In part one of our interview with her, Merikay Waldvogel talks about the history of American quiltmaking (see also part two on Collecting American Quilts). Waldvogel is an internationally known quilt historian, lecturer, and author. Among her books are “Quilts of Tennessee: Images of Domestic Life Prior to 1930” and “Soft Covers for Hard Times: Quiltmaking and the Great Depression,” which is regarded as the key work on mid-20th century quilts and quiltmaking. She is on the board of the Alliance for American Quilts and the American Quilt Study Group, and is a fellow of the International Quilt Study Center at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. In May of 2009, Waldvogel was inducted into the Quilters Hall of Fame.

I always wondered why I was so fascinated with the quilts. In the early 1980s, when I was the executive director of the Knoxville Women’s Center, I was getting into women’s issues and women’s employment, and, at the same time, I was drawn to something handmade, traditional. Quilts really changed the direction of my life, and here I am at retirement, grateful for what quilts have added to my life.

Quilts were my entrée to the South, the history of the South, and, in particular, the Civil War. In the 1950s, when I was growing up, I can’t remember really being taught much about the Civil War, but it’s an important time period to understand. And I learned about it through a different point of view, through the quilts and the women who made it.

I needed to know how war impacted families, the kind of cloth that was available, what they were doing with the cloth, how they were treating and saving the quilts. I met a woman named Bets Ramsey, who was known as the quilt lady of east Tennessee. I invited her to come to speak at an event at the Knoxville Women’s Center. We invited people to bring their quilts to show us; we wanted to hear their stories. And we got probably 50 quilts on a Sunday afternoon. That was, I think, 1979.

Bets and I became very good friends. She and I became co-directors of the Tennessee Quilt Survey. A similar survey had been done up in Kentucky in 1980 and ’81. We decided we wanted to do that in Tennessee. We wanted to see more quilts. We wanted to hear the stories. We wanted to provide the owners with information on how to take care of their quilts and keep their quilts safe and clean.

Collectors Weekly: Was this how your first book came about?

Waldvogel: Yes. Our goal was to do an exhibit and a book. We had a cutoff date of 1930. Now, this was in 1984, ’85. The 1930s quilts weren’t considered antiques yet. We went all over the state, and then chose 32 representative quilts and asked the owners if we could borrow them for the exhibit. The exhibit traveled around the state in 1986 and ’87. We wrote a book, which came out in 1986, called Quilts of Tennessee.

My name started to appear in newspapers. People began to ask me to write things, to come speak. There were quilt guilds forming all over the United States, and they always needed somebody to give a talk on quilt history or antiques. So that’s how we started out. We’re members of the American Quilt Study Group, which is a national organization originally based in Mill Valley, California. So I went to California a lot for meetings. I ended up being on that board when it was in San Francisco.

I began publishing other books. After Quilts of Tennessee came out, both of us, Bets Ramsey and I, realized we had probably made a pretty serious mistake by not including 1930s quilts because the women who had made those quilts were still alive in the 1980s.

Around 1987, the Knoxville Museum of Art asked me to do a book and a project and exhibit on depression-era quilts that would travel around the country. And although I personally wasn’t collecting them, I took it as a challenge to find out why the quilts of the 1930s don’t look dark and bleak like the times in which they were made. The book, called Soft Covers for Hard Times: Quilt Making in the Great Depression put my name on the map because it was the first fully fleshed out book about quilts of the Depression. It wasn’t just about rough-and-tumble feed sack quilts, utilitarian quilts. It was also about the marketing of quilts, the distribution of quilt patterns across the country in newspapers, quilt contests, and the Colonial Revival style in quilts during the Depression.

Collectors Weekly: How did the Depression affect quiltmaking?

Waldvogel: The Depression made people hunker down and band together. Families didn’t move around as much. Some people who were unemployed went back to their country homes, lived with their families. Quilt making and being resourceful struck a chord in the minds and hearts of the people living through it. Some of them remembered the Depression of the late 1800s, the Civil War years, times when they had to deal with reduced resources, hard times, even scary times. They were proud of being able to make something with their own hands, of being resourceful, using what was at hand. I think that was reflected in the 1930s. I tried to bring that out in the book.

One of the chapters in that book was about the 1933 Sears quilt contest. And that became my third book, Patchwork Souvenirs of the 1933 World’s Fair. The 1933 Sears contest was something like Powerball today. They were offering a thousand dollars for the best quilt, and 24,000 people entered that contest. It’s still the largest quilt contest ever held. The sad part about that whole contest is that the woman who won the grand prize hadn’t sewn a stitch. It was a scandal involving the judges and that woman.

A lot of people were very disappointed, and it became a story that quilt historians have always wondered about. And so Barbara Brackman and I decided to track down that story, track down some of the people who made those quilts. It’s a very personal reflection of what was going on in those people’s lives in 1933. Later, I wrote a book about Civil War quilts called Southern Quilts: Surviving Relics of the Civil War. My latest one is on doll quilts, Childhood Treasures. So that’s where I am.

Collectors Weekly: What techniques and patterns were used during the 1930s?

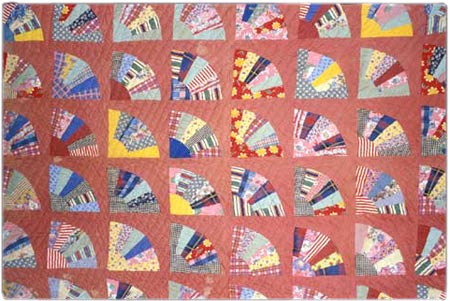

Waldvogel: Depression-era quilts, I think, can be divided into ones made from patterns that were published in newspapers and quilts that were made the old-fashioned way. Let’s talk about the ones that were made the old-fashioned way, the Colonial Revival way, for example. There’s something called the string-quilt technique, which is basically a crazy-quilt technique. You start with a piece of newspaper, let’s say it’s 12 by 12 inches. You take scraps of cloth, feed sacks, anything, and you just sew strips of cloth from those scraps to the newspaper. After you clip the little ends hanging off the sides of the newspaper, you end up with a cloth-covered piece of newspaper. Make a dozen of those and you can put the top together and quilt it. You don’t see patterns for that kind of quilt. People just learned to make quilts like that. You made them fast. You’re putting fabrics together without a sense of the pattern.

This “String Quilt” from the early 1920s, by Alice Ramsey Huskey, is based on a common pattern called “Ozark Tile.”

So let’s put that technique aside and look at the newspaper patterns, in Knoxville, for example. There were two or three newspapers here. One newspaper carried the Laura Wheeler column two or three days a week. Each column featured an illustration of a quilt and a very small description underneath it. And if you wanted to buy the full pattern, you sent 10 cents to New York and they’d send you the full pattern. Well, a lot of women just looked at that illustration in the newspaper and made quilts from it. And so that company had to come up with patterns that would be attractive over the long term to keep their audience.

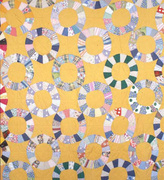

I liked that column. It reflected, I think, what was going on in the ’30s. They understood their audience. They knew that their audience probably would relate to making a quilt together, making a quilt from scratch, and they gave them some patterns that they could easily draft themselves, without ordering it. Other companies sold appliqué patterns. A newspaper might focus on appliqué patterns for a while and then take up pieced patterns. Sometimes people would take an old pattern and they would rename it—Shoe Fly or Hole in the Barn Door, it was all the same pattern. Grandmother’s Flower Garden is a traditional pattern, and in the ’30s it was called Martha Washington’s Flower Garden. See, there’s a reflection of the Colonial era. Thousands of new patterns came into the melting pot of patterns during the ’30s.

The dress fabrics that were being sold were in pastel colors—pinks, blues, yellows, oranges— and very fine, small prints. They were really nice fabrics. You did not see brown or black, or dark green. You might expect to see those colors in the Depression, but they just weren’t there. I think the fabric companies were selling bright colors because it was a way to take people away from thinking about the situation they were in. And if you were making clothes from those bright colors and you had fabrics left over, you could cut them up and use the scraps in the string quilts I was talking about earlier.

If you had a little bit more money, you could buy a kit that contained all the fabric cut into all the shapes that you needed to make your quilt. So, for example, if it was a big star quilt which takes hundreds of diamonds and all of those different colors, the fabric company would not only cut all those diamonds for you, they would sort them by colors so you could put together your star, just hand-piece it together. And all of that would usually cost $2. Or you could buy an appliqué quilt kit and, again, it would be less than $3. Inside the box was the white background fabric, stamped where you’re supposed to place the different colors—even the quilting lines were on there. It was like paint by number. But even that was too expensive for some people.

The 1930s had it all, I think, because the marketers, the magazines, the newspapers, and the thread companies realized that women were going back to crafts, going back to handwork. They provided a lot of patterns, shortcuts, and lively fabrics. What came out and what we remember about Depression-era quilts is that there were a lot of them made and they all have a similar color range. It’s pretty easy to tell which ones are which.

Collectors Weekly: How many different styles of quilts are there?

Waldvogel: You could basically break it down into pieced quilts, appliqué quilts, whole-cloth quilts, and crazy quilts. And then beneath all those are patterns and formats. So then it becomes tens of thousands of permutations. That’s the beauty, I think, of making quilts. There’s really no end. There’s always room for originality. The focus of 21st-century quilt making are the art quilts and the pictorial quilts, the message quilts, the quilts with humor, the quilts made for some kind of project, like the valor quilts or the AIDS quilts. All of those have roots in early quilt making.

There were art quilts in that 1933 quilt contest, but the judges didn’t know what to do with them so they were put aside. There were crazy quilts and art quilts made in the late 1800s. It evolves, the quilt making tradition, the kinds of quilts, the styles, the colors. I don’t see any end to it. I think it’s still a rich area to collect in, a rich area to participate in as far as making and selling them. A lot of industries have grown up around quilt making. The rotary cutters, all the rulers, the fabric, kits, all the contests, all the events that are held nationwide, it’s a several-billion-dollar industry.

The only thing that’s suffered a bit is the print media. There aren’t as many quilt magazines as there once were. But I think there are still as many quilt books being printed, the how-to and instructional books. Quilt history books are not coming out. We should do more of those, but they’re not as popular as they were back in the 1980s.

Collectors Weekly: You mentioned crazy quilts. Can you tell us a bit more about that?

Waldvogel: The crazy quilt was made from about 1880 to 1910. The format of a crazy quilt looks like it’s broken, like broken pieces of, say, china. And that’s where the name came from, the crazes on a piece of china, where it looks like it’s cracked but it’s not. In the early years, those odd-shaped pieces of fabrics used in crazy quilts were velvets, silks, taffeta, and ribbons, and they would attach these pieces to a base fabric. Let’s say the base piece is about 12 inches by 12 inches. So you could really work on this project in your lap or at a table, and you attach these various pieces. And then you embroider over the edges of all those pieces; you could get instructional booklets on dozens of embroidered designs. They’re called edging designs. So you finish one little, maybe, 12-by-12-inch block. You make another and another and another. And finally you might do 9 to 12 of those blocks. You join them together to make a top.

In a way, it looks chaotic, but there are ways to control it. And one of the ways, I think, is to keep it to that same size of block. Sometimes you just joined blocks one to the other or you could put borders around each one of the blocks and then a border around the full quilt. And again, you might add embroidery on the borders. The crazy quilts lent themselves to collections of commemorative fabrics. And ribbons, like a souvenir from a fair or a Civil War reunion, would be put in there, too. Crazy quilts were great places to preserve a piece of your wedding dress or a piece of Johnny’s baptism gown.

This crazy quilt from the late 19th century, by Clara Graf Lederer Stanton, features a profusion of embroidery in cotton and chenille thread.

Some people stitched their names on crazy quilts, others dated them. So no two crazy quilts are alike. In a way, they are original designs. There were booklets with pretty precise instructions on how to make crazy quilts and even how to layout the blocks. They were for people who had a hard time being creative, but still you never see two crazy quilts alike.

Also, I should say that it’s a rare crazy quilt that actually gets finished. And it’s even a rarer crazy quilt that was used on a bed. For most crazy quilts, I think people got tired of the project. It was very tedious and they just left them either as single blocks, or they might have gotten the top together but they didn’t go ahead and finish it. And some of them are small, and they are made for draping over a piano or draping over a chair. They are just too fragile to put on a bed. And in that way, I think, they really were the art quilts of the 19th century. The crazy quilt format is very popular today because it’s collage-like. I think today’s contemporary quilters love the collage aspect of crazy quilts.

As the years went on, into the 20th century, the fad spread across the country. You began to see people making them in remote areas that didn’t have access to silks and velvets. They started using cotton and wool, suiting fabrics, pants fabrics. And then also as the years went on, people didn’t adhere so much to the 12-inch-by-12-inch block. Sometimes they’d make bigger blocks. Sometimes they would make them in strips, but it’s still a crazy quilt. And they still had embroidery on them, and they often had names and dates on them.

There are some pretty amazing crazy quilts that have ended up at the International Quilt Study Center. If you go to their website, quiltstudy.org, you’ll get their catalog of all their quilts and then just search. Some are just gorgeous, but we don’t know the names of the women who made them. A lot of the quilts that ended up in that museum were collected on the antiques market, without the provenance. That’s been the challenge of the graduate students at the University of Nebraska, to try to learn more about those quilts. And they have. They have a really good genealogist among their graduate students.

Crazy quilts didn’t fit into the traditional format and styles of quilts. They were unusual. They were bizarre. And that’s why they died out. Some people were still making them in the 1920s, but the stitches weren’t well done. As the crazy quilts went out, about 1910, there bloomed a new 20th-century style: a quilt with a white background and beautiful appliqué flowers. Those were Marie Webster’s quilts. She revived the format of 19th-century quilts—a center medallion and borders around the quilts. They were decorative, handmade, and looked really different than crazy quilts and 19th-century pieced quilts.

Collectors Weekly: Are Webster’s quilts considered part of the Colonial Revival movement?

Waldvogel: It’s a misnomer, that term Colonial Revival, because the quilts that came out during the Colonial Revival period at the end of the 19th century didn’t necessarily look like Colonial quilts made during the 1770s. But there was an idea or a mystique about the early days of our country, and I think that mystique involved high four-poster beds, women in long gowns, and quilts with white backgrounds, often appliqué, with flowers and birds on them. So to that extent, Marie Webster’s quilts reflected that. But she put a modern stamp on her quilts because they also had aspects of Art Nouveau and even Art Deco.

The difference from the crazy quilts was so stark. Crazy quilts were not, at this point, considered beautiful. And you couldn’t use them. They were almost frivolous and they were garish. We need to remember that there were other kinds of quilts being made at the same time as crazy quilts. I would call them utilitarian quilts, and they were very simple pieced quilts in designs, like nine-patch and tumbling-blocks and star quilts. And sometimes they were just two-colored quilts like red and white, or blue and white, or gray and white. They were the quilts that people made and used in their homes. The Colonial Revival quilts were more sophisticated than that.

Within the Colonial Revival theme, the idea of being resourceful, hardworking, clean, and family-oriented carried on. The utilitarian quilts of the day really fit more with that attitude. And so, as the quilt revival really took hold in about 1930, there were two things going on—Colonial Revival and resourcefulness. Quilts went back and forth between those two impulses. You could make a pretty appliqué quilt or you could make a traditional pieced quilt.

Collectors Weekly: When did quilting as a group activity for women become popular?

Nan Hurst is thought to have stitched this star quilt together in the early part of the 20th century.

Waldvogel: I think there was always an aspect of that. There were always people quilting at home alone or maybe with their daughter or mother, but, at the same time, there were quilting parties. Maybe somebody would just offer their finished quilt top as an opportunity to get together. There was always food. There was always a good chance to talk. They weren’t called quilting bees. In our area, they’re called quilt-ins. It was an opportunity to get together and quilt. It often happened in a church.

In the 1930s, some of the home-demonstration agents were purposely trying to get women together not only to quilt, but when they got them together, they would also talk about recipes and hygiene and things like that. They would also impart home economics information. There’s a lot of evidence of friendship quilts being made in the ’30s. There are a lot of album quilts that have names on them from the 1930s. There’s evidence of them from the 1840s, too. Maybe the women weren’t absolutely together all the time when they were making the quilts, but individuals would work on blocks and then put them all together and quilt them later.

I’ve been a member of a quilt guild since 1986. In our case, there are three different “bees.” There’s one that meets at night. There’s one that meets on Thursdays. It’s called the Thursday bee. And each one has a history. Each one has a little personality. You might feel comfortable at one but not at the other. I was always with the Thursday bee. And even though I don’t quilt so much, I’d go and sit, and they’d love hearing my stories or my adventures, my travels. So it serves a purpose today, too, a really good purpose.

Collectors Weekly: Is quilt making an American pastime or is it happening all over the world?

Waldvogel: Quilt making is popular all over the world right now. There are big contests, big shows. When I went to Japan, I found something really unusual. There is a traditional way of teaching craft in Japan, where you become a student of a particular teacher and you never leave them. And they transfer that to quilting, too.

The show I went to in Yokohama had probably 10 teachers represented, and each teacher had maybe 20 to 25 students. And there was an exhibit of each of the teachers’ students’ work. And the students’ work was so controlled by the teacher and the teacher’s methods that the work of all the students, for the most part, looked the same. It was a pretty brave person to break away from that system, and I did meet a group of women who had broken away and formed their own art quilt group.

Collectors Weekly: Can you tell us about some of the quilters who are well-known for either their technique or style?

Waldvogel: There are definitely quilt stars, and they rise above the others because maybe they’ve made a quilt that won a top prize, maybe they’re a very good speaker. They do attract a fan base. Companies will ask them to endorse products or to design a line of fabric and they’ll put their names on the fabric. I think people would consider Caryl Bryer Fallert a quilt star of today. She just won Best of Show again at the Houston Quilt Festival. I can look at a quilt today and say that’s a so-and-so quilt. In fact, there is an unwritten law or rule in the United States that if you have taken a class from a teacher and your quilt reflects that teacher’s work or if it’s a pattern that the teacher gave the class, you need to credit that teacher. It’s not your quilt yet.

There have been famous quilters throughout history. Mary Simon, for instance. We don’t know a lot about her, but she lived in Baltimore in the 1840s and ’50s. And her work shows up in Baltimore Album quilts. There’s a woman named Elizabeth Keckley who was a black woman, a freed slave, who lived in St. Louis. She bought her own freedom, and she ended up being the dressmaker for Mary Todd Lincoln in the White House. Susan McCord, that’s another name that we all know. She made quilts in Indiana in the late 1800s, and a group of her quilts were acquired by the Henry Ford Museum in Detroit.

Because some of these quilts ended up in museums in the early part of the 20th century, we know about these women. That’s how they got star status. Marie Webster, whom I mentioned earlier, was a quilt designer. She was a trendsetter. She made all of her designs. She made the quilts. And her quilts were the first ones that were published in color, in 1911 in Ladies’ Home Journal. People wanted to make quilts like Marie Webster made.

The purpose of those state quilt surveys in the 1980s was to try to find more of the anonymous quilters who had been overlooked by earlier quilt historians and museums in the early part of the 20th century. That effort was really incredible. Almost every state in the United States had a survey; there were books and exhibits. It was neat when you could find a group of quilts made by one person that were still intact.

Collectors Weekly: How did quilt making change after World War II?

Waldvogel: Quilting died out during the war because there was a shortage of fabric. And then my generation came along, the baby boomers. The last thing my mother wanted to do was something old fashioned. She was a modern woman. They had a brand new house in the suburbs. To them, scrap patchwork meant poor; it reminded them of a time they didn’t want to think about again. It wasn’t until the 1970s that the pendulum swung and we began to be interested in quilts and “women things.” A lot of quilts were made at the time of the bicentennial in 1976. And quilt guilds were formed soon after that. Today most quilt guilds are 30 years old, or more. Ours was formed in 1980.

People thought quilting was going to stop with our generation. But I think there’s a young group of people making quilts now. And to the credit of the industry, they’re listening to the young people, and there’s a lot of stuff online. They’re open-minded to whatever people want to make. We had a quilt entered in our contest. It was plastic with photo transfers onto that plastic. Interesting. And it is the quilt format. You’re not going to sleep under those, but it’s like the crazy quilt. It’s expressive. It’s creative. I think that’s what is neat about quilt making. There are a lot of ways to get involved. It’s open-minded enough. At a contest, you might run into a judge who would say, ‘That’s not a quilt, I’m not going to give that person the prize’. Well, so what?

Collectors Weekly: Thank you, Merikay, for taking the time to speak with us today about the history of antique and vintage quilts.

(All images in this article courtesy the Quilts of Tennessee Collection from The Quilt Index)

The Beautiful Chaos of Improvisational Quilts

The Beautiful Chaos of Improvisational Quilts

Collecting American Quilts: An Interview With Merikay Waldvogel, Part Two

Collecting American Quilts: An Interview With Merikay Waldvogel, Part Two The Beautiful Chaos of Improvisational Quilts

The Beautiful Chaos of Improvisational Quilts The Quilts of Winterthur

The Quilts of Winterthur QuiltsQuiltmaking and patchwork have been popular pastimes in the U.S. since the …

QuiltsQuiltmaking and patchwork have been popular pastimes in the U.S. since the … Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Wonderful, I spend my time copying old quilts like the ones shown above and you have just given me more ideas. I love making them the proper way, as they used to be, but dont forget patchwork may have originated in England and I aim to revive the English quilt. I like to use old fabrics and they have a lovely vintage feel when finished and my quilts have ended up from the North to the South of England and I live in South West Cumbria where many, many quilts were made – I just wish people had kept their Grandmothers quilts. So many people have told me they threw them out when their Mother or Grandmother passed away – how could they?

I am quilting an old quilt top which a friend found in her great-grandmother’s cedar chest. The fabric has been cut into diamonds & sewn into stars. My friend & I are 65 years old. I guess the fabric is circa- 1930??, but not known.

My friend thinks the fabric is feedsacks/floursacks. I have never seen feedsacks/floursacks stamped with 3/4 inch numbers & some letters such as ACA MD5 & 375513 The diamonds are scraps of fabric sewn with as many as 6 seams in one diamond. The diamond measures 7inch X 4-1/2inch, not one diamond has all the letters/numbers in the cut diamond to read. I was told this could be a shipping lot number to the store to be delivered. I was also told this could be railroad shipping numbers. Can you tell me why the black numbers are stamped on the fabric? If washed, I don’t think the black ink would be washed out.

Sincerely,

Emma Phariss

I was given a quilt by a close friend it was registered in 1976 it is the star of ’76 bicentennial quilt made by Mrs. erle Wilkinson ,president ,ama auxiliary . it was made from the Tennessee medical association auxiliary and recorded by B & B Needlecraft number 100 and officially recognized commemorative of the American revolution bicentennial administration . license no. 76-19-0551 authorized under public law. I have all the original documents and a picture of the person who made it holding the quilt . the quilt is in mint condition and I would like to know more about it and more on care instructions on an old quilt like this that seems to have some importance along with being made in 1976 .

Why was paper used on the back of the cloth when making a quilt?

When I was little in England I used to watch my friend’s grandmother doing amazingly beautiful crazy patchwork, using pieces of velvet, with feather stitch embroidery. That was in the 1940s, so she must have been born around 1880 at a guess. She sewed the pieces to a sheet of newspaper. I think she turned over the edges of the patchwork pieces as she attached them and blind stitched – or maybe did a running stitch as it would have been hidden by the embroidery. I am guessing that she tore the newspaper off when the block was finished? Presumably newspaper was used for economy. They often used old blankets or curtains to back the finished “quilt” – no batting and no actual quilting or tying of the layers.

I have always wondered about the paper on the back of string pieced quilts…. do you take it off…. quilt over it,,,, what about washing a quilt like this?

I saw a most amazing old quilt on Beatrix Potters bed, in her house Hill Top in Cumbria. It had been given to her by an American friend. But there wasnt much more information available about it that i could see on my visit. there is a nice photo of it here https://www.pinterest.co.uk/pin/185703184608294623/

i wished i had asked about it during my visit but there was so much to see!