The first time you heard the word “Oneida,” it was probably in the context of silverware. Perhaps it was before a Christmas dinner, when your mom or grandmother instructed you get out the “good silver” made by Oneida Limited. Even though it was only silverplate rather than sterling, your family probably stored it in a velvet-lined wooden case. Or maybe you saw an ad depicting an elegant table set with Oneida flatware while flipping through the pages of “Good Housekeeping” or “Better Homes and Gardens.” You might also have encountered Oneida while watching “The Price Is Right,” enthralled by the model wowing a studio audience when she opened a chest of gleaming Oneida cutlery for the contestants to bid on.

John Humphrey Noyes talks about Jesus being a battery who will charge you with electric life. He believed some ways of communicating this magnetic fluid were more effective, like having sexual intercourse.”

In fact, Oneida is the name of a First Nations tribe that occupied much of upstate New York long before it was called upstate New York. Given those deep roots, along with its later symbolism as the brand of flatware most associated with American middle-class aspirationalism and traditional gender roles, it’s doubly ironic that Oneida Limited actually emerged from a 19th-century polyamorous communist Christian utopia known as the Oneida Community.

Founded in 1848, and in operation for just over three decades, the Oneida Community was profoundly revolutionary for its time, paving the way for advances in women’s and workers’ rights. At the commune headquartered on the Oneida River in upstate New York, women cut their hair short, ditched the corset, and did the same work as the men. Everyone worked four to six hours a day, and no one accumulated any material possessions—not furniture, not fine clothing, and certainly not silverware.

Most scandalously, commune members engaged in a system of “complex marriage,” believing that loving, open sexual relationships could bring them closer to God. They believed the liquid electricity of Jesus Christ’s spirit flowed through words and touch, and that a chain of sexual intercourse would create a spiritual battery so charged with God’s energy that the community would transcend into immortality, creating heaven on earth.

Top: To counter criticism, the Oneida Community put out this photograph, circa 1870, of men and women in the Mansion House public square or “quadrangle.” The women, though still in pants, avert their gazes, and the men have removed their hats according to Victorian bourgeois custom. (Courtesy of Picador) Above: A 55-piece set of Oneida silverplate in the “Plantation” pattern from 1948.

Ellen Wayland-Smith, a descendant of members of the Oneida commune, delves her into family’s history in her new book, Oneida: From Free Love Utopia to the Well-Set Table. Oneida’s early enterprises included canning fruits and vegetables and manufacturing animal traps, chain link, and silk sewing thread. It was Wayland-Smith’s great-great-grandfather, Charles Cragin, who in 1877 suggested the community start making spoons at its colony in Wallingford, Connecticut, near the rushing Quinnipiac River. The original polyamorous religious commune broke up in 1880 and reorganized its assets into a corporation. In the 1890s, Oneida Community, Limited, started to drop its other products to focus on the cutlery market. For roughly 100 years, the silverware corporation—which was eventually renamed Oneida Limited—thrived under the leadership of the Community’s descendants. However, the 2000s weren’t kind to Oneida, so its executives had to file for bankruptcy in 2006 and sell the brand, which is owned by a houseware conglomerate now.

Wayland-Smith’s book begins in July 1948, when Oneida Limited flatware manufacturer celebrated the Community’s 100th birthday and the company’s reputation as—forgive the pun—a “sterling” example of American industry. On a grandstand outside the original community’s 93,000-square foot Victorian brick home called the Mansion House in Oneida, New York, the crowd enjoyed a soprano and organist performing “The Star-Spangled Banner,” the crowning of a “Silver Queen,” and a string of circus and daredevil acts. At the end of the day, attendees danced to the music of Jimmy Dorsey’s orchestra. At the festivities, the company touted its patriotism and contributions to American capitalism, as well as its devotion to social equality and the golden rule. What attendees didn’t know was that a truckload of papers documenting the Oneida Community’s spiritual-sexual experiments had—just a year before—been taken to the Oneida town dump and set on fire.

This 1920s ad for Oneida’s Community Plate brand of silverplate flatware suggests its “Paul Revere” pattern suits every occasion, from formal to informal. Click on the image to see it larger.

“The burning of the papers, which happened in 1947, included original members’ diaries, letters, and the community notes and logs in terms of their sexual practices,” Wayland-Smith explains. “All of these sensitive materials were in that collection. The Oneida descendants knew about the burning, obviously. At the time, they had people knocking at their doors, trying to get access to these papers, and they thought, ‘You know what, we’re going to put an end to this for good.’ In some ways, they were intensely private people.”

Fortunately for Wayland-Smith, previous Oneida chronicler Spencer Klaw, and anyone else who wants to dig into the community’s history, it wasn’t all lost. While the large archive accumulated by Oneida descendant, George Wallingford Noyes, was burned, other family members held onto diaries and letters. Those, along with the myriad publications like books and newspapers the Oneida Community put out into the world, are now housed at the Oneida Community Collection at Syracuse University.

Oneida began—as most utopias do—with the vision of one charismatic leader, in this case, a preacher named John Humphrey Noyes. Born to a well-off family in Putney, Vermont, in 1811, Noyes, an awkward and introverted redhead, grew up lamenting his feelings of sexual frustration. When his religiously devout mother sent him to a tent revival in fall of 1831, the 20-year-old virgin discovered he could channel all his erotic energy into Christianity.

A picture, dated 1851, of John Humphrey Noyes at age 40. (Courtesy of Picador)

At the time, industrialization in the United States was just gearing up, threatening to unravel the fabric of Americans’ agrarian lifestyle as they knew it. Before the 19th century, Americans believed they’d left the ugly, inequitable factory system of England behind. While the South had its large slave plantations, New Englanders, at least, thought freedom meant living in small villages where artisans and farmers owned their own land and thrived on subsistence agriculture. Of course, white men were the only Americans who had full legal rights in the early 19th century, which included the rights to own land and slaves, and these men essentially owned their wives and children as well. According to Wayland-Smith’s Oneida, the dog-eat-dog system of free-market capitalism was not yet a part of the American dream. Wage labor was thought of as akin to slavery, and the notion of an individual pursuing his own wealth and self-interest above that of the community was an appalling, grievous sin.

“At first, the Oneidans had these very sane work hours, four to six hours a day, and their duties were always shifting, balanced between domestic and trade labor.”

Amid this growing sense of social and economic uncertainty, Christian sects sprang up, attracting legions of converts through traveling tent revivals during a time that became known as the Second Great Awakening. Many of these new denominations, such as Methodists and Baptists, rejected the Puritan belief that only God’s chosen could go to heaven; instead they believed that by choosing to follow Christ through human free will, anyone could receive God’s grace and be redeemed from their sinful natures. So-called Perfectionists took that a step further, saying that accepting God’s grace made true believers “perfect” and free from sin.

“It was such a volatile time in American history,” Wayland-Smith says. “The beginnings of the Industrial Revolution were happening in tandem with the market and transportation revolutions. The familiar ways of being—living in small, tight-knit communities in a mostly classless society—were beginning to break apart. People felt very vulnerable and didn’t quite know how to identify themselves. Today, we have this idea we Americans were always these ardent capitalists who were gung-ho about the free market and individualism. But when the market economy first got going, the idea of competition and struggling against your neighbor to make a living horrified Americans. They couldn’t accept that the new model for the economy was going down this path towards ‘selfishness,’ a concept that haunted people. That, to me, is one of the reasons why John Humphrey Noyes, who otherwise had some very strange ideas, attracted followers.”

A 1917 Oneida silverplate ladle in the “Adam” pattern, marked “Community Plate.”

In that moment of upheaval, many of the tent-revival pastors spreading Baptist, Methodist, or Perfectionist ideology asserted Christ’s return was imminent. They adopted a literal reading of the Book of Revelations, which says that Jesus will come back and rule the earth for 1,000 years. To prepare for his arrival, “reform Christians” sought to improve conditions on Earth, eliminating slavery (abolition), providing voting rights for women (the suffrage movement), and preventing women from suffering abuse at the hands of alcoholic husbands (temperance).

“Oneidans never for a minute pretended that women were equal to men. But on the ground, practically, women could do anything that men could do.”

“In Revelations, as it was read, Christ was supposed to return to earth and reign for a thousand years over Earth,” Wayland-Smith says. “Satan would be bound in chains, but after 1,000 years, he would break out and that’s when the Last Judgment would happen, leading to the final reconciliation of heaven and earth. With all the social and economic instability of the 19th century, many Americans felt their world was ending and assumed that the Millennium was just around the corner. John Humphrey Noyes’ commune was one of many sects that predicted how that was going to happen. A lot of 19th-century reform movements were based in religion; the idea was Christ is coming back, and we better get our house in order.”

Traveling tabernacle sermons allowed proper middle-class Americans—who normally kept their emotions buttoned up, according to 19th-century mores—to sob, yell, tremble, moan, and dance. The experience was not dissimilar to sexual release, and the free expression was so novel and liberating that documents show it often led charged-up worshippers to hook up after the revival. While Noyes did not get laid after his first tent revival, he did feel called to join the ministry, and attended seminary at Andover in Newton, Massachusetts, for a year and then at Yale, where he took the concepts of Perfectionism even further: In February 1834, he claimed he had achieved complete holiness on Earth and, therefore, nothing he did would ever be a sin. He also felt liberated from the imperative to follow governmental laws. For his heresy, Yale kicked him out and stripped him of his right to preach. As his friends in New Haven, Connecticut, fell away, Noyes managed to convert one young woman, Abigail Merwin, to his concept of perfect holiness, and she stood by him in the face of public disgrace.

This Community Plate ad by illustrator Coles Phillips appeared in the September 1924 edition of “Ladies Home Journal.” His “pretty girl art” style depicts women with modern flapper fashion and bourgeois aspirations of marriage. Click on the image to see it larger.

Ostracized, Noyes left Merwin in New Haven in May of 1834 for a crime- and disease-ridden neighborhood in Manhattan, where, after hallucinating a passionate encounter with God’s spirit, he imagined he was besieged by the devil. For three weeks, dirty and deprived of sleep and food, he roamed the streets desperately warning of the impending arrival of Christ’s judgment to anyone who’d listen. Although Noyes believed he came out of his trial with the devil triumphant, his family and friends just thought he’d lost his mind. After this brief, wild stint in New York City, he bounced around New England, mostly between New Haven and his family home in Putney, publishing Perfectionist newsletters, trying to repair the sect’s reputation for sexual impropriety.

“The company made its fortune on convincing middle-class housewives that you had to have a fork for every course and special utensils like grapefruit spoons.”

During the fall of 1835, Noyes was devastated to learn that Merwin, whom he saw as his partner in his crusade, was engaged to another man. To comfort himself, he embraced the popular 19th-century concept of “spiritual spouses,” which held that couples married for earthly reasons such as financial stability, but a man or woman’s true soul mate could be someone else entirely and that person would be their husband or wife in heaven, where they would engage in “angel sex.” Noyes wrote Merwin a letter to explain her status as his spiritual wife. Then he followed the couple to Ithaca, New York, where he started a Perfectionist newspaper called “The Witness” and tried to persuade Merwin to rejoin his movement. She wouldn’t even talk to him.

In January 1837, Noyes wrote a letter to a friend, explaining his shift from believing in spiritual wives to spiritual polyamory—which, he insisted, would be enacted on earth once Jesus arrived: “When the will of God is down on earth as it is in heaven there will be no marriage. Exclusiveness, jealousy, quarreling have no place at the marriage supper of the Lamb. I call a certain woman my wife. She is yours, she is Christ’s, and in him she is the bride of all saints. She is now in the hands of a stranger, and according to my promise to her I rejoice. My claim upon her cuts directly across the marriage covenant of this world, and God knows the end.” The letter ended up in the hands of a Philadelphia preacher who published it in his August 1837 newsletter on Christian free love. The ensuing uproar prompted all subscribers to “The Witness” to cancel, leaving Noyes in debt.

During World War II, the Oneida descendants who ran Oneida Limited put out a newsletter called “The Community Commando” about its contributions to the war effort. Click on the image to see it larger. (Via WikiCommons)

“When he was growing up, it seems John Humphrey Noyes had a problem relating to girls,” Wayland-Smith says. “He was painfully shy and couldn’t seem to get over it. When you look at the way in which his theology developed, it tended to evolve in relationship to these personal issues—whatever was obsessing him romantically. In the 1920s, George Wallingford Noyes was going to publish a book about the transition to so-called ‘complex marriage’ and what he called the ‘social’ side of John Humphrey Noyes’ theology. His theory was that complex marriage never would have had come about if it hadn’t been for Abigail Merwin, Noyes’ original convert who rejected him. When the family found out that this was the thesis, they were completely upset and told them under no circumstances could he publish that, because it made a very explicit link between John Humphrey Noyes’ sexuality and his theology.”

“Noyes thought if a woman can’t control her reproduction, she doesn’t have time for anything else. It’s amazing that the Oneidans understood that and gave that freedom to the women.”

Back in the fall of 1837, a Vermont convert, a wealthy young woman named Harriet Holton, sent Noyes’ $80 to pay off his creditors in Ithaca, and the two began corresponding. In June 1838, Noyes asked Holton to marry him—on the condition that they wouldn’t be exclusive “in the free fellowship of God’s universal family.” Quickly, he moved with Holton back to Putney, where he renewed publishing “The Witness” and recruited one of his brothers and two of his sisters (Wayland-Smith’s great-great-great-grandmothers), as well as his sisters’ husbands, to his cause. Two more of Noyes’ converts, George and Mary Cragin (one set of Wayland-Smith’s great-great-great-grandparents), joined his family in Putney in 1841.

With the help of the Noyes’ inheritance from the passing of their father, the group of nine established The Society of Inquiry to “make an open and united confession of this our belief and more effectually assist each other in searching the Scriptures and in overcoming sin.” The members invested a total of $38,000 into the community, which would be worth $1 million in today’s dollars. There, in Putney, Noyes further developed his idea of “Bible Communism,” wherein converts shared everything they possibly could. By March 1843, the Society had 35 recruits.

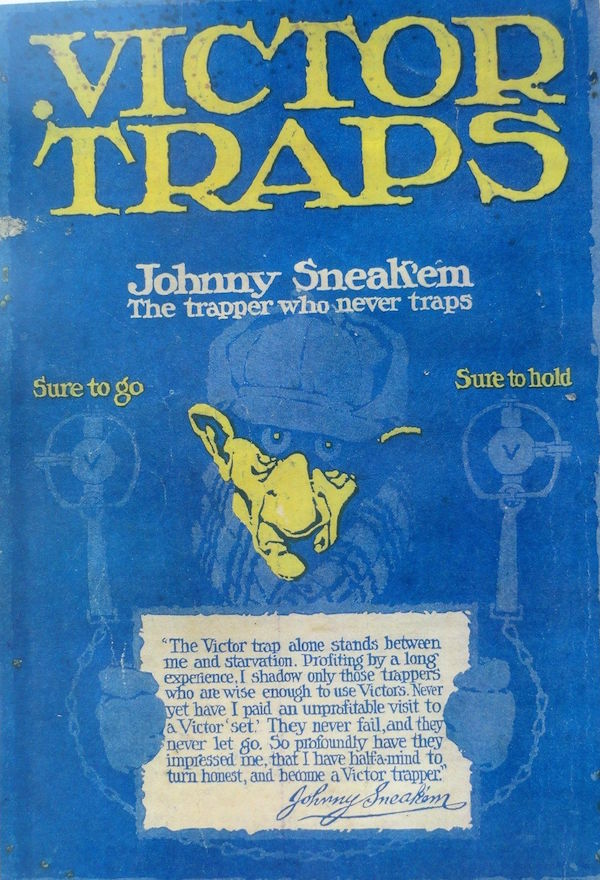

These four rusted vintage Victor Traps were produced by Oneida Community, Limited.

The transition from John Humphrey Noyes’ abstract, theoretical polyamory to actual extramarital sex didn’t take place until 1846, after George Cragin expressed his attraction to Noyes’ wife, Harriet. His affection was returned, and Noyes’ also felt Mary Cragin was his new spiritual wife. The two couples, the Noyes and the Cragins, met and agreed to the Society’s first “complex marriage” engagement, to be acted on when the kingdom of Christ arrived. However, when Noyes, out walking with Mary, felt overwhelmed with passion, he quickly decided that God’s kingdom had already arrived—and that it was starting quietly, stealthily in Putney and would slowly spread throughout the world. It was the Society’s job to create and spread paradise on earth.

“When the Supreme Court decided to outlaw polygamy in Utah, that was the death knell for non-monogamy. Up until that point, it had been up in the air whether polygamy would be tolerated in the U.S.”

Three other couples—Noyes’ sisters and their husbands and Mary and Stephen Leonard—joined the marriage that year, and the 10 signed an agreement saying, “all individual proprietorship either of persons or things is surrendered” and “John H. Noyes is the father and overseer whom the Holy Ghost has set over the family thus constituted.” John and Harriet Noyes moved into the Cragins’ home, while Noyes’ sisters welcomed the Leonards into their family home nearby. The other 25 members of the Society were kept in the dark about this new martial arrangement. In her research, Wayland-Smith found no evidence that John Humphrey Noyes had sex with his sisters.

Their complex marriage would not remain a secret for long. Noyes, who had taken to practicing faith healings (one that worked, and another that failed), confided in a new friend about his multiple relationships. During the fall of 1847, that pal betrayed him and took the news of Noyes’ extramarital affairs to the Vermont attorney. Noyes was arrested on charges of adultery in October but quickly released on bail. The Putney villagers’ outcry about the group’s amoral behavior caused them to flee to a Perfectionist’s farm on Oneida Creek in New York, part of the former Oneida Native American reservation, in early 1848.

This 1933 Community Plate ad describes the new “Lady Hamilton” pattern as “the essence of modern distinction, and the birthright of true aristocracy.” Click on the image to see it larger.

There, Noyes decided that, in order to abolish “egotism and exclusiveness,” the members of the group, now called the Community, whose ranks had swelled to 84, should live under one roof. Fortunately, the Community had attracted a large number of craftsmen like carpenters who helped construct a three-story dwelling called the Mansion House. Not satisfied to contain the kingdom of heaven to this little rural outpost, Noyes quickly set up branches in Brooklyn (1849-1855) as well as Wallingford, Connecticut (1851-1880). In Brooklyn, Noyes launched a weekly newspaper, “The Free Church Circular,” to promote his theology of Bible Communism.

“Most religions have a mystical branch that wants to dissolve the separate, individual selves into some larger whole called heaven, or the Over-Soul, if you want to use Ralph Waldo Emerson’s term,” Wayland-Smith explains. To create heaven on earth, Noyes expected his followers to dissolve into the greater whole through fully communal living. “John Humphrey Noyes’ communist philosophy goes back to the Bible. He quotes the Acts of the Apostles, which says on the day of the Pentecost, ‘all the believers were together and had everything in common. They sold property and possessions to give to anyone who had need.’ (Acts 2:44-45)”

The first tenet of Noyes’ Bible Communism was to let go of emotional attachment to other people, be they spouses or even children, in exchange for a communal spirit fed by God’s love. Married couples who joined the commune were told to give up their “marriage spirit” of sexual possessiveness and jealousy. Mothers and children or pairs of lovers who showed too much attachment or “sticky love” would be punished with periods of separation.

The Oneida Community children and their caretakers pose with a structure they called Rustic Summer House, circa 1870s. (From the Oneida Community Collection at Syracuse University Library in New York)

“Noyes was canny to see that if you just give up possessions, you’re not going to get rid of selfishness because selfishness attaches to people and families,” Wayland-Smith says. “If you don’t get rid of the kinds of attachments that you have to wives and children, you’re never going to reach the state of absolute equality among all the members of Christ’s body. That was the impetus for getting rid of what the Oneidans called ‘special attachments’ or ‘sticky love.’”

At Oneida, another building on the former farm was converted to the “Children’s House” where all the Community’s children, ages one and half to 12, would be raised by nurses and teachers. Noyes believed that favoring one’s own children over others, or “philoprogenitiveness,” was also a sin.

“The amount of self-restraint, self-chastisement, and suffering that the Community members had to go through to maintain complex marriage was extraordinary.”

“Around one and a half years of age, the children would go into the Children’s House,” and “They could see their mothers every day during formal meetings where they would have tea or play together. If there was a sense that the mother was too attached or the child was too attached, the Administrative Council would slap these separation periods on them, saying ‘You can’t see each other for two weeks until you can prove that you’re not overly attached to each other.’ When you read the mothers’ stories about being separated from their kids, it was so painful and horrifically hard. But the Oneidans’ idea was that if you show partiality to any one member, the whole commune falls apart. When my grandmother’s generation talked about the social side of the Community, they would say its attempt to engineer maternal affection or romantic attachment out of people was doomed from the start.”

Noyes didn’t see any conflict between scientific progress and his brand of Christianity: Like many Victorians, he was mystified and enchanted by electricity and magnetism. Noyes combined ideas from Franz Anton Mesmer’s theories of animal magnetism and Ralph Waldo Emerson’s concept of the Over-Soul, wherein everyone and everything is a connected part of God. He asserted that Christ’s love was an electric fluid that could be passed through words, both written and spoken, as well as through touch. But the ultimate way to charge up the Community’s “God battery” was through sex, and if the members had enough electric sex in the name of Jesus, they could achieve immortality on earth. And Noyes believed he could prove his utopia’s path to everlasting life through scientific study.

This photo from June 25, 1863, shows the newly completely Mansion House (right) next to the old (left). The expansion of the new Mansion House was completed by 1878. (Photo by O.A. Hollenbeck. From the Oneida Community Collection at Syracuse University Library in New York)

“In his writings, Noyes talks about Jesus being a battery, and that if you plug into him, he will charge you with this electric life which eventually that will lead to immortality and bring about the Resurrection,” Wayland-Smith says. “Noyes took all these religious ideas about the Resurrection and tried to come up with these empirical explanations for how scientifically they’ll happen. Today, it sounds strange. But at that time, science was the lingua franca that everybody was using to explain how the world worked. As Americans faced a shift from a religious view towards a scientific view of the world, Noyes was trying to marry the two.

“His ideas about electricity were very current,” she continues. “Franz Anton Mesmer, for example, theorized that you could heal sick people through these magnetic touches, which could reset your ‘magnetism.’ Floating around the medical literature of the day were theories about electric vital fluid becoming out of balance. John Humphrey Noyes took these ideas to a theological plane. When he was doing faith healing, he said when you are sick, it’s because your magnetism is blocked, and if you get the electricity flowing properly, then you will be healthy.

“Noyes also believed that the Resurrection, or the unification with the body of Christ, will happen when each individual body can get the electricity flowing so evenly that there won’t be any blockages in the system,” she says. “He saw magnetism was at work everywhere: It was at work when you touched people, and when you read words on a page, there was some sort of magnetic transfer that happened from the mind of the person who wrote them to the person who was then reading them. He believed some ways of communicating this universal fluid were more effective than others, like having sexual intercourse.”

This 1911 Oneida Community, Limited, ad from “Ladies Home Journal” shows a couple pondering silverware. It’s the first Oneida ad drawn by illustrator Coles Phillips. Click on the image to see it larger. (From the Walt Reed Illustration Archive at Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri)

As the Community’s children became teenagers, their untamed libidos threatened to destabilize the system of complex marriage, so Noyes came up with a workaround: Each boy coming of age, usually around 14, would be introduced to sex with a spiritually devout postmenopausal woman. Meanwhile, girls who’d gone through puberty—at that time, New York’s age of consent was 12—would lose their virginity to Noyes himself (who was already 37 when the Community settled in Oneida). While there are no records of brother-sister or child-parent partnering, the Oneidans accepted sexual relationships between uncles and nieces as well as first cousins.

“The word ‘interview’ was the Oneidans’ euphemism for a sexual rendezvous,” Wayland-Smith says. “It was mostly men who requested the interviews, but they would never ask a woman directly. A couple of older, respected women of the Community acted as go-betweens. A man would say, ‘I want to have an interview with so-and-so,’ and he would ask this go-between to speak to the woman. In theory, a woman could decline without being embarrassed. In practice, the group was small enough that there was definitely social pressure like, ‘It will be good for you to sleep with this person.’

“I’m absolutely certain that the Oneidans kept track of everything, when people were initiated into the sexual life of the Community,” she continues. “One point, they decided things were getting too murky, when people started going off and having sex by themselves without going through the go-between. They literally had a notebook where they would keep track of who requested an interview with whom and when the encounter happened. All those things got burned.”

The full Oneida Community, probably circa the late 1850s. (From the Oneida Community Collection at Syracuse University Library in New York)

Today, the practice of older adults having sex with newly pubescent teenagers and the Community’s casual attitude toward incest is upsetting, to say the least. But the Oneidans also pushed back against Victorian ideas about sex in ways that we’d consider positive, healthy, and almost feminist. After watching his wife, Harriet, suffer through four pregnancies that led to premature births and babies too weak to survive, Noyes conclude that sex shouldn’t be simply for the purpose of procreation. He promoted a new concept of “amative” or loving sex—as long it was the communal love of Christ and not the obsessive love of romance flowing through the lovers.

“At the end of her five-year period of back-to-back pregnancies, Harriet was just ragged emotionally and physically,” Wayland-Smith says. “Noyes thought enough is enough. This is brutal. If a woman can’t control her reproduction, she doesn’t have time for anything else. She doesn’t have time to develop herself as a spiritual or an intellectual person. It’s amazing that the Oneidans understood that and gave that freedom to the women.”

Noyes even came up with a physical means of preventing pregnancies. Buying into the prevailing Victorian pseudoscience of the day, which said a man who “spills his seed” (or masturbates) erodes his “natural vigor,” Noyes wrote an essay called “Male Continence” where he encouraged his male followers to resist ejaculating at all.

A group of “stirpicult” children ride a wagon in front of the Mansion House in the 1870s. (Courtesy of Picador)

“At the time, there were free-love communes where you were allowed to couple up indiscriminately, and those usually didn’t go so well,” Wayland-Smith says. “The amount of self-restraint, self-chastisement, and suffering that the Oneida Community members had to go through in order to maintain complex marriage was extraordinary. It was not by any means free. It was very challenging.”

“The word ‘interview’ was the Oneidans’ euphemism for a sexual rendezvous. It was mostly men who requested the interviews, but they would never ask a woman directly.”

In 1869, Noyes, inspired by theories of evolution by Charles Darwin and Francis Galton, instituted his own eugenics experiment he called “stirpiculture.” Unlike other eugenicists that followed, Noyes wasn’t interested in eliminating certain races (everyone in the Oneida Community was white), physical features, diseases, or deformity—Noyes wanted to breed his followers based on their moral natures, hoping the holiest among them would give birth to a race of immortals—which he called “stirpicults”—hastening Christ’s kingdom. (In the decade stirpiculture lasted, 10 of the 62 stirpicults born were fathered by Noyes himself, who was then between the ages of 58 and 68 years old.)

“Fifty-three women of child-bearing age signed a pledge, saying ‘We will, if necessary, become martyrs to science, and cheerfully renounce all desire to become mothers, if for any reason Mr. Noyes deem us unfit material for propagation,’” Wayland-Smith says. “In the end, the Community let couples come forward and fill out applications to have babies, which then went before a committee. It wasn’t as directed as one would think. When it got announced, there were 51 applications and 42 of them were accepted. We don’t have details about why those nine couples were rejected.”

An Oneidan woman named Anna Bolles sports the short hair, plain dress, and pantaloons that were standard in the Community. She’s using a mop-wringer invented by Community member John Leonard. (From the Oneida Community Collection at Syracuse University Library in New York)

Both vanity and accumulating material possessions were frowned on in Oneida. For practical reasons, the Oneidan women cut their hair short, forewent the corsets Victorian women generally wore, and sported pantaloons under their plain dresses.

“When you see pictures of the women, you see they hacked off their hair at ear’s length,” Wayland-Smith says. “It doesn’t look that attractive. But it was easy, and the Oneidans felt that they shouldn’t be focusing on the body and superficial appearances. Instead, they focused on becoming smarter and spiritually enlightened.”

While Noyes did not consider women to be on the same spiritual level as men, the Oneida labor practices also gave women a substantial amount of liberty—freedoms that the suffragists of the day wouldn’t dare suggest. Thanks to the Children’s House, women were released from the burdens of domestic work and child care, so they were allowed to perform the same hard physical labor as men. Men, meanwhile, were encouraged to do domestic tasks like laundry alongside the women. Women were even welcome to try “brain work” like writing or editing for “The Circular.”

A group of Oneidans—men, women, and children—prepare to work together to clear the lawn. (From the Oneida Community Collection at Syracuse University Library in New York)

“Oneidans never for a minute pretended that women were equal to men,” Wayland-Smith says. “Theologically, they had a pecking order. They would cite Paul and say that a man’s natural place is ahead of the woman. But on the ground, practically, women could do anything that men could do. They thought it was absurd that Victorian women wore long skirts and corsets and had this big pile of hair that prevented them from moving or being physical, which the Community believed contributed to the poor health of traditional housewives. The women of Oneida engaged in the same physical activities as men, and the Community thought that was healthy. Women played sports. They went out and chopped down trees; they cleared swamps.

“Noyes took all these religious ideas about the Resurrection and tried to come up with these empirical explanations for how scientifically they’ll happen.”

“Oneida broke down the popular idea that there was a domestic sphere where women excelled and a public sphere where men excelled,” she continues. “The workload occasionally fell into stereotypical divisions. Most of the people who worked in the Children’s House were women, although there were some men taking care of the kids, too. But the men had to do laundry side by side with the women, and the women could work in the trap shop if they wanted. A lot of women were bookkeepers for the Community businesses. One woman wanted to be a dentist and so she took lessons from the Community dentist and became a dental assistant. Within reason, Oneida offered a wide variety of choice in one’s occupations.”

Just as he didn’t see the contradictions between science and faith, Noyes saw no conflict between his ideas of communal labor and equal reward with selling products on the capitalistic free market. Initially, Noyes and company tried their hand running an orchard, growing fruits in Oneida Creek’s verdant valley. But the harsh winters made it difficult for the commune to turn a profit. Fortunately, Seymour Newhouse, a master animal trap craftsman, was among Oneida’s ranks. Other Oneidan men were expert machinists who figured out how to build factories that would produce high-quality traps. The Community followed the success of its trap-manufacturing business by opening a factory that produced twisted silk thread for sewing machines. While the women of Oneida eschewed vanity, the Community benefited from Victorian women’s obsession with the latest trends—the traps provided them with the most chic furs while Oneida’s threads were always offered in the season’s hottest colors.

A 1911 Oneida Community, Limited, ad boosts the reliability of its “Victor Traps.”

In the beginning, the Community’s hybrid of communism and capitalism and the work-life balance it offered the Oneidans was downright, well, utopian. “At first, they had these very sane work hours, four to six hours a day, and their duties were always shifting,” Wayland-Smith says. “If you got tired of working in the trap factory, you could work someplace else. It was always balanced between domestic and trade labor.”

During the day after his or her work shifts, an Oneidan would be free to study the Bible, read literature, learn another language, practice a musical instrument, play sports, or take a walk in the woods. After dinner, the Community had its nightly meeting, often followed by a concert, dance, reading, or performance of some sort.

“The Oneidans were avid music fans, and they all played instruments,” Wayland-Smith says. “The Community had dances and nightly concerts. They had a 4,000-book library and were constantly ordering new books. Every night, they would pick a novel to read aloud, and anybody who wanted could come and listen. It was a very literate culture. They were avid for education. They educated the children in their own schools, but they also had adult classes in subjects like Greek, physics, and chemistry. Anything that a Community member could teach would be offered as a class.”

Fruit labels from the original Oneida Community. (From the Oneida Community Mansion House Facebook page)

As dreamy as this all sounds, Oneidans had to subject themselves to intense scrutiny called “Mutual Criticism” at their nightly meetings where other members gave them feedback on everything from the way they walked to whether they were engaged in sticky love. The Oneidans were also not allowed to accumulate any personal possessions other than basic furniture and clothing. Only a small fad for pocket watches among young men, late in the Community’s 32-year life, violated this ethical code.

“Oneidans didn’t have jewelry and wore the standard, simple clothing of the Community,” Wayland-Smith says. “They never handled money. To me, some of the most fascinating things to research were what happened when the Community dissolved and people handled money for the first time. Some had grown having never even seen it. John Humphrey Noyes’ son Pierrepont was a boy when the Community broke up. He wrote that it seemed strange to him that you would have possession of something like a snow sled and it wouldn’t be shared with a larger group.”

When the Community numbered 200 in 1851, the members built an extension to the Mansion House. By 1860, the Oneidans’ ranks had reached 250, and they elected to build a “New House” on the property that was twice the size of the old Mansion House, which officially opened for use on February 20, 1862. The New House was designed in an Italianate-villa country-home style to convey middle-class respectability and Christian civility to the outside world that often mocked the Oneidans for their myriad departures from convention. The Community members with green thumbs even cultivated a bourgeois-style manicured lawn, which allowed Oneidans to compete in croquet tournaments.

Members of the Oneida Community took to the middle-class hobby of croquet, circa 1865-1870. (From the Oneida Community Collection at Syracuse University Library in New York)

As it turns out, Oneida’s idealistic work conditions could only put out so much product. Eventually, in order to maintain their leisurely lifestyles and competitive edge in the market, Oneidans had to do the very thing they abhorred: Hire wage labor to work at their factories. The so-called “hirelings” sometimes put in 12-hour workdays, while the Oneidans still only worked around four. The thread factory employed girls, ages 10 to 16, because their small fingers were best suited to handling the thin strands of silk.

“As their products took off, the Oneidans realized that they couldn’t compete unless they started playing by capitalist rules, which meant hiring wage labor.” Wayland-Smith says. “For about 15 years before they broke up, they were employing wage labor, which they had adamantly said was against communism and against God’s plan for earthly paradise. So they had to live that contradiction.

“While Oneidans believed that all labor was noble, when push came to shove, if they could get somebody else to do the laundry, they were going to do it,” she continues. “Anthony Wonderley, who is the curator of the Oneida Mansion House Museum, has a book coming out in the fall about the work habits of the Community. He says that once it went over to wage labor and the Community members were no longer working as much, there was a depression and decline in the communal feeling that kept the Community together—this energizing ethic of laboring all together, men beside women, children beside adults. Once they left that to the laborers and retreated to their domesticity, they felt a sense of loss.”

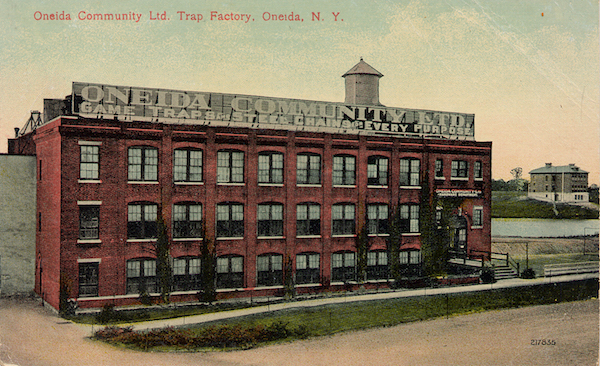

A 1905 postcard shows the Oneida Community, Limited, trap factory. (Via Trapper & Predator Caller)

Always looking for ways to stay afloat, the Oneida Community was open to try any sort of enterprise it could muster, including a failed attempt at making and selling chain link. In 1877, Wayland-Smith’s great-great-grandfather, Charles Cragin, who was living at the Community’s colony in Wallingford, Connecticut, was struck with a new inspiration.

“There was a silverware factory right on the Quinnipiac River downstream from the Oneida Community’s branch homestead,” Wayland-Smith says. “And one day, my great-great-grandfather was sitting on the banks of the river and watching the factory downstream churn out its silver with the river power. He thought, ‘We are right here on the river, so we could do that, too.’ So they built a factory and the machines needed to punch out the spoons. In the beginning, they were just making tin spoons, down-market stuff, and it expanded from there.”

Around that time, fissures were starting to spread within the Oneida Community. The aging Noyes was going deaf and couldn’t speak at meetings. Some of the sons of the original members had gone off to college and returned with a good deal of skepticism about the Community’s religious beliefs. Other members started to petition Noyes to replace his theocratic communism with democratic rule, which would embrace the individualism and competition that fed the capitalistic world outside.

John Humphrey Noyes, pictured in the 1870s, became deaf as he aged. (Courtesy of Picador)

“First of all, and most importantly, John Humphrey Noyes’ decline drove the Community to its end,” Wayland-Smith says. “He was the Community’s charismatic center and held it together at some level. Elderly and deaf, he was obviously no longer the leader or the sexual magnet he once had been.

“Then in the 1860s, the Community sent 10 or 12 of their young men to Yale to get degrees in engineering, medicine, and mathematics,” she continues. “That experience in the outside world and with the larger currents of positivism and science changed how they felt about John Humphrey Noyes’ religious dispensation. They began to doubt that he was really the prophet he said he was.”

Outside the Community, a renewed Christian crusade was boiling up against anything that broke with the norms of traditional marriage—from pornography and contraception to unorthodox relationships. The Comstock Law, passed by Congress in 1873, forbade mailing or selling any material considered “obscene.” In 1878, the Supreme Court ruled to ban polygamy in Utah Territory, where the Mormons had settled. Inspired by the ruling, John Mears, a Presbyterian minister at Hamilton College, wrote an editorial for “The New York Times” on April 10, 1879, skewering lawmakers for ruling against polygamy but not doing anything to stop the “systemic concubinage” at Oneida Community. In June, the “Syracuse Standard” reported that the Central New York authorities were preparing to have John Humphrey Noyes arrested, so under the cover of night, Noyes fled to Canada.

Members of the Wallingford, Connecticut, branch of the Oneida Community pose outside of their home in 1876. (From the Oneida Community Collection at Syracuse University Library in New York)

“When the Supreme Court decided to outlaw polygamy in the Utah Territory, that was the death knell for non-monogamy,” Wayland-Smith says. “Up until that point, it had been up in the air whether polygamy would be tolerated in the United States, and obviously, complex marriage was a version of that. The country was taking a conservative turn. When John Humphrey Noyes became alarmed and escaped to Canada, that was the beginning of the end because he was no longer at Oneida to direct things.”

“While Oneidans believed that all labor was noble, when push came to shove, if they could get somebody else to do the laundry, they were going to do it.”

With the end of the Community on the horizon, the future didn’t bode well for the women, who often had children with multiple partners (who often had children with multiple women themselves). In the outside world, the single Oneidan women and their children would suffer, labeled as “adulteresses” and “bastards.”

The upstarts within the Community wanted to open up complex marriage so that they could have sex without the approval of a go-between, but Noyes and his loyal followers objected, insisting this approach eroded the holy purpose of Oneida communal love-making. In August, Noyes sent notice from Niagara Falls, Canada, calling for a vote to end complex marriage, in order to protect the women and children. He advocated for celibacy before monogamous marriages, which would have to be approved by the Administrative Council.

The Community voted overwhelming in favor of Noyes’ proposal, which set the end of complex marriage for 10 p.m. August 28, 1879. Many Oneidans spent that day in the arms of their favorite lovers. A niece of Noyes’ named Tirzah Miller had one last final promiscuous hurrah, having sex with three different men before 10. “Tirzah Miller had problems getting too attached to people, but she also enjoyed the polyamory, as she was a very libidinous woman,” Wayland-Smith says. “The Oneidans called her a ‘social magnet’ because she liked having sex with lots of different partners, and it worked for her.”

John Humphrey Noyes’ niece Tirzah Miller, known as a “social magnet,” gave birth to two “stirpicults” by two different fathers. (Courtesy of Picador)

In the weeks after complex marriage ended—to John Humphrey Noyes’ disappointment—the younger members of the Community ignored his pleas for celibacy and rushed into traditional marriages. Finally, in August 1880, it was resolved that the Oneida Community should break up and restructure its businesses as a joint-stock company, Oneida Community, Limited. The shares were divided based on who initially invested the most money into the Community, as well as how much labor the individual put into it. Despite the mad scramble for men and women to pair off and form traditional nuclear families, some women and children were inevitably left behind. While a few women were fortunate enough to marry partners with substantial amounts of Oneida shares, a handful remained single mothers and struggled to survive.

“The leaders did the best they could to match people up,” Wayland-Smith says. “But yes, there were some women who didn’t get husbands and ended up quasi-destitute. Not a lot of women, but a few. Harriet Worden had three different kids by three different fathers, and she didn’t get married at the end. But one of her sons was Pierrepont Noyes, who would come back and rebuild Oneida into a silver company. He quite openly said in his autobiography that because he was a bastard, he knew he would have to work twice as hard to make it in the world. He was determined to redeem himself and his family, which he did.”

In the beginning, Oneida Community, Limited, floundered, too. After the elder Noyes passed away in 1886, the older former Community member were still running Oneida’s multiple enterprises—thread, animals traps, canned produce, and flatware. These devoted Oneidans still looked to Noyes for spiritual and business guidance through séances, which were hugely popular at the time. When Pierrepont, one of Noyes’ stirpicult children born during the Oneida eugenics experiment, overtook the company in 1895, he wasn’t having any of the Spiritualist nonsense. Thinking like a businessman, Pierrepont Noyes evaluated the economic prospects of each product and, by 1900, determined Oneida should drop the thread-making and canning businesses. Trap-making would be slowly phased out and discontinued in 1925. Pierrepont invited several of his stirpicult contemporaries to return and take leadership positions at the company.

In this Oneida Community, Limited, advertising poster, the character “Johnny Sneak’em” asserts, “The Victor trap alone stands between me and starvation.” Click on the image to see it larger.

“When his group gained the majority vote on the board of directors, nothing was making a profit,” Wayland Smith says. “Pierrepont decided everything except the silverware was not a winning ticket. The thread didn’t turn much of a profit even in the best of times because buying the raw silk was so expensive. The fruit canning couldn’t compete with national companies. I think he saw where traps were going in terms of the future of animal rights. He decided to put all of Oneida’s eggs in the silverware basket, and it was a gamble that ended up paying off.”

At the time, a couple of prominent companies were dominating the sterling-silver market. But the next tier of flatware, known as triple-plate silver or silverplate had potential. At the time, triple-plate came in early Victorian patterns that were considered old-fashioned and fussy. Because it wasn’t so much cheaper than sterling, middle-class families scrimping and saving for silverware would simply hold out until they could afford a sterling set. Pierrepont Noyes and OCL stepped into the void in the silverplate market, offering a brand called “Community Plate” in fresh, “modern” patterns to young middle-class couples who wanted nice cutlery that was a bit more affordable.

A Community Plate ad—introducing a utensil “for the service of pies, pastries, and fish” in the “Grosvenor” pattern—places the silverware on an intricate lace background. (Via Nancy Eleanor Gluck’s Silver Threads blog)

“Pierrepont Noyes saw a market for people who were caught in between what one jewelry store owner called ‘the hired girl’s silverware,’ which was the down-market silverware, and the high-end sterling,” Wayland-Smith says. “Oneida cornered that market by making the triple-plate product even better, so that the metal didn’t wear through as quickly as the competing brand. They also made it more attractive by issuing it in hip new patterns that style-conscious people would want to buy.”

As Oneida Community, Limited, presented its silverplate flatware as the epitome of urban elegance and taste, the stirpicult generation and their children—150 people total—returned to the Mansion House, where they lived in semi-private apartments within the house until their nuclear family units got too big for them. Then, the individual families would build houses nearby, creating a village they called Kenwood. Single stirpicults often ended up marrying other Oneida descendants.

Adopting a more heteronormative lifestyle than their ancestors, the men took management jobs at Oneida, which they ran like a boys’ club, and women reigned in the domestic realm. In that way, the company did its best to combat the Oneida Community’s reputation for letting masculine, oversexed women run amok in the mid-1800s. In the spirit of “The Circular,” the family published a newsletter called “The Quadrangle.” “They were not particularly religious, but they had a fierce allegiance to their family and to the company,” Wayland-Smith says. “That took the place of religion.”

When Pierrepont visited the home of one of his factory workers in 1895 and saw the deplorable conditions he lived in, he resolved to lessen the poverty and suffering of Oneida’s laborers. His decision was canny, as the socialist labor movement was just gearing up for battle with the greedy titans of industry who had run roughshod over their factory workers with low pay, long hours, and abhorrent working conditions. Pierrepont began to pay OCL’s factory workers above-average salaries and developed a system of profit-sharing to inspire efficient work. The company also offered its employees cheap land and loans to erect homes, creating a village near Oneida called Sherrill. OCL then built a school, a shopping district, a community center, and sports fields in Sherrill, which provided athletic activities, movies, and lectures to keep workers from leaning on drinking for entertainment. As more and more companies responded to the growing threat of a labor uprising, none of these innovations meant to keep workers happy were particularly unusual for the early 20th century.

Oneida Limited introduced its “Coronation” silverplate pattern in 1936 to honor the crowning of Edward VIII as King of England. The pattern, seen here with a “Community” mark, remained popular even after Edward abdicated his throne.

What was striking was the company’s policy of having management take the brunt of financial hits. Instead of laying workers off in hard times, managers would take deep cuts to their salaries. Giving the philosophies of his father a secular bent, Pierrepont encouraged all his cousins at Kenwood to embrace a modest lifestyle and reject the greed and extravagance of the American moneyed class. Unlike his father, though, Pierrepont didn’t see the working class as equals with the white-collar employees. Instead, he believed the privileged should learn to behave in a way that showed compassion for the have-nots. As result, a labor organizer who visited Oneida in 1915 was befuddled to find the workers weren’t interested in forming a union.

“Americans couldn’t accept that the new model for the economy was going down this path towards ‘selfishness.’ That is one of the reasons why John Humphrey Noyes, who otherwise had some very strange ideas, attracted followers.”

“In the 1910s and ’20s, the rise of the Socialist Party created a looming sense that a confrontation coming between workers and capital was coming,” Wayland-Smith says. “Modifying the socialist values of John Humphrey Noyes, Pierrepont Noyes asserted that the relationship didn’t have to be antagonistic and adapted his father’s ideas about a spiritual brotherhood among all men. Pierrepont felt that there were people who were meant to be management and people who were meant to be workers, so his father’s idea of absolute equality didn’t really work for him.

“Pierrepont’s concept was a very paternalistic philosophy,” she continues. “What separates it from the trickle-down and other new mutations of paternalism is that when the company was in trouble financially, the hits happened across the board. In fact, the managers would take 20 to 30 percent pay cuts rather than fire their workers because they knew they were materially comfortable enough that they could take that hit. The social justice depended on the noblesse of the management class. But Oneida’s workers never formed a union because they trusted the management to treat them correctly.

“At Kenwood, the Oneida family very much wanted to maintain a facade of bourgeois respectability,” she says. “But as management, they completely eschewed material accumulation. That ideal from the utopia stayed with them. For instance, I never inherited any silverware; the family themselves didn’t use their silverware.”

A 1920s Community Plate ad played on middle-class housewives’ fears that they would be shamed by setting out or serving with the wrong utensils. Click on the image to see it larger.

That said, as much as the Oneidan descendants had a personal distaste for accumulating material status symbols, the company was happy to exploit the hopes and fears of social climbers to make a profit. In 1904, Pierrepont Noyes hired fellow stirpicult Burton “Doc” Dunn as the company’s advertising director. Dunn came up with the brilliant idea running full-page ads featuring photographs of Oneida flatware pieces against the finest lace he could find. Dunn spared no expense purchasing lace from museums, art galleries, and antiques shops. The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City lent him priceless lace to match his silverplate patterns. When he couldn’t find the ideal lace pattern, he commissioned it. The type of laces pictured in the ads communicated specific messages to women and suggested what Wayland-Smith calls an “aura of genteel Old World elegance longed for by every middle class housewife.”

“Most religions have a mystical branch that wants to dissolve the separate, individual selves into some larger whole called heaven.”

“In its heyday, the company made its fortune on convincing these middle-class housewives that you had to have a fork for every course and special utensils like grapefruit spoons,” Wayland-Smith says. “They kept multiplying the number of proper utensils you had to have in order to set a proper bourgeois meal. If you read some of the ads from the 1920s, they would spell out these fears about keeping up with the Joneses, like ‘It just isn’t done in polite society anymore to use the same fork for the salad and the main course.’ But of course, the family themselves didn’t buy into any of that. They were so tuned in to the nuances of class and its material markers and yet were completely uninterested in those markers themselves.”

Dunn had another stroke of genius when he hired society illustrator Coles Phillips in 1911 to depict happy couples and convince men that they were involved in cutlery decisions, too. In the wake of that successful campaign, Phillips created a series of Oneida ads focusing on elegant young women. While they looked like liberated flappers with their bobbed hairdos and modern clothes, Phillips’ “pretty girls” pined for traditional marriage and moneyed respectability. In several of his ads, the woman looks tenderly into an open chest of shining Community Plate. The viewer, however, can’t see the contents of the chest, only the sweet expression of the young woman admiring at it. “It looks a lot like she’s opening the Ark of the Covenant,” Wayland Smith says. “And I don’t think that was coincidental.”

This 1920s Coles Phillips ad for Community Plate doesn’t even show the silverware—just the woman’s reaction to it.

While most of the Oneida descendants at Kenwood in the 1920s wanted to keep the Community’s sexual explorations hush-hush, two of the family’s black sheep, George Wallingford Noyes and Hilda Herrick Noyes became fascinated with exhuming those secrets. Hilda, in particular, wanted to prove that the stirpiculture experiment was in-line with the current scientific eugenics movement, which was tricky because the Oneidans had focused on morality and not measurable genetic traits.

“The Oneida descendants were so tuned in to the nuances of class and its material markers and yet were completely uninterested in those markers themselves.”

“Hilda and George put together a study to prove the stirpicults were heartier and more intelligent for a conference on eugenics held at the Natural History Museum in New York in 1921,” Wayland-Smith says. “A cousin of mine found index cards in his attic with Hilda’s documentation of the stirpicults. She kept careful notes of their health and statistics, which she later gathered in a notebook, but these are her original cards, we believe. For the conference, Hilda and George wrote articles and delivered speeches, but they were not well-received, precisely because the stirpicults were conceived outside of wedlock.”

Meanwhile, the company sought out celebrity endorsements for Community Plate, making a big deal of the fact that Princess Margrethe of Denmark received a gift of Oneida silverware when she married Prince René de Bourbon in 1921. A 1926 ad read, “When a Princess Weds,” she is gifted with a “magnificent cabinet” of Community Silver. To celebrate Edward VIII’s crowning as King of England in 1936, the company issued a pattern called “Coronation,” which was popular with American housewives dreaming of aristocratic luxury despite the fact Edward abdicated his throne. “Deauville,” “Noblesse,” “Duchess,” “Countess,” “Royal Rose,” and “Lady Hamilton” were all patterns based on the same regal aspirations. In 1929, Oneida acquired its competitor, Wm. A Rogers, and its “1881 Rogers” mark, as well as its beloved patterns.

Oneida’s “Nobility Plate” silverplate line made its aspirations of royalty explicit. This group of serving pieces—sugar spoon, pierced tablespoon, regular table spoon, cold-meat fork, and tomato server—is in the “Royal Rose” pattern, which was introduced in 1939.

When the United States entered World War II in 1942, the government conscripted the company, now called Oneida Limited, to manufacture wartime necessities like parachute hardware, surgical instruments, bayonets, M74 bomb casings, engine bearings, and Curtiss propellers for Helldiver bomber plans. Worried about Community Plate losing awareness among American consumers, Oneida enlisted the help of Jean Wade Rindlaub of the BBDO advertising firm, one of the first ad women on Madison Avenue. “Rindlaub thought of a way to keep silver in the minds of buyers even though they couldn’t go to the jewelers and buy it like they had before,” Wayland-Smith says.

“It looks like she’s opening the Ark of the Covenant. And I don’t think that was coincidental.”

Rindlaub intuited that, amid the confusion of the war, many American women longed to have their sweethearts return so they could make a home together. Employing illustrations by Jon Whitcomb, she created ads depicting women embracing their uniformed lovers called “Back Home for Keeps.” Oneida silverplate, naturally, would be a part of this dreamy domestic post-war scenario. The ad struck such a nerve, American women and homesick soldiers sent hundreds of thousands of requests for prints, making “Back Home for Keeps” a popular pin-up poster that offered hope for men and women alike. Once the war ended and Oneida Limited was able to resume production of Community Plate, Rindlaub and Whitcomb seamlessly transitioned their wartime ad campaign into a peacetime scene of domestic bliss titled “This Is for Keeps.”

“Rindlaub is believed to be the person who came up with the concept of focus groups,” Wayland-Smith says. “She gathered all the women who worked as secretaries at BBDO and divided them into ‘matrons,’ who were older and had children, and younger women. She asked them about their hopes and dreams. She found that most of them didn’t care about their careers, they wanted to get married and have children.”

During the war, ad woman Jean Rindlaud kept Oneida silverplate at the top of people’s minds with her “Back Home for Keeps” campaign, illustrated by Jon Whitcomb. After the war, the slogan was altered to “This Is for Keeps.” Click on image to see the ads larger. (Courtesy of Picador)

In spite of the growing Red Scare about the spread of Soviet-style Communism, Wayland-Smith says she doesn’t think Oneida Limited felt any need to hide its Christian socialist roots. After doing her research, she believes the burning of George Wallingford Noyes’ archives in 1947 had more to do with postwar America’s renewed obsession with traditional family values and Oneida’s desire to hide its “wild, mannish” women of yore.

“The Lavender Scare, which came out of the Red Scare, was a fear of homosexual activity as well as anything that deviated from the heteronormative nuclear family standard, anything that could be considered sexual impropriety,” she says. “At the time, there was a paranoia about ‘oversexed women’ like Soviet spies who could seduce secrets out of men.”

So in its extravagant 1948 centennial celebration, the company trumpeted its legacy built on “principles of sharing and equality” and John Humphrey Noyes’ Bible-based combination of communism and capitalism, explained in a modified history of the Oneida Community written by Walter Edmonds, The First Hundred Years, 1848-1948; Oneida Community.

The “South Seas” Community Plate pattern embraced the 1950s tiki trend.

“The 100th anniversary celebration happened at the height of Oneida’s powers,” Wayland-Smith says. “In my research, we found a recording of the speeches given at the event. The management talked about Oneida’s special community. They were clearly conscious of the company’s legacy as a ‘city upon a hill’ with its improved worker-manager relationships and ideas about how you distribute wealth. But it was paternalistic capitalism and, they asserted, definitely not modern-day Communism. Oneida Limited promoted material equality—but only to a point.”

Shortly thereafter, Oneida’s executives realized the company was losing out to cheaper and easier-to-maintain stainless-steel flatware. Concerned the move would—ahem—tarnish its reputation, Oneida’s leaders reluctantly voted to manufacture stainless-steel cutlery. “When Oneida Limited started making stainless steel, many of the higher-ups saw it as the decline of the company, but Oneida took the time to make it beautiful,” Wayland-Smith says. “To its credit, Oneida was always quick to adapt to trends. Instead of digging in their heels and saying, “No, we only make sterling silver or silverplate,’ the company leaders decided Oneida should make stainless-steel flatware in better patterns than had been done before. Oneida became one of the top sellers of stainless-steel flatware, even though the executives initially disdained it.”

Wayland-Smith says her great-grandfather and grandfather had both been treasurers at Oneida Limited, and her father was expected to follow in their footsteps. But he defected and became a political science professor at a small college in western Pennsylvania. Despite her family’s “insider-outsider” status, in the 1970s and ’80s, Wayland-Smith often stayed at the Mansion House in Oneida, New York, during summers and Christmas break.

This 1981 Oneida Limited ad shows a kitten who’s been served milk in a porringer with a “Fantasy”-pattern spoon.

“The Mansion House was still subsidized by Oneida Limited, which spent a huge sum every year just to keep the thing running,” she explains. “At that point, it was like a retirement home. When they were young adults and had children, the descendant families had moved out of the Mansion House into homes surrounding it. When those people got older and became widowed, they moved back into apartments in the Mansion House. When I was a kid, my grandmother, my aunt, a series of great-aunts and uncles, and a lot of cousins lived there; they were all 60-plus years of age. It was a senior scene.

“They still had a quasi-communal lifestyle,” she continues. “Oneida still maintained a full kitchen staff and dining hall, as a lot of the apartments in the Mansion House didn’t have kitchens. People came downstairs to eat three meals a day the communal dining room. The house was also the heart of the village, and other villagers came in and out freely. The doors were never locked, so you could wander from apartment to apartment. The family had a very attenuated sense of personal privacy among themselves, which, I think, was holdover from the Community days.”

“What separates Oneida Limited’s philosophy from the trickle-down and other mutations of paternalism is that when the company was in trouble financially, the managers would take 20 to 30 percent pay cuts rather than fire workers.”

However, the Oneida Community descendants’ reign over Oneida Limited was coming to an end. Pierrepont’s son, P.T. Noyes, retired as president of the company in 1981, and from that point on, the head of Oneida would always be an “outsider,” although the family maintained seats on the board of directors. After the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, American Airlines removed metal cutlery from its planes, ending its relationship with Oneida.

The descendants on the board held fast to Pierrepont’s principles and refused to close American plants in favor of cheap labor overseas in early 2000s. Thanks to that, as well as some ill-thought-out acquisitions, the company filed for bankruptcy in 2006, which is when it gave up all pretense of equality. To please creditors, Oneida Limited jettisoned its laborers pensions and retiree health benefits, while executives kept their $300,000 retirement packages. The still-existing brand was then acquired by an outside company, and sold again in 2011, when it was merged with glassware maker Anchor Hocking.

“Oneida Limited never had a union, and as the family members started to drop out of the company, it became much more conventional in terms of worker-management splits,” Wayland-Smith says. “When it finally went bankrupt in 2006, the workers had no one to defend them, and they lost their pensions and, in some cases, their health care. It’s a lesson for why, whatever their lofty ideals are, you can never trust that a company’s management is going to be benevolent. It makes an excellent case for forming unions.”

(To learn more about the history of Oneida, pick up Ellen Wayland-Smith’s book “Oneida: From Free Love Utopia to the Well-Set Table,” published by Picador, and also visit the Oneida Community Mansion House. Learn more about American silverplate in general at Nancy Eleanor Gluck’s Silver Threads blog. If you buy something through a link in this article, Collectors Weekly may get a share of the sale. Learn more.)

Saving Vermont History, One Silver Spoon At a Time

Saving Vermont History, One Silver Spoon At a Time

Goat Rituals and Tree-Trunk Gravestones: The Peculiar History of Life Insurance

Goat Rituals and Tree-Trunk Gravestones: The Peculiar History of Life Insurance Saving Vermont History, One Silver Spoon At a Time

Saving Vermont History, One Silver Spoon At a Time Slut-Shaming, Eugenics, and Donald Duck: The Scandalous History of Sex-Ed Movies

Slut-Shaming, Eugenics, and Donald Duck: The Scandalous History of Sex-Ed Movies Sterling Silver FlatwareWhen it comes to antique sterling silver flatware, age is not everything. F…

Sterling Silver FlatwareWhen it comes to antique sterling silver flatware, age is not everything. F… Oneida SilverOneida Limited was not formed until 1880, but the roots of the company date…

Oneida SilverOneida Limited was not formed until 1880, but the roots of the company date… Silverplate FlatwareSilverplate flatware has been a popular, and less costly, alternative to st…

Silverplate FlatwareSilverplate flatware has been a popular, and less costly, alternative to st… Stainless Steel FlatwareAs early as 1821, scientists in Europe were experimenting with various iron…

Stainless Steel FlatwareAs early as 1821, scientists in Europe were experimenting with various iron… Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Great article! Just one note–Quakers were not “new” during the Great Awakening. They had been around since 1650 or so.

[Thanks for the comment. The text is corrected now.—Eds.]

Very thorough article here. But, by the same token as above, the Baptists and Methodist were not new sects either. Their numbers were burgeoning during the mid-nineteenth century but were started in the 17th and 18th century.

Upstate New York was known as the Burned-over District due to the many religious sects that were born in this region. The largest and most successful is the Mormon Church where its holy book, The Golden Plates” was found buried in a small hill outside the town of Palmyra, NY. Known as Hill Cumorah, the site hosts an annual Mormon pageant celebrating the birth of the LDS Church. Other religious sects tracing their start to Western NY are the Seventh Day Adventists and the Jehovah’s Witnesses.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Burned-over_district

Good article. One correction: It is not the Book of Revelations, but instead the Book of Revelation – no “s” Thanks.

I’d love to achieve immortality through sex – or die trying!

I taught at Colgate in the 1960s….and was intrigued about Oneida….it was a rebellious time in America including birth control, open marriage and sensitivity groups. Oneida was ahead of its time.

I visited and researched Oneida as a successful commune experience including Skinner’s based Twin Oaks in Virginia. I learned much from the article.

Thank you

What a different time in America now!

Great article on the history of Oneida Community. They were a fascinating utopia. As I am sure you research revealed, Oneida manufactured tons of different silverplate including many many lines that were sold by other companies. Nobility Plate was one of those lines. Nobility Plate was manufactured exclusively and under contract by Empire Crafts Corporation which was subsidiary of the C. H. Stuart & Co of upstate Newark, New York. Nobility was NOT a line of Oneida but a line of Empire Crafts. Empire Crafts sold Nobility Plate through at at-home direct sales network. Royal Rose and all 8 of their patterns were named by Empire Crafts and NOT by Oneida. The patterns were designed and patented by Oneida designers but that was the end of the connection. I am a member of the Neewark-Arcadia Historical Society in Newark and have been researching Nobility Plate and Empire Crafts Corp for some 20 years. You may be interested in checking out my website which details the history of Nobility Plate and Empire Crafts (nobilitysilver.com). Thanks

It is a fascinating article however this stated quote below is misleading to me, if not a tad uninformed where the author is quoted,

“The company made its fortune on convincing middle-class housewives that you had to have a fork for every course and special utensils like grapefruit spoons.”

Well, they were not wrong after-all nor were they the first to make such etiquette facts known, it was simply good business sense. What sophisticated person now or then would eat a multi-course meal with the same utensil? One has to just consider Victorian polite Society place settings, they took the proper form by taking various utensils to the extreme.

I have been trying to find out if Oneida’s Patrick Henry pattern was made of 18/10 stainless steel or a lower quality. Can anyone answer that question or at least where to research it?

Wow that was a wild ride! “ His ideas about electricity were very current,” 💀

Very well researched and written. What an interesting story! One thing, though: the title is a bit misleading by calling them Christians. By definition, a Christian is one who follows Christianity, and Christianity as a whole has never excepted polyamory. Saying their Christians because they read the Bible but don’t follow Christianity is like someone calling themselves a vegetarian because they read a book about vegetarianism but still eat meat.

I think it is also important to consider how religious cults may seem like utopias to those who are participating in it; however, utopia means no place in Greek. With the vast information about enduring present day cults (Latter Day Saints, Fundamentalists, Jehovah Witnesses, etc) and the cult-like behavior seen here with Noyes as a “charismatic leader”, I think the title is misleading. There are several well-known cults out there that made “goods” in their communes with the “service of others” in mind only to make money for their leaders.

I found a spoon marked Tudor Plated Oneida Community. It has a small floral design. It also is marked with USN above the design. Design reminds me of 1920s or 30s. I was wondering if this flatware was WWII or before. Sorry I did not include picture. tech illiterate.