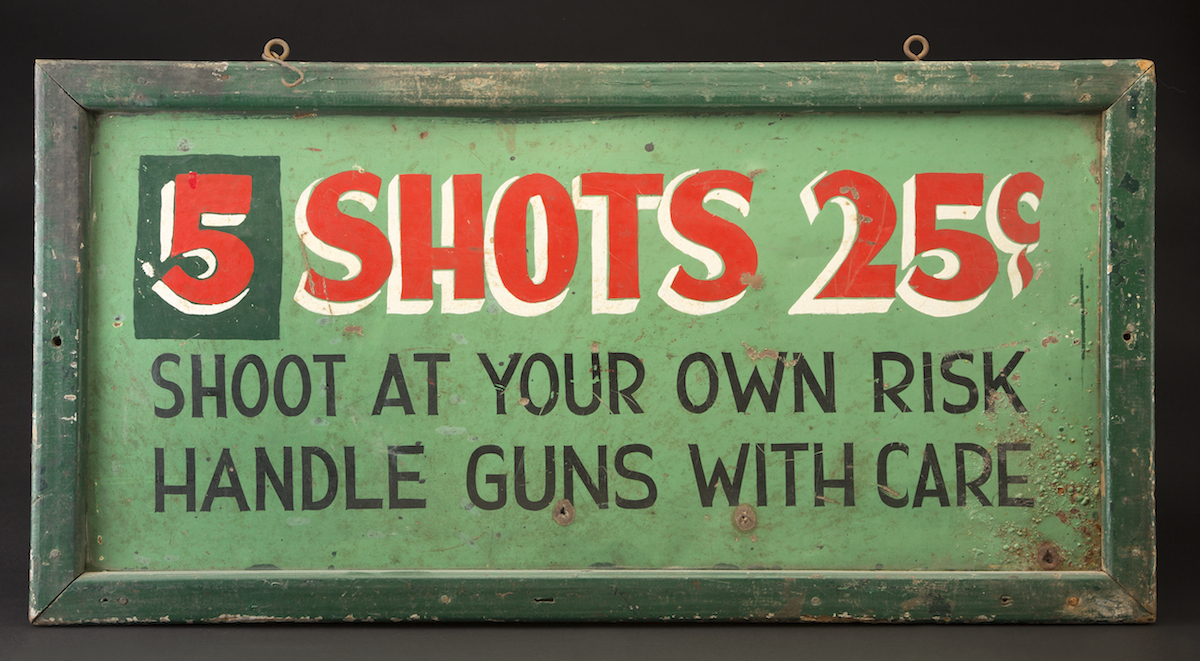

It used to be that if you felt the sudden urge to shoot something but found yourself without a gun, all you had to do was hop a streetcar to the local amusement park, stroll over to the midway, and toss a coin into the sweaty palm of a cigar-puffing carny. In return, he’d hand you a loaded .22 caliber rifle and wish you luck. Taking your place alongside other kindred shooters, you’d survey the cheerfully painted ducks, rabbits, cowboys, and Indians moving from side-to-side or bobbing before you, take aim, and fire! If you hit enough of these pockmarked pieces of cast iron, you won a prize, although the pleasure for most was probably in pulling the trigger.

“You’d almost need a bazooka to make it spin.”

Today, the notion that it was once considered perfectly normal to deliver a rifle filled with live ammunition into the hands of anyone with some spare change in their pocket seems absurd—a tragedy waiting to happen, followed by a costly lawsuit. Indeed, the liability issues surrounding the casual distribution of loaded weapons in public places helped kill .22 caliber shooting galleries, which were replaced by arcades designed to receive the less-lethal impact of air-powered BB guns and pistols that shoot pressurized streams of water.

Many people, though, still set their sights on those cast-iron targets from the late 19th and early 20th centuries, which are collected as a form of Americana or folk art. In the eyes of at least one collecting couple, arcade targets may even be considered progenitors of the bull’s-eye paintings of mid-20th-century artists Kenneth Noland and Jasper Johns.

“Johns was living downtown in New York City, not very far from Coney Island,” says Richard Tucker, who, along with his wife of 50 years, Valerie, has just written a new book about targets and arcade memorabilia called Step Right Up!: Classic American Arcade and Target Forms. “We don’t think it’s a stretch to say he may have been influenced by the targets in the arcades and shooting galleries out there.”

Top: Rooster with Star, probably manufactured by William Wurfflein. Above: Rowdy Target, manufactured by Wm. F. Mangels.

The Tuckers were not similarly influenced. They began with modern and contemporary art, which they started acquiring in the late 1970s. “We lived in Fort Worth, Texas,” he says. “I was a lawyer and Valerie was an educator. We started collecting contemporary art when you didn’t have to be a billionaire to be able to afford a Jasper Johns, Claes Oldenburg, or whoever it was. But then the prices escalated so dramatically, and quickly, that we basically got priced out of the market.”

That was in the “Go-Go ’80s,” when the fortunes being made on Wall Street and a sudden demand for European Impressionism and Post-Impressionism by Japanese collectors warped the art market beyond recognition. Coincident with this hyperinflation, the Tuckers decided to move to a working horse ranch outside of urban Fort Worth. “We moved to a country farmhouse, so we sold most of our collection of large-scale paintings and sculpture and started collecting folk art and Americana,” including, Richard says, windmill weights, which is how the couple first became interested in figural cast iron.

While the subject matter of the contemporary art they collected varied widely, the pieces had an important trait in common, their textural surfaces, which was another link for the Tuckers between the targets at Coney Island and the paintings of some of the most renowned American artists of the 20th century. “I think what always stuck with us through the years was the surface,” Valerie says. “The surfaces of the contemporary paintings we had correspond to what we’re doing now with the targets. We love surface—that’s always been our prerequisite of our collection.”

In a Johns painting, that means a thick, luscious, encaustic surface that gives the piece physical dimensionality while imbuing it with an instant sense of history, which is a neat trick considering that when Johns paints a painting, it is, by definition, new. In contrast, the texture of a cast-iron target’s surface is earned the hard way, a record of its endurance against the impact of countless .22 cartridges. The dinged surfaces of the best targets resemble the hammered copper exteriors of Arts and Crafts era vases by master coppersmiths such as Dirk van Erp, so uniform are their indentations. Those that have been painted often appear mottled, with rust-tones poking through the once bright greens, reds, and blues that were applied to lure would-be shooters. Still other targets are pure patina, suggesting years of being pelted by gunfire out in the elements. And then there are the targets that don’t appear to have been fired upon at all—time has left its mark gently on such fortunate forms.

While the surfaces and motifs of the targets varied, the ways is which shooters interacted with them was largely the same. Electricity powered the conveyor belts and wheels that made the targets so difficult to hit, but technology was not advanced enough to automatically tally a shooter’s score. “There was always a carny operator there,” confirms Richard, “because someone had to collect the money and help you load your rifle. There could have been some kind of a wooden scoring mechanism, but I think it was more of an optical thing, where the carny would just note what you shot and how many you hit in order to determine what kind of prize you got. The galleries were relatively small—some were portable enough to be loaded onto the back of a pickup and driven from town to town—so it was easy to keep track of a shooter’s points.”

Points were tallied when a target was struck, knocked over, or sent spinning in place when shot on one side or the other. From the shooter’s point of view, the arcade was a game of skill. From the standpoint of the carny who was pocketing quarters from the great unwashed, not so much. A horse carrying a rider wouldn’t just move from right to left, it would rock, making it more difficult to hit the rider. But the most deceptive targets were some of the spinners, some of which featured extra-thick bases compared to the ones they might be placed next to, making them all but impossible to turn from the impact of a .22 alone. “On some of those,” says Richard, “you’d almost need a bazooka to make it spin. When you see these things head on, you really don’t realize how thick they are, and how difficult it would be to create a winner.”

These details and more fill the pages of Step Right Up!, which is co-authored in places by many of the mentors and friends the Tuckers have gotten to know in the niche world of arcade-target collecting.

“Steve and Ronelle Willadsen were some of the earliest people we met when we started collecting in this area,” says Richard of the couple who wrote the text for the chapter on a target manufacturer named William Wurfflein, whose father was a 19th-century Philadelphia gunmaker. Young William, the Willadsens tell us, shifted the focus of his father’s business to targets, winning awards for his work at the Centennial Exhibition of 1876, held in Wurfflein’s hometown.

Box of Remington .22 Short Cartridges.

Bob Goldsack contributed the chapter on C.W. Parker of Kansas, a late-19th, early-20th-century manufacturer of “amusement devices,” who called his company “The World’s Largest Manufacturer of Shooting Galleries.” Goldsack has written an entire book on Parker, says Richard, but even he does not know if this hyperbolic claim is true. What he does know is that of the Parker targets that have survived, and few have, many show no evidence of ever having been painted at all. Instead, the metal was left to patina, resulting in hues that range from gunmetal gray to chocolate brown.

“Richard and I are going all over the country trying to tear down walls.”

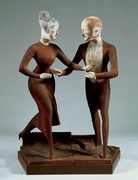

For the chapter on W. F. Mangels Carousel Works, the Tuckers turned to Jeffery Abendshien, who tells the tale of Coney Island’s own amusement-device manufacturer. Like Parker, Mangels made carousels and other attractions for the carnival industry, but the characteristic that really set Mangels apart from competitors was the ingenuity of his mechanical galleries. Mangels targets, which have a decidedly folk-art appearance, were usually attached to a chain device that Mangels called the “Slide.” This allowed a duck, for example, to be knocked over by a bullet, disappear from view, and then right itself on its way back into the line of fire.

Abendshien also handled the chapter on John T. Dickman, an early 20th-century amusement operator and manufacturer based in Los Angeles, which was close to the numerous “pleasure piers” that dotted the Southern California coast. Dickman’s innovations included creating stencils for his targets to make them easy to repaint, and designing them to be interchangeable with targets made by other manufacturers.

In fact, many companies appear to have found it more cost-effective to simply copy a Dickman design and manufacture it themselves. In particular, his Great Clown target (also known as Bright Eyes) was reproduced rather faithfully by a company called H.C. Evans, one of a quartet of Chicago-based manufacturers who did business within a few miles of each other and cribbed liberally from each other.

Or not. “Copyright laws were not near what they are today,” Richard says. “In the Chicago manufacturer catalogs, you’ll see the same bird or duck, over and over. Sometimes the only differentiation will be the part number. In one catalog, the duck might have a 32 on it, in another catalog it might be marked with a 52, but it’s the same exact duck. Which leads you to an interesting question: Did they steal each other’s merchandise and basically just reproduce it, or were they all using a subcontractor who had a foundry and was making all this stuff for them? We don’t know the answer to that. That’s one of the mysteries that make collecting this material so intriguing.”

Card Suits, manufactured by Wm. F. Mangels.

Nor, say the Tuckers, is it clear how successful these companies even were. “Most of the Wurfflein targets we have acquired still have remnants of what looks like original paint on them,” Valerie says. “It’s as though they hadn’t been repainted. A lot of these pieces were designed to be repainted a couple of times a year.”

“If you go through the Wurfflein and Parker chapters,” Richard adds, “you’ll see many targets in their original surface. We can’t account for why that is, other than that maybe they had never been used. They may have been more like salesmen samples than pieces that were used in an actual gallery.”

Adding to this mystery is the fate of the galleries themselves. “We’ve only seen a complete, operational gallery by one manufacturer, and that’s Mangels. A Parker gallery? A Wurfflein gallery? The Chicago manufacturers? None of these companies have galleries that have survived. And so you ask yourself, what happened to all of the galleries? Why is Mangels the only one who had a gallery that survived? There are no oral histories, and no written records or documents have survived to give us a clue as to why so much of this material is one-of-a-kind.”

“Unless a lot of it was melted down for war purposes,” Valerie offers.

“Sure, that’s a possible answer, but why only Mangels? We have a few photographs in the book of Dickman galleries from California, but other than artist renderings and catalogs, there’s no evidence of surviving material made by any of the other manufacturers. Was Wurfflein all hype? Parker claimed to be the largest shooting-gallery manufacturer in the world. If so, why have no Parker galleries survived? Sometimes you wonder if they even made any of this stuff at all.”

Of the few galleries that have survived, the stories of how they were discovered are similarly intriguing. One shooting gallery in Ohio was revealed during a restaurant remodel. The gallery, which proved to be in full working order, had been boarded up behind a wall. “So now Richard and I are going all over the country trying to tear down walls,” Valerie says.

The Tuckers found one, too, but restoring it and setting it up for public use proved unworkable. “At one time, we found a complete gallery out at Coney Island,” Richard remembers. “It was another one of these stories where the gallery had been boarded up and was behind a wall. We thought we might buy it because we had a friend who ran a country-western honky-tonk in Fort Worth. We were going to put the gallery in his honky-tonk, but those conversations quickly came to an end because nobody wanted to accept the responsibility and potential liability behind it.” Apparently, even in open-carry Texas, the prospect of handing loaded weapons to patrons of a bar was simply too much.

Seven years ago, the Tuckers left their beloved horse ranch in Texas and moved to a residential neighborhood in Boulder, Colorado, which meant it was time again to refocus their collecting strategies. “We had literally thousands of pieces of Americana, folk art, smalls, painted furniture, and so forth,” Richard says. “When we moved into a traditional house here to Boulder, we just didn’t have all the space and storage room we once had, so we sold off a lot of smaller stuff, including many of the smaller targets. At one time, we probably had maybe 350 or 400 of them.”

“Our grandchildren counted them the other day,” Valerie continues. “They counted 125 in the house, so we probably have 150 total.” The couple also let go of many of the pieces that got them interested in arcade targets in the first place. “We had a huge collection, some would say the pre-eminent collection, of cast-iron windmill weights,” Richard says. “Last year we sold 153 pieces to a single collector. So we are now down to 25 or 30 very rare pieces that we can display here in our home.”

“Our next collection will be handkerchiefs,” Valerie promises. “We’re getting too old for all this heavy iron.”

(Step Right Up! is published by Schiffer books. If you buy something through a link in this article, Collectors Weekly may get a share of the sale. Learn more.)

Jeepers Creepers! Why Dark Rides Scare the Pants Off Us

Jeepers Creepers! Why Dark Rides Scare the Pants Off Us

Ordinary Beauty: How 'Folk Art' Challenged the Art World to Get Real

Ordinary Beauty: How 'Folk Art' Challenged the Art World to Get Real Jeepers Creepers! Why Dark Rides Scare the Pants Off Us

Jeepers Creepers! Why Dark Rides Scare the Pants Off Us Where Have the Carousel Animals Gone? Antique Merry-Go-Rounds Fight Extinction

Where Have the Carousel Animals Gone? Antique Merry-Go-Rounds Fight Extinction Arcade GamesArcade games encompass a variety of coin-operated machines found in amuseme…

Arcade GamesArcade games encompass a variety of coin-operated machines found in amuseme… Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fascinating!

You could make an interesting collection/article on the rifles used in these arcades. Some of the carneys used rifles originally manufactured for use with “birdshot” .22 short ammo. These guns had unrifled barrels (smoothbore) which didn’t impart a spin on the bullet, making it less accurate even at the short distances in most arcades, giving him an edge. Also, some would let you use your own rifle, and the average country kid who shot a lot would clean up and take home a lot of teddy bears!

what a great collectable. It brings back the “good old days” feeling that is lost in todays amusement parks and fairs. I’ve seen them and even sold them at some of my public sales, but, I never gave thought to collecting them. In the future, I will seek out these interesting artifacts for my own collection. Thanks for the wonderful article …… hotairfan

I have an old target that I found on the wall in my parents coalroom in there house in 1957. I am not a collector of targets but I do collect “old stuff” that I hang on the wall in my family room. My target is iron circle about 10″ with a bull eye in middle that releases a brass duck thatr pops up above target. There is a place to connect a rope to reset.