A young Victorian woman stands on a beach and stares out past the crashing waves, far out into the ocean, wondering where her sweetheart is now. His ship sailed months ago, and he’s not due to return for years. She has no way to hear his voice saying he loves her. The only comfort she has is the coin in her hand. She runs her fingertips over his initials engraved on one side and forget-me-nots on the other, and she feels soothed.

“With love tokens, emotion can be felt in the palm of one’s hand.”

“Back then, any sailor who went off to sea didn’t know if he was ever going to come back,” says Nancy Rosin, the president of National Valentine Collectors Association. “And if he were coming back, it wouldn’t be for a long time. So the sailor’s farewell is a huge scene in Valentine’s Day cards. The imagery always shows the man going off in the ship and the Cupid in the trees, aiming his arrows.”

In this world before voice mail, text messages, or quick-and-easy photo snapshots, love tokens—common coins engraved with sentimental messages—offered long-distance couples tangible reminders of their bond.

Top: A dime love token from a man’s pocket-watch chain features the name “Nellie” and an arrow piercing two hearts. Above: This early love token for Sarah Whalley was probably a memorial of her death. (Courtesy of the Love Token Society)

“Emotion can be felt in the palm of one’s hand,” Rosin wrote of love tokens in an issue of the NVCA newsletter, “Valentine Writer.” “Touching those invisible dreams and fingerprints of the past seems to fulfill a promise of enduring love.”

“Schoolgirls would beg anyone they could ask for these love tokens.”

Rosin, who is also the president of the Ephemera Society of America, has collected “tokens of love” dating back to the 1400s, encompassing everything from thimbles, rolling pins, and hard-carved wooden spoons to scrimshaw corset busks, odor-blocking vinaigrettes, and paper-and-lace Valentines that have been fashioned into gifts expressing romantic love or an intention to marry. But “love tokens” are literally tokens, coins that have been taken out of circulation, sanded or scraped flat on at least one side, and engraved with letters and designs denoting a sentiment.

While love tokens can be found all over the world, they reached their height of popularity in the United States and Great Britain in the late 1800s, at a time when the populations of both countries were eager to embrace sentimentality. By 1865, nearly everyone in the United States had lost someone during the Civil War. More aware of mortality, Americans wanted to keep their loved ones close and express their feelings. In England, British subjects had followed Queen Victoria’s passionate romance with Prince Albert and mourned his death in 1861. She made it fashionable on both continents to wear jewelry revealing the contents of your heart—be it love or grief.

Two examples of treizains, or French marriage medals, from Nancy Rosin’s collection. Both have double flaming hearts, while the coin on the left has a handshake symbolizing a union. (Photos by Nancy Rosin)

Of course, the tradition of love tokens had precedence. Starting in the late 16th century, the French would fashion 13 specially carved coins, still considered valid currency, to be given to a young couple at their wedding. These treizains, which evolved into modern-day marriage medals, would be blessed by the priest during the ceremony. Rosin has a few, and clasped hands and an arrow piercing two hearts were common motifs.

In England, men would carry coins for good luck. To distinguish their charms from the rest of their pocket change, they would bend two edges of the coin in opposite directions on opposite sides. These were known as “benders,” and if men ever gave their lucky coins away, it would have to be to someone they cared about deeply.

This birth announcement, “James Bell born March 1, 1795,” was engraved on a copper British halfpence. (Courtesy of the Love Token Society)

Around the late 1600s or early 1700s, average folk in Britain figured out how to make their own designs on coins, with a technique known as pinpunching, which just required a sharp metal object, like a pin, and hammer, to pound out a series of dots. The first English coins that were actually engraved instead of pinpunched used the simple lines you see on scrimshaws, and these most often feature names and dates in honor of births, weddings, anniversaries, and deaths. Eventually, everyone from folk artists to highly skilled artisan engravers made such “engraved coins,” as they were known in England, usually from copper coins like half pennies, pennies, and two pence.

“You have to imagine how scarce things might have been and how much time someone took to carve it, perhaps staying up at night to engrave a coin,” Rosin says.

This early love token features a sun engraved with scrimshaw technique on an English half penny. (Courtesy of the Love Token Society)

Some of the most heart-rending early love tokens come from the late 1700s, when men (and more rarely women) were convicted of serious and petty crimes by the British government and shipped off to penal colonies in Australia—to return in seven years, or not at all. Soon-to-be-exiled prisoners and their loved ones would exchange love tokens, called “prisoner tokens,” with phrases like “When this you see, remember me” engraved on them.

“When people did something wrong in England, they sent them to the colonies in Australia and just left them there for years,” says Sid Gale, who is the secretary and treasurer of the Love Token Society. “A lot of love tokens were made then, but they were on copper pennies where somebody just took a nail and just tap-tap-tapped it with little dots. A lot of sentimental little sayings originated during that period.”

“When this you see, remember me” is a phrase thought to have originated on prisoner tokens, or love tokens made by British subjects sentenced to be shipped to penal colonies in Australia. This is a modern stamped reproduction of a Victorian love token. (Courtesy of the Love Token Society)

However, it’s nearly impossible to attribute an engraved penny to a specific prisoner or penal colony. “Those confirmed prisoner tokens can be quite valuable,” says Carol Bastable, the president of the Love Token Society. “I haven’t priced them lately, but they can be $1,000 coins versus an early English engraved coin with a similar design that’s not attributed, which might sell for $150.”

“At the fair, a fellow walking arm-in-arm with his girl would buy her a love token, engraved on the spot.”

Love tokens evolved separately in the United States. During the Civil War, soldiers found they had little use for the change in their pockets that they likely couldn’t spend in enemy territory. So the men would put their coins to practical use: If a soldier lost a button, all he had to do was drill two holes in a coin. Others would have their personal information engraved on coins and then keep them as a dog tag. Some coins would also be engraved as a romantic gift for a woman waiting back home.

“I was a regular coin collector for a long, long time, but antique coins were getting expensive and difficult to grade,” says Gale, who was in the Marine Corps 26 years. He says that he was at a coin show and a Civil War love token caught his eye. It was pricey for a love token, but more affordable than a mint coin from the same era, because most serious coin collectors consider engraved coins damaged goods. “A guy showed me a silver dollar that was engraved, ‘For my darling. October 16th, 1863.’ When I saw that, I thought it was either something a soldier gave to his wife or girlfriend when he left for the Civil War or something she gave to him to carry. I liked that one, probably because of my military background.”

It’s rare that love tokens will have a first and last name, as well as a location like this “Annie S. Thompson” token, at left, engraved on an 1877 Liberty seated quarter. At right, a type III gold dollar was engraved into a golden anniversary gift. (Courtesy of the Love Token Society)

Gale explains that as chromolithography became more affordable and started to replace the letterpress in the late 1800s, wood-type engravers turned to hand-engraving coins as a way to survive. By 1870s, their elaborate, beautifully engraved love tokens became a full-on obsession for Victorians, in both the United Kingdom and the United States.

“If you went to a fair in Victorian England, someone would be scraping off the side of a coin and selling love tokens,” Rosin says. “A fellow walking arm-in-arm with his girlfriend would take her to buy a little love token. I don’t know if it necessarily meant their love would last, but it was a big thing with young people.”

In the United States, the fad, according to some reports, created shortages of dimes because so many were being engraved. “Victorians were very sentimental types,” continues Bastable, who has a master’s in art education and got intrigued by love tokens when she started attending coin shows with her coin-collector boyfriend, who eventually became her husband. “During that time, people would have or carry certain things as a memento of someone else, like hair jewelry, which was made of braided hair or hair set in little rolls.”

These tokens feature overlapping initials: A “CMC” with horseshoe for a “C,” at left, and an “FW,” at right. (Courtesy of the Love Token Society)

The most common love tokens feature what’s known as “triple-overlapping initials,” with three fancy letters piled on top of one another in an intertwining pattern. “You have a limited space on the coin. I think, artistically, it was a style that made sense for a small area,” Bastable says. “It used to be believed that the tallest and slightly more narrow one was the first name, and the last name is the widest one. But studying these tokens, we’ve found there’s leeway with that. The engraver had artistic leeway in designing what letters work better wide and narrow, and he would to mix it up a little, too.”

A suitor—or a family member or friend—would give their beloved a token with their own initials. “It is a memento of a person that gave it to you,” Bastable says.

A “JG” was engraved on the reverse of an 1857 dime. (Courtesy of the Love Token Society)

When the love token didn’t feature the giver’s initials, Gale explains, often the initials on the token would mean that he was proposing marriage, before diamond engagement rings were the thing. “If a guy in 1876 wanted to get married, he could take a dime out of circulation and engrave it with the initials from his family name and the girl’s first name. If she accepted and wore it, they were engaged. That’s one of the ways you got engaged back then, before DeBeers really marketed diamonds and before there were jewelry stores all over the place.

“In fact, when I asked my wife to marry me, fortunately, I had found a love token with ‘JG,’ because her name is Judy,” Gale continues. “I gave her the ‘JG’ token, which also had a bouquet of flowers on it. She understood the tradition, that what I was saying was, ‘Do you want to change your name from Judith Webb to Judith Gale?’”

Romantic love and marriage weren’t the only reasons for giving and receiving love tokens. Those that weren’t engraved with initials might instead feature a word for the relationship. “You’ll see them engraved with ‘mother,’ ‘father,’ ‘baby,’ ‘sister,’ ‘brother,’ ‘aunt,’ ‘uncle,’ ‘cousin’— pretty much every family member you could have,” Bastable says. “I actually have one that’s engraved ‘nanny,’ so I would say that particular caretaker was regarded as an extended family member.”

Today, pocket change might not seem like anything special, but back then, coins were made of precious or semi-precious metals. For that reason, love tokens would be made into jewelry, particularly pins, earrings, and bracelets. A mother might have a bar pin of multiple dimes soldered in a row, which she wore at her collar, or a bracelet made of linked dimes or a series of dimes attached to a metal band or a hinged bangle, each coin engraved with the initials of her husband and all their children.

This silver hinged bangle features six love tokens with cut-out ovelapping initials and two with engraved linear initials. (Courtesy of the Love Token Society)

“In the United States at the time, silver was in fashion in women’s jewelry,” Gale says. “Women wore as many as five different bracelets—three on one arm, two on the other, and two or three of those would be made out of silver. They say silver was easy to engrave and affordable.”

Bastable says that the Liberty seated dime was the coin most commonly engraved into a love token, followed by the half dime and the quarter, probably because those coins worked so well as jewelry.

“Those who speculate as to why the dime was used say the size works quite well in bracelets,” Bastable says. “If you go up to quarters, it’s clunkier than what Victorians wore. A lot of the Victorian jewelry was smaller and dainty, so a 20-dollar gold coin would be a pretty massive piece to wear. If it were a pendant, it could bang up and hit you pretty hard, and if it were a pin, it could weigh down the dress.”

An exquisite example of a love-token necklace. (Courtesy of the Love Token Society)

In fact, love tokens on half cents and 20-dollar gold coins are the most difficult to find—most collectors will never see one in their lifetimes. That’s because half-cents predate the peak of the love-token fad, and before then, the giver of a half-cent token might come across as cheap. Whereas $20 was a huge amount of money back then. “It would take someone incredibly wealthy to give that as a gift,” Bastable says.

Rarer love tokens also have enameling, with black enamel symbolized mourning. Gale found an intriguing example of this, a bracelet belonging to Stephanie Bougere, the widow of Achille D. Bougere, who owned a plantation in Louisiana, not far from Gale’s home. The bracelet features eight dimes with her initials and those of her seven children, all enameled in black. It’s a rare piece of love-token jewelry whose history is known. “I have pictures of the family members,” Gale says. “We researched it and found it came from a plantation on the Mississippi River between Baton Rouge and New Orleans. I was able to speak with their descendants.”

This love-token bracelet belonged to Stephanie Bougere, the widow of plantation owner Achille D. Bougere, and it features her initials, as well as those of her seven children, Horace P., Fannie A., Clarence L., Pauline, Albert R., Achille E., and Blanche D. The coins were enameled in black in mourning of her husband. (Courtesy of the Love Token Society)

But love token bracelets weren’t just popular with married women. Schoolgirls caught on to this trend and would plead with everyone they knew for an engraved dime. “They would beg for these love tokens probably because they wanted to get enough to make a bracelet,” Bastable says. “I think they would ask anyone they could ask. There could have been girls asking more than one boy, and also family members and friends.”

Besides bracelets and bar pins, love tokens were soldered to pieces of wire to make earrings, attached to stick pens, and made into cufflinks for men. Other love tokens were chained together to form necklaces, belts, or pocket-watch chains. Some love tokens were even attached to rings, belt buckles, or chatelaines.

This 1876 half dollar was carved with the initials “MC” and made into a pinback. (Courtesy of the Love Token Society)

Collectors of love tokens are always on the hunt for rare specimens. It’s much harder to find a love token that’s been enameled (black for mourning, blue for true love), or embedded with stones (usually turquoise, red garnet, and pearl), or cut with holes or into other shapes. Similarly, collectors are fond of tokens engraved with images—which are far less common than initials, names, relations, or dates.

It’s fun to speculate what the images on these “pictorial” love tokens meant to the lovers or kin. For certain, Victorians communicated their feelings through bouquets and drawings of flowers using what’s known as “the language of flowers.” For example, a dandelion means “faithfulness” and “happiness,” whereas a gardenia might stand for “you’re lovely” or “secret love,” while bachelor buttons, not surprisingly, mean “single blessedness.”

Left, a flower love token was set with turquoise, garnet, and pearl. Right, a three-cent silver coin was engraved with forget-me-nots and linked in a bracelet. (Courtesy of the Love Token Society)

“Back then, you could send a whole message just with a bouquet of flowers, no words,” Rosin says. “People were very aware of the language of flowers, because it wasn’t considered proper to say certain things out loud, but you could create a bouquet to explain it.”

The tricky piece is that most flowers on love tokens are not jeweled or enameled to give them color, so a rose could have dozens of meanings—from love to mourning to friendship—messages that would normally be determined by color.

“On a love token, it’s a little bit hard sometimes to decipher the flower,” Bastable says. “You will see a number of forget-me-nots on love tokens. They’re pretty distinctive, and you can count the rounded petals. When the coin is not in color, you can lose some of the meaning—for example, a red carnation means ‘longing for you’ versus a yellow carnation, which means ‘rejection.’ But we know ivy can mean ‘clinging’ or ‘constancy,’ to be there for someone.”

This Liberty seated dime, part of a man’s watch chain, is engraved with a bird and an umbrella and the name, “Bessie,” who might have been one of the man’s daughters. (Courtesy of the Love Token Society)

Birds are another motif you see on love tokens. A bluebird was considered the “bird of happiness,” while lovebirds and turtle doves were known to mate for life. “If that’s the image a man is giving a woman, that could be showing his intentions to marry her,” Bastable says. “It’s not conclusive; it’s just what we can piece together.”

Some symbols are universal: A horseshoe means “good luck,” while lighthouses signify “a safe harbor.” A musical instrument or tool probably meant something more personal to the giver or recipient, like their trade or talent. “You don’t see hearts that often, but that’s what everyone would think of as an indication of love,” she says.

Left, a landscape shows a lighthouse, house, and a boat on a three-cent silver coin, which is part of a love-token bracelet. Right, a boat sails off into the sunset. (Courtesy of the Love Token Society)

Another theme you see on pictorial love tokens is the landscape. “In the Victorian period, they often spent a weekend in the country,” Bastable says. “The landscape could possibly reflect a visit to the country. Or maybe it’s a yearning to go to the country. Perhaps it was just a popular design of the period, because there were a lot of Sunday painters who painted landscapes.”

Gale says he’s found quite few that show a little boat at sea. “That might just be someone thinking about somebody they left in Europe when they migrated to the United States,” he muses. “But I don’t know. That’s the trouble with them. They can’t talk, so they can’t explain to you what they are.”

Engraved coins meant to commemorate events or bestow honors upon a person also fall under the umbrella of love tokens. And sometimes love tokens celebrated not-so-loving phenomena.

The love token with a violin and “EMS,” left, was probably made for a musician, while the love token featuring an anvil and blacksmithing tools was probably made to represent a blacksmith. (Courtesy of the Love Token Society)

“A 20-dollar gold love token says, ‘In Terror of the Tramps,’ and it depicts a little man sitting in a cage that’s in the shape of a chair,” Bastable says. “On the reverse, it honors Sanford Baker, the inventor of this cage known as the ‘tramp chair,’ in Oakland, Maine. If ever a homeless person wandered into this particular town, they were imprisoned in the chair for a day. They were wheeled down to the river, and they were given a bath in the river, and then they were wheeled around town to the jeers from people who were probably throwing rotten vegetables at them. As soon as they got out of the chair at sundown, which is when they were released, they ran for the border and told everyone they could to never go into Oakland.

“If she accepted his love token and wore it, they were engaged.”

“One of our Love Token Society members who’s now deceased had owned that coin,” she continues. “He willed it to one of his sons, who is also a collector of hobo nickels. And we could research the history of the tramp chair, too, which is a rarer thing with love tokens. A lot of them are so generic that you can’t find out who owned them or why. It’s pretty special when you find one that a family passed down or has a name or a story that you can actually research.”

At the Columbian Exposition of 1893 in Chicago, engravers set up booths all around the world’s fair to make attendees love tokens on the spot. That seemed to be the saturation point for love tokens, and soon after, the fad started to die out. Bastable, Gale, and other members of the Love Token Society have speculated as to what brought down the trend.

This love token “spinner pin,” made from a half dollar, could be worn with either side facing outward. (Courtesy of the Love Token Society)

“For one, silver lodes were found,” Bastable says. “Silver became unpopular with the wealthy and was viewed as déclassé. The value of silver, I suppose compared to gold, had decreased, or maybe the rich saw more lower and middle-class people wearing silver or silver-looking things. So gold became the popular metal to wear.”

“Love tokens can’t talk, so they can’t explain to you what they are.”

“Also, if you look at antique jewelry books, you’ll see that 1900 was the heyday for lockets, many of which were made of gold or gold shell and have beautiful repoussé designs or are set with stones,” she continues.

“By then, photography had become more commercial. Paper photographs were more available and affordable, so it’s clear the trend in sentimental jewelry switched to lockets.” Sometimes love tokens were even made into lockets, but those are extraordinarily rare.

Love tokens did have two moments in the 20th century, during the World Wars, when servicemen overseas were making trench art. “Again, these tokens were mementoes, made for similar reasons that the original love tokens were made,” Bastable says. “During World War I, mainly the men had foreign coins engraved to remember where they were stationed, up to four different places. These love tokens usually also have the man’s name and his unit number.”

This watch chain is attached to a love-token dog tag on an 1867 French 2 Franc. It reads, “919643, C.T. Stevens, 102nd F.A., D,” and F.A. stands for “Field Artillery.” (Courtesy of the Love Token Society)

Starting around the first World War, Art Deco “Machine Age” jewelry that looked like metal assembly-line equipment came into vogue. As World War I served as a stark reminder of mortality, women took to wearing sentimental jewelry again, known generally as “sweetheart jewelry.” But instead of love-token bracelets, they favored mass-produced bracelets with rectangular Machine Age links called “forget-me-not bracelets.” Each rectangle could be engraved or struck with a name. And these bracelets remained popular through the 1930s and ’40s.

This transitional Machine Age forget-me-not bracelet has round disks that resemble love tokens. (Courtesy of the Love Toke Society)

When the United States entered World War II in 1941, a patriotic fervor swept across the country, and sweetheart jewelry exploded. Within a few short years, nearly every woman had someone—a son, a brother, a boyfriend, or a husband—serving in the war effort. In particular, the women with loved ones overseas would proudly wear heart-shaped pins and pendants with images of stars and stripes, bald eagles, shields, fighter planes, and military insignia. Love tokens were just one small part of this broader trend.

“In World War II, you might have a few that were engraved with serial numbers or service numbers of the men on love tokens, but more often, love tokens were made into jewelry and sent home to women—their mothers, their girlfriends, their sisters,” Bastable says.

During WWII, U.S. soldiers in the Pacific Theater were paid in Australian coins, some of which they would turn into romantic jewelry, like this bracelet. (Courtesy of the Love Token Society)

Most of the World War II love tokens came from the Pacific Theater and were engraved on Australian coins, which were used to pay U.S. servicemen. Known as “Pacific War Art,” these love tokens might be linked into bracelets or cut into hearts and embedded into heart-shaped pendants of Lucite from the windows or canopies of downed airplanes. After the war, love tokens fell out of favor once more.

This WWII Lucite-and-love-token pendant says “New Guinea” and “To My Darling Sweetheart 1945.” (Courtesy of the Love Token Society)

In 1951, Congress passed U.S. Code 18, which states: “Whoever fraudulently alters, defaces, mutilates, impairs, diminishes, falsifies, scales, or lightens any of the coins coined at the mints of the United States, or any foreign coins which are by law made current or are in actual use or circulation as money within the United States; or Whoever fraudulently possesses, passes, utters, publishes, or sells, or attempts to pass, utter, publish, or sell, or brings into the United States, any such coin, knowing the same to be altered, defaced, mutilated, impaired, diminished, falsified, scaled, or lightened—Shall be fined under this title or imprisoned not more than five years, or both.”

“This law about mutilating coins seemed to make engraving coins illegal,” Bastable says. “But when you read the law, it actually says it’s illegal to ‘fraudulently’ alter the coins and fraudulently altering the coins would be changing a denomination or changing a coin to a rare. Engraving a love token on a coin is not fraudulent. Once they are engraved, they wouldn’t be accepted by merchants or by the government for payment of debts. But the U.S. government threw around some heft and scared off a lot of people from the hobby. Still, the love-token fad had already died out.”

The idea that Code 18 was the downfall of love tokens is hooey, says Gale. “The fads changed,” he says. “In every generation, the granddaughters don’t care what Grandma wore; they want what’s new. I’ve given my granddaughter love tokens, and she couldn’t care less. She just wants jewelry from such-and-such a jewelry store.”

A WWII sweetheart charm bracelet with a “V for Victory” love-token made from a penny. (Courtesy of the Love Token Society)

During the ’50s, charm bracelets took over as the sentimental jewelry du jour. Women and girls would be given charms to honor milestones such as birthdays and anniversaries, or they would buy charms as souvenirs of trips. Mothers often had a charm for each or their children. Some even bought flat charms shaped like silhouettes representing boys and girls, and had each engraved with one of their children’s names.

Love tokens, meanwhile, faded into obscurity for nearly 70 years. Another genre of antique altered coins, hobo nickels, started getting attention in 1982, when Del Romines published a book on their history. Hobo nickels—which, unlike love tokens, were sculpted to alter the coin’s original image—were made and traded by hobos in early 20th-century America. In the early ’80s, so called “neo-bos” started whipping out quick modern hobo nickels. But later in the decade, a serious artist named Ron Landis took coin carving to the next level, making laborious, intricate hobo-nickel designs using a microscope and pins and needles. Some of his pieces have sold for $10,000.

A modern-day hobo nickel by Ron Landis. (Courtesy of the Love Token Society)

In the 2010s, an engraver named Andy Gonzales, who is a follower of Landis’ fine-art hobo-nickel movement, turned his attention to making gorgeous, detailed love tokens. “He started a whole new fad of modern love tokens,” Bastable says. “A lot of the other hobo-nickel carvers have followed suit and made some modern love tokens, too.”

It’s not difficult at all to tell the difference between modern and Victorian love tokens, Bastable says—they use different coins and engraving styles. (Sadly, Gonzales and his wife are currently battling Lyme’s disease, and many people in the coin world have been holding fundraisers for them.)

Even today, love tokens are a niche genre and not the currency of romance. Both Gale and Bastable believe that’s because people are far less sentimental.

Current-day artist Andy Gonzales engraved this “My Beloved” design on a 1900 Liberty nickel. (Courtesy of the Love Token Society)

“People want designer gifts today, whether they like the brands themselves or because it’s a status symbol to impress other people,” Bastable says. “I see a lot more of that commercialization. In the past, estates used to be divvied up, and your family’s things were saved and kept by the survivors. Now when someone passes away, most of what they owned is sold for money.”

“You have to have a sentimental side to be involved in all this,” Gale says. “I’ve showed them to a lot of people, and their eyes just glazed over, bored to death, because they couldn’t care less.”

Indeed, it is a cynical world we live in—today, it would be a rare sight to see a woman on the seashore, clutching an engraved coin, wondering when her love is coming home.

But love tokens give people an opportunity to bring back the romance. “Love tokens were handled, so they’ve got the patina of layers of time and love and emotion,” Rosin says. “I sometimes wear a love token around my neck. For 30 years, I wore it every day. I feel that it brought me blessings: I have a wonderful husband, children, and grandchildren. I’m keeping the love alive.”

This Victorian love token on a 10-dollar gold coin features a moon and star design with blue enamel and a jewel. (Courtesy of the Love Token Society)

(To see more images and learn more about love tokens, visit the Love Token Society’s web site. To learn more about valentines and other “tokens of love,” visit the National Valentine Collectors Association’s web site. To learn more about hobo nickels, as well as the work of Ron Landis and Andy Gonzales, visit the Original Hobo Nickel Society’s web site. To donate to the Gonzaleses’ health fund, go here.)

From Whale Jaws to Corsets: How Sailors' Love Tokens Got Into Women's Underwear

From Whale Jaws to Corsets: How Sailors' Love Tokens Got Into Women's Underwear

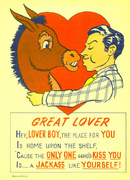

Happy Valentine's Day, I Hate You

Happy Valentine's Day, I Hate You From Whale Jaws to Corsets: How Sailors' Love Tokens Got Into Women's Underwear

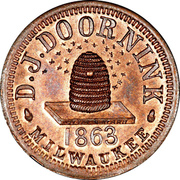

From Whale Jaws to Corsets: How Sailors' Love Tokens Got Into Women's Underwear During the Civil War, Some People Got Rich Quick By Minting Their Own Money

During the Civil War, Some People Got Rich Quick By Minting Their Own Money Sweetheart JewelryMany of the U.S. servicemen who crossed the Atlantic to fight in World War …

Sweetheart JewelryMany of the U.S. servicemen who crossed the Atlantic to fight in World War … Victorian and Edwardian JewelryThe Victorian Era spanned Queen Victoria's rule of England from 1837 until …

Victorian and Edwardian JewelryThe Victorian Era spanned Queen Victoria's rule of England from 1837 until … Love TokensLove tokens, as opposed to the more general term, “tokens of love,” are lit…

Love TokensLove tokens, as opposed to the more general term, “tokens of love,” are lit… Victorian EraThe Victorian Era, named after the prosperous and peaceful reign of England…

Victorian EraThe Victorian Era, named after the prosperous and peaceful reign of England… Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Great article! But I was surprised to read about British convicts being “shipped off to penal colonies in Australia and New Zealand.” New Zealand was certainly a British colony, but never a penal colony. Or if it was, we never learnt about it history class! Thanks, fixed! -Eds

Really a great article! Surprising how many people never heard of love tokens.

Regarding the relationships engraved on love tokens eg Mother, Sister etc, you mentioned ‘Nanny’ and in working-class Britain, ‘Nanny’ was another name for a grandmother, and not an woman employed to look after small children. My nephews’ two grandmothers were called Nanny Glo and Nanny Jean respectively, so everyone knew who was being referred to. Worked for us!

It was great reading the love token article. I wear a gold bracelet loaded with gold love tokens and gold lockets and through the years I have managed to find these stunning pieces with all of my relatives initials. I always get compliments on it and will proudly pass it on to my children. I just hope they will treasure it as much as I do!

Love your love tokens even if I have $20,000.00 of love tokens. I found one $5 gold love token 1868 and the history of the iron factory near Harisburg Pa.

Years ago I found one of these while gardening. I was always wondered why it was a ‘dime’ on one side, when very obviously it was some sort of memento regarding someone’s “Mama”. I had no idea of the tradition of these love tokens. Great article.

Lovely jewelry designs. For Victorian Jewelry online shopping Read customer reviews, they have a lot to tell about the quality of product. Plus you will find out if the website has forged the review and it is actually hustling the customers.

Fantastic article! Many of these love tokens were in my collection and I am so very happy to see them pictured for people to see. Each is a little “work of art”. Thank you.

How would I find love tokens like the ones shown in the article?

In Bath England in 1994 at the Saturday antique market I purchase a thin bangle with five love tokens. The person mentioned it was sometimes referred to as a “ thread et” or “ thretney” referring in some way to a half penny or small change. Are you familiar with this term? Thank you!