Tis the season for buying presents. As you peruse your local mall, you might find yourself drawn to beautiful geometric patterns in vibrant colors, long associated with Navajo rugs, Pendleton “Indian trade” blankets, and Southwest Native American pottery. They’ll be everywhere you look, on sneakers, pricey handbags, home decor, and high-fashion skirts, coats, and jackets.

But many Native Americans are less than thrilled that this so-called “native look” is trendy right now. The company that’s stirred up the most controversy so far is Urban Outfitters, which offered a “Navajo” line this fall (items included the “Navajo Hipster Panty” and “Navajo Print Fabric Wrapped Flask”) before the Navajo Nation sent the company a cease and desist order that forced it to rename its products. Forever 21 and designer Isabel Marant also missed the memo that the tribe has a trademark on its name; thanks to the Federal Indian Arts and Crafts act of 1990, it’s illegal to claim a product is made by a Native American when it is not.

Chief Joseph wears a Pendleton blanket in 1901. He is famous for leading a long-standing resistance to the U.S. government, which had ordered the Nez Perce to move to an Idaho reservation. Photo by Major Lee Morehouse, courtesy of Bob Kapoun, via “Language of the Robe.”

“The problem,” says Jessica R. Metcalfe, a Turtle Mountain Chippewa and doctor of Native American studies who teaches at Arizona State University and blogs about Native American fashion designers at Beyond Buckskin, “is that they’re putting it out there as ‘This is the native,’ or ‘This is native-inspired’. So now you have non-native people representing us in mainstream culture. That, of course, gets tiring, because this has been happening since the good old days of the Hollywood Western in the 1930s and ’40s, where they hired non-native actors and dressed them up essentially in redface.

“The issue now is not only who gets to represent Native Americans,” Metcalfe says, “but also who gets to profit.”

“Our land, our moccasins, our headdresses, and our religions weren’t enough? You gotta go and take Pendleton designs, too?”

Of course, this is not the first time Western fashion has appropriated imagery in the name of aesthetics, as fashion historian Lizzie Bramlett points out in her blog, The Vintage Traveler. For example, the pattern we think of as “paisley”—now most commonly seen on ties—was once a holy symbol of the Zoroastrians in Persia. And throughout fashion history, designers have been swiping motifs from other cultures—from China and Japan in Victorian times, Egypt in the 1920s, and West Africa and Latin America in the ’60s.

But Native Americans have a unique place in the history of the United States. Today, many Native American communities are still reeling from the impact of colonization, which started when white Europeans first invaded their homelands and continued as the colonists established a new order and repeatedly attempted to dismantle the native cultures. That this dismantling should continue at the mall can be especially disheartening.

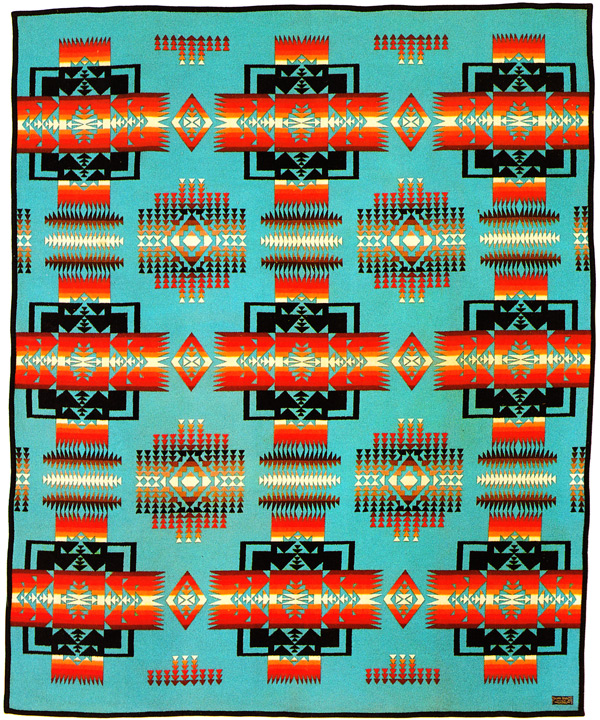

This nine-element robe, named after the esteemed Chief Joseph, was first introduced as an Indian trade blanket by Pendleton in the 1920s. Via “Language of the Robe.”

Even Pendleton, which has fostered warm relationships with various Native American communities since it began producing wool Indian trade blankets more than a century ago, has raised a bit of ire with its new fashion-forward collaborations and collections designed to appeal to a broad, if well-heeled, audience.

Pendleton’s latest foray into young, urban fashion is its fall 2011 Portland Collection, first available in September. For the line, the patterns and fabrics used in the company’s 100-year-old Indian trade blankets were incorporated into high-end cocktail dresses, nerd-chic cardigans, and big blanket-like Tobaggan coats covering the white models like sophisticated Snuggies (models wearing the coats are pictured at top).

This Pendleton travel bag sells for $180 at Urban Outfitters, a clothing retailer that has recently caused controversy with its own “Navajo” line, since renamed.

While these things are trendy and “in the now,” Pendleton blankets have a much more permanent place in Native American culture. In the 1992 book, “Language of the Robe,” Rain Parrish, a Navajo anthropologist, writer, artist, and former curator at Santa Fe’s Wheelwright Museum of the American Indian, explains that her family and friends always come to Navajo ceremonies and dances wrapped in their Pendleton blankets.

“As the light from the fire illuminated the moving bodies and blankets, the swirling shapes, lines, patterns, and colors sprang to life. I no longer saw blankets, but rather the familiar designs of the Holy People coming to life from the sand paintings. I saw moving clouds, glowing sunsets, varicolored streaks of lightning, rainbow goddesses, sacred mountains, horned toads, and images like desert mirages—all dancing before my eyes.

“Colorful blankets are often the chosen gift,” Parrish continues. “We welcome our children with a handmade quilt or a small Pendleton blanket as we wrap them in our prayers. For our young men and women, we celebrate the transformation into adulthood, by discipline, values, acknowledgement, and gifts. As they lie on a thick bed of Pendleton blankets, we massage their bodies for good health. For a couple’s marriage, … the woman’s body is draped with a Pendleton shawl, the man’s with a Pendleton robe. As we move into old age, we pay tribute to the spirit world with ceremony, prayers, and gifts. Often we bury our people with their special possessions and beautiful Pendleton blankets.”

Does that make the hip, couture Portland Collection the same sort of exploitation of Native American culture as the Urban Outfitter “Navajo” line? Here’s where it gets tricky: Pendleton blankets, while marketed to and adopted by tribes across the United States, were not originally designed or manufactured by Native Americans. So to understand the debate about the place of what we assume is Native American iconography in contemporary fashion, you have to look at the history of the Indian trade blanket.

These limited-edition shoes, created by Japanese designer Taka Hayashi for Vans Vault in 2010, incorporate Pendleton wool weaves and now sell for hundreds on eBay.

Deep in the Southwest, as early as 1050, the Pueblo people had developed hand-weaving techniques on vertical looms. But the Spanish conquistadors, who invaded the Pueblos in the 1500s, had made their mark on the native weaving craft by the 1600s, seen in the use of wool and indigo dyes, as well as the simple stripe patterns. By 1650, the Pueblo Indians had taught their trade to the Navajo, who eventually developed their own distinct weaving style. They took inspiration from the land, and created geometric shapes to represent the things they saw, like mountains, clouds, owls, and turtles.

“We know that the blankets, especially the Navajo blankets, were inspired by the world around them,” Metcalfe says, explaining that these blankets had a story. “Sometimes, there were references to the geography, but they were abstracted.”

Four young women wrapped in blankets, circa 1890. From “Language of the Robe,” courtesy of Western History Collections, University of Oklahoma library.

Tribes in the Northeast at the time relied on animal hides to keep warm. That’s why, in the late 1700s, insulating and water-repellent European felted wool blankets became the most coveted barter items for the local tribespeople trading with the Hudson Bay Company in present-day Canada. The most popular of these was Hudson Bay’s off-white, pointed “chief’s blanket,” striped with bands of cobalt, gold, red, and green on either end.

In the late 1880s, when the railroad finally opened the Southwest and the rest of the 1803 Louisiana Purchase to East Coast tourists, white Americans were enchanted with the beautiful geometric patterns used in Navajo blankets. The Victorians would take these blankets back to their overstuffed homes and use them as conversation-piece rugs. Traders, sensing an economic opportunity, encouraged the Navajo to weave these throws with stronger materials and more muted colors suitable for the floor.

Then, in 1895, a woolen mill opened in the Oregon town of Pendleton to sell blankets and robes to nearby Native American tribes. The mill went out of business, but in 1909, brothers Clarence, Roy, and Chauncey Bishop, who came from a family of weavers and entrepreneurs, reopened the facility as Pendleton Woolen Mills.

“The issue now is not only who gets to represent Native Americans, but also who gets to profit.”

Employing the Jacquard loom technology first imported to the U.S. in the 1830s, Pendleton and other new U.S. mills were able to make felted blankets with stunning colors and patterns. Naturally, all the these wool companies looked at the Native American populations, who had at this point adapted wool blankets, often striped or plaid, as a part of their ceremonies and rites of passage, and saw an opportunity.

To Pendleton’s credit, its loom artisan Joe Rawnsley spent a lot of quality time with the local tribes, such as the Nez Perce, to learn what colors and patterns would appeal to them most. As a side note, the Nez Perce most associated with the brand, Chief Joseph, who heroically stood up against the U.S. government for years, had very little involvement with the company. He was photographed by Major Lee Morehouse wearing Pendleton blankets in 1901, but according to Robert J. Christnacht, manager of Pendleton’s home division, that was “the extent of Chief Joseph’s relationship with Pendleton.”

Rawnsley’s early blankets were well-received by the nearby Nez Perce, so the company sent him on a six-month tour of the Southwest, where he lived with Navajo, Zuni, and Hopi to find out what blanket designs those tribes would prefer. He returned with hundreds of ideas. “Baskets, pottery, weavings, and regalia all inspired Joe,” Christnacht says. “Pendleton blanket designs were a blending of the images and colors Joe saw with his own design aesthetic.”

“It’s a crazy cross-cultural mix any way you look at it.”

Some might say that Rawnsley was simply inspired by the beauty of Native American arts and crafts, and he hoped to use his Jacquard skills to make beautiful blankets the tribespeople would love. And in that, he succeeded. Others might argue that this was an early and sly version of cultural thievery. It’s a slippery slope.

“From the beginning Pendleton marketed the blankets to various native communities, but the designs themselves are not authentic,” says Bramlett, a founding member of the Vintage Fashion Guild. “What’s ironic is that the Navajo were making blankets for the white tourist trade, and Pendleton was making blankets to sell to the native communities. That’s kind of a weird twist, but that’s the way it was.

Pendleton banded robe, first featured in the the 1904 catalog and also in the 1910 catalog. Via “Language of the Robe.”

“And the Navajo designs were not even traditional designs,” she continues. “A lot of the motifs that they used were Mexican inspired. Or when traders came to them with oriental rugs, they’d use them as inspiration. So there are oriental motifs in some Navajo weavings, too. It’s just a crazy cross-cultural mix any way you look at it. You’ve got the Pendleton blankets which are a mixture of native and non-native colors and motifs. Then you’ve got the Navajo blankets, which are the same way.”

What we do know is that Pendleton blankets were a hit, and quickly became a staple of life for Native Americans all over the country. They were used at powwows and rites of passage, as treasured gifts, as a means of non-verbal communication.

“Personally, when I think about that history, I think it’s a really cool, the fact that the entire company—and it wasn’t just Pendleton, there were other woolen mills as well—developed because the market for this item was so strong in native communities,” Metcalfe says. “These blankets were integrated right away into our ceremonies. Pendleton also realized that different communities and different tribes had different preferences for designs or colors. And then they created blankets that different communities would like.”

Patricio Calabaza, left, wears a Navajo blanket, and Rafael Lobato, right, wears a Pendleton blanket, at the Santo Domingo Pueblo, circa 1930. Photo by Witter Bynner, courtesy of Museum of New Mexico, via “Language of the Robe.”

At the same time, Pendleton also sold the blankets to white people as exotic items for their homes.

“If you look back at the advertising of the day, it’s vague,” Bramlett says. “They didn’t come right out and say, ‘This is an authentic Navajo design,’ but they could lead you to believe that. They realized there was a market for non-native people to use these in their homes. Heck, they were in business to sell blankets. They didn’t care who bought them.”

All of this to say, it’s very hard to parse out the proper credit for these “native” textile patterns popularized by Pendleton and others—let alone when this appropriation first happened. In the early 20th century, Pendleton blankets seemed perfect complements to the rustic, spare style of the Arts and Crafts movement, and by the early 1910s, Christnacht says the company was expanding these patterns to couch covers, rugs, and robes. Later, they were adopted by cowboys and competitive horse riders as saddle blankets.

“The time when Pendleton came into existence, the 1900s, was the all-time low for native communities,” Metcalfe says. “This is at the height of the reservation era, when we were confined, we were essentially prisoners on these small plots of land. But in that same breath, while our cultures were under threat from this outside force, that’s when we turned internally to protect what we had, and we also get some of the most beautiful beadwork and most beautiful jewelry coming out of that period of great stress.

“Connected with that great assimilation movement was the height of collecting. The late 1800s was when a lot of our stuff left our communities. On the one hand, you have this push for trying to absorb or get rid of ‘The Indian Problem.’ Then, they were taking all of the items that embody that culture, to collect them and put them in museums and claim ownership on them.”

This Tomi Girl dress was made by Lakota designer Mildred High Elk Carpenter, out of a Pendleton blanket, for her MILDJ Native Fashion line. It’s worn by N8tv Dyme’s top model Katrina Drust. Photo by Tiara Carpenter, Native Doll Photography, Bellingham, Wa.

In the 1970s and ’80s, top American designer Ralph Lauren became enamored with Navajo rugs, Plains beadwork, and Apache pottery. He launched his Santa Fe line of clothing featuring concha belts, petticoat skirts, “Indian patterned” sweaters, and blanket jackets in 1981 as another defining aspect of American culture. In the 1990s, the Pendleton and other Native American-inspired designs swelled in popularity again with the return of “Southwest” style and rise of “new country” music.

In recent years, Pendleton has been going to town with collaborations using the iconic Indian trade blanket patterns. It had sold these patterns to Vans, famous for making skateboarder shoes; produced high-fashion lines with Manhattan couture company Opening Ceremony; and it is even offering products through Urban Outfitters. With Levi’s, Pendleton launched a line of jean jackets and cowboy shirts called Navajo Cowboys, hiring Navajo rodeo champions like Monica Yazzie as models.

“The reason why Pendleton was able to maintain themselves—and they’re the only woolen mill that survived—is because of their dedication to the native communities and realizing the native people were their main market,” Metcalfe says. “The blanket for us has become associated with idea of native pride, associated with achievement, community, and community service.

“Now Pendleton’s entering the mainstream fashion scene, doing these collaborations, and it is probably a smart move for them, as a business. But we feel like we have some ownership with this company, and we do question whether they’re stepping away from their relationship with us.”

For some, like Cherokee writer and Ph.D. candidate Adrienne K., who blogs at Native Appropriations, it’s confusing and saddening to see her beloved Pendleton selling stylized products to wealthy young Manhattanites who are as removed from the native way of life as any American could be.

“Seeing hipsters march down the street in Pendleton clothes, seeing these bloggers ooh and ahh over how ‘cute’ these designs are, and seeing non-Native models all wrapped up in Pendleton blankets makes me upset,” she writes. “It’s a complicated feeling, because I feel ownership over these designs as a Native person, but on a rational level I realize that they aren’t necessarily ours to claim. To me, it just feels like one more thing non-Natives can take from us—like our land, our moccasins, our headdresses, our beading, our religions, our names, our cultures weren’t enough? You gotta go and take Pendleton designs, too?”

Monica Yazzie, a 19-year-old Navajo barrel racer from La Plata, New Mexico, models the Levi’s Workwear by Pendleton woolen poncho.

Metcalfe says she’s observed, to her amusement, that the Vans collaboration has been a big hit with Native American communities, but the Opening Ceremony line is dismissed as ridiculous. For Adrienne K., the stratospheric prices of the haute-couture Pendleton items just adds injury to insult.

“There’s the whole economic stratification issue of it,” she writes. “These designs are expensive. The new Portland Collection ranges from $48 for a tie to over $700 for a coat. The Opening Ceremony collection was equally, if not more, costly. It almost feels like rubbing salt in the wound, when poverty is rampant in many Native communities, to say ‘Oh, we designed this collection based on your culture, but you can’t even afford it!’”

This screen grab from the Opening Ceremony web site shows a model in three different Pendleton sweaters, all over $500.

On the other hand, Native American designers, too, like Sho Sho Esquiro, of Kaska Dene and Cree descent, and Mildred High Elk Carpenter, a Minucoujou Lakota living in Montana, have also taken inspiration from the Pendleton blankets, sewing them into to modern fashion items like skirts, jackets, dresses, and even hoodies.

“It’s really cool to see how they reinterpret the blanket,” Metcalfe says. “For Sho Sho, she’s using very vibrant colors and the bold graphics of the Pendleton blanket and giving it this hip-hop vibe, by making these hoodies for men and women. She’s made the wearing blanket something cool for Native Americans to wear again.”

Bramlett says she’s glad Adrienne K. and other bloggers are speaking up, because it’s bringing up all the ways Native Americans have been exploited and misrepresented in mainstream culture. Having grown up in the ’60s, Bramlett remembers a time not so long ago when it was considered acceptable to portray “Indians” as violent enemies in movies, television, and children’s books and cartoons.

Even though the cultural tides are turning, a Cherokee-run company in North Carolina still makes knockoffs of ceremonial Sioux headdresses for children to play “cowboys and Indians” with. And Ke$ha and other young scenesters seem to think there’s nothing wrong with donning copies of sacred headgear for partying at summer rock festivals like Coachella.

“When you see pictures of some of these festivals where young white women are all dressed up in Indian regalia, you wonder, ‘What the heck are they thinking?'” Bramlett says. “What adult is going to do this? Do you not realize you just look dumb?”

The cover of the Pendleton catalog, circa 1901. This 24-page catalog offered blankets and photographs of the Plateau Indians by Major Lee Morehouse. Image via “Language of the Robe.”

And even though she finds fashionistas wearing the high-end clothing made out of Pendleton fabrics much less egregious than concert-goers wearing headdresses, Bramlett says it still can look like children playing dress up. “If it’s something that’s that strong a design that is so strongly associated with one culture, it makes you look like you’re trying to be something you’re not.”

Still, Pendleton, who is also known for folksy Americana plaids (inspired by Scottish tartans) and The Dude’s sweater in “The Big Lebowski,” has to find a way to stay viable in today’s brutal international market, Bramlett says, or it goes out of business—and its beautiful blankets go with it. Christnacht says that 100 percent of the blankets are woven and manufactured in the United States, and half of those, which go for about a couple hundred dollars a piece, are sold to Native Americans. In 2009, Pendleton, which employed about 900 people nationwide, had to lay off 43 workers and consolidate operations in response to slow sales during the recession.

“To stay in business, they have got to appeal to younger consumers,” Bramlett says. “They just have to. And so if they want to collaborate with Levi’s or Vans or whoever else they’ve been in bed with, that’s fine and good. If that industry were to collapse, it would be gone. I’ve seen this a dozen times. Once it’s gone, it’s gone and it’s very soon forgotten.”

A 1910 Pendleton banded robe, also offered in the 1904 catalog as a round corner blanket. Via “Language of the Robe.”

Metcalfe says you’ll never get a consensus from the Native American community on what Pendleton should or shouldn’t do, but ultimately there is a great love of Pendleton, which has often produced blankets to give back to the community, like the one designed by Osage artist Wendy Ponca that benefitted the American Indian College Fund. It’s just—like you do in any long-term relationship—they get a little annoyed with the company sometimes.

“I think ultimately the collaborations are a good thing because they’re opening a door to greater understanding,” Metcalfe says. “Hopefully, those people wearing these clothes will learn a little more about Pendleton’s history and why we have respect for Pendleton. It is because their sense of service to native communities.”

The Beautiful Chaos of Improvisational Quilts

The Beautiful Chaos of Improvisational Quilts

Uncovering Clues in Frida Kahlo's Private Wardrobe

Uncovering Clues in Frida Kahlo's Private Wardrobe The Beautiful Chaos of Improvisational Quilts

The Beautiful Chaos of Improvisational Quilts How Railroad Tourism Created the Craze for Traditional Native American Baskets

How Railroad Tourism Created the Craze for Traditional Native American Baskets BlanketsThe first time any piece of cloth or bedding was called a “blanket” was in …

BlanketsThe first time any piece of cloth or bedding was called a “blanket” was in … Native American Rugs and BlanketsIn many ways, the story of antique Native American rugs (sometimes referred…

Native American Rugs and BlanketsIn many ways, the story of antique Native American rugs (sometimes referred… Womens Clothing“Clothes make the man,” said Mark Twain. “Naked people have little or no in…

Womens Clothing“Clothes make the man,” said Mark Twain. “Naked people have little or no in… Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

An excerpt from Indian Country Diaries on PBS:

Since first contact, Native Americans have been given three choices — which weren’t really choices at all.

Assimilate

The first “choice” was for a tribe to assimilate into the dominant American culture, become “civilized,” give up tribal ways and be absorbed into America society. Many tribes tried this, many times through history. Education was the tool for assimilation in the boarding school experience. The government push to assimilate native tribes continued through the 1950s Urban Relocation Program.

Relocate

Even if a tribe, like the Cherokee, tried to join the American society, they could still be forced to relocate to Oklahoma Indian Territory hundreds of miles away. That’s what happened on the Trail of Tears.

Genocide

Some tribes chose to fight or were forced to resist. While many have won some battles, they lost all the wars. Hundreds and thousands of Native Americans were killed in battles or by disease or starvation. One of the worst examples of genocide was what happened to the California tribes.

http://www.pbs.org/indiancountry/history/assimilation.html

Everyone has a valid argument, regarding the ‘Taking of the Knowledge of Turtle Islanders’. However, I, for one, a number of years ago, was ‘lost and outside the Circle’. My family had removed themselves from any ties with the portion of their lineage referring back to Native Americanism that even to ask about was received negatively, even embarrassingly. For me, attending a christian- orientated church, while growing up, just did not ‘Touch My Spirit’.

It took research, extensive reading and understanding of what I was in need of to fulfill my ’emptiness’. Books, like “Black Elk Speaks”, “John ‘Lame Deer’ Fire” and the Controversial Book, “Honta Yo”. With these ‘sacred, ‘rapings of the Religion’ (but sharing of The Knowledge), writings shared with Outsiders wanting to know more about ‘The Ways’, has helped me (and I expect others, whatever their blood-lines) to ‘find their way back’ to Mother Earth and Father Sky. To embrace the Great Spirit and the Church of The Land (away from concrete, steel, plastic and stain glass structures of the city) has given me a Fullness that was lacking, a Tie with Those that have lived before me and around me, within the Circle. I have been able to embrace That Part of Me that was Taken Away.

Yes, it goes both ways, but ‘helping people to also Understand the symbolism behind the Ideas, Beliefs and Designs’, will help, more than hinder, the Spirit- Sharing between different groups of People… at least Those that Stand with an Open Mind & Heart.

I Pray to the Four Directions All find Peace Within the Circle of Life.

Hechitu-wilo

What an informative post, thanks! Gib Ennis

Wonderful article! We are linking to this great article on our site. Keep up the great writing.

My head is spinning at sooo many comments on this issue. I identify with Native American garb probably because I have ancestry at least on one side. Funny how I always naturally dressed rustic. Whatever’s in our blood will come out. Hey! Maybe we’re all one blood!

When we love others, more than ourselves, the world will live in peace.

First, this is a well written article. Thank you for that. And I offer my sincere apologies to any Native Americans who might feel offended at what I am about to say. It is absolutely not my intention. I am, though, one of those white women that one of the other posters was dissing. However, years ago, when I was going through a very ugly time in my life, I was introduced to Native American culture and philosophy by some Native American friends who were reaching out to offer me some hope and healing by showing me a different way, a better way, to understand life. I listened and studied and asked questions and read–and I loved. My friends breathed new life into my soul with what felt like a new perspective that made sense to me, one that I continue to cherish and embrace. It was life saving and life changing. I didn’t pursue Native American philosophies in some New Age attempt to be cool or to”get in touch with myself.” Native American philosophies found me, and those beliefs are profoundly sacred. They taught me how to stop being so self centered and to learn to embrace all of creation with a much deeper respect. I realize there will be some who believe that I don’t deserve to celebrate Native culture because my skin is the wrong color. I can’t change the skin I was born into. However, do I have some things in my home that were made by Native Americans that I bought from them? Yes. Do I, once in awhile, wear Native symbols or designs? Yes. Is it done in a flippant, boastful way or to make a fashion statement or with any intent or spirit of exploitation? No. Not ever. Those symbols now are sacred to me too because of the sacred lessons I learned from people that I love, and every one of those symbols around me points me towards the better person I am now, and the much better person I still strive to become. Those symbols are reminders that are calming and grounding and center me away from those parts of my own culture that, frankly, I reject and detest. I have a deep love and gratitude for those lessons my friends shared from deep within their spirits. And while I cannot speak for everyone who wears a Native design, I can only speak for myself. I am thoroughly appalled and my heart aches when I see someone wearing regalia to propel their own fame or their own bank accounts. So, to anyone who might get offended if I wear my tiny medicine wheel necklace, I merely ask you to reconsider that while I might be white, we are not all the same. It doesn’t mean I can’t have some limited understanding of your culture, and it certainly doesn’t mean that I don’t value it or love what I do understand of it.

What’s next? Non natives will be wearing feathers and later claim it’s bad luck. Urban outfitters are lame and Natives should become more aggressively competitive with the authentic products. Our native designers need to be cutting edge with our own ready to wear fashion apparel. The East Asians have their kurti and tunics, you can’t buy them in stores, you have to make them if you want them badly enough.

I know some people have aggressive views on this so if you want to argue don’t bother reading my comment. I understand a lot of non natives aren’t even aware that the trend is offensive. But personally I think that if you really care about the culture you should spend time learning about the history or actually talking to someone who is part of the culture, rather than trying to buy it. It’s ridiculously shallow. Navajo’s put an enormous amount of time and effort into weaving. It’s something most white teenagers today honestly would never be able to do. Weaving is deeply rooted in Navajo culture and it tells their story in the context of poverty and war. Most of the culture has been robbed of them so this is something people need to learn to respect. Dressing native isn’t a style, it’s a political statement. Most people will claim that they are Native Indian because they want to feel entitled to the land or so they aren’t dealing with white guilt. When my grandmother was young she said that if you were Indian you would hide it at all costs. The fact that this trend is so popular just shows the hypocrisy of white politics. If you have to buy “native style” clothing to build up your ego then go to a real Navajo and learn the history rather than buying from a store that’s consistently appropriating their culture into a disposable trend for hipsters.

I’m native American and I’m not offended at all more of these things should be made more and in japan

I am American Indian and Caucasian and proud of it. I do not like the term Native American. To me, Native American means anybody who is and was born in America is a Native American.

It does not offend me if a “white person” wants to dress up and portray being an American Indian or a “white person” wearing American Indian jewelry. I do understand the Navajo people being against naming a clothing line “Navajo line”. A lot of the designs however, personally I don’t like them. Such as, brightly colored moccasins or moccasin soles being made from rubber. Some people do like these which, is fine for them, just not me. My moccasin soles are made from deer hide. My jewelry is made from either myself or my brother.

I may not be 100% American Indian but, I read, write and speak the Tsalagi (Cherokee) language. I know the history and customs of my ancestors. Those of you who dare challenge my ancestry because I am not 100% American Indian, can you say the same? I believe it is not what is running through your veins but, it is what is in your heart that matters.

Wado

It’s a two way street here! Native Americans need to get out of that way of thinking that everyone who isnt native american is out to get them because of the troubles they have faced in the past and some still to this day. I am an Aboriginal from Canada and I think that it is awesome that people actually agknowledge that we were the “true designers” if you want to look at it that way. I get theyre making money off of Native American fashion but I think people should try look at it in a positive way. At least the Native Americans are getting agknowledged for there good taste in fashion . I say be proud of it! Just because youre not making profit off of it doesnt mean you can bash people who chose to sell and wear the fashion. I dont see any of the people complainigng about it out there making profit off of “your fashion” ..

But here’s the rub: when my husband and I traveled from Reno to Louisiana, to transport his mother’s household goods, we passed MANY Indian shops hawking, what we thought were Indian wares. Some were in gas stations, run by obvious indians. On our way back home we stopped to peruse these shops,( that weren’t gas stations and we stopped only for gas and sleeping) and were disappointed to find “China” marked on the bottom of most things. The real indian crafts were locked in cases. There were some beautiful ponchos, they said were felted from horsehair, which is amazing to me as I would have thought they got more from their sheep, but they felt soft enough.

One shop had nice coiled baskets, made from meadow grasses, and those were likewise made in Pakistan. I asked the girl at the counter why they didn’t make their own baskets anymore, she smiled real pretty but didn’t really have an answer for me. (and a gorgeous Navajo). I make these type of baskets, I enjoy it, it centers me, and maybe it seem tedious and “BORING” to every youth today, I guess. I learned crafts in my youth and always enjoyed it. In fact I can listen to talk radio or music or TV shows while doing it, so it’s what I first learned was “multitasking”. But it felt good to do it and it feels good to get it finished.I used to feel good to give them as gifts to freinds until I saw later how they had abused my gifts.

So my point is, Indians hawk their wares to whites to make a living and I have no issue with anyone trying to make a living, we all have to do it. Sadly now there are less their own work, but still, if some want to fault whites from buying their stuff, I guess you can make it illegal for whites to be involved with the trade at all but then who are they going to sell to? And how much percentage Indian blood is acceptable? I know a few blue eyed blonds who got their “papers” and are proud of their Indian blood.

Wow! Thank you for giving me insight into what these patterns mean and how they are important. It is difficult to properly respect something when you don’t understand why it needs to be respect in the first place. This is an excellent article and you are an excellent writer. If I may ask a question, if Mildred High Elk Carpenter had great success (like say Pendleton). Would it be wrong for them to sell those patterns to people who don’t respect/understand those patterns, even though it would benefit the Native community?

Curious about Chippewa boots and if the Indian Nation receives compensation forbade if the name. I find it ironic that they claim made in USA.

As an American, I love Native American designs and enjoy wearing them for their beauty and as a nod to our shared history. To me, its about respect of the people and the blending of our American culture and shared history. I also know that the Native American community needs our support for their crafts for survival. For those who are offended, they are not the majority.

I would like to say as a white woman, I always respected Native Americans and Native American culture and their arts. That is why I

purchase Native American designs. Every culture has Art to offer and as an artist I feel it is necessary to purchase these pieces of Art to keep them alive. Whether its wearable art or art to hang. The Native Americans who make and sell jewelry to non native Americans need to make a living and I would prefer to purchase the art from the Artisan. Its not because I want to take culture that is not mine and claim it. Its because I appraciate it and admire it.

I thought all you liberals and multiculturalists believed in multiculturalism, globalization, celebration of all cultures. American culture began with you and all of our American cultures have gone through hard times. At least yours is cherished. Remember imitation is the highest form of flattery. Celebrate belonging to the mix or at least get over your priveledge.

I chose to come into this life as a white women, to expirance life in this body through its perspectives and lessons, I wore many color skins prior to this life. So did you. I find that I belong and see myself in each and everyone of you, however I feel greatly alone. Most of the world still chooses to Divide and have not awaken. Those who have not awaken will not see that I am you and you are me. Do not judge skin, they could be your ancestors coming back to see things differently. Why have you come back? What have you learned? What have you done for others? LOVE ONE ANOTHER.

It’s interesting The Dude’s sweater from The Big Libowski was mentioned because he wears an appropriated Guatemalan Mayan pattern as his pants. In the 90’s and apparent today, the MacArther Park neighborhood of Los Angeles would have been a enclave for Guatemalan immigrants, many of whom speak various Mayan dialects. For a movie that takes place in L.A. it’s a subtle, yet unconscious, reference to indigenous culture that typifies diversity & cross-culture appropriation in LA. Hell, the costume designer likely went to MacAP to buy Jeff Bridges pants! Or a thrift shop, still appropriation. This Dude is a Grungy proto-hipster ;)

BTW great article! The topics addressed here are the very topics being addressed in my Contemporary Indigenous Arts class. Good thing I discovered this article in time!

I have a question and comment. All insights are welcomed by me…even if they may seem harsh. I create art and crafts…mostly watercolor illustrations and wood burning pieces. I have always been told we have some American Indian in our family. However without doing a lot of research I have no way of knowing how much or from which tribe my people came.

That said…

As an artist all of my life I have been inspired by the world around me in nature. Especially the smaller things that most people would walk past unnoticed. Tiny flowers so small it is hard to see the shape of their petals are a fine example. It hasn’t been until recently (I am 45) that I feel inspired to add shapes and patterns that could be seen as American Indian. They are in my mind…I don’t know if they come directly from things I’ve seen. I have not sold any of these in fear that I will be offending a culture. I may have some small amount of American Indian in my family tree but my appearance is that of my father who was half Irish. So I am pale with loads of freckles. I don’t want to be the white lady who is offending a culture. And yet this art it’s in me my …minds eye will not let it go!

How do I move forward? Because this causing me much grief.

FYI…most of my art is animals or anything found in nature.

What a great article! I’ll be sure to share

I thank the author for bringing to my awareness the reaction that commercialization of very precious cultural articles can have for my indigenous sisters and brothers. I also thank those who shared what they think and feel on this subject. I am not a Native American but of mixed European descent. I believe that every cultural group of humankind has a right to feel pride in the ways of their ancestors as to spiritual, aesthetic, language, and arts. I recognize that each cultural group bears a collective “sin” of making war at some time or another on those of another group and while everyone loves to be a victor, humanity has evolved to an awareness that we lose more than we gain when we make war and subjugate one another. Some cultures were lost through assimilation such as many of those in Europe who conquered each other thousands of years ago. Others like our Native American peoples have sustained their own ways and I am grateful to learn from your nations what other ancient peoples also knew but did not survive to teach us. I know that collectively and individually many Native American people still feel marginalized. Nothing can undo trauma, but material restitution can come about and has been slowly. I want to say that the people of the world need your culture to survive, and maybe that is why Spirit stayed with you throughout the decades of oppression. Please make a place for us who were not born in your ways to find them through your eyes and hearts, and please stand tall and firm on your identity. The way of the world is moving toward globalization, but I hope that the cultural uniqueness of each of the bands of humanity of all races can sustain their oneness sufficiently to carry on as a nation of their unique kind, respected and cherished for the way that Spirit’s light is reflected in their facet of the human prism.

Good to bring awareness for Indigenous Artists to be recognized for their art. However, Pendleton Woolen Mills is not owned by Native Americans/Indigenous. Their designs are so-called native inspired. Is that flattery, not really, as I know people that have had their art work used without their permission. In addition to this topic, many of the museums in England, the art work in those is titled “Acquired”. As for myself, I am Indigenous American Native and an artist, and if I buy Indigenous Art, I buy authentic in support of them. People need to appreciate the true and natural art for every nation in the world.

Growing up in Northwest Montana, we lived near the Blackfeet, and Salish-Kootenai tribes. As a child, I always admired their physical beauty, cultures and beliefs, but was mocked by my white community and family. As an adult and teacher, I keep posters of tribal lands, reservations and famous quotes by Native American Indians in my classroom. My students always ask me questions. I try to expand their knowledge of the people that were here before Europeans. I choose to honor the indigenous cultures, by wearing native designs and even own a teepee tent (which I hand painted) for camping which attracts a lot of attention. ( I would have preferred to buy one decorated by a real artist) I wish to support indigenous artists. No disrespect is meant by me when wearing Navajo/Pendleton designs.

I am deeply troubled by this false information. I am Sioux and Cherokee. I bought from Native Patterns thinking it was made by my distant family but I was fooled. I am so sorry.

Really enjoyed your article as it’s highly informative. I appreciate your writing about Native American fashion. It will be very helpful. Thanks for share