Mary finished her embroidery, tucking her needle away into its handsome ivory case. Before slipping the case into her sewing kit, Mary held it up to the light of a nearby window, and peered into a tiny glass lens embedded in the ivory. She smiled at the secret photograph of her favorite place—London’s Crystal Palace. In the next room, her husband, John, checked the time on his pocket watch. Making sure Mary was out of sight, John lifted the watch chain to his eye, stealing a peek at a tiny photo of a topless woman deftly hidden inside his watch key.

“It was absolutely the coolest freaking thing I’ve ever seen.”

In the mid-19th century, a few decades after the invention of photography, inventors began experimenting with minuscule “microphotographs” developed on glass slides, producing images that were all but invisible without a standard microscope. But the diminutive Stanhope lens changed that—concealed behind a magnifying glass no larger than the head of a pin, microphotographs could now be viewed with the naked eye.

Suddenly, it was all the rage to insert tiny photos into everyday objects; needle cases and watch keys (such as those in the fictional scenario above) were just two kinds of objects among thousands containing Stanhope lenses. Such novelties spread across the globe, with millions of them made over the next century. Microphotographs would even play a significant role in wartime espionage, allowing people to sneak messages over enemy lines. But today, these ingenious Stanhope devices are mostly forgotten, along with the scientific contributions of their imaginative inventors.

John Benjamin Dancer is credited with creating the first microphotographs in 1839 at his studio in Liverpool, England. “Dancer sold high-quality scientific instruments, especially microscopes, and got the idea that if he could make photographs as small as possible, then he could use them to demonstrate the quality of his microscopes,” says Jean Scott, author of the definitive book Stanhopes: A Closer View.

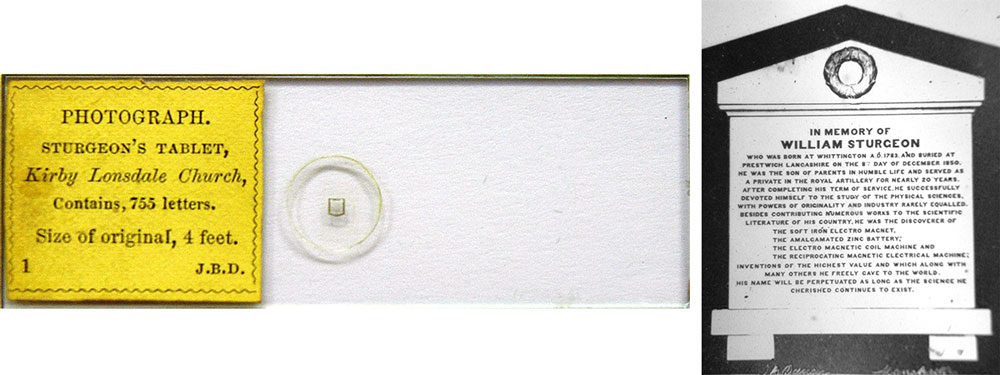

Top: A collection of sewing implements with hidden Stanhope lenses. Above: A glass slide by John Benjamin Dancer holds a microphotograph of William Sturgeon’s grave marker (click to enlarge). All photos courtesy Ken and Jean Scott unless otherwise indicated.

In 1853, Dancer was asked to photograph the grave marker of scientist William Sturgeon. Sensing an opportunity to test his new method of microphotography, Dancer printed tiny pictures of the tablet onto glass microscope slides and circulated them to Sturgeon’s friends as a form of memento mori. The overwhelmingly positive reaction led Dancer to begin producing such slides with miniature images of royalty, travel destinations, and famous quotations. Dancer sold his slides to dealers of scientific equipment and novelty shops, which marketed them as a clever amusement to pair with flashy new microscopes in modern Victorian parlors.

Dancer’s friend Sir David Brewster was given one of these photographic slides and carried it with him across Europe, along with a hand magnifier made of spherical glass known as a Coddington Lens, which allowed him to easily show off the miniature photographs. Brewster spread word of Dancer’s tiny photos far and wide, even gaining an audience with the Pope and Cardinal in Rome. But before he could get much further with this new technology, Dancer’s eyesight began to fail.

Left: A microphotograph of the French Royal Family. Right: An image of Queen Victoria celebrating the 50th anniversary of her accession to the throne.

Meanwhile in Paris, commercial photographer René Dagron was enamored with microphotographs, and hoped to improve the viewing method so that they might be more easily mass-produced. “Dagron saw Dancer’s slides being demonstrated at a photographic salon in Paris,” explains Scott, “and realized that the trouble was you needed a microscope to see them, so the slides were only available to the wealthy. It would make them much cheaper if you could combine the image and the viewing method in one object.”

Dagron spent nearly a year secluded in his workshop, perfecting a lens that would do just that. He settled on a miniature version of a magnifying device invented 50 years prior by Charles, Third Earl Stanhope, who gave these tiny lenses their name. In 1859, Dagron was granted the world’s first microfilm patent for his new device, but the following year, he simplified the design to create the most common form of Stanhope. One end of a small glass cylinder was ground into a convex form, and on the opposite end, a tiny, translucent photo (cut from a glass slide) was secured with Canada balsam, a glue made from the resin of a balsam fir tree. When held to the light and viewed from the longer side, the microphotograph was visible to the naked eye.

This champagne-pattern knife features a Stanhope with a portrait of Adolphus Busch, circa 1890s. Photos courtesy Rob Niederman.

According to local newspaper coverage, Dagron’s first Stanhope was commissioned by a client who was spurned by his lover—he had requested that a tiny portrait of her be placed into a ring mount so he could wear it without anyone knowing. However, records show Dagron’s first commercially viable Stanhope was built into a watch key, a tiny tool for winding pocket watches that most men carried around on a chain or fob. These ubiquitous little keys, typically no more than a few centimeters in length, were perfect for concealing microphotographs. As Scott writes in her book, the subjects for these photos varied from family portraits to historical events to famous artworks, for “all could be retained on a miniature image, to be admired in secret or revealed at will.” Regardless of subject matter, the public found Dagron’s photographic innovation thrilling.

Dagron quickly secured international patents for his Stanhope lens and began producing his Stanhope novelties in a variety of forms such as jewelry charms, miniature monoculars or binoculars, penholders, letter openers, and needle cases. “Dagron also invented a camera that could take several microphotographic pictures of the same object and print them on a single glass slide,” says Scott. “His camera would move a couple of spaces sideways and up and down, taking a picture each time, and the first version only took eight images at once. But by the late 1860s, he had developed a camera that could get 450 microphotographic dots on a single slide.”

The slides bearing these tiny images were cut apart into little glass squares, or “clichés” as the French called them, and pasted onto their Stanhope lenses for distribution. (In French, “cliché” originally referred to the first cast of a movable-type printing plate made to easily produce multiples.) While most had single images, some Stanhopes were composites with several photos collaged together.

Dagron’s Stanhopes quickly became the talk of Paris: A series of articles published in 1860 describes the theft and recovery of a jewelry set designed for the British royal family and attributed to Dagron, complete with Stanhope lenses featuring photographic portraits of Prince Albert, the Prince of Wales, and others. By the end of 1861, customers could order a custom Stanhope viewer via mail by including a daguerrotype or carte-de-visite of whatever they wished, and Dagron’s company would reproduce it at microscopic size. To keep up with demand, his studio and workshop expanded to nearly 150 employees, most of whom were women, while Dagron ordered his glass lenses wholesale from experienced opticians with better manufacturing facilities.

A row of tiny, bone Stanhope binoculars, which men often wore on their watch chains, and two images from a binocular Stanhope showing the famous aviator Louis Blériot.

In 1862, Dagron was invited to show his wares at the International Exhibition of Art and Industry in London. Business spiked again following the exhibition, leading Dagron to establish his own factory exclusively for Stanhope lenses, which he decided to build in Gex, France, near the Swiss border. By early 1863, Dagron’s new lens facility was fully functioning. Though the publicity around Dagron’s invention gained him a popular following, it also inspired several manufacturers to challenge him with their own patents. Despite the competition, Dagron’s company produced Stanhope lenses up through 1897, when his heirs sold the business to an employee. Even in other industrialized nations like the United States, the vast majority of lenses were ordered from Dagron’s original factory in France.

A souvenir Stanhope from Jerusalem. Photographed by Sol Legault. Courtesy of The Kinsey Institute for Research in Sex, Gender, and Reproduction.

Stanhopes were appealing for so many reasons: Before cameras were portable or affordable for most people, these little viewers provided a perfect souvenir or reminder of important events. Plus, they were so cheap they could be trashed once the imagery’s subject matter was out of date. “There were Stanhopes before there were postcards,” says Scott. “All the places people visited on holiday were put on Stanhopes. If there were newsworthy events, they produced Stanhopes for them. I’ve got a tiny pair of binoculars and on one side it shows the famous aviator Louis Blériot’s plane flying over some cliffs and the other side of the binoculars shows Blériot with his family. I have another that shows the floods in Johnstown, Pennsylvania, with the date of 1889 on it.”

Various companies also saw Stanhopes as a form of cheap marketing, like matchbooks in the mid-20th century. “There are advertising Stanhopes that I find fascinating—some with no pictures, just writing,” says longtime collector and enthusiast Howard Melnick. “In fact, I have a neat little parasol-shaped needle case whose Stanhope is actually an advertisement for an umbrella manufacturer in Philadelphia.”

Top: A selection of colorful parasol-shaped needle cases in Jean Scott’s collection. Bottom: An image from a Stanhope umbrella advertisement. Photo courtesy Howard Melnick.

“Hot air balloons, trained carrier pigeons, and secret microphotographs connected Paris with the outside world.”

Dubious press coverage at the time claimed that the English preferred Stanhopes with photos of calendars or banknotes, the Italians wanted religious imagery, and the Germans wanted more risqué fare. In fact, erotic Stanhopes were popular everywhere, typically built into objects expected to remain within a circle of male viewers. “Usually the most erotic ones are in smokers’ equipment because that wouldn’t have been used by women,” says Scott. “Since they were so tiny, nobody else would have noticed them.” Melnick points out that a nude photo in a sewing tool or scent bottle is often a sign that the Stanhope isn’t authentic.

One of the largest collections of erotic Stanhope lenses is housed at the Kinsey Institute in Bloomington, Indiana. Melnick has worked closely with the Kinsey collection—donating Stanhope objects, repairing lenses, and preparing items for display. Most of their Stanhope archive was made up of loose lenses never inserted into objects. These Stanhopes arrived as a single donation in the 1920s, when they were confiscated in the mail as pornography presumably on their way from a lens manufacturer to a client making novelty items. “There were thousands, with 30-some different images,” Melnick says. “Some are actresses with clothes on, but mostly they’re stylized nudes doing poses amid weird props or things like that.” Combining their small size and secretive placement, Stanhopes were perfect for hiding erotic imagery in plain sight.

Left: One of the erotic Stanhope lenses from the Kinsey’s collection, circa 1920s. Photographed by Sol Legault. Courtesy of The Kinsey Institute for Research in Sex, Gender, and Reproduction. Right: Many risqué photos seem more awkward than sexy by modern standards, like this topless woman from Jean Scott’s collection.

Today, hunting for Stanhopes is addictive precisely because most of these lenses were designed to elude discovery. As Melnick puts it, “most Stanhope objects don’t declare themselves to be Stanhopes.” Besides the ubiquitous miniature binoculars or monoculars, Melnick has only come across a couple of other Stanhope items that explicitly make their purpose known. “I just got a little sterling-silver charm that looks like an old keyhole, and it actually says ‘Peek’ on the charm. If you look inside, it shows six views of Montreal,” says Melnick. “I also have a celluloid pocket knife from the 1939 World’s Fair with the Trylon and Perisphere on it. The top of it says, ‘Air View New York Skyline’ with an arrow to the Stanhope, and inside is a photo of the New York harbor and skyline. Those are the only two items I’ve ever seen that direct you to the Stanhope.”

Even today, the discovery of a Stanhope lens in an ordinary object is enough to make the viewer squeal with delight. “I remember the first time I saw one, I just couldn’t believe it,” says Scott. “If you go to an antiques fair and you see somebody standing there holding a small object to their eye and looking up, you can be pretty certain they found a Stanhope. We collectors call it the Stanhope pose.”

Left: This carved bog-oak crucifix from Ireland features shamrocks, an Irish harp, and a Stanhope barely visible at bottom-left, circa 1890. Right: A microphotograph of the Holy Family from a bone rosary Stanhope, circa 1870.

Finding an object without its original Stanhope can be equally disappointing: Products featuring Stanhopes usually weren’t well-made, hence their propensity to fall apart over the last century. “Other than a few quality items, this stuff was all cheap novelty crap meant as a remembrance or souvenir,” says Melnick. “Some of the British ones had a little cotton thread around the Stanhope, and as you pushed the lens into the tube, the thread would lock it there. Others were glued in, but gluing glass to metal doesn’t last too well, and over the years they start to fall out.”

Through Melnick’s connections at the Smithsonian and the George Eastman House museum, which has one of Dagron’s microscopic cameras and spare Stanhope parts, he was able to learn how to dismantle and reassemble a traditional Stanhope lens. “That was a slow learning experience, ruining a couple of things and figuring it all out,'” says Melnick. “But that allows me to buy items that are damaged or ‘Stanhopeless and put them back together again.”

Because of the wide variety of objects with Stanhope lenses in them, they cross many categories of collectibles—from pocket watches to smoking accessories to writing implements. Many people today don’t even realize they own a Stanhope. Melnick recalls the experience of a friend working with objects salvaged from the sunken Bertrand Steamboat, the largest American collection of intact Civil War-era artifacts. “I don’t know how they got on the subject,” says Melnick, “but the conservators told him, ‘We actually have knives with glass rivets.’ And he said, ‘Really? Do you know what a Stanhope is?’ So they went and dug them out, and sure enough, they were Stanhopes—four bladed knives with two Stanhopes in each knife showing erotic lithographs from 1865. Whoever cataloged them was accurate enough to describe that there was one round side and one flat side to each glass piece, but no one had bothered to put their eye up to the lens and look inside.”

One of Melnick’s Anheuser-Busch bartender knives and an advertising image from one of the company’s Stanhopes, circa 1880. Photos courtesy Howard Melnick.

In fact, it was a similar knife that first gave Melnick the Stanhope bug back in 1984, when he was focused on collecting knives with specific uses and unique blades. Melnick spotted an interesting Anheuser-Busch knife in a catalog inset with a Stanhope lens featuring images of founder Adolphus Busch and the company’s brewery in St. Louis, Missouri. “I thought, well, that sounds pretty neat,” explains Melnick, “And for $45 bucks, I’ll be a sport and get it. When I finally got the knife, I thought it was absolutely the coolest freaking thing I’ve ever seen.

“We happened to live near one of the antique capitals of the world—Renningers in Adamstown, Pennsylvania—which was just one exit down the turnpike,” Melnick continues. “That’s where I had the epiphany about Stanhopes. I was at a collectible stand of sewing items, and I spotted something with a lens in it, and I thought, ‘Oh, my God, they’re in other things, too!’ Once I realized that, I was off and running. I even joined the World’s Fair Collectors Society to find Stanhopes.”

When Melnick first became obsessed with Stanhopes in the 1980s, few in the antiques business knew what they were. On buying excursions to markets like London’s famous Portobello Road, Melnick found many dealers weren’t even aware of Stanhopes in objects they were selling. “It wasn’t a question of whether you were going to find something; it was a question of how many items you were going to find and what they were going to be. It was unbelievable,” he says. But more recently, he and Scott have noticed dealers are more familiar with Stanhopes, making them harder to find in the wild.

Though Stanhope lenses were produced by many different photographers, Dagron’s images are still regarded as the cream of the crop. “Whether Dagron had a proprietary chemical mix or whether he just used more layers during the wet plate collodion process—I’ve heard they used 24 layers of coating or something like that—his pictures are much nicer than most,” says Melnick. “They have better contrast, and just a higher quality.” Dagron’s early images are the most prized of all, both for their quality and their history. “Stanhope collectors are very keen to get a Dagron image, and the most desirable are images that have a short form of ‘Reproduction Microphotographic by the Dagron Company,’ written underneath the images in French,” says Scott. “That was only done between about 1860 and 1870.”

No matter their quality, documenting the miniature images hidden inside antique Stanhope lenses is an arduous process. “I was one of the first to try and photograph these pictures, and I did it using a pathologist microscope at a hospital with a 35mm camera mounted on it,” says Melnick. “This was well before the digital age.”

Though digital cameras have simplified the procedure, capturing the image within a Stanhope lens still isn’t easy. “Over the years, my husband has taken a lot of photographs of Stanhope images,” says Scott, “and his method is to use a camera attached to a microscope, which is attached to the computer.” The Scotts have gotten so familiar with photographing these images that the BBC has contacted them several times for their expertise, and their imagery has been featured on the American PBS show “History Detectives.”

In 1906, a monument was dedicated to the balloonists, pigeons, and microphotographs that made communication possible during the 1871 Siege of Paris. The memorial was destroyed during World War II.

This revival of interest in Stanhopes isn’t just about their novelty appeal; it also stems from the allure of espionage. During the Siege of Paris in 1870, when the city was occupied by Prussian forces, Dagron’s invention made the leap from a cheap souvenir to an essential communication tool between isolated Parisians and the exiled government in Tours. Though today it sounds like some far-fetched steampunk thriller, Dagron helped devise a system using hot air balloons, trained carrier pigeons, and secret microphotographs to reconnect those trapped in Paris with the outside world.

Once the city’s roadways were blocked, the French Post Office quickly adopted a carrier-pigeon system to deliver short notes past the barricades. Dagron improved upon these methods by replacing handwritten letters with microphotographs.

“René Dagron and one of his associates left Paris via hot air balloon,” explains Scott, “and managed through various adventures to escape to the town of Tours, which was the new center for the French government and its post office. Dagron had devised a slightly thicker film that could be rolled up very tiny and put into a piece of goose quill, which was attached to the feathers of carrier pigeons.”

Baskets of pigeons were delivered via hot air balloon from Paris to Tours, where Dagron was compiling urgent messages for Parisians from across the country. “They had to be very short messages,” says Scott, “mainly things like, ‘We’re alright, so-and-so has escaped,’ or ‘Can you give me your bank details? I need money,’ and things like that.” If the pigeons made it back to Paris, the microfilm tubes were removed and softened in water until they could be flattened and projected for transcribing. Though many pigeons (and their messages) were lost during the Franco-Prussian war, the system still allowed some semblance of communication.

Following the war, Dagron sold souvenirs of the pigeon post complete with reproductions of the tiny messages.

After the war ended in 1871, Dagron and his family returned to a very different Paris, with its Imperial Family in exile and the tourist market considerably damaged. His family worked to regain their company’s standing, and by the time of Dagron’s death in 1900, the business had rebounded.

Even so, the status of Stanhopes had begun to change. Many of the most popular objects that held Stanhopes were becoming obsolete, replaced by new technology or sleeker versions in Art Deco or Streamline Moderne styles. Stanhopes were relegated to kitsch, their subject matter becoming ever more gimmicky, and many Stanhope manufacturers were out of business by the mid-20th century.

But a handful of French microphotographic companies continued to supply regional souvenir industries around the world and a growing American market for cheap jewelry and plastic Stanhopes. Though another family had assumed ownership of Dagron’s lens factory at Gex in 1905, they continued producing traditional Stanhope lenses until 1972.

Scott estimates that until that date, when authentic Stanhope production ceased, around 80 million novelty objects with Stanhope lenses had been made. As the device’s popularity waned, Stanhopes were thrown out or tucked away, lying idle in old jewelry boxes or writing-desk drawers. Which is why there are probably a lot of marvelous little Stanhopes still out there, waiting for fresh eyes to admire them in secret or share them with the world.

Left: A classical painting of Angélique and Médor from a Stanhope viewer. Right: A microphotograph of two girls and a parakeet from Jean Scott’s very first Stanhope, both circa 1865.

(For more information on Stanhope viewers, check out Jean Scott’s book Stanhopes: A Closer View. If you buy something through a link in this article, Collectors Weekly may get a share of the sale. Learn more.)

The Killer Mobile Device for Victorian Women

The Killer Mobile Device for Victorian Women

In Living Color: The Forgotten 19th-Century Photo Technology that Romanticized America

In Living Color: The Forgotten 19th-Century Photo Technology that Romanticized America The Killer Mobile Device for Victorian Women

The Killer Mobile Device for Victorian Women Dawn of the Flick: The Doctors, Physicists, and Mathematicians Who Made the Movies

Dawn of the Flick: The Doctors, Physicists, and Mathematicians Who Made the Movies StanhopesShortly after the invention of photography, tinkerers did their best to man…

StanhopesShortly after the invention of photography, tinkerers did their best to man… PhotographsFrom Mathew Brady's Civil War photos to Ansel Adams' landscapes to Irving P…

PhotographsFrom Mathew Brady's Civil War photos to Ansel Adams' landscapes to Irving P… Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

A terrific article delving into the history and place of Stanhopes in the pantheon of photographic history.

What a fabulous site! Rich in history, culture, art, and a roadmap of our history. Thank you.

Fabulous – an utterly captivating article. The use of Stanhope lenses in the Cold War is rarely documented – the fledgling CIA bought a number to allow agents to read instructions on microfilm – only to discover they all had risque photographs on them!. After (reluctant?) removal of the nudey-ladies, these viewers played a tiny part in defeating the Russian Bear… in another life I hope to collect these marvelous diversions…

Can stanhopes be repaired as mine is in a gold charm which was my mother’s ?

Hello…and thank you for this information. It was very interesting. Could you tell me the highest value of an authentic Stanhope cross that was ever sold, to your knowledge? In particular, I am thinking of one made in the late 1800’s. Thank you for any additional information.