It’s easy to think of pin-up art as a charming relic of the old boys’ club—images that might line the walls of a Mid-Century smoking room where Don Draper and Roger Sterling slap each other on the back. And the names of the artists that come up over and over again are men: Alberto Vargas, George Petty, and Gil Elvgren.

“She was an icon for women in a man’s world, especially when it came to her pin-ups.”

So you might be surprised to learn that, according to pin-up art expert Louis K. Meisel, three of the most talented pin-up painters from the Golden Age, roughly the 1920s to the early 1960s, were women. “Pearl Frush, Joyce Ballantyne, and Zoë Mozert were terrific, as good as any of the men—in fact, better than many of them,” Meisel says.

That doesn’t change the fact that pin-ups were meant to be consumed by men. They first appeared in men’s magazines and break-room calendars in the 1920s and 1930s. Then pin-ups really took off after United States entered World War II in 1941, when images of wide-eyed, wholesome “all-American girls”—who just happened to have voluptuous figures and tight, revealing clothes—were sent to soldiers in the form of girlie magazines, Mutoscope cards, lighters, playing cards, etc., to remind them of what they were fighting for.

Top: Pin-ups by (from left) Pearl Frush, Zoë Mozert, and Joyce Ballantyne. Above: Regarding the Paramount Pictures “Unusual Occupations” short, “Zoe,” the artist told Marianne Ohl Phillips, “I made that fancy little costume myself. But you know, I could never paint a picture like they had me set up. Not in a million years!” Via “Tease!” Magazine #3.

“These were the girls that the boys who fought in World War II and the Korean War came back to marry,” Meisel says. “It was about getting a little house in Levittown and bringing up their two or three kids. Both male and female pinup artists painted for that.”

So Mozert, Ballantyne, and Frush were tasked with creating the ideal woman for American soldiers: young, busty, wasp-waisted, and long-legged. Her pretty face, with an occasionally coquettish expression, telegraphed childlike sweetness and a lack of real awareness of the pornographic thoughts she inspired, dancing on the edge of the virgin-whore complex. Didn’t these female artists mind portraying such an unattainable ideal?

As they say, “beauty is in the eye of the beholder.” Some people see beauty in a wide spectrum of body types and faces. Others divide the world into the beautiful people and the rest of us. From what we know about these women, it seems that female pin-up artists of the Golden Age bought into the most exclusive standard of beauty. But they themselves matched the WWII-era ideal, so they didn’t mind painting fellow members of “beautiful people” club.

A Frush pin-up captures the sweetness of the “all-American girl.”

“They were very curvy, pretty women,” says pin-up dealer Marianne Ohl Phillips, who interviewed both Zoë Mozert and Joyce Ballantyne before they died. “Both of them used themselves as models; Zoë especially loved to paint herself. From the time they were children, they thought the most beautiful thing in the world was a woman’s face and body. And none of them were gay. It is something they enjoyed painting, and they felt lucky they could make a living at it.”

“He said, ‘What’s a cute, little thing like you doing in the calendar-art business?’”

According to Phillips’s definitive 1991 article for The Betty Pages on “Zoë Mozert: Pin Up’s Leading Lady”—which has never appeared online—she “was often in papers, expounding her views on the perfect face and figure for pin-ups. Always fearless, she rated Tinseltown’s stars and starlets, a score of 100 being perfect. Scoring over 95 were Ida Lupino, Jeanne Crain, Mary Anderson, and Peggy Knudsen. Some glamour girls who didn’t measure up were Veronica Lake, Dorothy Lamour, Barbara Hale, Loretta Young, and Lana Turner, all receiving scores of 60 or less. … ‘The perfect face and the perfect figure have yet to be combined in one woman,’ she stated.”

In this Joyce Ballantyne pin-up, a girl swoons over red roses from her sweetheart.

While Mozert, at least, was not above mean-girl snarking on friends and celebrities with less-than-ideal figures, she and the other pin-up artists were still blazing a trail for women. What little we know about both Mozert and Ballantyne reveals that they had outsized personalities that gave them the gumption to succeed in a man’s world.

“I think they would consider themselves feminists,” Phillips told me. “I probably would, too.”

Still, Meisel, the co-author of several authoritative books on pin-ups, says that he can tell whether a pin-up was painted by a man or a woman just by looking at it.

“If you really get into it, you begin to see that women have a different way of portraying women than men do, even when they’re all trying to do something sexy for a pin-up calendar or a magazine,” Meisel says. “There is a certain sexy look, with black stockings, garters, and emphasis on certain parts of the anatomy that Elvgren, Vargas, and other male pinup artists do. I would say that the women portray very beautiful, idealized women, but the images are less erotic.

Ballantyne says that the pin-up was all about the tease—hinting at nudity, but not actually showing it.

“With Pearl Frush, for example, her girls were very beautiful, with wonderful-looking bodies, but it wasn’t so much about being sexy as being the all-American girl. She had less emphasis on breast size and legs than the male artists,” he continues. “Zoë Mozert was often her own model. Usually, she painted a different face, but she used her own body. And I guess in doing so, she had a different idea of what she should look like to men than maybe men would.”

“Before the 1970s women’s movement, nobody thought that pin-ups were objectifying.”

But Phillips, a paper dealer who helped bring pin-ups back into fashion in the late 1980s and ’90s, says she believes the women were naturally better at painting women. In her piece, which was reprinted in Tease! Magazine #3 in 1995, Phillips asserts, “It is infinitely logical that these exquisite creatures were painted by a female. No man, no matter how knowledgeable, can be as familiar with the feminine form as a woman.”

“You find mistakes in the male paintings,” Phillips told me. “Elvgren’s got a famous painting where she’s got two left feet, and there are just these things that don’t fit every once in a while. The women never made those mistakes. I think they looked in the mirror a lot and they got things more right. The men tended to make the breasts larger, and they made the legs longer. The women tended to paint very proportionate women, more of a 36-26-36 look, whereas men would make them a little top-heavy.”

This Ballantyne is a rare woman-painted pin-up featuring black stockings, garter belt, and heels.

Meisel isn’t denying that these women had talent. The founder of Meisel Gallery in New York City, Meisel says he helped establish photorealism as a collectible genre of painting. With his late business partner, Charles G. Martignette, he started hunting down the original pastel or watercolor paintings that pin-up posters and calendars were based on in the 1970s. They were the first to acknowledge pin-up painting as fine art and hang the works of Vargas, Elvgren, and Mozert in gallery shows.

In fact, in their book, “The Great American Pin-Up,” Martignette and Meisel often compare Frush to esteemed pin-up artist Alberto Vargas, who is much-celebrated today for his centerfold and cover work with Esquire and Playboy. Meisel explains that Pearl Frush is one of the most technically proficient watercolor photorealist painters he’s ever seen.

“When it comes to watercolor, I’ve seen the best that exist. Fifty years ago, Pearl Frush was way ahead of everybody,” Meisel says. “Face-wise, she is on the level of Alberto Vargas. Her paintings are not as sexy, but when it comes to painting a face, nobody surpasses Pearl Frush. It’s too bad that she wasn’t with a bigger publishing company.”

Many pin-up lovers consider Pearl Frush to be talented on the level of renowned “Esquire” pin-up artist Alberto Vargas.

Largely, the stories of these women have been untold. One of the problems is that pin-up illustration, like most commercial art, was hardly considered worth saving until Meisel and Martignette came along. The two went on a detective mission to salvage the original artwork done by pin-up masters.

“No man, no matter how knowledgeable, can be as familiar with the feminine form as a woman.”

“At the time, they weren’t sold in art galleries where people paid money for them,” he says. “They were given away. If your company had purchased 5,000 calendars from Brown & Bigelow, the salesman would show up and say, ‘Gee, Mr. Smith, this is the original painting that’s on the calendar you bought from us. Would you like it?’ And he’d say, ‘Oh, yeah, I’d love that.’ When he was unwrapping it at home, his wife would say, ‘Oh, you can’t put that in our house. What’ll the minister think when he comes here?’”

As a result, Meisel says, many pin-up paintings got stashed away in attics and basements. Often, the unframed artworks, done in pastels, would end up smeared. The two managed to recover originals by many major artists, but by 1990, an original Pearl Frush remained elusive.

A trend in pin-ups in the ’50s was cowgirls, as seen in this Frush painting.

“So Charles went out to Joliet, Illinois, where the Gerlach-Barklow calendar company was based. He spent a week there, where he went to the town hall and library, looking through annual reports and articles about the company. He came back with the names of 17 people whom he determined were executives at the company during that time.

“One morning, he calls up a woman in Wisconsin, and he says, ‘I understand that your father was an executive at Gerlach-Barklow. Did he ever bring home any artwork from there?’ She says, ‘Oh, yeah, we got some portfolios in the attic.’ At 11:00, Charles is on a plane from Florida, and at 4:00, he lands in Wisconsin. At 5, he’s having tea with this lady, talking about her father and waiting. At 6, they go to the attic where she shows him a portfolio with 24 Pearl Frush original watercolors from two calendars. He bought them on the spot.”

Another problem is documentation, explains Deanna Dahlsad, a pin-up collector, writer, and web publisher who blogs at the site Kitsch-Slapped, “specializing in bad taste from a (feminist) chick’s perspective,” as well as others.

Mozert poses with pin-up artists Rolf Armstrong (left) and Earl Moran. All three were among the “Big Four” artists for Brown & Bigelow calendar company. Via “Tease!” #3.

“So many women are left out of historical records,” Dahlsad says. “Men will say, ‘I want to show off what my father did; he deserves to shine. Someone should do a book on him!’ Daughters don’t do that about their moms to the same degree, so often things get thrown away. How many men would look at their archives say, ‘Just take it all to the dumpster’? Somebody would be saying, ‘You can’t do that! You’re George Petty. Put it back!’”

Fortunately, Phillips, who discovered Mozert was still alive in 1990, reached out to the artist 23 years ago. The budding pin-up dealer living in Iowa, traveled to Sedona, Arizona, just to meet this icon and learn from her, but when The Betty Pages put out a call for anyone with information on Mozert, Phillips ended up writing a 13-page profile on the artist.

“My first impression upon meeting Zoe Mozert was astonishment,” Phillips wrote in her article about the 5-foot-tall painter, who was 83 at the time. “This tiny, graceful lady had such presence, she seemed to fill the whole room! Within minutes, Zoe was flirting shamelessly with my husband, Jerry, who immediately fell under her spell.”

At 52, Mozert painted the world’s largest reclining nude for the Red Dog Saloon in Scottsdale, Arizona, in 1959. “Red Dog Rosie,” based on a picture of herself, is taller than the artist was. Via “Tease!” #3.

To me, Phillips confides, “We became friends. I spent weeks with Zoë, and after that, I would visit regularly and clean her house. She could be temperamental. Just before I published the article, she called and said she didn’t want it published. I went ahead and did it anyway, then sent her a copy. She was just so thrilled with it. She called and was quoting it, too. I thought that was so cute.”

“It’s a shame nobody wanted to hang up pictures of beautiful men in their garages.”

When Mozert passed away in 1994, Phillips discovered the state of Arizona was planning to raze her home built on a mesa. “Her property was worth a fortune, but the house wasn’t,” says Phillips, who called the state to alert them to the historical treasures inside. The officials let her claim everything the Mozerts left behind. “It was a horrible mess. All these valuable papers were mixed in with cat-food containers. I had to go through it all and put it in trash bags and ship it back here.”

Mozert’s brother Bruce had already rescued the original pin-up pastels, but Phillips was able to save the artist’s photos, invoices, and diaries from the bulldozer.

One of Mozert’s glamorous “girl heads,” featuring her brother’s perfect pout.

“She always lived as if everything was a headline,” says Phillips, which seems like the right fit for a woman who briefly joined a circus. “She had a service that would cut out all the clippings about her across the country, and so she had these scrapbooks. A lot of the newspaper articles were just things that obviously she had done to get attention, like have a pet monkey, and get it in the paper. Now I have all those scrapbooks.

“My whole life centered around men and art. Men were easy to come by; and my paintings were my children.”

“She was a prolific photo taker, too,” Phillips continues. “I found all her model photos, and just zillions of pictures of her with all four of her husbands. There were some drawings that were wadded up, but mostly it was her ramblings. She just wrote on the back of everything. She also would write diaries on everything. It was very hard to read her writing. I deciphered lots and lots, but I probably haven’t deciphered it all. Sometimes she was angry, and she drank quite a bit at the end. She was very into philosophy and homeopathic medicine, so she would write about that.

“I uncovered her letters as well. She used to correspond with pin-up artist Ted Withers. She fancied herself in love with him, so she wrote a love letter to him. There was also his letter to her, turning her down gently. He wrote like an old-fashioned Southern gentleman.”

As a young woman, Mozert modeled for fellow pin-up artist Earl Moran.

Zoë Mozert’s story

Mozert, the most famous of the top three female pin-up artists, was born Alice Adelaide Moser in Colorado Springs on April 27, 1907, to Jessie and Fred Moser, a painter and wood sculptor respectively. Gifted at carving patterns used for the scrollwork on stoves, Fred founded Moser Pattern Company in Newark, Ohio. Naturally, young Alice revealed her artistic gifts early. “The story goes that her mother placed a Bible, a silver dollar, and a pencil in front of her when she was only two years old. Zoe grabbed for the pencil and began making marks,” Phillips wrote.

Chicago ad man Doan Powell designed Mozert’s trademark signature.

In 1924, the 17-year-old was admitted to the Philadelphia School of Industrial Art on scholarship, and her illustration instructor, Thornton Oakley, had been a student of Victorian artist and writer Howard Pyle, who illustrated adventure books for youth featuring legends like King Arthur, Robin Hood, and Aladdin. Mozert lost her scholarship and had to get a job her third year, thanks to a minor scandal—she’d posed nude for an art class at another college nearby.

At age 26, Moser moved to New York City to pursue her career in art. True Story Magazine was the first to buy one of her “girl head” pastels of her sister Marcia for $75, and while she waited for her career to take off, the 5-foot-tall Mozert worked as an artist’s model.

“Around that time she decided her name was a handicap,” Phillips explained in her piece. “People found it all too easy to treat the tiny 85-lb. Alice like a child and not take her seriously. So she substituted a ‘Z’ for the ‘S’ in Moser and added a ‘T’ to make it high at both ends. Then, leafing through dictionary until there were no more pages left, finally came up with ‘Zoe’ (pronounced ‘Zo’ee,’ as in showy.)”

Phillips says Mozert made her wholesome all-American girls look at least 17 years old.

Soon her whole family, her mom, her dad, her brother, and her sister, changed their last name to Mozert. When Zoe got a gig painting cosmetics ads, her brother Bruce and sister Marcia would pose as a besotted couple, and the three would be written up as “The Royal Family of Art,” given that they descended from Robert the Bruce of Scotland. Her brother was also her favorite lip model, for images of women.

“’Those lips you’d love to kiss’ in many of Zoe’s early paintings are really the lips of her brother,” Phillips wrote. “‘They had a more definite, better outline than my own or Marcia’s,’ said Zoe.”

Mozert shows her work to Errol Flynn and Eleanor Parker, the stars of 1946’s “Never Say Goodbye.” The artist served as a consultant and provided the art for the film, which features Flynn as a George Petty-type pin-up painter. Via “Tease!”#3.

In five short years, Mozert had taken the illustration world by storm. By 1938, she had already painted 400 covers for movie magazines like True Confessions, worked with major publishers like Dell, Fawcett, and King Features, and created images for ads for Kool Cigarettes and Dr. Pepper. That year, she landed a prestigious gig to produce six covers for Hearst’s American Weekly Magazine, and at one point, she had nine covers on nine different magazines on the newsstands at the same time. On the social scene, she was known for her pithy “Zoeisms,” like “Always keep yourself bigger than your job.”

Of course, the petite woman had to have a big personality to keep the men from running her over. She told Phillips she never got along with fellow pin-up great Rolf Armstrong, who was aloof, but George Petty was a pal on the party scene.

“We met, in 1938, when we were judges for the Miss America Contest in Atlantic City,” Mozert told Phillips. “James Montgomery Flagg, the artist who painted that ‘Uncle Sam Wants You’ poster, was also a judge. Well, Flagg was a mean, old sourpuss who didn’t get along with his wife; so he hit on me. He said, ‘What’s a cute, little thing like you doing in the calendar-art business?’ Just then George rolls up and says to Flagg, ‘Listen here James, we’re lucky we made it—she earned it!’ Then he proceeded to flirt outrageously with me. I returned the compliment!”

One of Mozert’s beloved nude pin-up girls.

Ever an adventurer, Mozert took a job as photographer’s assistant on a cruise ship to South America in 1939, and there, using a photo of her friend Swann Marlowe, painted her first nude, which was hung in Mendelssohns Gallery in New York two years later. This inspired Mozert, at age 33, to take up pin-up art. Studying the work of Petty and Elvgren, she made several more nudes, which she sent to David Smart of Esquire.

“I thought Mr. Smart was terribly handsome and he was attracted to me, too.” Mozert told Phillips. “You could feel it in the air. Esquire was considering me as a replacement for Vargas and Petty.” While Smart did commission more paintings from her, eventually buying 12 of them, none ever ran in the publication.

But that didn’t keep Mozert down. When the art director of the nation’s biggest calendar company, Brown & Bigelow, saw her nude painting at the gallery, he sought her out to offer her a contract. Another nude pastel of Swann became the company’s top seller of 1943. This led to a 26-year relationship with the firm. Then in 1942, Mozert produced a series of Victory Girl Mutoscope cards for B&B, meant to be sent to the troops serving in World War II. Eventually, Mozert became one of B&B’s top four artists, along with Moran, Elvgren, and Armstrong.

A Mozert cover for “True Confessions.” She is said to have been influenced by the styles of male contemporaries Earl Moran, Gil Elvgren, George Petty, and Rolf Armstrong.

And Mozert did, in fact, pose for many of these pin-up paintings herself. According to Phillips, she would position her camera and adjust the lights using a large mirror, change into something skimpy, and have her assistant Sunny Johnson take the snapshot. While Mozert often painted her own body, Sunny would typically pose for the faces. “While walking down a street in St. Paul one day, I noticed a soldier eyeing me up and down,” Mozert told Phillips. “‘The face isn’t familiar,’ he was murmuring to himself, ‘but that body…’”

In 1943, the 36-year-old moved to Hollywood with her husband (the second of her four short-lived marriages). Paramount Pictures decided to include her in a film series called “Unusual Occupations,” with a short called “Zoe” about “the pin up girl who paints ’em too.”

During World War II, Mozert painted Victory Girls for Mutoscope cards meant to be sent to soldiers fighting overseas.

It wasn’t long before Mozert made her mark on Tinseltown. Howard Hughes recruited Mozert to paint the publicity image for 1945’s “The Outlaw,” a scandalous billboard of buxom Jane Russell in a peasant blouse dropping dangerously off her shoulder. Mozert also consulted and provides the art of the set of 1946’s “Never Say Goodbye,” which starred Errol Flynn as a George Petty-type character.

At age 45, Mozert retreated to Arizona, where she kept painting calendars for Brown & Bigelow, who was paying her a pretty penny by 1952, around $5,000 per image. In fact, she received a letter from Brown & Bigelow that read, “The price that you are being paid for the girl head is more than we are paying for any other subject in the line, except Norman Rockwell’s.” By 1953, however, under pressure from church groups, B&B asked her to “tone down” her nudes and make them more “pure.” She told Phillips she did, but the company held off on printing them.

Jane Russell models for Mozert, who’s painting the scandalously sexy promotional art for 1945’s “The Outlaws.” Via “Tease!” #3.

Mozert kept painting until 1985, when she injured her shoulder in a fall. “My whole life centered around men and art,” she told Phillips. “Men were easy to come by; and my paintings were my children.”

Joyce Ballantyne Brand’s story

Joyce Ballantyne, 11 years Mozert’s junior, did have real living, breathing children. In fact, Cheri, her youngest daughter with her second husband Jack Brand, became an American icon as a toddler, after Joyce created the attention-grabbing Coppertone billboard featuring a dog tugging down a little girl’s swim trunks.

Ballantyne and her famous daughter were tracked down in 2004 by Tampa Bay Times reporter Jeff Klinkenberg, who visited them in Ocala, Florida, just two years before the artist passed away. “I did not bring a martini shaker with me to Ocala, but I should have,” Klinkenberg wrote. “‘Mind if I smoke?’ she asked in a nicotine voice. ‘My whole house is my ashtray.’ [She] gazed across the table at me through giant pink eyeglasses and the haze of cigarette smoke. I got the feeling she knew how to handle hayseed reporters.”

Joyce Ballantyne, 86, lifts a martini glass to a reporter at her Ocala, Florida, home in 2004. Photo by Stephen J. Coddington/Tampa Bay Times.

Ballantyne was born in Norfolk, Nebraska, in 1918, near the end of World War I. She told Klinkenberg, she “liked drawing and making paper dolls; during the Depression she sold paper dolls for a buck apiece. She said she habitually entered art contests and won a scholarship to Disney’s School for Animation in California. She remembered the day when the Disney representative heard her girlish, teenage voice over the phone and rescinded the scholarship. Women married and had babies and gave up careers, she was informed. A woman was a poor investment.”

After studying at the University of Nebraska and the Academy of Art in Chicago, Ballantyne got a job with King Studios, illustrating a dictionary for Cameo Press and painting road maps for Rand McNally in the 1940s. According to Klinkenberg, by 25, she had married artist Eddie Augustiny, with whom she would have a daughter named Coby, and—as would be expect of a free spirit—learned to fly airplanes.

After a few years at King, she took another position at Stevens/Gross studio, where she worked for 10 years, which brought her into the prestigious “Sundblom Circle,” led by the creator of the Coca-Cola Santa, Haddon Sundblom. Top pin-up artists and illustrators including Gil Elvgren, Al Moore, and Al Buell were also in this club. In fact, Ballantyne’s art is most closely associated with Elvgren.

A titillating page from a Ballantyne Artist’s Sketch Pad calendar.

“Gil Elvgren, the most important pinup artist of all time, was very good friends with Ballantyne, and they actually posed for each other,” Meisel says. “When she got an assignment to have a couple sitting in a restaurant, Gil Elvgren would be the waiter, that kind of thing.”

In 1945, Elvgren recommended her to Brown & Bigelow, who started looking for new artists during World War II, as many pin-up painters had been drafted. Introduced as “the brightest young star on the horizon of illustrative art,” she designed a B&B direct-mail “novelty-fold” brochure. Eventually, she was allowed to produce a 12-page Artist’s Sketch Pad calendar, which showed the steps to drawing each image, for the firm.

“She was an icon for women in a man’s world, especially when it came to her pin-ups,” her friend Ed Franklin told the Ocala Star-Banner. “She was beautiful.”

Ballantyne caused a stir when she painted this topless mischievous mermaid for the family-oriented outdoors magazine “Sports Afield.”

Klinkenberg agreed with that assessment. “Even closing in on 90, Joyce is an attractive woman. As a young woman, she resembled the Donna Reed in ‘From Here to Eternity,’ only earthier. Often she used herself as a model, gazing into the mirror while painting a buxom doll who later would be admired in a greasy garage by drooling auto mechanics.”

At some point, she divorced Augustiny and remarried dashing TV announcer Jack Brand, who modeled for her, too. The Brands ran among a glamorous scene, populated by celebrities and artists, who’d throw late-night penthouse parties in Chicago and Manhattan, laden with martinis and pipe tobacco.

Outside of her work for B&B, Ballantyne also took assignments with Sports Afield magazine, which hired her for illustrations regularly for 20 years starting in 1947. Her first cover image was of a voluptuous mermaid, modeled after herself, pranking fishermen by putting a tire on their hooks. It caused quite a stir with readers; it seems they weren’t expecting such a sexy image on a magazine about wholesome family hobbies.

Like her friend and colleague Gil Elvgren, Ballantyne specialized in putting girls in accidentally sexy situations.

But her biggest break came when the Shaw-Barton calendar company hired her in 1954, when she was 36, to paint a 12-page calendar. Her 1955 calendar was such a hit that it had to be reprinted multiple times. This success led to gigs making more sexy calendars for Louis P. Dow company and Goes Lithography, as well as doing images for Esquire and Penthouse magazines.

“Women married and had babies and gave up careers, she was informed.”

“Mine always had some clothes on or at least a towel on,” Ballantyne told Klinkenberg. “I didn’t go in for dirty stuff like they do today. The trick is to make a pin-up flirtatious. You want the girl to look a little like your sister, or maybe your girlfriend, or just the girl next door. She’s a nice girl, she’s innocent, but maybe she got caught in an awkward situation that’s a little sexy.”

Unlike other pin-up artists, Ballantyne never got away from advertising illustration. She did work for Ovaltine, Sylvania TV, Dow Chemical, Coca-Cola, Pampers, and Schlitz. And in her later years, she made it clear that she was rather cross that she’s still best-known for that Coppertone suntan lotion ad. “Just another baby ad,” she told Klinkenberg. “Kind of boring.”

Ballantyne and her daughter, who modeled for this ad at age 3, were so bored with the iconic Coppertone baby.

It started when Coppertone asked illustrators to submit ideas for a billboard commission. Ballantyne won the job in 1959 and created the image of a pig-tailed girl who finds a dog pulling down her swim trunks, which was loosely based on an idea by pin-up artist Art Frahm. She posed Cheri, who was 3 years old then, in the backyard, snapped some photos, and drew the image.

Those famous bare butt cheeks and tan line were plastered all over the United States with the slogan “Don’t Be a Paleface!” Before long, that image became a cultural benchmark, associated with summer fun in the sun and beach vacations. And poor Cheri Brand Irwin has spent her life dodging endless lascivious comments about her back end.

In 1974, the Brands moved to an old three-story building in downtown Ocala, Florida, to be near her family. The 56-year-old artist was none too happy trading the glitz of the big city for small-town life. She told Klinkenberg, “I’d go to a paint store for supplies and would literally find a sign on the door that said, “Gone Fishing.’ I didn’t think I’d be here long.”

A rare male pin-up (possibly based on Ballantyne’s husband, Jack Brand) for one of Ballantyne’s Artist Sketch Pad pages.

Ballantyne’s husband died of lung cancer in 1985. Cheri and her husband moved into the top floor of her building to take care of the artist, who kept drinking her evening martini and smoking cigarettes until her death in 2006.

Pearl Frush’s story

Of the three, Pearl Frush is the most mysterious. In their book, Meisel and Martignette explain that her tendency to paint in watercolor and gouache made it difficult reproduce those works in large numbers. But she also used pastels when needed, and “readily commanded the respect of the art directors, publishers, sales managers, and printers with whom she worked.”

In fact, it’s hard to pin down an exact birthday for her; she was born in Iowa, and her family moved to the Mississippi Gold Coast when she was little. One rumor has her birth in 1897, via the 1900 census. Most sources say she was born in 1905.

This Pearl Frush painting in particular calls to mind the work of Alberto Vargas.

When applying for a job at Brown & Bigelow, she wrote, “I started drawing, like most children, as soon as I could hold a crayon. I guess I enjoyed it more than most children because I kept at it and was soon begging my mother for paints, modeling clay, etc. She was cooperative but not enthusiastic, as she believed that artists starved in garrets and only became rich and famous after they were dead.”

She studied art in New Orleans, Philadelphia, New York City, and finally at the Chicago Art Institute. In 1931, she married a man named Charles Warde Brudon and began signing her paintings “Pearl Frush Brudon.”

In the early 1940s, she opened a studio in Chicago for freelance work in advertising, and took assignments with Sundblom, Johnson & White. Then starting in 1943, she made a splash at Gerlach-Barklow, who published several of her most successful pin-up calendars including Liberty Belles, Girls of Glamour, and Glamour Round the Clock.

Frush loved swimming, so she painted a lot of water-sports scenes, enough for a whole Aqua Tour calendar.

Meisel and Martignette describe her as a “vigorous and attractive woman” who loved swimming, canoeing, sailing, and tennis, so it’s not surprising that many of her pin-up played sports, as in her Sweethearts of Sports calendar. In 1947, Gerlach-Barklow published her Aqua Tour series, depicting women in watery settings, which broke the company’s sales records.

By 1955, Frush had divorced Brudon and married Robert Mann, with whom she moved to Atlanta. She would also sometimes sign her work “Pearl Frush Mann.” Applying to Brown & Bigelow that year, she wrote, “I didn’t turn out to be much of a musician, but I married one. My husband, Bob, plays cello in the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra and writes music. He also plays trumpet. For excitement, we play chess almost every day and usually getting in three or four games. I win one out of three and keep hoping to improve.”

According to this letter, Frush may have been a little more shy and humble than Mozert or Ballantyne, which might be part of the reason she produced less work. She started the letter to B&B with “I’m afraid my history is not very exciting.” And finished with, “Sorry, I don’t have my recent photos. I dislike having my picture taken except for snapshots.”

A pretty-girl gouache by Pearl Frush at the height of her artistry. Via GrapefruitMoonGallery.com.

As one of the most important artists at Gerlach-Barklow, she was seen as a rising star in the pin-up industry, so B&B quickly hired her, publishing its first Frush pin-up in 1957, a single-page hanger calendar, with a horizontal image. At this point, she was at the height of her career, producing almost startling photorealistic images. In the 1960s, Robberson Steel Company of Oklahoma City was so happy with their Frush advertising calendars from Gerlach-Barklow, they commissioned her to do a series of glamour paintings, the last one in 1974.

There is no known death date for Pearl Frush, whose middle name is usually listed as “Aleryn.” But Ancestry.com has a Pearl Alice Frush listed as dying in 1985 in Decatur, Georgia, survived by her husband Robert Goodell Mann of Atlanta.

“Altogether I don’t think there are a hundred images of Pearl Frush around the world,” Meisel says, musing that she didn’t get the chance to do enough.

Publishing companies like Shaw-Barton hired pin-up artists to produce art for calendars, like this piece by Ballantyne, which reads “You don’t think I’m flat, do you?” Other firms, mostly in masculine industries like plumbing, would order a certain number of pin-up calendars with their names and addresses printed along the bottom.

Of course, the era of the illustrated advertising pin-ups started to fade in the 1960s and 1970s, as the technology for reproducing color photographs got better and better. And Meisel also blames the rise of feminism and political correctness. “Before the 1970s women’s movement, nobody thought that pin-ups were objectifying,” he says. “It was the all-American girl.”

“The ‘lips you’d love to kiss’ in Zoe’s early paintings are the lips of her brother.”

“The easy breezy flirt girl who isn’t showing too much skin, she still exists,” counters pin-up collector Deanna Dahlsad, who mentions that she runs into more female pin-up collectors than male. “But as women entered the workforce in the 1970s, it was no longer acceptable to put out pin-up calendars in the break room at the office. Or to give them as gifts to your best salesmen, because they might be saleswomen.”

Dahlsad also wonders if Frush, Mozert, or Ballantyne ever felt conflicted about creating these innocent-but-sexy women to be ogled at factories and mechanic shops. “When you’re a commercial artist, you take jobs that pay you,” she says. “If that’s where all the money was, as a woman, you’d be lucky to get that job.”

Mozert seemed quite satisfied being an object of lust, but she did admit to Phillips, “It’s a shame nobody wanted to hang up pictures of beautiful men in their garages. But business was business, and one had to meet the demand.”

Everyone throws their cat out for the night in a translucent nightgown, right? This is a recurring theme in Ballantyne pin-ups.

(For more information on female pin-up artists, check out Louis K. Meisel and Charles G. Martignette’s “The Great American Pin-Up.” If you buy something through a link in this article, Collectors Weekly may get a share of the sale. Learn more.)

Va-Va-Voom Vintage: Dita Von Teese on Burlesque, Cars, and Lingerie

Va-Va-Voom Vintage: Dita Von Teese on Burlesque, Cars, and Lingerie

Girlie Glasses: A Peep Show With Your Beer

Girlie Glasses: A Peep Show With Your Beer Va-Va-Voom Vintage: Dita Von Teese on Burlesque, Cars, and Lingerie

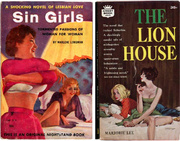

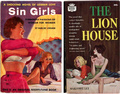

Va-Va-Voom Vintage: Dita Von Teese on Burlesque, Cars, and Lingerie When Being a Lesbian Was Profitable, For Men

When Being a Lesbian Was Profitable, For Men Pin UpsIt wasn’t until the 1800s that technology had advanced enough to allow arti…

Pin UpsIt wasn’t until the 1800s that technology had advanced enough to allow arti… Girlie MagazinesBack in the Victorian Era, many Americans believed that if a man squandered…

Girlie MagazinesBack in the Victorian Era, many Americans believed that if a man squandered… Fine ArtFor as long as there have been civilizations, humans have made art to inter…

Fine ArtFor as long as there have been civilizations, humans have made art to inter… Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Congratulations on a great article, Lisa!

The paper trail for Pearl Frush turns up a birth record for her: 20 Mar 1907, Sioux City, Iowa. Interestingly, she is listing herself as a self-employed artist as early as 1930 in the census as well as in 1940! She was just 23 at the time.

Thanks, Vetraio50! And thanks for heads up, pin-up fan. :)

Great article!

This was a very fascinating and inspiring article that I thoroughly enjoyed. Being an artist who can relate to being draw to the female face and figure as a source for inspiration and study.I just really enjoyed it.thank you.

Lisa, this turned out to be a real swell article — thanks for including my thoughts :)

Fantastic article. One of the best I’ve read on any topic in a while!

Excellent piece. Fascinating women.

I loved this article! I’ve been fascinated with the pin-up girls since I was just a youngster back in the 50’s and got to look at some Esquire magazines laying around at a friend’s house. I was surprised to read that 3 of the best artists turned out to be women. What a very interesting article & I loved ALL the pictures.

Thanks for such a wonderful article. Great work!

Superb article.

Among my earliest memories as a young man and budding painter, was discovering the pinup girl poster on the inside of a cabinet in my grandfathers workshop. I’ve been a fan of classic pinup art ever since.

Just after reading this (followed the link from http://twonerdyhistorygirls.blogspot.com) I heard this interview on NPR – http://www.npr.org/2013/05/31/187350487/sex-overseas-what-soldiers-do-complicates-wwii-history

I love the pin-ups! Since I began working at Heritage Auctions (HA.com), I have been exposed to works from all of the major pin-up artists because we sell so many of them, including works from these three talented women. Thank you for a well written article!

I also knew Zoe Mozart at the same time as Phillips. I cleaned her house, did errands for her and was a companion to her. There were a lot of sketchy people approaching Zoe Mozart during this time, trying to get her to sign agreements signing away the rights to her paintings. I tore up countless “arrangements”. She was not always in her right mind during that time period. She tried giving me all of her original art. I would not take it. Many people tried to take advantage of her. I would love Phillips to contact me. I always wondered what happened with her belongings once the county took control of her life.

It disturbs me that all a man has to do to get women to want what he wants them to do is get a female actress or model to propagate it. I see people sticking up for females in pop culture as expressing freedom, when we all know men control the music industry and if a girl dresses a certain way it is because some man told her to. So how is doing what a man tells you equal female liberation? I just want women to be aware that men still control most things especially the entertainment industry and to be aware of who is behind things marketed towards them. Just because a woman acts it out it doesn’t mean it isn’t a man’s point of view. Before going to film school I though art reflected life, but after learning they call them self the culture industry I realized media exists to program people it is literally called television programming.

My mother, Dollis Payne, created some absolutely beautiful paintings of pinup girls in the 1950’s. She passed away in 2013, and my sister and I inherited her paintings/drawings. They are stuffed away in drawers and it pains me greatly that they won’t be displayed or sold to someone who would know how to care for them. The paper that they were painted on is getting a bit old. If anyone could give us some tips on what to do with them or how to care for them, it would be very appreciated.

Really nice article. I’d love to know what you think of my website, http://www.mutoworld.com . It started as a compendium of my collection of Mutoscope pin-up cards ( alas, lost in a house fire in 2012 ) and so I have not updated it. I’d suggest to Helen that she contact Mr Meisel for an evaluation. He is easy to find and a very nice guy.

Very enjoyable, but will not understand the reason 4 shoes in the beach

paintings…Thank you

Qoute: “In her piece, which was reprinted in Tease! Magazine #3 in 1995, Phillips asserts, ‘It is infinitely logical that these exquisite creatures were painted by a female. No man, no matter how knowledgeable, can be as familiar with the feminine form as a woman.'”

What a fallacy. There are male artists out there who are far more accurate in realistic depictions of human anatomy in general than any of these pin-up artists (male or female). Pin-up art isn’t seeking mere realism–it’s an appeal to fantasy. It’s deliberate exaggeration, based on realism. But any number of classical artists have these pin-up artists beat, in terms of high-fidelity anatomy and realistic detail.

Oh, and while a woman might have far more familiarity BEING a woman, you don’t have to actually be a woman to know how to observe well and capture its form well. Saying being a woman makes you better at drawing women is like absurd. Looking at yourself in the mirror only goes for far. Even women study the form of other women in order to draw it well. Even as a man, you don’t actively study your own form everyday. A first-person view of yourself only goes so far.

Quote: “You find mistakes in the male paintings,” Phillips told me. “Elvgren’s got a famous painting where she’s got two left feet, and there are just these things that don’t fit every once in a while. The women never made those mistakes.”

This has nothing to do with the sex of the artists–only the attentiveness of the artist. I’m sure that, as human, some of these women made mistakes in their work SOMEWHERE in their work. Just as Elvgren was bound to make a human goof as he did. If a woman had made the same mistake, it wouldn’t (shouldn’t, anyways) be held against her as woman–just as human.

Not that high accuracy was particularly the goal in pin-up art, anyways… High likeness is the overall goal. Nobody’s noticing those details so much–such details weren’t the point of pin-up art. The fact that most viewers didn’t even notice Elvgren’s two left feet attests to the sex appeal which was the picture’s focus.

Quote: “I think they looked in the mirror a lot and they got things more right. The men tended to make the breasts larger, and they made the legs longer. The women tended to paint very proportionate women, more of a 36-26-36 look, whereas men would make them a little top-heavy.”

Noooo. You don’t say?

The whole point of pin-up art is exaggerated sex appeal. NATURALLY, the men are going to portray the women with larger breasts and longer legs–we adore those things. It’s already fantasy being portrayed here–you exaggerate those things to heighten sex appeal.

Just how making the women in pin-up art being more proportionate as “right,” as to imply that more exaggerated forms are “wrong,” is something I question with scrutiny here. Proportionate accuracy isn’t exactly the point of pin-up art.

HELP, I purchased 6 (maybe) wine? peep-show glasses @ an estate sale in a small town in Texas, abut 10 years ago. The older gentlemen was very fond of them, but his wife was not so “crazy” about them! He stated that he had bought them in Germany during World War ll . There is an etched marking on the back of the glasses that states “0.25” & D.O.B. underneath and some framing partially around the numbers and letters. I would be so happy to have any more information on these (in my eyes) Awesome Pieces of Art!!! Thank you…

having been both a dealer and collector of this era of pinups for over 40 years, I found this article to be a wonderful asset that gives credence to a long overlooked yet greatly admired profession .

You guys didn’t mention one word about an artist I really like Gene Pressler. He didn’t do all pin up art but some of the images he did are great.

Sure was a great article well researched and written as per THAT research. NOW with what we are going through with plenty of time on hands, and rereading tons of things. Agree with almost all the comments. NOT #15. If you know and spoke to Zoe and Joyce, you would know they painted what and how THEY WANTED!!! #19 has made a good contribution and is RIGHT! #22. I know the works of Pressler. He WAS a good artists, but his work has nothing to do with THIS article, and hence, not mentioned.

A fascinating article and it tells us more about the elusive Pearl Frush – well done.

Female artists continue to contribute to the Pin-up genre – notably Olivia de Berardinis and Giovanna Casotto as my own walls can attest – sadly my painting by Joyce Ballentine has been sold but it was enjoyed for years. Giovanna continues Zoe’s habit of using herself as a model.

There was nothing better than to hear Charles Martignette recount his stories of recovering paintings that no-one else valued at the time and the story of recovery of the Frush paintings rings only too true.

You mentioned pastels several times but didn’t specify which kind. Do you know if these were the soft, chalky style – or the more paint-like oil pastels? I am an oil pastel artist with a website devoted to the medium and would love to know if you know this answer. Many thanks either way.