One morning, a Mennonite farmer in the Cayo district of western Belize got up like he always did to feed his chickens and milk his cows. Later in the day, like the unmechanized Maya who lived here some 1,200 years ago, he worked up a pretty good sweat tending his winter crops. At the end of his hard day’s work, he headed in for dinner before shuffling off to bed, where he was quickly transported to Mennonite dreamland.

“You have to look at whether there was a trade network, essentially a human-trafficking network, in children.”

Sometime before midnight, the farmer was roused from his slumber by a commotion outside. It seems a Maya-antiquities looter had tumbled into an unexplored cave near his village—the looter’s frightened friend was begging for help. So the farmer and a few of his fellow Mennonites rushed to the scene via horse and buggy, where they lowered the farmer by rope 30 or more feet into the inky darkness. There, he found the unfortunate opportunist, whose numerous injuries included the loss of several teeth, which were dislodged by the impact of his jaw upon the cave’s limestone floor. As he gathered up the bloodied criminal, the farmer noticed human skulls leering in the darkness, skeletal hands groping at the dank air, femurs scattered about. When he finally made it back to the surface and deposited the hapless thief into his buggy before taking him to the nearest hospital, the farmer named this place “Mitnacht Schreknis Heel,” which is Plautdietsch—the Dutch-German dialect of Belizean Mennonites—for “Midnight Terror Cave.”

Top: The entrance to the Midnight Terror Cave. Image via Cal State L.A. Above: Mennonites in Belize, like the one who rescued a looter in the Midnight Terror Cave, still get around by horse and buggy. Image via Balaam Eco Adventures

That was in December of 2006. Meanwhile, more than 2,000 miles to the northwest, Dr. James Brady, a professor of anthropology at California State University, Los Angeles, was doing what he always does—studying Maya cave sites. Brady has been researching Maya caves for more than three decades, pioneering the little-known field of Mesoamerican cave archaeology. He knows as much about Maya caves from the Classic Period (roughly 250 to 900 AD) as it’s possible to know—from the rituals that were conducted in them, including human sacrifices, to the ways in which natural caves were altered to create wide, level plazas where people could congregate in the gloom. Which is why in the spring of 2007, when his colleague Dr. Jaime Awe, then the director of the Institute of Archaeology in Belize, told him about a new Maya cave and invited him to research and study the site, Brady leaped like a looter at the chance.

“I had no idea we were going to run into such an enormous quantity of human bones,” Brady told me recently, referring to the remains from those aforementioned human sacrifices. Coming from a guy who’s seen a lot of bones in a lot of Maya caves, that’s saying something. “When I started out in 1981, most people thought the caves were used for habitation,” he adds. “I threw out the possibility of ritual, but no one knew. Even though I’ve been at this for 30 years, this branch of archaeology is still rather new.”

Skulls on the floor of the Midnight Terror Cave. Image via Cal State L.A.

Significantly, Brady, his colleagues, and the Cal State L.A. students who helped him investigate the site also found a lot of teeth amid the 10,000 bones and 29,000 pottery sherds they cataloged from 2008 through 2010. Being thorough scientists, they also located the injured looter’s teeth, but they were more interested in the 100-plus ancient molars, bicuspids, canines, and incisors they discovered. Of these, many showed little evidence of use, a good indication they came from the skulls of children.

“We encounter bones frequently in caves,” Brady continues. “But the issues that haven’t been resolved are: who were these people and how did they get there.”

Until now: In just the past few months, Brady and his team may have received an answer to a third question—where did the people whose flesh once encased all those bones come from, which may eventually help answer the other two—thanks to the work of Dr. Naomi Marks, who’s a scientist at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in northern California, and just so happens to be my sister (Naomi has come to my editorial rescue before). At the request of one of Brady’s students, Samantha Lorenz, who’s writing her master’s thesis on the teeth, Naomi tested a number of teeth from the Midnight Terror Cave for their strontium isotopic signature, a common practice used to geolocate formerly living “humans” before they became “remains.”

Dr. James Brady, who teaches at Cal State L.A., has been exploring and studying Mesoamerican caves for more than three decades.

Though the data is still being crunched (the full report will be published when Lorenz presents her thesis later this year), initial analysis indicates that the children whose bones littered the Midnight Terror Cave did not come from the surrounding Upper Roaring River Valley, where the cave is located, or even from Belize. In fact, the young victims appear to have been brought to this spot from as far as 200 miles away (an enormous distance in the 9th century), before being taken deep into the earth to have their beating hearts cut from their chests to appease any number of angry gods.

Before you say, “Hey, I saw that movie!” (“Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom” has a similar plot), this is the work of scientific fact rather than Hollywood fiction. And unlike a sensationalist blockbuster, the story behind the Midnight Terror Cave is grounded in years of painstaking research, from high-tech bio-archaeology techniques like checking the strontium isotopes in teeth, to traditional anthropology, which in this case includes studying the ceremonies and practices of the present-day inhabitants of what’s known as the Central Maya Lowlands in order to learn how their ancestors may have lived and died.

Though a controversial practice in some circles, observing the contemporary Maya to glean clues about the lives of their ancient forebears has been an important part of Brady and Awe’s work. For the Maya never completely died out. To be sure, their temples and cities of the Classic Period, some of which had populations of 50,000 to 100,000, were abandoned, and their polities collapsed. But the people themselves lived on, despite the diseases that were brought to their lands by their European conquerors, to say nothing of the conquest itself.

Contemporary Maya still conduct rituals in caves in Mesoamerica, as seen in this still from the documentary “Heart of Sky, Heart of Earth.”

“One of the centerpieces of my studies,” Brady says, “is talking to the living Maya, which I can use as a guide for what life was probably like back then.”

“Those of us who do research in the Maya area,” says Jaime Awe, who now teaches anthropology at Northern Arizona University, “have the advantage of meeting the descendants of the people who utilized these places, be they cave sites or surface sites. They still live in and around some of the ancient Mayan cities, and many of their traditions have continued. By talking with contemporary Maya about their contemporary rituals, we can extrapolate into the past.”

That includes what happened in caves such as Midnight Terror. “The Maya no longer sacrifice people in caves; it’s against the law,” Awe dryly notes, “but I have observed the sacrifice of chickens, sometimes even turkeys. So we can still witness rituals within the cave context, although the practices have changed.”

The ladders used to get researchers into the Midnight Terror Cave (left) are reminiscent of the stairway drawn by architect and artist Frederick Catherwood (right), whose “Incidents of Travel in Central America, Chiapas and Yucatán,” published in 1841, re-introduced Mesoamerica to the Western World.

On a purely intuitive level, that sort of extrapolation sounds right, but for Dr. James Doyle, who’s an assistant curator in the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Department of the Arts of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas, there’s a better reason to reach out to contemporary Maya. “Engaging with contemporary Maya speakers in Mexico, Guatemala, and Belize is important for archaeologists and art historians because the contemporary Maya are obviously very important stakeholders in the interpretation of their past. It’s just best practices when you are working in these countries, especially if you are a foreigner. But it’s problematic to interpret ancient data by looking at contemporary practices,” he says.

Experts agree, however, on the principle of reciprocity. According to Awe, sacrifices and offerings, then as now, are based on a belief in this idea, which he describes as “sympathetic magic.” “If you feed the gods corn tamales and corn tortillas,” he says, “then the gods will reciprocate and provide you with corn by making your crops grow. Many of the rituals in caves had to do with agricultural fertility. In some caves, we can still find the plants and food that were taken into these caves as offerings—corncobs, cacao, annatto seeds.”

This deposit of human remains in Midnight Terror Cave is located in a low muddy area called Bone Soup. Image via Cal State L.A.

Okay, reciprocity, I think can get my head around the logic of that, even if I don’t happen to believe in it. But why spill the blood of humans—and children, no less? “The ancient Maya and even the recorded Maya (the Colonial Spanish priests reported this) believed humans were made from corn,” says Awe. “And so, when you offered a human, you were essentially feeding corn to the gods.” Since maize was the most important staple of the Maya, human sacrifice was not seen as taking the principle of reciprocity too far. Indeed, it may well have been viewed as the least a grateful populace could do to ensure its survival.

“The life cycle was very important to the Classic Maya,” agrees Doyle, “and it all, I think, goes back to the concept that people are made from maize. For example, the title ‘Ch’ok’ is used for royal Mayan youths, but in the Colonial-era dictionary, it’s also used as the word for maize sprout, the beginning of the maize plant. So there’s clearly an association of life cycles with agricultural cycles. Not only was agricultural fertility very important for the Maya’s day-to-day subsistence, but it was also part of the creation of the Maya people.”

Naturally, two of the most frequently beseeched gods were the god of maize, who does not have a formal name as far as anthropologists can tell, and the god of rain, whose name is variously spelled “Chac,” “Chaak,” or “Chahk.” “The Maya hieroglyph decipherment folks are very much involved in these debates of pronunciation,” Doyle says. “But we can’t know exactly for sure how the ancient Maya would have said it. Would they have said ‘Cha-ak’ with a long ‘a’ or ‘Chahk’ with a glottal ‘h.’ It depends on who you talk to.”

This small ceramic vessel from 7th-8th century Guatemala depicts Chaak, god of rain. Via the Metropolitan Museum of Art

The reason for Chaak’s popularity (we’ll use Brady’s preferred spelling) relates directly to the abandonment of caves such as Midnight Terror by the Maya sometime in the 9th century, as well as the proliferation children’s bones within. According to a paper by B.L. Turner and Jeremy Sabloff in the August 2012 issue of the “Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences,” the Terminal Classic Period of the Maya, roughly 800-1000 AD, saw eight droughts lasting 3-18 years long.

No doubt the lack of rainfall during that period increased the number of times local Maya would have gone to the Midnight Terror Cave to offer Chaak food, material goods such as pottery, and human blood. And since, according to Jim Brady, children were the sacrifice victims of choice when calling on the rain god, the droughts probably help account for the large quantities of children’s bones in Midnight Terror.

It would be convenient to view the climate change that helped upend Maya society at the end of the Classic Period as an event beyond the Maya’s—and Chaak’s—control. But Turner and Sabloff argue that it wasn’t just drought that undid the 9th-century inhabitants of the Central Maya Lowlands. The overall reduction in rainfall during the period, they point out, was only 40 percent of normal, or less. In fact, the farming practices of the Classic Period Maya’s ancestors may have been the real reason why so many Maya children were sacrificed.

A student from Cal State L.A. crouches on a man-made retaining wall built inside the Midnight Terror Cave. Image via Cal State L.A.

“There’s evidence to show that the farming practices of the Preclassic Period were perhaps even more deleterious than the ones of the Classic Period, when the Maya were managing water resources with terracing, reservoirs, and these type of things,” says Doyle. “From about 300 BC to 100 AD, we see a build up of what’s called Maya clay, an anthropogenic [caused by humans] soil that is basically runoff as a result of deforestation. And so, during the late Preclassic Period, which is a peak of population in the Maya Lowlands before the Classic period, you have some farming practices that perhaps contributed to the need for better water management via reservoirs, canals, and the things you see in Classic Period agriculture.”

The paleontological data support this view. They reveal steep drops in forest pollen (losses of up to 90 percent), which is evidence of large-scale deforestation, presumably for fuel and farmland. Forests hold more soil moisture than open land, which means less moisture is released into the atmosphere to fall locally as precipitation. Combined with the common practice of slashing-and-burning, which promoted the proliferation of an invasive species of bracken fern, and you get a picture of an infertile landscape, “millennia in the making,” as Turner and Sabloff put it, ill-suited for even a 40 percent overall rainfall reduction. We’ll probably never know if there was an ancient-Maya equivalent of Al Gore running around, warning of the harm that the Maya were doing to their Mesoamerican environment. What we do know is that a lot of caves in that part of the world are filled with a lot of bones.

Like the Midnight Terror Cave, the temple of Xunantunich is located in the Cayo District of Belize. The temple was built when the cave was in active use. Image via Wikipedia

By now, you may be wondering what role the famous stepped Mayan temples at Tikal, Palenque, Chichen Itza, and other sites might have played in the Maya’s quest for rain. Wasn’t that what the temples were for? Weren’t they essentially ladders to the heavens, platforms to permit the local shamans to mount their steps so they could make their public offerings of maize (be they corn cobs or human beings) that much closer to the gods?

“If you’re sacrificing people on a large scale and you’re only drawing from within your own society, that could cause some real social unrest.”

In fact, in Mayan cosmology, caves are every bit as important as temples, if not more so. “Many aboveground Mayan sites are located directly over caves,” explains Awe. Although Awe stops short of claiming that all Mayan temples are paired with caves (scientists have not actually looked under every single temple to verify that this is true, he points out), he acknowledges the relationship between the two. “In some cases, some Maya even went so far as to construct caves beneath some of their sites,” he says of those aboveground sites that lacked natural forms below. “And we know there’s a strong ideological connection for the Maya between the underworld/Earth and the heavens. It creates the perfect ancient-Maya cosmology of the universe.”

Like the cosmology that was prevalent in the Christian world prior to Galileo’s heliocentric heresies of the early 17th century, the Maya believed the Earth was the center of the universe. Such cosmologies are usually described as geocentric—in a heliocentric cosmology, the Earth revolves around the sun. Throughout ancient and recorded history, many of the world’s greatest civilizations were geocentric, too, so the ancient Maya were not unusual in this respect. But the Maya went several steps further, believing the Earth was something of a deity, and that caves were the sources of everything from life-giving rain to death-spreading disease. The Earth giveth, the Earth taketh away, and it was only by entering into the Earth—to let its very breath fill one’s lungs—that one could commune with the gods who did their business there. Chaak was one of the most important gods the Maya summoned in caves because without rainfall, how are people to live?

One of numerous skulls found in the Midnight Terror Cave. Image via Cal State L.A.

Or, in the case of all those children in the Midnight Terror Cave, to die. And that’s definitely one reason why the scientists are here—to unravel the bloody mysteries of this ancient place. But the bones in the Midnight Terror Cave, as well as the colorful name of the cave itself, have lured intellectual looters, too, who descended on the place in search of scandal almost before the injuries of the original looter, who brought the site to the archaeological world’s attention, had healed.

The first scandal-hunters arrived at Jaime Awe’s doorstep in 2007 in the form of a television crew for the Discovery Channel. Seduced, perhaps, by the network’s veneer of respectability, Awe gave them permission to shoot an episode for a short-lived “reality” show called “Bone Detectives.” The episode eventually aired on January 21, 2008, as “Cave of the Headless Corpse,” and it was breathlessly described as follows:

“Scotty travels to Belize where a cave has been discovered deep in the jungle containing thousands of human bones. As Scotty ventures down more than ten stories into the cave, he discovers a skeleton in a hidden chamber — but the head is missing! Scotty embarks on a search for the missing skull. If he can find the skull, he might be able to identify this victim, and solve the mystery of the cave known as ‘Midnight Terror.’ Was this man buried in the cave to honor his life? Or was he the victim of a violent ritual sacrifice deep inside the ancient Mayan underworld?”

Scott Moore was the host of the Discovery Channel’s short-lived “reality” show called “Bone Detectives.”

“I learned a good lesson from that experience,” Awe says now with a sigh. “These guys were trying to force the information we were getting to fit the storyline they had in mind. They would ask a question like, ‘Do you think that this skull belongs to that skeleton?’ And I would answer, ‘Well, you know, it’s possible that this skull belongs to that skeleton, however, the information we’ve gathered strongly suggests otherwise.’ Well, they would just keep the part that said ‘it’s possible that this skull belongs to that skeleton.’ It was that kind of crap that made me lose all respect for them—they were misrepresenting the data. I remember writing to the producer, saying, you should probably call your program ‘Bonehead Detectives.’”

To make matters worse, Awe says, the show shined an unwelcome spotlight on the then-little-known site, luring even more antiquities thieves to the remote area. “By the time Jim had started his work at the site in the spring of 2008,” Awe says, “we were seeing increased activity in the area by looters.”

Still, enough was left undisturbed to keep Brady and his teams busy for several years. Which brings us back to the teeth, Samantha Lorenz’s master’s thesis, and my sister, who tested one of the teeth for its strontium isotopic signature when I visited her recently.

A Mass Spectrometer like this one can be used to calculate the isotopic ratio of strontium in a human tooth. The sandwich-like object at center-left is the magnet that causes the different strontium isotopes to separate. Image via ThermoScientific

By then, Lorenz had already delivered a handful of human molars, plus one tooth from a cave rodent as a control, to Naomi. “She was funny when I showed up with all these vials of teeth in them,” remembers Lorenz. “I think it creeped her out a little bit.” I confess that I was less creeped out, and even recall being a bit giddy as I excitedly asked my sister if we’d get to choose the tooth she’d be testing that day. Her response was the sort of look that all big brothers experience when they have much smarter younger sisters. “The teeth are no longer teeth,” she explained, like she was talking to a 4-year-old. “Samantha has already ground them up.”

Crestfallen, I followed her into a lab, where she ran one of the teeth, or what was left of it, through a mass spectrometer to gauge its strontium isotopic signature.

Strontium (Sr) is number 38 in the periodic table of elements, making it a good deal heavier than carbon (number 8) and a whole lot lighter than lead (number 82). Like calcium, strontium builds up in our bones and teeth via the consumption of food and water. Once our first permanent molars come in, the strontium content in a tooth’s enamel is fixed, which is why first molars are the teeth of choice for scientists like Lorenz. Like a lot of other elements, strontium has a number of stable isotopes, which are basically variations of a main element, except with more neutrons than protons. So it’s not just strontium that accumulates in the enamel of our teeth but trace amounts of each of its four stable isotopes.

Samples are affixed to rhenium filaments, which are loaded onto wheels, or turrets, inside the TIMS. Image via ThermoScientific

For those of us who live in the developed world and drink bottled water and eat imported foods, strontium testing won’t tell a scientist much since the strontium that has lodged in the enamel of our teeth while they were forming is from all over the planet. But for populations that rarely traveled far from where they were born, like the Maya of Mesoamerica, strontium testing can pinpoint, with surprising accuracy, where a person grew up.

As it turns out, the amounts of 84Sr, 86Sr, 87Sr, and 88Sr, the element’s four stable isotopes, vary from place to place, except near any ocean, where the ratios between the amounts of those four strontium isotopes are exactly the same, whether you live in a fishing village in Polynesia or Alaska. But go a few miles inland, and those ratios act like geolocation pins on a Google map.

The ground up rodent tooth will tell Naomi what the ratios are in the Midnight Terror Cave, since it’s a reasonable assumption that the rodent had only consumed food and water from the area in and around the cave. If the ratios for the other teeth are not the same, Lorenz will know that those teeth, and hence the children who were sacrificed to Chaak, came from somewhere else. Lorenz will not have to capture rodents from across Mesoamerica to figure out where—that work has already been completed by David Hodell and a few other colleagues, although instead of using rodent teeth, they mapped the strontium ratios of water, rock, soil, and plants throughout the Central Maya Lowlands and up into the Yucatan Peninsula for precisely this purpose.

The lab that Brady and his students form Cal State L.A. used in Belize. Image via Cal State L.A.

Turning teeth into samples takes several days, not counting all the time it takes to find the teeth, catalog them, and then choose the ones you are going to grind into powder in the name of science. “For the purposes of the strontium testing,” Lorenz says, “I pulled any of the first lower molars we had that were in a good enough condition where I would be able to make molds of them so they could still be studied later. The first molar that comes in, the first permanent molar that erupts, happens around 6 years of age.” All of the samples that were eventually tested are believed to have come from children estimated to be between the ages of 6 and 14.

After the teeth have been ground into a fine powder, they are dissolved in nitric acid. It takes another day or so to remove as much non-strontium elements, particularly rubidium, which is very close in its molecular structure and weight to strontium, as you can. Once the samples are purified, someone (Naomi) has to place a drop of each sample onto a short, slender, and fragile rhenium filament with a micropipetter (basically, an eyedropper), after which the filaments are briefly heated to about 700 degrees centigrade to bind the sample to the rhenium. Then, the better part of another day is spent loading the filaments onto the wheels (called turrets) that will be placed inside a machine called a Thermal Ionization Mass Spectrometer, which Naomi and everyone else at Lawrence Livermore called the TIMS.

Tens of thousands of pottery sherds were recovered from the Midnight Terror Cave before looters could get to them. Image via Cal State L.A.

It all sounds complicated and high tech, and it is, but on another level, the TIMS is a fairly simple machine. It’s basically a vacuum tube that is electrically charged positive at one end and negative at the other. The tube bends at roughly 90 degrees to get from its positive to negative ends, and where it makes that turn, it runs through a huge magnet, about the size of a kitchen sink.

As Naomi slowly increases the current flowing through the rhenium filament, heating it to 1,400 or so degrees Celsius (the machine features a peep hole you can look through to confirm that the filament is glowing red), those four stable strontium isotopes ionize, which is rather like the process of water evaporating into a gas. In the case of the strontium, the solid material on the hot filament ionizes, sending ions from the various strontium isotopes that were present in one of the Maya sacrifice victim’s teeth into the vacuum. Because the filament is positively charged at this end, and because there is a negatively charged element at the vacuum tube’s other end, the ions immediately head toward the negatively charged end, coalescing into a single stream. But before they get there, though, they must make a sharp right-hand turn through that kitchen-sink-size magnet.

Some of those pottery sherds were put together, like pieces of an enormous jigsaw puzzle, to restore Mayan vessels to a semblance of their former beauty. Image via Cal State L.A.

Here’s the part I find amazing, both for its simplicity and elegance: As the stream makes the turn, the different masses of the ions, small though they may be, suddenly become relevant, with the lighter ones hugging the inside of the curve and the heavier ones thrown to the outside, just like on a playground merry-go-round. By the time the ions straighten out, there are now four streams heading toward the negatively charged end of the vacuum tube, where each stream is collected in what are called Faraday cups or buckets, which are made out of graphite and named for the eminent 19th-century English electrochemist, although, Naomi tells me, they do not actually resemble cups or buckets. I’ll take her word for it that the cups, whatever they look like, are somehow equipped to capture the ions from the different strontium isotopes, which allows a computer program that Naomi monitors and fiddles with while the sample is running to calculate the ratio of each isotope to the other, all in real time. This is how Naomi calculates the strontium isotopic ratio in a particular tooth, which Lorenz can check against David Hodell’s strontium-ratio maps to learn the geolocation of the food and water consumed by the sacrifice victim as a child.

As Lorenz would learn when she did exactly that, the children who were sacrificed in the Midnight Terror Cave grew up hundreds of miles away. “No one’s from Belize,” says Lorenz, “so that means we have this population of children that was brought in from somewhere else for the purpose of sacrifice. Were these children taken? Were they sold? Were they voluntarily given up? Were they orphans? There are a lot of different things we need to look into. And because there are so many of them all coming from the same region, then you have to look at whether there was a trade network, essentially a human-trafficking network, in children.”

James Doyle, however, isn’t so sure. “Without having seen the published results of the strontium study, I can’t say too much,” he says. “However, I would very much hesitate to apply modern terms, such as ‘human trafficking,’ to these ancient rituals; it is a vastly different context and we can only hazard a guess as to the motivations for ancient peoples moving on the landscape. From my understanding, if they found strontium isotopes that differed from that of the region near the cave, it would only imply that the children were born and grew up elsewhere, and they very much could have migrated to the area before their remains ended up in the cave. Without knowing the bioanthropology study (e.g., finding cut marks, evidence of bound limbs, other pathologies), we also can’t say that the children didn’t die of natural causes. There surely would have been high infant-mortality rates in these pre-industrial communities.”

More bones in the Midnight Terror Cave. Image via Cal State L.A.

“Various ethno-historic information from the Spanish suggests that if children were orphaned or something like that, the kids were snatched up immediately and used as sacrificial victims,” Brady says. “So we know that sacrifice victims also came from within a society. But if you’re sacrificing people on a large scale and you’re only drawing from within your own society, that could cause some real social unrest, which is why capturing warriors or importing victims from another kingdom probably came to be preferred. But we have no hard data on this yet for the entire Maya area.”

That may change as more teeth like the ones from the Midnight Terror Cave are tested for their strontium isotopic signatures. If those teeth are any indication of data to come, scientists and the general public may not like what they learn.

“Anything dealing with the sacrifice of children is going to be difficult to look at,” says Lorenz. “But it definitely piques my interest in the Maya culture, and makes me want to understand what would have been happening at that time to support a worldview in which children could be basically taken from their homes and sacrificed for what I would imagine was a belief in a greater good.”

The looter who fell into the Midnight Terror Cave lost three teeth when his jaw hit the cave’s limestone floor. Brady and his team found them.

Today, the practices of the ancient Maya in caves like Midnight Terror feel distant and abstract, as divorced from our everyday reality as that “Indiana Jones” movie or the behavior of the boneheads from the Discovery Channel. In fact, the contemporary Maya appear to be equally comfortable with a certain amount of abstraction, as seen in their casual substitution today of chicken blood for human blood, the precedent for which can be easily found throughout present-day Mesoamerica. “Obviously chickens are not thought to be made from corn when they are offered as a sacrifice,” says Awe, “but it’s just like when you go into a Catholic church and they say ‘Here’s the blood of Christ’ before you drink some wine. What’s important is the symbolic offering.”

Even so, for a young scientist like Lorenz, maintaining a sense of academic reserve is not always easy. “I guess in some ways it doesn’t feel that far off to me,” she admits. “I worked in a Maya community in Guatemala a couple of summers ago. We were excavating mass-grave sites from the recent internal armed conflict, and near where we were working, there were all these children running around. Sometimes I picture those children when I think about who’s in that cave.”

Why the 'Native' Fashion Trend Is Pissing Off Real Native Americans

Why the 'Native' Fashion Trend Is Pissing Off Real Native Americans

Skeletons in Our Closets: Will the Private Market for Dinosaur Bones Destroy Us All?

Skeletons in Our Closets: Will the Private Market for Dinosaur Bones Destroy Us All? Why the 'Native' Fashion Trend Is Pissing Off Real Native Americans

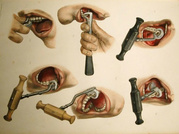

Why the 'Native' Fashion Trend Is Pissing Off Real Native Americans Bloodletting, Bone Brushes, and Tooth Keys: White-Knuckle Adventures in Early Dentistry

Bloodletting, Bone Brushes, and Tooth Keys: White-Knuckle Adventures in Early Dentistry Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

EXCELENTE

I was the host of the Discovery show mentioned in the article. I have to agree that the producers of the show were much more interested in fitting facts to their story (like all TV programs), which was something that frustrated me as well, but I have to disagree with Dr. Awe’s assertion that the show somehow served as a lightning rod to bring looters to the site. There was no detailed information about the location of the site in the show (something I strongly pushed for) and local knowledge of the site in Belize was much more common than he suggests. Protecting resources is an extremely important part of any archaeologist’s job and I take that very seriously.

So w still don’t know if the children were sacrificed “before being taken deep into the earth to have their beating hearts cut from their chests to appease any number of angry gods”. However, the sensationalist cadence of this note tries to push the reader in that direction (not to mention the name “Midnight Terror” cave). The remains could have been deposited in the cave after a natural death; or not. But still, no evidence of either.

Also, mixing the temples at Tikal, Palenque, and Chichén Itzá is just wrong, as only one was habituated during the drought (Chichén 750-1250AD).

Finally, this cave is an isolated context. Not evidence of a common practice among the ancient Mayans.

The teeth of the looter look like they have been pulled out…

How do the researchers know this wasn’t a mass tomb for dead or dying?

Title is misleading. Thouroughly dissapointing considering story mentions complaints at popular program misrepresenting facts. No “ancient child-trafficking ring” can be deduced from this paper. Shame!

I’m seriously questioning the validity to the statements about the alleged Menonnites. Most Menonnites do not speak with “Dutch” dialects, and furthermore the term Dutch when in reference to people of the Annabaptist sect typically refers to German. It’s from an early mispronounciation of Deutsch that created a long misunderstanding. I could be wrong, but he appears to be talking about Amish speaking a variation on German.

At any rate the introduction of Menonnites falling to sleep into “Menonnite dreamland” is silly and unprofessional and somewhat rude to people of that faith.

Why is there no carbon dates on any bones found. Is it because they are close to 14-15oo’s so its evidence of spanish and catholic war crimes of sovereign tribal nations. Probably so. Tultek inik itza