation around the campfire. I was really just setting themes, acting them out, and writing the dialogue. I’m basically doing the same thing now.

(Photo sources: Unimate, G. I. Joe, Optimus Prime, Rosie, Watson)

How Science Made Your Dino Toys Extinct

How Science Made Your Dino Toys Extinct

Attack of the Vintage Toy Robots! Justin Pinchot on Japan’s Coolest Postwar Export

Attack of the Vintage Toy Robots! Justin Pinchot on Japan’s Coolest Postwar Export How Science Made Your Dino Toys Extinct

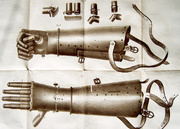

How Science Made Your Dino Toys Extinct War and Prosthetics: How Veterans Fought for the Perfect Artificial Limb

War and Prosthetics: How Veterans Fought for the Perfect Artificial Limb Science Fiction BooksFor book collectors, vintage science-fiction titles hold a special appeal. …

Science Fiction BooksFor book collectors, vintage science-fiction titles hold a special appeal. … RobotsThe 1950s was a particularly good decade to be a toy robot. The world was g…

RobotsThe 1950s was a particularly good decade to be a toy robot. The world was g… Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

”Growing up in the 1970’s,there wasn’t alot of g.i.joes to enjoy.” ..BUT..as one got older ,in the 1980’s,watching commercial jingles ,about g.i.joe comic books,action figures, and vehicles …especially..The 1986 COBRA NIGHT RAVEN S3P BLACK JET TRANSPORT PLANE”. Yes ,those were good years”.