A.C. Dwyer, an avid coin collector, talked with us recently about the history of U.S. $20 double eagle gold coins, especially those struck during the California Gold Rush. Dwyer discusses the types of double eagles that were minted, the most interesting and rarest varieties, and why he’s so enthralled with coins that have been found at shipwreck sites. Dwyer can be contacted via his website, acdwyer.com.

The double eagle is really a result of the California Gold Rush. Prior to the California Gold Rush, the biggest gold discoveries were relatively small strikes in Georgia and North Carolina. That led to new U.S. Mints in Dahlonega and Charlotte, and they struck smaller denomination gold. But in California, the amount of gold being found was so spectacular that in the beginning, people didn’t even believe it.

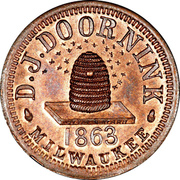

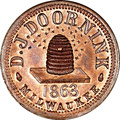

The San Francisco Mint struck two types of double eagles in 1866. The mintage of coins without an In God We Trust motto (above) was 120,000. The mintage of 1866 motto coins was 842,250.

When gold was first discovered in California, there wasn’t this immediate stampede that everybody thinks of. Instead there was a lot of skepticism, and the newspapers of the day were basically bashing the reports of the gold. It wasn’t until President Polk gave his last State of the Union speech in December of 1848 that he confirmed that the extraordinary stories of gold in California were true. And that’s what really kicked off the exodus to California.

Shortly after California became a state in 1849, there was a clamor for a mint in San Francisco. Until it opened in 1854, all the gold from the California Gold Rush—the vast majority of it, anyway—went by side-wheel steamer down to Central America, where it would travel overland through Panama or Nicaragua to the Gulf before being shipped to the mint in Philadelphia. Some of it would even go all the way around the horn of South America and back up the other side. But with a mint in San Francisco, they didn’t have to ship the gold anywhere.

You have to understand that the United States became a very wealthy country almost overnight. At the time of the California Gold Rush, the majority of coins that were in circulation were probably foreign coins that were legal tender alongside our own coins. Like the Mexican reale. Probably the most popular silver coin was the Mexican pillar dollar. Thanks to the Gold Rush, by 1857 we did away with all that foreign coinage—it was no longer legal tender here.

You have to understand that the United States became a very wealthy country almost overnight.

If you were going to be paying other countries in gold, you needed an efficient means of accomplishing this. At the time, the $10 eagle was our largest coin, so the double eagle made it much easier to do these large transactions. As a result, the double eagle probably didn’t circulate much, especially on the east coast since it was just going from bank to bank, or from U.S. to Europe to pay debts.

In fact, a lot of the gold eagles being collected today, especially a lot of the uncirculated coins, have come from Europe. They were repatriated as they became popular over here. Collectors would go over there and find them in foreign banks and ship them back. One of the coins I have in my collection has what’s known as vault grime on it. It’s kind of a dirty coin. I don’t know for sure that it came from Europe, but I’m pretty confident that it’s probably one of the coins from Europe because they typically have this vault grime on them.

On the west coast, the coins tended to circulate a little bit more. Partly this was due to the high inflation caused by the Gold Rush. In some places, you might have to pay $50 for a steak dinner, the same price you might today 150 years later. So the gold tended to circulate more out west.

Collectors Weekly: Why was the coin called a double eagle?

Dwyer: The word “double” describes its value, $20, which was double the $10 eagle. The half eagle was worth $5 and the quarter eagle was worth $2.50.

Collectors Weekly: Where were double eagles minted?

Dwyer: Well, in the beginning, 1850, it was in Philadelphia and New Orleans. So you can get an 1850 double eagle from both of those mints. Then, in 1854, the San Francisco Mint began striking coins. Shortly after the Civil War started, the New Orleans Mint went over to the Confederate side, and it didn’t reopen until 1879, when a small number of New Orleans double eagles were struck.

Collectors Weekly: What were the different types of double eagles?

Dwyer: There were two major types. One was the Liberty Head double eagle, and the other was the Saint-Gaudens. The Liberty Head was designed by James Longacre and was minted until 1907. The sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens designed the coin that followed, from 1907 to 1933.

Within these, there are sub-groups that people tend to collect. Most Liberty Head collectors prefer double eagles through 1866 without the In God We trust motto on them. After the Civil War there was a lot of religious sentiment in the country, so the motto was added. The 1864 two-cent piece was the first coin to actually have the motto on it. Double eagles followed two years later, along with some other coins.

This San Francisco-minted double eagle from 1857 was recovered from the wreck of the S.S. Central America, whose sinking hastened the Civil War.

In 1877, the Liberty Head changed again when the description of the denomination on the back of the coin was changed from “Twenty D.” to “Twenty Dollars” fully spelled out. There were other little differences on the reverse, things like the shape of the shield, but most people pretty much identify double eagles by motto versus no motto, Twenty D. versus Twenty Dollars.

I actually prefer the Liberty Head. I actually think it’s the better coin. The other one is considered by many to be the most beautiful coin we have, and I agree that it is very artistic. But to me it looks like a beautiful piece of metal rather than something I would think of as a circulating coin.

I also gravitate to the history around the early double eagles. You have the California Gold Rush, which was the whole reason for them to come into being in the first place. And you can be pretty sure that any early double eagle with an S, for San Francisco, mintmark on it is made out of California Gold Rush gold. To me, that’s exciting stuff.

There are also great rarities in the early Liberty Heads because the mintages were just so low. But it’s not just about supply—demand also plays a role. I’m not a dealer, I’ve never been a dealer, and I have no plans to become a dealer. But if you were to talk to a dealer about these, they’ll focus on the rarity and the mintage figures. The dealer will look at mintage numbers and conclude that compared to other coins, the Philadelphia double eagles from, say, 1858 are undervalued, and so you should buy them.

It’s been that way for years, and for years these same coins have always been the best value, but not if you want to sell them. That’s where demand comes in. There’s a premium on the mint. People want New Orleans gold coins. They want San Francisco gold coins. There are collectors that specialize in just New Orleans gold or focus on the mints. But you don’t hear people focusing on the Philadelphia Mint. It doesn’t have the demand that the other mints have and it never will, in my mind.

Carson City, Nevada also had a mint—the 1870 Carson City double eagle is very rare because so few of them came out. But even if you compare coins with the same rarity and mintage numbers, Carson City gold coins are always going to command a premium over Philadelphia gold coins because people want that old Gold Rush gold.

Collectors Weekly: Do minting variations make double eagles more collectible?

Dwyer: Not really. For example, there are a lot of die variations on Liberty Head double eagles, but they don’t currently command any premiums. Double eagles are not like Lincoln pennies, which are collected by millions of people.

The reverse of 1850 to 1877 double eagles read "TWENTY D." to describe the denomination. This example was minted in San Francisco in 1857.

Take the 1955 Lincoln penny with the double-die obverse: Well, some Liberty Head double eagles have that, too, but people just don’t collect double eagles for that reason because it’s too expensive. That’s not to say it won’t change in the future, but right now, variations like that don’t get much attention.

People pay attention to die variations when there are millions of collectors in the picture. As the number of double-eagle collectors grows—and I think the growth is reflected in the prices—they’re going to start differentiating by that sort of stuff.

One of the examples that I find most interesting is the misspelling of “Liberty” on the master hub, which affected every coin minted from 1850 to 1858. It was spelled “LLberty.” To correct it, an “I” was punched over the second “L” but you still see the remnants of the L below it, even without magnification.

That extra L was probably just caused by some guy who made a mistake. He punched the first L then punched the second. Then, somewhere along the line, somebody caught it. With overdates, I believe sometimes that was just caused by reusing the die. Let’s take the 1853-over-2 double eagle overdate as an example. They may have had an 1852 die but they needed 1853 coin, so they just took a 3 punch, positioned it over the 2, and repunched it.

That double eagle does command a premium, but for me, personally, I would hesitate. If I was collecting just by date, including overdates, and I had to pick a coin to leave out, that would probably be the coin that I would pick because there’s an argument as to whether or not that’s really a 2 under there or not. I’ve looked at it under magnification—personally I think the 2 is there. But what if somebody comes along one day and proves that it’s not a 2. Will the premium go away? That’s why I hesitate.

Collectors Weekly: What are some of the other causes of die variations?

Dwyer: Well, the dates could have been punched into the dies separately, and they might have had different size dates for different coins. In some cases the same punches could have been used on silver dollars that were used on double eagles. So there could have been situations in which somebody grabbed a date punch that wasn’t supposed to be on a double eagle but used it anyway, and this act created a variety that subsequently got collected.

It really comes down to The Official Red Book by R.S. Yeoman. If the variety gets listed in the Red Book, it immediately starts commanding a premium because all of a sudden anyone who’s putting together a complete set now has to have one. They’re missing it from their set. And when the variety gets listed under registry sets on PCGS (Professional Coin Grading Service) and NGC (Numismatic Guaranty Corporation), it helps perpetuate the demand.

The thing is, right now none of the double date coins are under a registry set or in the Red Book, so therefore they don’t command a premium. But if that ever changes… People do pay premiums for double dates when they are listed, so there’s a lot of hidden value out there.

Collectors Weekly: What about the platinum-sandwich coins?

Dwyer: Those were counterfeited double eagles shortly after the Civil War. At the time, the mint director had actually made a recommendation to discontinue the double eagle because it was so easy to counterfeit. Counterfeiters would simply cut the coin in half, separating the obverse from the reverse. They’d hollow it out, fill it in with platinum, and basically glue it back together. The work was done well enough to pass them off as valid double eagles. Even the weight was similar. Today it would be looked upon as a very crude attempt at counterfeiting, but in its day, it was considered quite good. Today, you’d probably like to have one of those if you could find one. I’d love to have one, but I’m sure those are all long gone.

Collectors Weekly: What are some of the major gold double eagle rarities?

Dwyer: Basically you’re talking about the first Liberty Heads from 1850 to 1866. If you’re going to collect Liberty Head double eagles, those are the most popular. They’re in a very good historical time period. There are great rarities, but at the same time, recent shipwreck finds have made lots of beautiful coins available and more affordable.

Double eagles minted in New Orleans, such as this one from 1860, are among the rarest $20 pieces around.

Within these coins, there used to be a tier of rarity from, say, $10,000 to $100,000 each, for coins like the 1855-O, 1859-O, and 1860-O, all from New Orleans. But since at least 2002 or 2003, the values on that tier have just skyrocketed. And so, even people who were willing to spend a little more are being priced out of the market. For any type of rarity, it’s strictly a high-roller game.

The next two great rarities are the 1854-O and 1856-O New Orleans double eagles. Maybe only 20 to 30 of each exist. They’re out of the reach of just about everybody now. Even one with a hole in it is going to cost you more than a hundred-thousand dollars. A nice one? You’re getting into half a million or more.

Even pricier is the 1861 Philadelphia Paquet, of which only two are known and now command prices in the millions. The San Francisco Paquets used to be at the under-$100,000 level, although some examples would go higher because the coin had a unique design to it. That came about in 1861, when Anthony Paquet was asked to redesign the reverse of the Liberty Head. One of the things he did was to make the letters taller and skinnier. But when they minted a bunch of these in Philadelphia, they determined that the dies weren’t going to be able to last, that they were going to have problems with die breaks, so they canceled the redesign and melted just about all of their coins.

In San Francisco, they had already started minting, and by the time word got out to cancel the coin, about 12,000 Paquet double eagles had already been released into the circulation. So in this case, the San Francisco coin is really the only option for collectors who can afford one. In truth, none of the Paquet coins should exist at all.

Another rare one is the 1866-S no motto, although it’s not as rare as the Paquet. There are probably 200 or so of those. Like the Paquet, the 1866-S no motto shouldn’t exist. As the year began, coins were going to be struck without the In God We Trust motto on them. Then the decision was made to add the motto. The Philadelphia and New Orleans mints got the word in time, but once again, by the time orders reached San Francisco, they had already minted a bunch of no-motto coins and released them.

Collectors Weekly: What happened to the New Orleans Mint during the Civil War?

In 1861, Anthony Paquet redesigned the reverse of the Liberty Head double eagle. The front, or obverse, shown here, remained the same.

Dwyer: Well, to me the 1861-O is one of the most fascinating of the 1850-1866 double eagles. It was actually minted by three different authorities. The first was the Union. Next came the state of Louisiana when it seceded from the Union but before it had joined the Confederacy. They hadn’t turned it over yet, although eventually they did.

This is where the shipwrecks come in, particularly the S.S. Republic shipwreck. When the S.S. Republic sank in 1865, it had almost every double eagle from 1850 on board. The only one missing was the 1856-O, which just goes to show you that the rarity was true. Also on that shipwreck was one 1854-O, which is the second rarest double eagle from that period, an 1860-O, and an 1861-O. But that 1861 New Orleans coin, even though it’s not as rare as the others, is a fascinating coin because you don’t really know who minted it. It could be a Confederate coin.

There were only 17,000 or so 1861-O coins minted. On some of the coins, you can see where the date has been reworked. Some people say, “Well, that must be a Confederate coin because they were fixing the date.” Every now and then you’ll see somebody trying to sell one of those at a premium under the theory that it’s a Confederate coin, but in my view, you should not pay a premium for this coin because nobody has ever been able to prove which ones are confederate and which ones aren’t. So, if you can afford an 1861-O, the last thing you want to do is add a premium onto the cost based on its possible link to the Confederacy, which could be proven wrong later.

Collectors Weekly: Why are the rare double eagles so prized by coin collectors?

The letters on the reverse of the 1861 Paquet were tall and skinny, making them difficult to strike, so the redesign was cancelled. But not before thousands like this one had been put into circulation in San Francisco.

Dwyer: Right now there are a lot of new collectors who are trying to put together sets, whether by mint, date, or mint. Many of these are wealthier people who have been told to diversify some of their portfolio. Rare coins have done well versus the stock market, especially in the last year. The advice these people get is to go after the rarest, most expensive coins because those are the ones that never sell for less, or at least that’s what the brokers say. This is obviously not always true but it is probably true if there are only four or five examples of a particular coin available—if the supply is that small, you don’t need very many rich people who want them to keep the price up. That’s why I think you’re seeing some of these enormous values today, where coins that were expected to go for a hundred thousand sell for half a million, and everyone is surprised.

When I was a kid, I would have never considered a double eagle for my collection. Even back then, they cost hundreds of dollars. There was no way I was going to get one. As I got older, double eagles started to get more within my price range. But it requires you to be at a certain level financially, and there’s risk involved, as with anything. The biggest risk for me is my lack of diversification. I collect 1850 to 1866 double eagles by date and mint. But if double eagles ever fell out of favor or if demand ever dropped far enough, the prices would sink like crazy. That may never happen, but things do go in and out of favor.

Most collectors only see the big, expensive, rare double eagles at auction. What they don’t see is how many times those coins have traded in private behind the scenes. So, you may look at the auction and say, “Man, this 1856-O double eagle has only sold at auction once or twice in the past five years.” On the other hand, that same coin may have traded hands two to three times in the past year. With the big rarities, some people just want to be able to say they owned one for a while. They buy it and then they sell it two years later—sometimes you see the thing come up six months later.

Collectors Weekly: Can you tell us more about the shipwrecks and gold coins on the S.S. Central America?

Dwyer: It was common to ship coins in great quantities all around the country. The S.S. Brother Jonathan and the S.S. Central America were transporting mostly newly minted San Francisco gold. The gold from the San Francisco mint had made it down the Pacific coast, across Central America, and into the Gulf side. When the S.S. Central America sank in 1857, it was on its way to New York—a hurricane sank her.

At the time, the country was in a financial crisis, not unlike what we’re in right now. Banks were failing and things like that. People started hoarding their gold and silver. In Europe, countries were demanding payment in gold, so there was lots of gold being shipped here and there. Banks in New York were running out of gold, so the gold on the S.S. Central America was terribly important. When the ship sank, the financial crisis began to spin out of control. It didn’t cause the financial crisis, but it sure poured fuel on the fire.

This New Orleans double eagle from 1861 was recovered in the S.S. Republic shipwreck. Because of the Civil War, it could have been minted by the Union, the state of Louisiana, or the Confederacy.

A lot of historians believe that this financial crisis was a big reason for the Civil War starting as early as it did. The Civil War happened for all sorts of reasons, but it may have occurred later if it had not been for the sinking of the S.S. Central America and the financial crisis that followed.

The S.S. Central America was carrying not just double eagles but also hundreds of large gold ingots and bars of gold, and even gold dust. There were unrefined nuggets on that ship. One of the exciting things about the shipwreck’s recovery is that all of a sudden you could actually buy gold nuggets that you could be 100-percent sure came out of the California Gold Rush because they were on a ship that was sending California gold to New York.

The S.S. Republic, which I mentioned earlier, was headed from New York to New Orleans in 1865 right after the end of the war as part of the Reconstruction effort. The ship contained things like school supplies for kids and all sorts of other stuff, as well as gold double eagles, gold eagles, and more than 50,000 silver half dollars.

On the S.S. Central America, there were thousands of mint date 1857-S, 1856-S, and even 1855-S double eagles, just beautiful coins that looked like they did the day they came off the presses. The water was deep enough so that the coins weren’t etched by sand, which is common to shipwrecks closer to shore, where tides and sand can ruin coins. These were pristine, mint-condition coins. All of a sudden, almost any serious collector could now afford to get an uncirculated coin for their collection.

There was also what we call passenger gold. Most passengers carried their coins in purses and on their body. If they were making a long trip, let’s say from California to New York to visit relatives or whatever, they might sew a double eagle into their clothing. One of the coins in my collection is a privately minted eagle made by Moffett & Co., which was a private mint in San Francisco before the San Francisco Mint opened. It’s a worn, circulated coin that probably saw plenty of poker games and things like that. There were a few of these scattered around in the wreck.

Collectors Weekly: How are shipwreck coins verified?

Dwyer: If a shipwreck coin has been put into a holder by PCGS or NGC, then the pedigree is pretty much assured. It didn’t always used to be that way. One of the biggest shipwrecks for double eagles was the S.S. Yankee Blade. This was in the late 1970s. The shipwreck was found, the double eagles were recovered, and then they were secretly released into the collecting population.

The S.S. Yankee Blade went down, I believe, in 1854 in San Francisco. It was racing another ship in the fog toward Mexico when it hit something and sank. The coins were in shallow water, so they were etched by sand. Some people say they shouldn’t even have been graded—that the damage from the shipwreck should’ve excluded them from being graded and put in the holders.

In fact, when you submit a coin to a third-party grading company, if it has been harshly cleaned or if there’s some damage on, maybe a big scratch, the company will send it back to you saying, “Sorry, we couldn’t grade it. It’s damaged.” Some grading services will send it back and say, “Well, if it wasn’t damaged, it’d be this grade,” and they’ll list the damage on the holder. With shipwreck coins, companies like NGC will note the shipwreck effect on coins that are damaged enough that they can’t be graded.

Coins such as this 1861 New Orleans double eagle survived more that a century at the bottom of the sea thanks the deep depth of the wreckage site and way in which the coins were packed tightly together.

A lot of people, though, say that since all these shipwrecked coins have damage on them, they shouldn’t be put in holders at all. By that logic, there are thousands of mint date coins that shouldn’t exist because they’re all technically damaged. But that is obviously not true since thousands of S.S. Central America coins have been cracked out of their holders and resubmitted in an attempt to get a higher grade, thereby losing their shipwreck pedigree. Still, a lot of collectors like the shipwreck coins, which actually command a premium if you’re trying to buy one in the same grade as one without the shipwreck designation.

The conditions of the wreck are the key. Obviously many of the coins on the S.S. Republic were damaged when the ship broke apart, but many others were intact and stayed sandwiched together, which protected them. Over time a sea crust formed over them, and it turns out that that protected them, too. The same thing happened with the S.S. Brother Jonathan coins. When they were found, there were still a lot of them stacked in their wax paper wrappers and encrusted by sediment. It was like they had been sealed in cement and protected for a hundred years.

It didn’t used to be this way with PCGS or NGC guaranteeing the pedigree. It used to be that when you bought a shipwreck coin, all you’d get with it was a certificate. There was no encapsulation or anything like that—your only assurance that it was from a shipwreck was a piece of paper. Well, how do you know that piece of paper is real? On eBay one time, I actually saw an auction for shipwreck certificates, without the coins. Where’s the guarantee in that?

So I won’t touch an uncertified shipwreck coin. I love them, but I won’t pay a premium for a coin that’s not certified. If it’s the same price as one without the shipwreck pedigree and I’m pretty sure it is a shipwreck coin, I might buy it as a shipwreck example. But I won’t pay a premium for a shipwreck if it’s not encapsulated.

Collectors Weekly: Are there any double eagles that were actually illegal to own?

Dwyer: In the 1950s, a 1933 double eagle was put up for auction, confiscated, and then eventually went to auction anyway. Here’s how it happened. In 1933, when Roosevelt became president, one of the first things he did was to make it illegal to own gold—it wasn’t until just a few decades ago that it became legal again to own gold in the United States. The only gold that wasn’t confiscated was gold that was considered to have numismatic value, and that was left very vague. Well, in 1933 the new double eagles were set to come out. Obviously they were not going to have numismatic value because they were slated to be the current circulating coin. So they were all supposed to get melted down. Naturally, some of them didn’t.

One of the biggest coin collectors in the first half of the 20th century was King Farouk of Egypt. After he was deposed in 1953, the new government auctioned off his collection, including one of the 1933 double eagles. When it was listed for auction, the U.S. said, “Hey, that coin is illegal, we want it back.” Egypt and the U.S. were not getting along at the time, so instead of giving it back, they just pulled it from the sale and the coin disappeared. Eventually it reappeared in England, there were lawsuits, and finally the U.S. and the guy who owned it worked out a deal to auction the coin and split the proceeds.

Collectors Weekly: If you could own just one double eagle, which one would it be?

The San Francisco Mint struck its first double eagles in 1854. This coin, whose gold came from the California goldfields, was recovered from the wreck of the S.S. Republic.

Dwyer: Out of all the rare double eagles—the 1933, the 1856-O, the Paquet—if I had all the money in the world and I could buy any one I wanted, I would actually get one that isn’t even in any of the reference guides. It’s not a great rarity as far as the date and mintmark. But it’s a double eagle that was in the pocket of Confederate Lt. George E. Dixon, who went down in the Civil War in the submarine, the H. L. Hunley. This coin was in Dixon’s pocket.

There had been a legend about this coin for more than a hundred years. According to the story, Dixon had a coin in his pocket that he had carried with him at the Battle of Shiloh. During that battle, the coin took a bullet direct in his pocket—if the bullet had missed the coin, it very likely would’ve killed him. When they found the wreck of the H. L. Hunley a few years ago, they found this same coin in his pocket, bent from where the bullet had hit it, and engraved with the date of the Shiloh battle. So a legend that seemed unbelievable turned out to be true. You couldn’t get it graded because it had been shot with a Civil War musket, but to me, that is the coolest double eagle.

Collectors Weekly: Can you suggest some double eagles for novice collectors who just want the pleasure of owning one?

The reverse of the San Francisco 1866 double eagle, the last coin put into circulation without the In God We Trust motto.

Dwyer: Yes. The 1861 Philadelphia is the most common double eagle—almost 3 million were minted. The 1854-S is the first double eagle struck in San Francisco, but there’s a bit of a premium on those, so you might have to settle for a lesser grade. But that may be okay: I actually like some of the used, circulated coins because it’s nice to know that it didn’t just sit in a bank vault prior to sinking in a ship—that it was in somebody’s pocket or in a saloon or used for gambling. But if you want a high-grade California Gold Rush coin that’s still affordable, you can go after an 1857-S from the S.S. Central America shipwreck, because in 1857 it was still California gold.

The first time I ever held a double eagle in my hand, the thing I liked the most about it was that it was a nice, big, heavy coin. It’s like the Morgan silver dollar. They’re similar in size and I like those silver dollars because they’re big. It’s why people collect these things versus dimes. The fact that it’s gold makes it that much better, and the fact that there is all this history in these coins—the shipwrecks, the Civil War, the Gold Rush—well, you just can’t write a better story for a coin.

(All images in this article courtesy A.C. Dwyer of acdwyer.com)

During the Civil War, Some People Got Rich Quick By Minting Their Own Money

During the Civil War, Some People Got Rich Quick By Minting Their Own Money

An Interview with Smithsonian Coin and Currency Curator Richard Doty

An Interview with Smithsonian Coin and Currency Curator Richard Doty During the Civil War, Some People Got Rich Quick By Minting Their Own Money

During the Civil War, Some People Got Rich Quick By Minting Their Own Money U.S. Pattern Coins Tell the Stories Behind Our Currency

U.S. Pattern Coins Tell the Stories Behind Our Currency US Ten Dollar Gold CoinsThe U.S. $10 gold piece (or 'eagle') was one of the first American gold coi…

US Ten Dollar Gold CoinsThe U.S. $10 gold piece (or 'eagle') was one of the first American gold coi… US Five Dollar Gold CoinsThe US five dollar gold (half eagle) coin was one of the first American gol…

US Five Dollar Gold CoinsThe US five dollar gold (half eagle) coin was one of the first American gol… US Twenty Dollar Gold CoinsWhen the California Gold Rush made the United States a wealthy country almo…

US Twenty Dollar Gold CoinsWhen the California Gold Rush made the United States a wealthy country almo… US Two and a Half Dollar Gold CoinsThe US $2.50 ('quarter eagle') gold coin was issued in 1796, and was the fi…

US Two and a Half Dollar Gold CoinsThe US $2.50 ('quarter eagle') gold coin was issued in 1796, and was the fi… US One Dollar Gold CoinsThe first one-dollar gold coin was issued in 1849, more than half a century…

US One Dollar Gold CoinsThe first one-dollar gold coin was issued in 1849, more than half a century… Gold and BullionAccording to the National Mining Association, gold was first excavated in w…

Gold and BullionAccording to the National Mining Association, gold was first excavated in w… Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

I have had trouble finding the gold content of U.S. coins of around 1890-1900. I have a few which I bought just because I like antiques, gold and money. Not interested in selling them, just curious.

I am not really into collecting coins, but enjoy reading about the history of coins. I was given several $20.00 double eagles only one has the ( s-mint 1904) the rest do not show a – mint. Were these minted in

Philadelphia? Thanks for any info.

Sirs,

I have been a coin collector for about 45 years, mainly British coins. I have a friend whose brother found a coin, USA 20 Dollar 1849 double headed eagle. They have asked me if I can find out anything regarding this coin. I have photographs of it and it appears that this coin is not gold. The coin was found on a building site in the Philippines which was formally a US military sit during the 2nd world war. It has more than average wear. What I would like to know is if this coin could have been a genuine coin struck as sample before the gold version was made. Or is it just a fake.

Would appreciate your comments. Gordon Long

Hello,

I have double eagle coin from 1904,wat is in an excellent state .

i would like to know wat is the value of this coin as they told me that this year has a big value .

This coin has been minted in Carson City, San Francisco, New Orleans, Denver

Thanks for any Info

I see there are a few questions about gold coins so I thought I’d give some answers.

Freida: U.S. gold coins of the 1890-1900 time period were 90% gold and 10% a copper/silver alloy. A $20 gold double eagle contains about .967 ounces of pure gold. A $10 eagle would be half of that. You can see the pattern to basically figure out the smaller denominations. So if the spot price of gold were at $1,000 (it’s actually higher right now), then a $20 double eagle would contain just under $1,000 worth of gold.

Doyle: Yes, the $20 double eagles without a mint mark were minted in Philadelphia. The mint marks are as follows: CC = Carson City, O = New Orleans, S = San Francisco, and D = Denver.

Gordon: The 1849 $20 coin is undoubtably a fake. Double eagles did not begin being minted for circulation until 1850. A few 1849 specimens were created with only one known to still exist. This coin is currently at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. If your coin were real, it would be worth well in excess of $10 million.

Celine: Your 1904 coin would have been minted at either Philadelphia or San Francisco as those were the only two mints that produced double eagles that year. In either case, the 1904 from either mint was among the largest mintages and therefore the most common of any date. Unfortunately that means the coin is worth the least of any $20 double eagle. However, the coin is not cheap and the gold content alone is worth over $1,000 at today’s prices.

I have an 1834 5D gold coin in fair shape. All words can be read easily as well as the date and there is no mintage mark, making it from Philadelphia. Is it worth more for the gold content, or as a collector’s item? Thanks, REB

Robert: If it’s real and in good condition, it almost certainly is worth more as a collector’s item, but it is hard to know just how much without actually seeing what the coin looks like.

There are two types of 5 dollar gold coins for that year, the Capped Head and the Classic Head. The Capped Head is pretty rare and even in poor condition is worth over 5 figures. The Classic Head is more common but in good condition is still usually worth at least twice its weight in gold.

Also, there are two varieties for both types of the coin, the plain 4 and the crosslet 4. The variety is determined by the numeral 4 in the date.

If you have a rare Capped Head coin, which 4 you have usually doesn’t matter. Both varieties of the 4 tend to be equally rare and sell for similar prices.

However, if you have the more common Classic Head it does make a significant difference. The crosslet 4 variety is generally worth about 4 times more than the plain 4 variety.

Post a picture of the coin in the Show & Tell area of Collector’s Weekly if you want to find out which one you have. Put it under Unsolved Mystery.

Robert:

Here are some links to coin images that can help you identify which type of coin you have. Just copy the web addresses into your browser to see the coins.

The first is a 5 dollar coin of the Capped Head type:

http://acdwyer.com/1820_halfeagle.aspx

The second is a 5 dollar coin of the Classic Head type:

http://acdwyer.com/1836_halfeagle.aspx

This third coin is a 5 dollar coin with a “plain 4” in the date.

http://acdwyer.com/1843_halfeagle.aspx

Imagine a vertical line drawn across the right end of the horizontal stem on the plain 4 and and you get the idea of what a “crosslet 4” looks like.

I hope this helps. Or post an image on the Show & Tell if in doubt.

My friend in Indonesia found two double eagle gold coins (twenty dollar coin)from his late father belonging, one was issued in 1898 and the other one in 1900. He wants to know how much are the value for those coins?

Debra:

If the coins have been circulated (used), then they are currently worth about 5-15% more than the price of an ounce of gold.

If they are uncirculated, then they could be worth from 5-15% more than the price of gold, to as much as $100,000 depending on the coin’s condition and mint mark.

Here’s what you need to look for:

On both coins, check the reverse (back) of the coin. Just below the eagle’s tale feathers (6 o’clock) there will either be an “S” or there will be nothing. Once you’ve done that, check each date in a price guide.

Here’s a link to a price guide that can help give you an idea of the values possible:

http://acdwyer.com/pcgs.aspx

Under “Gold Coins,” click on “Liberty Head $20.”

Two things to keep in mind. The higher values are really on the uncirculated coins, and then only if the uncirculated coins have a minimal amount of marks on their surfaces.

Also, the 1898 WITHOUT the “S” mint mark is the more valuable coin than the one with the mint mark. However, the 1900 coin is the opposite. The coin WITH the “S” mint mark is the more valuable.

It’s “DOUBLED-DIE” and not “DOUBLE-DIE.”

I only read through this interview once real quickly after it was posted and I guess I just wasn’t paying close attention.

In the parts of the interview where we talked about die varieties, the term “double-die” comes up a few times. This should actually have been transcribed as “doubled-die.”

It may sound pretty insignificant to leave the “d” off the end, but I learned many years ago that it makes a world of difference to my fellow numismatists.

I remember years ago I wrote an article for a popular coin publication and I accidentally left off the “d” in one of my references to a doubled-die. Boy you should have seen the scathing message I got back from the editor. He let me know that if I did that even once, it could cause me to lose all credibility among my fellow numismatists.

So please remember, it’s “DOUBLED-DIE” and not “DOUBLE-DIE.”

hello AC.. i have from my family.. A 1908 20$.A 1910 5$. A 1881 five D with a s in the back, and a 1853 1$.. I would like to know if i need to look for any rarities on then or so.. and whats the value of them..i could post pictures ..please let me know thanks.

Ben:

You should definitely post pictures of your coins in the Collector’s Weekly Show and Tell area. It sounds like you have a nice group of coins there. If your family has held the coins for awhile, then regardless of condition and rarity, you’ve done pretty well as an investment just from rising gold prices in recent years.

As to whether or not there is any numismatic value above the gold content, it’s really all about the condition of the coins and the rarity. Unfortunately, none of your coins are very rare, but let’s take a quick look at the possibilities:

1853 $1 – I’m assuming that this is a gold dollar and not a silver dollar. The gold dollar is one of the most common with over 4 million produced. Circulated examples run from a couple of hundred dollars to few hundred dollars. If it’s uncirculated, it could range from a few hundred dollars to a couple of thousand. However, if it is actually a silver dollar, then it is a different story as nice examples of the silver dollar can be worth much more than the gold coin.

As for the 1908 $20, 1910 $5, and 1881-S $5, these are common enough that they tend to be priced like bullion coins in circulated grades. In other words there is very little numismatic value and their prices really reflect the current price of gold. However, in uncirculated grades, these coins can command a numismatic premium that can quickly double or even triple their value, especially the $5 half eagles.

When checking the current price of gold, keep in mind that the $20 coin should be close to the spot price for 1 troy oz. of gold. The half eagles would be about 1/4 of this price. Also, these would be the minimum values of well circulated coins. There is some numismatic value with these coins, so as their condition goes up, so too does the value of the coin.

If your coins are circulated examples, they make great gold investments. If you believe the price of gold is going higher in the future, then these are a good group of coins to hang onto. If you believe gold has peaked and is going lower, then you would want to sell since the value of these coins would go down as well.

If you’re in doubt about whether your coins are circulated or not, whatever you do, DON’T CLEAN your coins! Even simply wiping them with a cloth can quickly knock $1,000 or more off the value of an uncirculated example losing any numismatic value. Never clean your coins unless you are an expert at it.

I hope this helps. Please post pictures of the coins in the Collector’s Weekly Show and Tell area. I’d love to see them.

I own an 1843 O $2.50 gold coin that has been slabbed by ANACS as AU58, with SEA SALVAGE details. I would like to think that it is one of the coins that got away from the discoverers of the SS New York ship wreckage, since I see where 17 coins of this year and mint were graded by them and sold at auction by Stack’s. I know it’s virtually impossible to find out where it came from; however, surely, it didn’t just fall out of someone’s pocket when they were deep sea fishing (LOL)! Just curious as to what this coin might be worth and if there is any interest (except for me) in such coins. Your time is greatly appreciated. Thanks so much.

JoAnn:

The 1843-O $2.50 gold quarter eagle has the highest mintage of any New Orleans quarter eagles making it one of the more common from this mint. However, there are two significant varieties for this coin: a small date variety and a rarer large date variety. In higher grades, there is a significant premium on the more rare Large Date variety. Since you didn’t mention otherwise, I am assuming that your coin is of the Small Date variety.

While there is the possibility that your coin came from a shipwreck other than the SS New York (there was at least one 1843-O $2.50 recovered from the SS Central America shipwreck), the most likely scenario is that yours came from the SS New York.

There were actually 18 1843-O $2.50 coins graded by NGC from the SS New York shipwreck. It appears the additional coin missing in your total is a Large Date variety of which only one was recovered.

NGC will only grade shipwreck coins by their normal grading scale if they do not show significant evidence of saltwater exposure. Since your coin does show saltwater exposure, you can rule out it being one of these 18 coins.

However, according to Q. David Bowers there were at least three additional 1843-O $2.50 quarter eagles recovered from the SS New York shipwreck with “AU Details” that were encapsulated by NCS. My opinion is that your coin is likely one of these three, but it’s now in an ANACS holder.

Here’s what I think happened to your coin (although this is pure speculation). Since being in a NCS holder would significantly lower the numismatic value of the coin since it’s officially a problem coin, I think it was cracked out of its holder and submitted to ANACS for a grade. Since NGC and PCGS have graded thousands of shipwreck coins, they’d be more likely to catch a coin with a “shipwreck effect.” So ANACS might be a better choice to try and get the coin graded without the shipwreck details.

The reason to get the coin graded without the shipwreck details is that the numismatic premium of the coin graded AU58 is higher than keeping the shipwreck pedigree with the problem details. An AU-58 grade without the shipwreck details would cause the value to jump from a few hundred dollars to closer to $1,000 (a large date variety would be considerably more).

ANACS obviously caught the shipwreck effect. Since ANACS was the first major grading service to grade and encapsulate “problem coins,” the coin at least now had a “details” grade of AU-58. Unfortunately, it still kept the “sea salvage” details, and lost the pedigree to the specific shipwreck.

So now instead of having a shipwreck coin with a pedigree to a historical shipwreck, what you wind up with is a saltwater damaged coin without that pedigree. Unfortunately, I would think any premium from the shipwreck was wiped out during this crossover.

It’s hard to estimate values without seeing a coin, but I believe if you were to sell your coin at auction today, the coin might sell for about $200 (not including any buyer’s premium). Since the coin contains a little less than an 1/8th of an ounce of gold, this would be a slight premium to the current price of gold.

So going forward, the price of gold will be a major factor of whether or not your coin increases in value. If you believe the price of gold is headed up, keep the coin. If you think gold is headed down, sell the coin.

So overall, I do think it is likely you have a SS New York coin although you can’t prove it. If you ever sell the coin, I would mention the probability of it coming from the shipwreck. Maybe it will help the coin to sell.

None other than the reknowned Q. David Bowers has done this with 1854-S $20 gold from his personal collection that was reportedly recovered from the SS Yankee Blade shipwreck. The only evidence on his shipwreck gold was the 1854-S and saltwater etching. His belief is that all 1854-S $20 gold with saltwater etching must be from the SS Yankee Blade. In other words, the SS Yankee Blade shipwreck pedigree was all speculation, but it didn’t stop him from suggesting the connection when it came time to sell.

I have a 1883 S Double Eagle – San Fransisco Mint $20 gold coin. It is a little warn, however I feel it is in good condition. I am just curious what it would be worth.

Faye:

The 1883-S is one of those double eagles that is old, but still common enough that it basically sells as a bullion coin. Since there is a little less than an ounce of gold in the coin, you could expect to get close to whatever the going rate is for an ounce of gold. Maybe a little more for a really nice example.

Hi! I have a question I would like to ask about a 1879 $5 Half Eagle liberty head coin. On the back of the coin, the eagle has a ribbon with motto overhead, with three arrows in his right hand and a leaf in his left. His head faces to the left and has no mint mark. So from what I have read so far, I think that means it was minted in Philadelphia? This coin was originally my great grandmother’s, passed on to my grandmother, to my uncle and then to me in 1989. This coin has been safely keep in a coin holder and has been in a safety deposit box for at least the past one hundred years, so it has very little wear on it from what I can tell. Would you be able to tell me what grade you think this could be? Also when my uncle got ready to pass this coin on to me, he took it to a jeweler and had a detachable and reatachable beautiful gold necklace brace put on it so it could be worn as a necklace. The brace was for coins and it can be removed easily by just twisting a tiny little screw on the top of the holder. Will that hurt the value of the coin? It is very easily removed and it was never worn. Really, long story short, I would really appreciate any info, tips, or advise you could give me about this piece. Thank you very much for your time!

Sincerely,

Natalie

@ Natalie

The good news is that with the price of gold at close to $1,500 an ounce, your coin is worth at least about $400 even if it had been well circulated. The bad news is that there is not much of a numismatic (coin collector) premium since the coin is considered a common date coin.

However, if the coin is uncirculated (no sign of wear and tear), then the coin’s value could quickly rise into the thousands depending on its condition.

Condition is everything and a lot could have happened to the coin even though it was mainly kept in a safe deposit box. The fact that the coin appears to have been worn as jewelry leads me to believe the coin will be in a circulated condition. Even though you don’t think it was worn, it only takes someone wearing it once to put the coin into a circulated condition. Plus the jewelry holder could have damaged the edges of the coin. So keep your expectations low so as not to be disappointed.

I think the best thing you could do is go to a local coin show when one comes along and let “multiple” dealers look at it. Or take it to a local coin club and ask their members what they think. You are more likely to get an honest opinion from them. But very carefully take it out of the jewelry holder before you show it to them. Make sure you hold the coin by it’s edges and whatever you do, don’t clean it!

Or if you have good photos, post them here on CollectorsWeekly in the Show and Tell section under Gold Coins. If you remove the jewelry holder, then post photos of it as well. It’s best to get as many opinions as possible.

I just got an 1846-O $5 gold gold coin back from NGC in a body bag that says altered surface. I am guessing it would grade around AU-55-Au58 details. The coin has a rough texture similar to some of the Indians I have owned in the past, but does have some rough places in the field. I am not a coin grader, but wonder what the odds are of this being a saltwater damaged coin, and where can I find out. They did mark it as genuine, although on first appearance I feared it was a cast copy, it has that look.