What would jazz look like if it had a physical presence? According to Sherry Ann Byrd, a celebrated quilt maker who posts on Show & Tell, it might look something like the hand-made “M-provisational” quilts produced by six generations of her family, who descended from a former slave named Edward “Ned” Titus in Freestone County, Texas.

Her family’s creations—like the improvisational quilts of so many families of former African American slaves across the U.S.—are explosions of fabric and colors with sometimes hard-to-discern patterns and a logic all their own. The improvisation is visible in each quilt, as mismatched swatches seem to flow together into one pleasing whole. Some have clear patterns, but with uneven lines and unexpected changes in color or order. Byrd shares her personal connection to these creations on her blog, Quilt Stories by Sherry Ann.

“In our family, we have a great love of music and quilt-making. We love to dance, sing, and make music,” says Byrd, who is a cousin to the late jazz musician Kenny Dorham. “I’ve always been surrounded by music and quilts. To me, they are alike. Both are improvisational, and they just move people. Instead of playing jazz with musical instruments, we play jazz with a needle and thread.”

Of course, some of Byrd’s most prolific quilting kin, who have been celebrated in museum exhibitions all over the county, have also sewn precise, traditional American quilt patterns with equal aplomb. But the improvisational quilts are the most captivating, as they seem to have the heart and life story of the maker stitched right into them. Last month, Byrd’s mother, Laverne Brackens, was named a 2011 Heritage Fellow by the National Endowment for the Arts for her quilts.

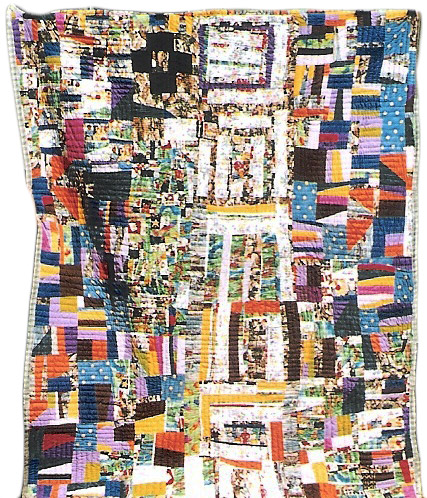

This riff on the checkerboard quilt pattern was pieced by Rosie Lee Tompkins of Richmond, California, and quilted by Willia Ette Graham of Oakland in 1986. Part of Eli Leon’s collection, from the exhibition catalog for “Who’d A Thought It: Improvisation in African-American Quiltmaking,” San Francisco Craft and Folk Art Museum.

At first glance, African American improvisational quilts resemble the crazy-quilt fad of the late-Victorian period, but that’s a superficial connection at best. Improvisational quilts are actually constructed in an entirely different manner. Many of them, at least in the Titus family lineage, are made using the string method.

“What they do in my family is take newspaper and cut it up into blocks,” Byrd explains. “Often, after you make a regular quilt, you have a lot of little pieces left over. Some of it is real stringy; some of it is little small triangles or odd shapes. The quilters will take those pieces, and they’ll sew them onto the piece of newspaper to make a quilt block. When they have about 30 blocks, they’ll sew them into a quilt top.”

However, unlike traditional quilts, it’s often not obvious where the blocks are, and Byrd adds, “It can trick the eye.”

Quilt titled “Who’d a Thought It,” pieced by Francis Sheppard of Las Vegas and restructured and quilted by Irene Bankhead of Oakland in 1987. Part of Leon’s collection shown in the exhibition of the same name.

Quilt collector Eli Leon, who passed away in March 2018, explained that while improvisational quilts may look spontaneous, they do require technical proficiency and quilting know-how. “Improvisational quilts are not crazy at all,” he said. “They often have a number of patterns in one quilt. They may even be the same pattern on the whole quilt, but it doesn’t necessarily look that way because the pattern keeps varying.”

Like most folk art, until about 25 years ago, improvisational quilts were dismissed as shoddy, artless work of unskilled craftspeople. Even Byrd and her family saw them as utilitarian objects, which could be sewn quickly out of scraps and used to keep multiple children warm in uninsulated houses.

Then, in the late 1980s, one of Byrd’s quilts was showcased in an exhibition at the San Francisco Craft and Folk Art Museum, called “Who’d a Thought It: Improvisation in African-American Quiltmaking.” The exhibition highlighted the breath-taking work of a dozen underappreciated improvisational quilting talents, such as the late Rosie Lee Tompkins, whose quilts soon took the art world by storm.

“String,” pieced by Rosie Lee Tompkins and restructured and quilted by Willia Ette Graham in 1985. From Leon’s collection in the “Who’d a Thought It” catalog.

Leon—an Oakland, California, resident who amassed many collections in his lifetime, including toasters, 1930s salt-and-pepper shakers, and quilts of many kinds—first came across improvisational quilts and the work of Sherry Byrd in the early ’80s. He knew he’d unearthed a unique form of folk art, and one that deserved a spotlight.

“I was going around to museums and showing them slides of mine, wanting to do a show,” Leon said. “The curators I met were very doubtful that I had anything of interest. They didn’t like the improvisational quilts and certainly didn’t think that they were as special as I did. But the director of the San Francisco Craft and Folk Art Museum at the time, J. Weldon Smith, was a scholar of African art. He was fascinated and allowed me to have a show.”

Despite all the curatorial doubts, the show was a runaway hit, as museum-goers immediately responded to the quilts’ life-affirming vibrancy and brilliance. “I wasn’t going to have a show without a catalog, so Smith agreed to do a catalog,” Leon said. “He ended up printing 10,000 of them, and they all sold out.”

A 1940s improvisational quilt by an unknown maker in Johnson County, Indiana. Part of Leon’s collection featured in the “Who’d a Thought It” catalog.

In fact, the exhibition was such a hit, it toured the country, stopping at around 25 different museums, including prestigious institutions such as the Smithsonian. The show put the San Francisco museum, now called the Museum of Craft and Folk Art, on the map.

Since the popularity of improvisational quilts exploded, numerous legends about their role in the lives of slaves came to light. One popular story was that when a particular sort of log-cabin pattern quilt was hung outside, it indicated a safe house on the Underground Railroad. Another claims that improvisational quilts had escape routes mapped out on them, either in topography or star patterns. Leon, who’d become a scholar of these quilts, said both stories seem unrealistic to him, but that doesn’t mean quilts weren’t used by the Underground Railroad in some way.

Leon saw a similarity between improvisational quilts—which he calls antithetical to traditional American quilting—and textiles produced in West Africa and the Congo. He cited commonalities such as broken patterns, improvisation, and palindromic motifs, as well as a great variety of bordering styles.

“Compound Strip,” by Cora Lee Hall Brown of Mount Enterprise, Texas, in 1981. Part of Leon’s collection in the “Who’d a Thought It” catalog.

“In standard traditional quilts, you have the same border going around all four sides.” Leon explained. “In African textiles, that almost never happens. More often African textiles have only a border on one side, one or two pairs of borders, or non-similar borders on three or four sides, and that is true for improvisational African American quilts as well.”

As Leon, a white man, continued to publish books and showcase his collection around the country over the next 20 years, his race never seemed to be an issue. Byrd and her family, for example, were pleased find such an an enthusiastic buyer and advocate.

However, racial and class tensions came to the surface after another community descended from former slaves emerged as a center of improvisational quilting genius: The tiny town of Gee’s Bend in Wilcox County, Alabama, which was an important part of the Freedom Quilting Bee in the 1960s. The quilts started garnering local attention in the ’80s. A 2002 show called “The Quilts of Gee’s Bend” at the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston, Texas, though, is what brought the women international acclaim, as well as controversy.

For six years, these buzzed-about Gee’s Bend improvisational quilts toured the country, landing at the prestigious Whitney Museum of Art in New York City, the Smithsonian, and the Philadelphia Museum of Art. In 2006, the U.S. Postal Service issued a sheet of 10 commemorative stamps featuring images of the Gee’s Bend quilts.

This quilt was designed by Arlonzia Pettway in 1982. It’s based on the “housetop” pattern and can be found in “Gee’s Bend: The Women and Their Quilts,” Tinwood Books, 2002.

As these improvisational quilts from the an impoverished town in the South became more and more coveted by wealthy urban elite, questions began to arise about whether whites—collectors, buyers, dealers, and other business people—were exploiting and making a profit off an art that originated from slaves. In 2007, two of the Gee’s Bend quilters, Loretta Pettway and Annie Mae Young, sued white collector and dealer Bill Arnett and his family over copyright and proceeds, accusing the Arnetts of “gross exploitation.” Eventually, the suit was dismissed by U.S. District Judge Callie Granade of Mobile, Alabama.

“You can’t be uptight when you’re making improvisational quilts.”

No such animosity plagued the relationship between Leon and Byrd’s family. Leon met Sherry Byrd, who was living in Richmond, California, at the time, through an ad he placed seeking quilts in a San Francisco Bay Area weekly. “Now, I didn’t know that he was specifically looking for quilts that were made by African Americans,” she explains. “He came out to my apartment to look at my quilts, and right away he wanted to buy almost everything that I had. This just knocked me off my feet!”

At that point, Leon’s quest had just started. Some time before he met Byrd, he was introduced to an unusual double-wedding-ring pattern at the Oakland home of an African American woman selling her family’s quilts. He became absolutely fascinated.

“An ordinary double wedding ring has to be very exact or everything gets out of place, and yet, this one had everything out of place, but it was beautiful,” he explained. “I was flabbergasted. Shortly thereafter, an African American carpenter became very interested in my quilts. He called to say that his brother had died and his five sisters were all in town from all over the country—these were people in their 60s—and he wondered if he could bring them by to see some quilts.

A traditional American double-wedding-ring quilt, from Wichita, Kansas, from 1935, compared with Eli Leon’s first improvisational quilt, a variation on the double-wedding ring pattern, by Emma Hall of Sweet Home, Arkansas, circa 1948. Part of Leon’s collection, seen in the “Who’d a Thought It” catalog.

“When they came over, I asked the women if they were familiar with the double wedding ring, and all but one of them said yes, they were. But since one of them wasn’t sure, I first showed them a Kansas double wedding ring from the ’30s that was very exquisite and a standard traditional, and they loved it. They said, ‘Oh, it’s very delicate,’ and they were whispering and just barely touching it with their fingers and talking to each other about how beautiful it was.

Legend says, when a particular log-cabin quilt was hung outside, it indicated a safe house on the Underground Railroad.

“They liked it so much that I was nervous about their reaction to the improvisational one. But when I brought it out and spread it out, and they started to stomp and scream and carry on like this was the end of the world, it was so fabulous. They loved them both, but their emotional reactions were totally different.”

Looking for the source of the jubilation led to Leon’s decades-long quest to find and document African American improvisational quilts and quilt makers. With an obsessive passion any collector could relate to, he doggedly sought out the creators of the quilts he bought at a flea markets when he suspected they were African American in origin.

When he met Byrd, she had just started quilting herself. In 1984, Byrd lost one of her sons to stillbirth. At the time, she was in her 30s, and living in Richmond with her husband, Curtis. Even though she’d grown up around quilting in Texas, she never had the patience for it. But when her baby died, quilting called to her. She started to make improvisational quilts, and took to it quickly. She’d grown up watching her grandmother piece improvisationally.

The moment Leon saw Byrd’s work, he was so excited, he even wanted to buy her unfinished quilt tops. Byrd then called her mother in Fairfield, Texas, Laverne Brackens, who was in her 70s at the time, and mentioned to her that she met a man interested in buying African American quilts.

“Medallion,” piece by Arbie Williams and restructured and quilted by Willia Ette Graham, both from Oakland, in 1987. Part of Leon’s collection featured in the “Who’d a Thought It” catalog.

Brackens had also rejected quilting as a young woman. Instead of becoming a stay-at-home mom, she entered the workforce, as a cook. As Byrd tells it, her mother was a hard worker, often taking three jobs at once, until a disabling injury in the 1980s forced her to stay off her feet.

“Here she was, at home, unable to do all the stuff that she used to do, and she was mad at herself because she couldn’t do it,” Byrd says. When her daughter called to tell her about the money-making opportunity quilts were providing, Brackens dusted off her sewing machine. “Now that she couldn’t have a regular job, she started making quilt tops.”

It turns out, Brackens had a natural gift for improvisational quilting. Since the ’80s, she’s created more than 300 quilts, stunning in their beauty, and sold most of them to Leon, who even drove out to Texas to meet her and Byrd’s grandmother, Gladys Celia Durham-Henry, as well as dozens of other quiltmakers. That’s how Brackens found herself a lucrative new career in her 60s, a career that’s still going strong 25-some years later.

Why was Leon so interested in the quilts from Byrd, Brackens, Henry, and others descended from the Titus family lineage? He puts it simply: “They’re endlessly talented.”

To learn how to make improvisational quilts, Byrd had called Henry in Texas, and asked her grandmother to send quilt blocks for her to study. “Instead of discarding them when I was finished, I held on to them. Then, I started hearing about other family members that were quilt makers.”

And so, just as the world was on the verge of discovering the beauty of improvisational quilts, Byrd was starting to piece together her family history—quite literally—for a project that turned into a 20-year labor of love.

“In one of those quilter magazines, I had seen a pretty sampler quilt, and so I decided to collect blocks from family members and make a sampler. But as I started to discover more about the history of the family’s quilt makers, it blossomed into something else. It was still a sampler quilt, but now it was turning into a story quilt. As I would get more and more blocks, I would get more and more history.”

A detail of “Jazz With a Needle and Thread” shows the Bible verse, the heart-shaped rug, the tatting, crochet, and beads that pay tribute to Byrd’s grandmother, Gladys Celia Durham-Henry. Photo courtesy of Byrd.

This quilt, which Byrd titled “Jazz With a Needle and Thread,” started in 1984, was featured in the 2006 five-year anniversary exhibition at the Bob Bullock Texas State History Museum in Austin entitled “It (Still) Ain’t Bragging If It’s True.” Byrd’s quilt documented the triumphs of the Titus family alongside exhibits about other great Texans. The accomplished quilt-makers in her family were also celebrated at another MOCFA exhibition, curated by Leon, that same year, “Will the Circle Be Unbroken: Four Generations of African-American Quiltmakers.”

Byrd’s story goes back to Edward “Ned” Titus, and the day he and his large extended family—owned by Simeon and Nancy Lake and brought to Texas from South Carolina in 1852—realized they were freed by the Emancipation Proclamation on June 19, 1865, or “Juneteenth.” On that day, they set about looking for a new place to live and farm. With a little ingenuity, Ned Titus managed to purchase 300 acres of land in Freestone County, which he dubbed “Titus Farm,” quite a feat for a newly freed slave.

On Titus Farm, the women were responsible for the cooking, cleaning, sewing, and child-rearing. The girls learned quilt-making at an early age, as it was as important to the fabric of this family as jazz, blues, and gospel music were. Although, perhaps, none of the women realized at the time how brilliant and unique their hand-sewn creations were.

The front side of “Jazz” is a tribute to Byrd’s late grandmother, featuring her handmade Scotty dog quilt, purse, and tam hat. The reverse (seen at top) features quilt blocks from four generations descended from former slave Edward “Ned” Titus. Photos courtesy of Byrd.

“On ‘Jazz,’ there are four generations that have samples of their work, and then I have history blocks with writing that tells about the earlier two generations of quilt makers,” Byrd explains. “Everything on the side with the big heart on it was created by my grandmother. She was a craftswoman at heart. She did quilts. She did hats. She sewed clothes for herself and her family. She crocheted. She tatted. Just whatever you can name, she did it, and she basically was self-taught.”

The side dedicated to the late Gladys Henry is a visual feast, that includes a a small Scottish terrier-themed quilt that lay on Byrd’s grandfather’s bed for years, a heart-shaped rug, a purse made of plastic and crochet, a crochet tam hat, and even beads woven into the fabric. A Bible verse written on a ribbon is sewn into the piece, and it reads, “Jesus said … Although poor .. This woman out of her want … gave all she had …, Luke 21:1-4”

“I thought that Scripture had perfectly described my grandmother and the women of her generation,” Byrd explains, “because they didn’t have very much, but they were always doing what they could for their family and anybody else in the community.”

On the reverse, Byrd has sewn in quilt pieces made by herself, her grandmother’s sisters, a distant cousin, her mother, her sisters, her sister-in-law, her five daughters, and her son, who was 11 at the time. When she couldn’t find pieces from the older generations, she wrote in parts of the oral family history.

This detail of the front side of “Homegrown” shows some of the doll-like faces Byrd drew and sewed into a salvaged britches quilt. Photo of courtesy Byrd.

While Byrd and her mother were reluctant quilt-makers at first, the older generation, Byrd’s grandmother Gladys Henry and her sister Katie Mae Durham-Tatum and sister-in-law Juanita Louise Henry-Durham, had been making quilts since they were little girls. Katie Mae, who is 94 and was making quilts until last year, couldn’t keep a quilt, they were so pretty and coveted. As soon as she made one, someone wanted to buy it.

Juanita’s husband, Byrd’s great uncle Alonzo, was a hard-working farmer, who would wear out the knees and elbows of his work clothes. Naturally, those old britches became material for an improvisational quilt.

“In our family, instead of playing jazz with instruments, we play with a needle and thread.”

“When they would get to the point where she couldn’t repair them, Juanita would just take the cloth, the good part of the shirts and things, and cut it up into strips. She eventually made one quilt that was nothing but his old farm clothes,” Byrd explains.

Another so-called “britches” quilt, which Byrd found at a Freestone County salvage yard, became the basis for a different family-history story quilt. Byrd took this quilt made of old work pants and drew and sewed doll-like faces into it, and wrote out much of the family story on the reverse. She named this piece “Homegrown,” and finished it before “Jazz,” in time for its showcase at the opening of the Bob Bullock Museum in 2001.

Through it all, Byrd has found inspiration from her grandmother—who was always looking for clever ways of making the best of what she had, including collecting the grandkids’ popsicle sticks to make a flower pot. Her grandmother’s tendency toward generosity, recycling, and giving everything she had infuses Byrd’s quilt-making.

Most of all, like jazz, improvisational quilting is about letting go and seeing where your creativity takes you. “You can’t be uptight when you’re making improvisational quilts,” Byrd says. “You got to just be relaxed, take your time, put the pieces together. If you don’t like them, take them apart and redo them. Don’t be afraid to chop a piece out or add a piece on. That’s what it’s all about. It’s like mixing up a recipe; you just keep at it until you’ve got something beautiful. You can’t be afraid to experiment because that’s what improvisation is all about.”

On the reverse of “Homegrown,” Byrd tells the story of the Titus family lineage. This quilt was featured at the grand opening of the Bob Bullock Texas State History Museum. Photos courtesy of Byrd.

(The late Eli Leon’s collection of nearly 3,000 quilts made by African Americans has been gifted to the UC Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive.)

Black Is Beautiful: Why Black Dolls Matter

Black Is Beautiful: Why Black Dolls Matter

Why Aren't Stories Like '12 Years a Slave' Told at Southern Plantation Museums?

Why Aren't Stories Like '12 Years a Slave' Told at Southern Plantation Museums? Black Is Beautiful: Why Black Dolls Matter

Black Is Beautiful: Why Black Dolls Matter Why the 'Native' Fashion Trend Is Pissing Off Real Native Americans

Why the 'Native' Fashion Trend Is Pissing Off Real Native Americans QuiltsQuiltmaking and patchwork have been popular pastimes in the U.S. since the …

QuiltsQuiltmaking and patchwork have been popular pastimes in the U.S. since the … Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Wonderful article! Makes me want to start quilting.

thankyou-just the connections i needed to make with my own practise-no need to sacrifice an idea for symmetry!

A WONDERFUL ARTICLE ABOUT MY LOVE, QUILTING. IT MAKES ME WANT TO ADD MY TATTING AND CROCHET TO MY QUILTING AND TO MAKE MY CRAZY QUILTING MORE IMPROVISATIONAL, LOVED THE QUILTS.

This is a thoughtful, feeling account of an artistic tradition and the man who studies it. The illustrations are high quality, especially the details. A model for such and article.

love your articles about quilting and your quilts. I too got bitten by that bug and it now my house have them every where. I ‘am the third generation of quilters in my family of Stallings,Samuels and Shannon. Yes I’am the proud owner of my grandmother and my mother quilts. I do need to set down and write the history of each one but that would take my time from handquilting .I hope in the future to post some of them and let you see them.

Beautiful work…..which despite the amazing artistry of the pieceworkers and quilters….. still, almost none of us would have known about without Eli Leon’s practical and scholarly work…..AMAZING ALL THE WAY AROUND…….

Stunning, absolutely amazing – thank you for showing us these wonderful pieces and your article too. Very talented.

I absolutely loved the article I ran across this type of quilting in Lousinanna in a library my daughter bought me the book. I fell in love with quilt making this is my type of art.I had tried to do traditional quilts but it was too uptight and I got so frustrated. When I saw this type of quilting I said this is me. I have done a quilt with traditional and improvisional pieces and plan to do many more. I cant stop. Thank you I loved your article it really incourages me.

Exciting, fun, makes me want to do cartwheels all around my craft/art room! Made a good sized frame coullage of my scraps and framed them on long oblong fra me in my studio, and lo it was enjoyed by friends-and I just did it for fun to draw/create feeling of the top of my desk! Wow, what a day! Your work reminds me of my hanging portrait of my desk treasures scattered all over, like leaves in autumn. Thankyou for sharing! Iam now turning my designs into quilts of love for all my grand children! You are inspiring! Glenda

A wonderful article, and seemingly written by someone who was “into” African-American quilts a long time. Eli Leon was there early, and his exhibition book was very useful to me back when. Despite recent attention, there is still a long way to go appreciating this work, and I will never forget the women I met while picking them up years ago in Mississippi. When I found one, I always paid more than they asked, as few had considered them valuable, even the makers…hopefully those days are over, and with articles like this, I am sure they are. Thanks Lisa.

Jim Linderman

NEED THAT

This is absolutely awesome. I have never seen anything like it.

Jeanetta Mesner

Clovis, New Mexico