If you were committed to a psychiatric institution, unsure if you’d ever return to the life you knew before, what would you take with you? That sobering question hovers like an apparition over each of the Willard Asylum suitcases. From the 1910s through the 1960s, many patients at the Willard Asylum for the Chronic Insane left suitcases behind when they passed away, with nobody to claim them. Upon the center’s closure in 1995, employees found hundreds of these time capsules stored in a locked attic. Working with the New York State Museum, former Willard staffers were able to preserve the hidden cache of luggage as part of the museum’s permanent collection.

“There were many patients in these asylums who were probably not unlike friends you and I have now.”

Photographer Jon Crispin has long been drawn to the ghostly remains of abandoned psychiatric institutions. After learning of the Willard suitcases, Crispin sought the museum’s permission to document each case and its contents. In 2011, Crispin completed a Kickstarter campaign to fund the first phase of the project, which he recently finished. (Crispin’s current Kickstarter campaign would help him to finish the project entirely.) Next spring, a selection of his photos will accompany the inaugural exhibit at the San Francisco Exploratorium’s new location.

Crispin’s photographs restore a bit of dignity to the individuals who spent their lives within Willard’s walls. Curiously, the identities of these patients are still concealed by the state of New York, denied even to living relatives. Each suitcase offers a glimpse into the life of a unique individual, living in an era when those with mental disorders and disabilities were not only stigmatized but also isolated from society. (All photos by Jon Crispin.)

Thelma’s suitcase.

Collectors Weekly: How did you come across this collection?

Jon Crispin: I’ve worked as a freelance photographer my whole life. In addition to doing work for clients, I’ve always kept my eye out for projects that interest me. In the ’80s, I came across some abandoned insane asylums in New York State, and thought, wow, I’d really like to get in these buildings and photograph them.

So I applied for a grant from the New York State Council on the Arts, got it, and spent a couple of years photographing the interiors and exteriors of these buildings. When the psychiatric programs moved out and shut things down, they basically just closed the doors and walked away. They left all kinds of amazing objects inside these buildings, including patient records in leather-bound volumes.

The exterior of Chapin House, Willard’s central building that was demolished in the 1980s.

In the mid-’90s, I heard that at Willard—one of the asylums in which I spent a lot of time photographing—the employees had saved all the patient suitcases that belonged to people who came to Willard and died there. Starting around 1910, they never threw them out.

“I don’t really care if they were psychotic; I care that this woman did beautiful needlework.”

Craig Williams at the New York State Museum fights an ongoing battle to bring objects like these into the collection, and that’s what happened. Willard was being closed as a psych center and converted to a treatment facility for criminals with drug problems. So the New York State Museum received this collection of suitcases, and displayed a few of the cases in 2004. I asked Craig if I could photograph these things, and he said, “Go right ahead.”

Forgotten band instruments at the Utica state facility.

Collectors Weekly: Why do you think the suitcases survived so well?

Crispin: Willard is this tiny town where multiple generations of people worked in the asylum, like a father would work there and then his daughter would be a nurse there, and so on. I have a theory that the relationship between the patients and the staff was so close, that the staff couldn’t just throw these possessions away when they died. There’s a cemetery on the grounds, and most of these patients were buried right there. And they kept storing their suitcases and moving them around as certain buildings were closed. Then, of course, with de-institutionalization huge numbers of patients were basically turned out onto the street.

Collectors Weekly: Why were the suitcases left untouched for so long?

Crispin: Willard was a facility for people with chronic mental illness. Originally, doctors thought that all you had to do was remove people from the stresses and strains of society, give them a couple of years to get their life together, and they’d get better. Eventually people realized they needed facilities where patients could come and never leave. There’s some question as to whether or not the patients themselves packed their suitcases, or if their families did it for them. But the suitcases sent along with them generally contained whatever the incoming patient wanted or thought they might need.

Clarissa’s suitcase.

Collectors Weekly: What makes you think the patients had access to their suitcases after they arrived?

Crispin: There were many levels of mental illness in these places. Some people were in really bad shape, and sometimes had to be restrained, completely unable to function in any kind of society or environment. Those people probably did not have access to their suitcases.

“It wasn’t some hellhole where people were chained to the walls.”

But a large number of people at the asylum were ambulatory. They were out and about; they worked at the farm; they did artwork. Some of these places even had their own dance bands. The Utica State Hospital had a literary journal. There were many patients in these asylums who were probably not unlike friends you and I have now. The reasons why people were put in these facilities ranged from everything to serious psychoses and delusions to people who couldn’t get over the death of a parent or a spouse. Other people were institutionalized just because they were gay.

Freda’s suitcase.

Initially, my idea was to pair the suitcase photographs with some indication of why these people were in Willard. As the project evolved, I found I wasn’t that interested in such a literal connection. The suitcases themselves tell me everything I want to know about these people. I don’t really care if they were psychotic; I care that this woman did beautiful needlework. I’m much more interested in the objects themselves and what people thought was important to have with them when they were sent away.

Some people at Willard definitely had access to the things they brought with them. For example, one case was filled with what look to be leather-working tools, and it’s pretty clear that this person used those tools because these facilities had time allotted for arts and crafts. The suitcases also contain lots of letters received by people while living at Willard, and there were lots of letters that were written at the asylum but never mailed. There were also examples of things written by people who were obsessive-compulsive, like the guy who wrote down the name of every railroad station in the United States on page after page of his notebooks.

Anna’s suitcase.

Collectors Weekly: Can each suitcase be traced to an individual patient?

Crispin: I have access to all the names, and New York State has the medical records for anyone admitted to these hospitals since the 1850s, so their histories are well-documented. I would like to use their full names in the photographs, but because of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), the laws about medical records and privacy, there’s some question as to whether or not I could be vulnerable to a lawsuit by the state.

Anna’s suitcase contained an inventory of her glamorous clothing.

Here’s a weird story: When I do the shooting, my digital photographs are labeled with what’s called IPTC information. It’s all the camera metadata stored with each photo, and you can add whatever you want. I typically add my copyright information, and also the names of the Willard patients for my own records. But when I upload photos to my blog, I strip that out.

For one person’s suitcase, I forgot to delete their name. Two days later, I got a call from someone who’s desperate, saying, “Do you have the objects of —?” and she gave the name of the person. And she said, “That is my grandmother. We didn’t know anything about her.” She had Googled her grandmother’s name and came across the Willard suitcases on my site. But even in this situation, the woman had to prove to the state that she was not only the granddaughter of this person, but that she was legally the recipient of her estate. So, in other words, if the grandmother had willed her estate to the other side of the family, this woman would not have been able to get access to her things.

One of Eleanor’s five storage containers.

I’m still trying to figure out how I can name these people, because I think it dehumanizes them even more not to. People who’ve been in mental institutions themselves have said, “Your project is very moving to me, but I’m very disappointed that you have to obscure names.” I think the stigma of mental illness has evolved from something shameful to something that’s much more medical and much more accepted. It just happens to people. But I’ve been very careful at this point in obscuring names, because there are many documents within the cases with names on them. I’m not showing their medical records; I’m only talking about the fact that they lived at Willard.

Collectors Weekly: Why weren’t these suitcases returned to family members when these people died?

Crispin: They tried, and again, the issue had to do with HIPAA laws. Contacting people with the information that their suitcases were in possession of the state was complicated by HIPAA. But the other problem was that a good number of these people were basically abandoned by their families, and their relatives showed very little interest in receiving their things after they died.

A detailed view of Eleanor’s sewing supplies.

Collectors Weekly: What was the process like to shoot the suitcases?

Crispin: Well, when I originally shot the asylums, I would walk into a building or into a room, and I wouldn’t move anything. I prefer being honest in documenting what was already there. But in this situation, you might have a suitcase filled with 30 individually wrapped items that I had to unwrap and position.

The museum had three interns go through every case to catalog the contents and preserve them, essentially taking things that were floating around loose inside the cases, wrapping them, documenting them, and then put them back in the cases. So when I open a case, I’m also recording the way the museum did this, unwrapping the items, photographing them, and then putting it all back.

Crispin also documents the way each item is wrapped and protected by the museum.

It’s a little hard for me because I don’t like to spend a lot of time laying things out, so I basically try to put the objects in a situation that looks as natural as possible. Especially hard were the suitcases filled with clothing. I’m not one of those studio guys who loves to set stuff up and get the lights perfect; I would’ve preferred opening up the case and photographing the inside exactly as I saw it, but that wasn’t possible.

Floyd’s empty suitcase.

There are still empty cases that I haven’t photographed, but even those are interesting to me just as suitcases, and there’s a whole group of people that love old suitcases. I think one of the reasons the project has been so successful is because it appeals to people in very different areas. It appeals to people who had family members in psych centers or who worked in psych centers or who are interested in old Greek-revival architecture. I was posting a lot on my blog, and I got messages from people interested in fabric or needlepoint and ephemera like toothpaste tubes and stuff from the ’20s and ’30s that doesn’t exist anymore.

Collectors Weekly: Was there any single suitcase that stuck with you?

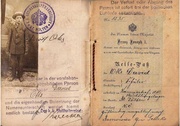

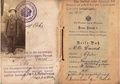

Crispin: One of the last cases I shot was from a guy named Frank who was in the military. His story was particularly sad. He was a black man, and I later found out he was gay. He was eating in a diner and felt that the waiter or waitress disrespected him, and he just went nuts. He completely melted down, smashed some plates, and got arrested. His objects were particularly touching because he had a lot of photo booth pictures of himself and his friends. Frank looks very dapper, and there are all these beautiful women from the ’30s and ’40s in his little photo booth pictures. That really affected me.

Frank’s suitcase included much military-related ephemera.

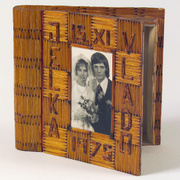

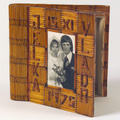

Dmytre’s suitcase is another that I really like, it’s the last case I did. Dmytre was very moving. He was Ukrainian and clearly brilliant. He had notebooks filled with drawings of sine waves and mathematical things like that. There’s a wedding picture of Dmytre and his wife, and she’s holding a bouquet of fake flowers, which were also in the case.

Dmytre was interesting because he got arrested by the Secret Service because he went to Washington, D.C. and said that he was actually married to President Truman’s daughter, Margaret Truman. And what’s great is there’s a little Washington monument thermometer in the case, so clearly he bought a little tchotchke on his trip to D.C. and then later got arrested for saying that he was Margaret Truman’s husband.

Some of the objects in Frank’s suitcase.

Obviously, some of the cases were a lot more mundane than others. There was one that had syringes in it that were so beautiful and old, and small drug packets with pills still in them. There were combs, books, bibles, clocks, and an incredible Westclox Big Ben alarm clock in its original box that’s unbelievably pristine.

There was lots of expensive stuff, like perfume bottles from Paris that were worth tons of money. People wonder, how is it that a woman who’s committed to Willard has a bottle of perfume, which even at the time was super expensive? Mental illness doesn’t target any one particular group of people; it takes all kinds.

Dmytre’s suitcase contained his wedding photo and the flowers carried by his wife.

Collectors Weekly: Did stories often emerge from the objects you found inside each case?

Crispin: You could tell a lot about a person by what was in their case. One of the most touching letters I read was written to a woman who had been in another asylum and then released and finally sent to Willard. There was a letter from her sister, saying, “You could come back to Erie, but I don’t want you living in the YMCA because they’re still really upset with you for trying to stab that girl.” That one letter tells you a ton about what this woman’s life was like.

Souvenirs and scientific notes found in Dmytre’s suitcase.

But every case was different; I was constantly blown away. It was very important to me not to carelessly rifle through these things and forget that they were somebody’s personal belongings. And I really have a lot of respect for these people as well as the nurses and doctors who worked at the facility. I came away from all of this and the asylum work I did in the ’80s thinking that the state was actually trying to help people. It wasn’t some hellhole where people were chained to the walls. They tried to help, and I think it’s important to keep that in mind.

While I was reverent, I tried not to be overly serious. I actually laughed a lot. If you’re ever around people in psych centers or even psychiatrists and nurses, a lot of their experiences are funny. Some of the items were amusing, but some made your heart ache, and others made you go, holy shit, what is this about? I was constantly affected by the items, and that’s my goal with photographs.

Flora’s trunk.

All photos by Jon Crispin.

If These Shirts Could Talk: The Tantalizing Tales Behind Used Clothes

If These Shirts Could Talk: The Tantalizing Tales Behind Used Clothes

The Politics of Prejudice: How Passports Rubber-Stamp Our Indifference to Refugees

The Politics of Prejudice: How Passports Rubber-Stamp Our Indifference to Refugees If These Shirts Could Talk: The Tantalizing Tales Behind Used Clothes

If These Shirts Could Talk: The Tantalizing Tales Behind Used Clothes Love Among the Ruins: Traveling Museum Excavates the Artifacts of Lost Relationships

Love Among the Ruins: Traveling Museum Excavates the Artifacts of Lost Relationships Art PhotographyIt shouldn’t be a surprise that photography became a vehicle for art and op…

Art PhotographyIt shouldn’t be a surprise that photography became a vehicle for art and op… SuitcasesIn 18th-century Europe, leisure travel was only for the rich. Their servant…

SuitcasesIn 18th-century Europe, leisure travel was only for the rich. Their servant… PhotographsFrom Mathew Brady's Civil War photos to Ansel Adams' landscapes to Irving P…

PhotographsFrom Mathew Brady's Civil War photos to Ansel Adams' landscapes to Irving P… Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

No places like that any more, so sad, now they put those poor souls on the street.

HIPAA has to do with medical records. It was not in place when these people were living so there is no violation of HIPAA. In addition, once a person is dead, there is no obligation to keep records secure. In reality, they have no rights. I would think that these do not belong to the state of New York but to the families of these patients, just like any unclaimed property.

respaect ,,thanks for sharing with us ,,god bless u

This is a very powerful site. The pictures are very touching. The stories in comments are even more powerful.

“Went crazy” was considered derogatory in the 1950’s, so I was never told that my mother “went crazy”, but that she had suffered a “nervous breakdown” She was institutionalized. She died before I turned 8.

I suffer long periods of clinical depression.

I found gozion’s story very pertinent, and dare I say, gozion, helpful.

More Joseph Cornell than an actual Cornell. Most touching.

You said you’ve chosen to omit full names, I found one in one of your photos..

Beautiful work. Have courage and conviction and do the full job. Name the people. Enable a just process and be the person who has the guts to enrich life. End the stupidity of this situation instead of exposing it and being an active participant in it.

This is the third time this was posted on my Stumble. a big stumble!

A moving article. Very poignant.

I have seen this display at our local arts center. It was such a powerful and moving thing to see. I too was moved by the story of Frank. The fact that many of these poor souls never were released is a crime.

It is a very interesting and touching article, like watching a movie and getting to know the intimate details of the people who were photographed. Mr. Crispin, you seem to be a very kind and compassionate human being!

When I worked with people who had serious mental illness, the saddest thing I saw were the black garbage bags in which they carried their possessions. No suitcases, minimal personal items. Many times the bags were left behind in their apartments when people were re-hospitalized. Their histories lost forever, thrown out with the trash.

I often wondered what it would be like to have no attachments to the past. No photos, no letters, no sense of, or links to any past life. This must contribute to the chronicity of the disease.

Thank you for offering the opportunity to get a glimpse into the lives of some people. I wish there was someway today to offer a safe haven, a sanctuary, for people and their possessions, a way to help them to stay tethered to their own histories, in this new world of “freedom”.

We visited the suitcase exhibit When it was in auburn, ny and it was definitely moving. My grandmother became a licensed “home” for elderly adults in the early 60’s, some of whom came from Willard. I never knew my grandmothers house without the “men” (as we called them) until she was too old to take care of others any longer. I could only imagine the life they would have had, had my grandmother not taken them in. For whatever reason they were with her, they all seemed perfectly normal to me as a young child. At her house, they recieved the proper care and treatment they probably wouldn’t had recieved elsewhere. They really all took care of each other, and there were a few who would hang out with my brother and I (just a couple of young kids ) and teach us to play cards or help us turn over rocks in the garden to look for bugs, maybe even push us on the swing. They certainly left me with fond childhood memories. God bless them all.

Fantastic to hear not all was cruel and nasty all those years ago, I’ve only ever heard of horror at these asylums, like Beachworth Victoria Australia. Thank you so much for sharing the suit cases!!

I’m a bit confused how HIPPA restricts you releasing the names of these people. Most of them died as late as the ’60’s. The asylum closed in 1995. HIPPA law wasn’t passed until 1996 and was to be fully complied with by 2003. These people weren’t even alive to have been given informed consent and acknowledgement of HIPPA. You can’t enforce a law that wasn’t a law at the time. HIPPA pertains to medical records. That is not what you are seeking. When a person dies they essentially have no rights. Their property becomes unclaimed property and can be claimed by family members with proof of relationship. Ask your state treasurer. I really think there is nothing they could do to you. Just my opinion. Fascinating work!

How strange that I randomly stumbled upon this site… I work in a Museum of Disability History in NY and an exhibit called “The Lives They Left Behind” just left our museum. It was based on the Willard suitcases.

Thanks for the excellent work. This is a story that needs to be known.

So much loss.

It is a real If Only sort of tug at the response that another human being makes to the world at large through perhaps just a handful of people and I fully agree how deeply digging would reveal how these people may have been cared for. It takes a really unselfish and efficient person for that “work” I recall a really natural young immigrant visitor to my Office workplace who worked as in such places. something I couldn’t do then or now.

Thank you for showing me a part of these peoples lives. It’s so necessary for them to be acknowledged, and honoured in this way.

as a young girl studying to be a nurse I was assigned to a large hospital in ca that I could see the patients got good care. the mental hospital today is much more organized those with the real bad problems need a haven to go to I had a friend who worked in a hospital in ca she told me that the patients had the best of care. god bless all of them for they are is the streets. getting beat up by god knows who being ignored by society I only wish I could do something for them but I cant.

Thank you for showing me a part of these peoples lives. It’s so necessary for them to be acknowledged, and honoured in this way.

Can these items and their stories still be viewed and where?

Fascinating,I would of never imagined such a thing.Great Museum Exhibit.

Thank you for showing me a part of these peoples lives. It’s so necessary for them to be acknowledged

I think its important to note that during that time period insane asylum patients weren’t all “insane”. There were more than likely a significant percentage of people that were simply autistic, developmentally disabled, or with down syndrome. There was no way to diagnose this so they were labeled as “insane”. The compulsive nature of some of those items reminds me of moderate to severe autistic behaviors.

“I think the stigma of mental illness has evolved from something shameful to something that’s much more medical and much more accepted.”

It’s interesting to look back on these things. While I don’t have a suitcase, I do have a small carpet handbag that belonged to my great grandmother (I’m 34 at the time of writing this) who died in a mental institution. I’m told by my mother that she used to burn herself with cigarettes because, quote “I can feel myself slipping away.” and given that dementia runs very heavily in my family, it sounds to me like she was trying to avoid losing her memories (herself).

Sadly, however, in the bag are all the letters she received while in the institution… letters saying “Get well soon.” and “Smile.” and “Keep your head up.” … we have indeed come a long way in understanding that mental illness is so much more than just a “bad day”. It’s a disability like any other.

That being said, the “get well soon” mindset still exists in people who have never had any sort of mental-emotional difficulties. but the example I always use is: You wouldn’t tell a physically ill person to “Just get up and walk!” so why would you tell a mentally ill person to, “Just cheer up!” ?

My grandmother went to an asylum and my dad and four siblings went to an orphanage in Peoria, Il. We have found out through ancestry investigation that she remained until sent to a catholic charities home in Chicago. Very sad I never had her in my life?

i worked 36 years at GREYSTONE STATE HOSPITAL IN MORRIS PLAINS N.J.

it was a real hell hole, in 1971 there where 7,800 lost souls there. the doctors did all kinds of experiments on these poor people, just like the GERMANS, its been many years since i work there but i still have NIGHTMARES

After finding this on utube quite by accident and reading all the posting of all sorts. The congratulations. .the stories from those who experienced terrible ordeals in our history’s mental institutions….and from myself having bouts of depression even in todays societies there is still a stigma of that person being off or not quite right…or comments of …i hope they are on medication or that they have taken it correctly. ..i was struck by the actual knowledge that these long ago asylums even attempted to keep patients personal items let alone cataloging them wrapping them and returning them in some order within the suitcases…and from being someone who loves vintage items it was such a treat to see the things really so lovingly cared for by staff…when obviously they must have known if they were buried in the hospitals version of potter’s field that no one would ever come claim these in most cases beautiful possessions that would then be stacked and forgotten in an asylum attic…we thank u sir for the glimpses you gave..

And that it allowed us for whatever reasons we each and everyone had for peeking in….

My aunt Edith Lowe was a patient.She died in 1943.My mother’s sister.She was never visited b by her family.I would be very thankful if I could get any information

absolutely amazing, these were real people who lived, breathed and felt emotions just like you and I. thank you for preserving the dignity of those people.

Wonderfull. Will go look for your kickstarter. I think Regan and Goo closing all mental healthcare is a travesty.

My ancestor lived at this hospital. I’ve been trying to get his medical records to find out if he died there or not. But the law states that you can only get the records if your doctor writes a letter stating that they are necessary for current medical guidance. Yyyyeah. I don’t think any doctor is going to write that. My ancestor is long-since dead; I really don’t understand the problem of us finally learning about him!

Amber Elizabeth Ridgdill- Girl, you said it! I have a serious, degenerative genetic disorder that puts me in agony 24/7. I can’t count how many hundreds of people have told me over the years to “feel better soon!” I know that they’re just being polite, but it really starts to get annoying when it’s said over and over and I’ve explained that each day is a little bit worse than the last. That’s the definition of degenerative. [rolls eyes]. Anyway, I feel for your grandma! Your comment was so interesting to read. It reminds me of a conversation I had once. I found someone a few years back who was 99 years old. When she was a child, she knew my 3-times-great-grandfather! How cool is that?! She told me he was crazy, and that he didn’t even remember his children. She said one day his son told him to take a bath, and he packed up a knapsack and ran away! She went on and on about how crazy he was. A couple days after that conversation, I realized that he probably had Alzheimer’s like his descendants- my grandma and great-grandma! “Crazy” is in the eye of the (often un-educated) beholder.

I love your comments about the people and the items that were still there. I think that that was Beautiful, Mainly about bringing this to light. Especially over the fact that the nurses had enough respect for the people as people Not The Mentally Disturbed (or a crazy person) as most would say , that they saved the items still in the Attic for the story of these people would come out. Thank You for your comments and the story of the people themselves . Thank You Again

Jon, your compassion towards all those lost people & their possessions is so selfless. It’s very sad that so many of the people that were sent to Willard never saw the contents of their cases that accompanied them. I wonder who made that decision. I’m sure it just added to their distress – rather cruel.

Do you have any plans to put this work into a book?

Very interesting, Thanks for posting it.

Thank you for a very interesting read. I am sure many people and relatives would welcome knowledge of their loved ones. I hope there will one day be a means of releasing this information to their descendants. Thank you for dealing so sensitively with this subject and giving every patient dignity. A truly worthwhile project!

It’s frustrating to me that in the many articles like this one about Mr Crispin’s continuing work on this project he never credits the significant groundbreaking research and advocacy of Darby Penney and Peter Stastny who, collaborating with the NY state museum, uncovered these stories and first gave voice to the owners of these suitcases.

http://www.suitcaseexhibit.org/index.php?section=thebook&subsection=thebook

IS’T LIFE SAD & FRAGILE ?

I have 5 ledgers from eloise mental institution in mich , some are over 100 years old,, trying to find a place to give them to,, Eloise museum has not responded,, , you have any ideas??

These are not just suitcases, each suitcase is a story in itself

I think it’s important to humanize patients with mental illness. I have five woman ancestors who were patients at state hospitals. I have researched and written about them because I feel that their trauma has been passed down to subsequent generations due to the shame and secrecy that shrouded their stories. As their direct descendant, I was able to obtain their patient records from Norwich State Hospital. I maintain a blog in which I share what I have learned about my family and about the history of mental health care in the first half of the 20th century. https://juliannemangin.com/2017/11/08/norwich-state-hospital/

George Coon, my grandmother is also Edith Lowe (daughter of John and Pearl)

My mother was put up in foster care in 1932. We never knew of Edith until this year. Soo many questions! Please contact me. Msfalcon@hotmail.com

In regards to post#30

If you still have those Eloise ledgers I’d love to copy and put them on my Eloise blog: portraitsofeloise.blogspot.com

Can you add the bio of each person the case belonged to on your website? That would really compliment the case folder pictures, really would love to know the back story on these people. Thanks! Sorry, but privacy laws pertaining to patients prevent that. -Eds

My great-grandmother, Maria Carbone Milazzo, died in Marcy State Hospital on November 7, 1941 at the age of 70. I would like to have any records or items from her time in this facility.

my dad they thought had bad depression, they brought him to Loudes knickerbocker private asylum in Amityville, NY. There they treated him with shock therapy but it wound up he had a brain tumor which burst from schock treatment. He passed at 30. I was only one and my brother 6 when he passed. He and my mom worked at Brookhaven Lab. We are trying to find any old records. I don’t believe he had this tumor before Brookhaven but in order to file for settlement we would need some kind of medical record. The type of tumor he had was quite aggressive and fast growing I have turned to my county, my m. edical examiner, NYS health in Albany I was hoping somewhere on microfische or somewhere I may find some records. Any ideas???

As a family historian and genealogist I feel that the surnames of these people should be told. We crave to know more about our ancestors and extended family. Many would dearly love to see photos of the belongings of their family. My grandmother was committed for a year in an insane asylum for post-partum depression, then called the “baby blues.” I’m so thankful that her husband’s niece got her out, otherwise I wouldn’t be here. I tried to get the records of her stay there; however, I was told that they did not keep the records. Thank you for sharing these moving photos.

No places like this anymore? Are you kidding? Check out mind freedom. I am a psych survivor. I spent two years locked up. I know many people currently committed, being given forced ECT, and being put in restraints or isolation. Don’t kid yourself. But most of the people locked up against their will either have money, insurance, or someone who benefits from the being locked up

.