Chinese jewelry and objects of adornment are exquisite puzzles: Why does a delicate, wafer-thin pendant feature a pair of catfish twisting upon each other to create a yin-yang? What’s the meaning of the kingfisher feathers that have been inlaid, cloisonné-like, on a gilt-metal hairpin? And could someone please explain the story behind all those lotus blossoms, which can be found on everything from earrings to belt hooks?

“One dealer went to China in the 1970s and brought back buckets of jade.”

The puzzles found on jade jewelry are particularly rich. Whether it’s the rare, emerald-green jadeite from Burma or the more common mineral, nephrite, which ranges from off-whites to sage-greens, jade is treated with great deference in China, where it’s considered a link to spiritual realms. Today, the carved stone is also a symbol of a more earthly pursuit—market speculation on the part of dealers and collectors alike. In fact, in some circles, jade has become a preferred substitute for paper money, especially when it’s time to dispense a few key bribes.

Understanding the iconography on Chinese jade jewelry helps explain why these pieces are so prized. It’s not just the satisfaction that comes from solving the puzzle—for the record, the catfish symbolize a happy marriage, kingfishers are associated with longevity, and the lotus stands for harmony. Rather, the symbols on Chinese jewelry reveal the often single-minded traditions that have guided Chinese civilization for thousands of years, and continue to this day.

Top: A hairpin made with inlaid kingfisher feathers, courtesy the Shyn Collection. Above: The two cats symbolize marital fidelity, while the bat on one of the cat’s backs stands for blessings.

Terese Tse Bartholomew has spent her life living among Chinese symbols and motifs, including almost four decades as a curator of Himalayan and Chinese decorative art at the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco. Despite her impressive resume, Bartholomew, now retired, takes a very down-to-earth approach to the pieces that have been her life’s focus. Sitting with her in her San Francisco home, Bartholomew is not self-conscious about the pieces she holds in her hand, despite the fact that some of them are hundreds of years old. Lifting them to the light, she handles them respectfully but familiarly, like one would treat an old friend. With every new object she shows me, another puzzle piece falls into place.

“This is mutton-fat jade,” she says of a small pendant that resembles an open box with a lotus flower carved into it. Mutton fat is the colorful description for an almost colorless (but not white) form of nephrite. The rock, Bartholomew says, came from China’s Xinjiang province in Central Asia. As for the imagery: “When you see an open box and a lotus flower, it means ‘may you have a harmonious marriage’. This would have been a wedding present.”

Carved nephrite lock pendants such as this one from the 19th century were given to infant boys to protect them. The peony is a symbol of wealth.

If the meaning assigned to these symbols seems random to you, it’s probably because you don’t speak Chinese. As Bartholomew writes in “Hidden Meanings in Chinese Art,” ostensibly unrelated objects (for example, bats and peaches) are often combined to create what she calls “auspicious concepts” (in this case, blessings and longevity). Certain groupings of objects create visual puns, or rebuses, in the same way a drawing of an eyeball, heart, and sheep can be read as “I love you.”

“The Chinese language is conducive to punning,” Bartholomew writes, “because it contains many words that share sounds (and tones).” In the example above, a female sheep is called a “ewe,” which has the same sound as “you.” “Similarly,” she continues, “plays on words flourish in Chinese, in daily speech as well as in decorative art.”

That’s the first key to solving the Chinese-jewelry puzzle. The second thing to know about Chinese jewelry is its purpose. Because of its value, jade was frequently given as a gift to mark major family events such as births and weddings. As such, pieces of jade jewelry became vehicles for expressing good wishes and positive sentiments. Think of them as three-dimensional greeting cards, but with an exceptionally high degree of artistry.

Jujubes and peanuts (these are carved from agate) are symbols of fertility. In particular, the Chinese word for jujubes is a homonym of “early arrival of a son.”

A major preoccupation of Chinese iconography concerns the education of a family’s sons. For roughly 2,000 years, advancement in Chinese society revolved around how well one’s son did on the Civil Service Examinations, which ceased in 1911 when Sun Yat-sen led the overthrow of the Qing Dynasty. “When the Republic of China was set up, that was the end of the Civil Service system,” says Bartholomew. “But that history is why Chinese parents today are always pushing their kids to study. Even though the Civil Service is gone, they still push their children. It’s a 2,000-year-old thing.”

Thus, jade objects are often decorated with three round rings. “That means, ‘may you give birth to a son who can pass the three Civil Service examinations’. In China, the only way to get ahead was to pass the exams. There was the provincial one, which you’d take in your provincial capital. If you passed that, you took the next one in the capital of China (different dynasties had different capitals; during the Qing dynasty, 1644-1911, it was in Beijing). The last test was given right inside the palace. If you passed all three, you were set for the rest of your life.”

Interestingly, despite the American stereotype about Chinese students being math whizzes, mathematics was not a part of the Civil Service test. “It was all about literary skills because these people were going to be officials,” says Bartholomew. “They had to be able to write reports, letters to the emperor, that sort of thing. Penmanship was very important; you could not make a mistake.”

The three pieces of fruit in the beak of this nephrite bird express the wish that the wearer’s son may be the top scholar in all three Civil Service Examinations.

You also had to be eloquent, which meant being able to write an essay based on a classic phrase from literature, and to know where the phrase came from. And you had to understand both the mechanics and artistry of poetry—test takers were required to compose a poem on the spot. It doesn’t sound like a system that could be gamed, but according to Bartholomew, with so much at stake, cheating was a real problem.

“People cheated,” she says flatly. “They’d write down important things on handkerchiefs, on their bodies, on little books. The Suzhou Museum in China has a handkerchief with important passages from major books written on it in tiny, tiny characters. All kinds of cheating went on.”

Of course, the only people who got a chance to cheat on these tests were boys, which is why many so pieces of jade jewelry bear emblems of hope for the birth of sons. Again, the lotus was employed to communicate this sentiment. “The lotus has many meanings,” says Bartholomew. “In Chinese, you can either call it he which means harmony, as in harmony in marriage, or lian which means continuous, as in the continuous birth of sons.”

Flower-basket earrings made of silver with polychromed enamel. Courtesy the Shyn Collection.

The onus for producing a son was entirely the responsibility of the wife. “When you got married,” says Bartholomew, “there was only one thing on your mind: you wanted a son, immediately. So you’d wear a charm like this one of a boy being carried by a Chinese unicorn, which we call qilin. It brings prosperity, and even though it actually has two horns, people call it a unicorn anyway. The boy is dressed up as the first scholar. It was not enough to have a boy; the boy had to be smart and pass the exam better than anyone else. That’s what mothers wished for.”

Even if a boy did not have his sights set on being the first scholar, the pressure was still enormous. “Test candidates would commit suicide right inside the examination hall,” says Bartholomew.

Not surprisingly, perhaps, monogamy was not as important a virtue as producing a son. “If you didn’t give birth to a son, your mother-in-law was liable to force your husband to take a concubine. There must be somebody to carry on the name of the family. That’s why women wore jewelry that was all about good marriages and giving birth to sons. It was taken very seriously.”

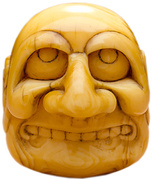

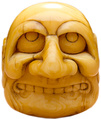

This Qing Dynasty piece of nephrite is carved to resemble Buddha’s-hand citron, which in Chinese is a rebus for blessings and longevity.

Once a son was born, he would be “protected” by decorative talismans shaped like locks. The idea was that when the boy wore it, he’d be locked to earth so he wouldn’t die. “Wealthy families gave their sons jade, gold, or silver locks,” Bartholomew says, but even families of limited means made sure their sons were tethered to terra firma. “When a son was born to a poor family, his parents would go to 100 families and ask for a penny from each to buy an inexpensive silver lock. In this way, he was protected by 100 families.”

The lock is not the only object whose meaning in Chinese jewelry is related to its actual purpose or physical characteristics. For example, pomegranates are filled with seeds, so naturally they symbolize fertility, specifically for the birth of many sons.

Peaches, on the other hand, are symbols of longevity due to their association with the legend of Xiwangmu, the Queen Mother of the West, whose orchard in the Kunlun Mountains was filled with magic peaches, which were famously gobbled up by the Monkey King. “The magic peach trees bloom every 3,000 years, and the peaches on them take another 3,000 years to ripen. When that happens, you have a peach party, and if you eat one of these peaches, you will achieve immortality.” That’s why, says Bartholomew, peaches are associated with birthdays.

Animal motifs on these silver rings include birds, lions, and frogs. Courtesy the Shyn Collection.

The meaning of bats is purely homonymic. Bats are said to bring blessings because the word for bat in Chinese, fu, is a homonym of “blessing.” Moreover, bats are often depicted flying upside down because the word for that, dao, sounds like the Chinese word for “arrived.” Thus, upside-down bats translate as “blessings have arrived.” Often, bats are depicting in quintets to signify the five blessings: longevity, wealth, health, love of virtue, and a peaceful death. “It’s the best way to die,” Bartholomew says.

“If you didn’t have a son, your mother-in-law might force your husband to take a concubine.”

In recent years, the market for Chinese jewelry has exploded in the United States and other Western countries as buyers from China have scooped up pieces confiscated from Chinese citizens, and then sent abroad, during the Cultural Revolution in the second half of the 20th century. These pieces range from museum-quality examples of Ming and Qing Dynasty jade to modest Chinese puzzle rings, whose slender, interlocking silver loops can be nestled together to form a thicker band.

What happened, says Bartholomew, is that Chinese officials would sell bulk lots of the jewelry they’d seized to international dealers. “One dealer,” Bartholomew remembers, “a Vietnamese woman from San Francisco, went to China in the 1970s and brought back literally buckets of jade. She had a store on Bush Street, outside of Chinatown, where you could buy individual pieces for $2, $4, $5, and $20. Whenever we had a little bit of money, we would go and buy from her. Around the same time, silver jewelry like puzzle rings flooded the San Francisco market. A lot of people in San Francisco still have these rings. I wish I had bought more.”

This pendant composed of two nephrite catfish was probably a wedding gift since the fish combined with the fungus that one of the fish is biting means “may your wishes come true year after year.”

Today, the Western press has mostly romanticized the Chinese jewelry and jade market here, explaining it as a desire on the part of wronged Chinese citizens to buy back the heritage that was stolen from them during the Cultural Revolution. According to Bartholomew, though, that’s only part of the story.

“Of course people want their cultural heritage back,” she says, “but you need money to do that. The buyers are the nouveau riche. Eventually they get into antiques, and the first thing they buy are Chinese goods.”

Bartholomew says the main attraction of buying in the West is price. It’s really not a case of wealthy Chinese businessmen sentimentally rebuilding the collections of their grandparents. Rather, “Chinese buyers know they can buy quality pieces in the West cheaper than they can in China. They can then take these pieces back to China and either keep them or sell them at a profit.” Reclaiming heritage is part of the motivation, to be sure, but so is good old-fashioned speculation.

Decorative hairpins worn by the wealthiest Chinese women featured stones such as tourmaline and jadite, seed pearls and red coral, and iridescent kingfisher feathers. Animal motifs on these silver rings include birds, lions, and frogs. Courtesy the Shyn Collection.

Jade objects, especially small pieces such as jewelry, have an additional appeal. In China today, jade is a fungible asset that’s actually better for some purposes than real money. “Another reason why people buy these things is for bribes,” Bartholomew says. “You can’t hand a stack of money to an official, but you can put a piece of jade on his table. People know what that means. Jade is jade.” As symbols go, the meaning of jade is well understood.

Still, despite her career as a clear-eyed academic Bartholomew admits to having worn symbol-laden pieces of Chinese jewelry for essentially the same reasons as generations of women before her. “I wore one of these charms of the little boy riding on the unicorn,” she says, returning to the qilin she had pointed out earlier. “After I had a son, I loaned it to my sisters when they got married.” Does that mean Bartholomew believes these symbols have actual, unexplainable powers? “It worked for them,” she says with a smile.

(All images courtesy of the Asian Art Museum except as indicated. Images from the Shyn Collection were first published in “Excelling the Work of Heaven.”)

The Mao Mango Cult of 1968 and the Rise of China's Working Class

The Mao Mango Cult of 1968 and the Rise of China's Working Class

The Folklore and Fashion of Japanese Netsuke

The Folklore and Fashion of Japanese Netsuke The Mao Mango Cult of 1968 and the Rise of China's Working Class

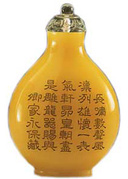

The Mao Mango Cult of 1968 and the Rise of China's Working Class The Right Snuff: Decoding Chinese Snuff Bottles

The Right Snuff: Decoding Chinese Snuff Bottles Chinese JewelryThe tradition of jewelry-making in China goes back at least to the Neolithi…

Chinese JewelryThe tradition of jewelry-making in China goes back at least to the Neolithi… Asian VasesWhether they're high-shouldered or pear-shaped, rounded at their waists or …

Asian VasesWhether they're high-shouldered or pear-shaped, rounded at their waists or … Asian AntiquesAsian cultures are among the oldest in the world and are associated with so…

Asian AntiquesAsian cultures are among the oldest in the world and are associated with so… Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Thanks for this insight into the symbols involved in Chinese jewels.

Great article! Loved the explanation of puns and rebuses…does the author mentioned, Ms. Bartholomew have any other articles explaining this? I’m studying Chinese and this part of the culture is fascinating to me.

Great article! I love the Asian Art museum in San Francisco. My visit to China in 2008 wasn’t enough – if I could I would visit China every year. I loved it! Thank you for this research article.

Just be careful of fine reproductions being sold at auction and shops

Lots if cons out there

What’s the meaning of two jade locks on a Necklace??

Impressive. In life, you never try you never know, you never read you never know. I enjoyed reading the meanings of Chinese jewelry. It’s

meaningful indeed.

It does not matter what’s the meaning of inlaying these pins with kingfisher feathers. The main thing is: the method of mining these feathers is the most vile cruelty – they were stuck the captured kingfishers on their backs or bellies, using their inability to move in this case, and pulled feathers from their living bodies. Nothing can justify this barbarity. This attitude to birds (who are the decorations, ornaments of nature by themselves) as to stones or metals, and not as to living beings. Grrr! Even the 3rd century- philosopher Bao Jing-Yan did not approve of this practice: he wrote in his treatise “The fact that a human tears out the pheasant’s feathers or plucks a kingfisher – it’s not the wish of these birds” (another translation: “If you tear off a pheasant’s feathers or rob the kingfisher’s beauty, this is unlikely to please these birds. “)

It does not matter what’s the meaning of inlaying these pins with kingfisher feathers. The main thing is: the method of mining these feathers is the most vile cruelty – they were stuck the captured kingfishers on their backs or bellies, using their inability to move in this case, and pulled feathers from their living bodies. Nothing can justify this barbarity. This attitude to birds (who are the decorations, ornaments of nature by themselves) as to stones or metals, and not as to living beings. Grrr! Even the 5th century’s philosopher Bao Jingyan did not approve of this practice: he wrote in his treatise “when the pheasant’s feathers are plucked or the kingfisher’s torn out, it is not done by desire of the bird.

I am Chinese and I am recently fascinated by ancient Chinese auspicious motifs, rebuses and designs. I would be happy to be of any help if you are interested in this field.

I have an antique jade foo dog hand carved pendant with 18k gold clasp. It has hallmarks on the base of it, and it is killing me not to know what they are or mean. I wish I could post a picture I’m sure someone could inform me. The one I’m most curious about is what looks almost like a scroll inside a circle, or a square inside a circle.