If you resent St. Valentine’s Day because of its treacly obsession with romance, don’t blame Hallmark. The 20th-century greeting card company didn’t produce Valentine’s cards until 1913, and lovers and wannabe lovers had been sending each other sweet nothings on February 14 for centuries before that. In fact, Hallmark cashed in as the holiday became less romantic in the early 20th century, when family members and schoolchildren started to exchange Valentines, too.

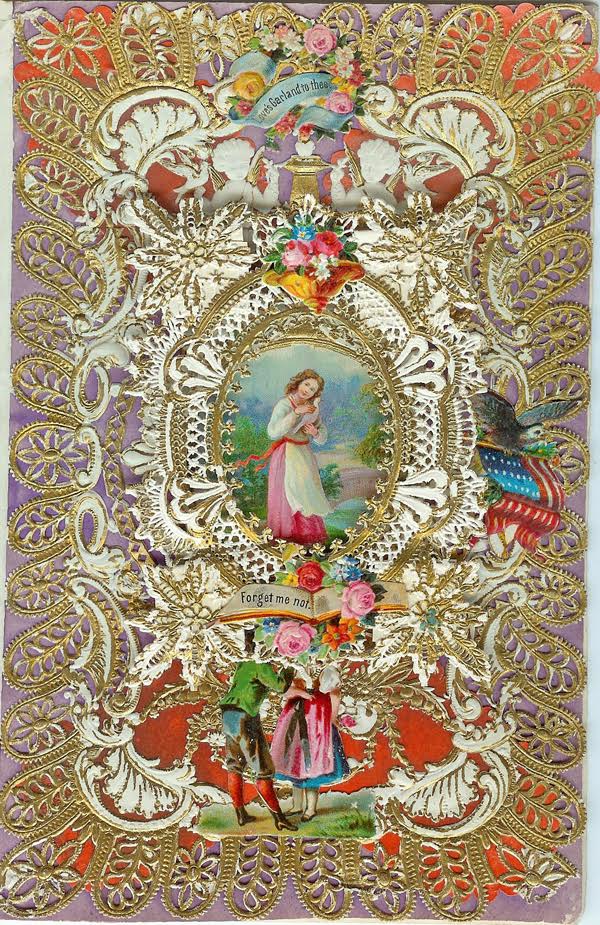

Perhaps the romantic side of the holiday has been unfairly maligned. If you look at Valentines from the early to mid-1800s, when the artistry of paper tokens of love reached its height, your hard heart has to soften just a little bit. Sure, these cards can seem overly frilly to modern eyes, but when you think about how much work went into every intricate detail of a Valentine—at a time when paper was treasured and not the disposable wrapping on your sandwich—you realize it wasn’t a frivolous endeavor.

Top: An antique Valentine “confection” made of glazed paper. (From the John Johnson Collection at the Bodleian Library, University of Oxford) Above: A Pennsylvania Dutch papercut “Fraktur” Valentine by Jacob Botz, circa 1780. (Courtesy of Nancy Rosin)

Nancy Rosin, president of the National Valentine Collectors Association, has Valentines so beautiful, sincere, and meticulously handcrafted, they’re sure to make even the most cynical among us swoon. “Life was very different in those times,” explains Rosin, who paints a picture of a besotted suitor, after a long day of labor, staying up at night working by candlelight, to write, draw, cut, weave, or fold the perfect Valentine using the luxury product known as paper. “Emotionally, Valentines were important because life was relatively short. Men and women wanted to get married, and they married young. Back then, you celebrated every moment of life—birth, death, love, marriage.”

The true origins of Valentine’s Day are about as hard to pin down as a cutesy, fluttering Cupid covered in baby oil. It’s the sort of holiday given to dramatic myths, many of which scholars haven’t been able to prove or disprove.

We do know that ancient Romans celebrated a wild fertility-boosting bacchanal called Lupercalia around February 13-15, which has also been linked to the Catholic celebration of Carnival, or Mardi Gras. Priests would sacrifice a goat and a dog, and then make whips from the animals’ skins. While people ran around drunk and naked, priests wearing the sacrificial hides would whip young women, who’d eagerly line up to get smacked, believing it would improve their chances of pregnancy.

One legend claims this ancient Feast of Lupercal also included a lover lottery in which each young man would pick a name voluntarily placed in an urn. That young woman would be his lover for the duration of the festival and, hopefully, the year. Some scholars dispute this, saying the first such matchmaking lotteries happened in medieval Europe. Others assert this festival was so popular that when the Catholic theocracy took over Europe, the Church couldn’t convince people to give it up, so they changed it to a feast in honor of a Christian saint named Valentinus.

Papercut “cobweb” Valentines contain a secret image or message under the surface. Below, see the image that’s revealed when you pull on the butterfly. (From the John Johnson Collection at the Bodleian Library, University of Oxford)

According to Catholic records, as many as three men named Valentinus may have been martyred in the name of Christianity during the Roman Empire. A bishop—who might account for both Valentinus of Rome and Valentinus of Terni—was beheaded by Roman Emperor Claudius II in A.D. 269 or 270. He was canonized by Pope Gelasius in A.D. 496, who outlawed Lupercalia the same year. After Valentine’s feast day was established as February 14, a writer described the story of the saint curing the blindness of Julia, the daughter of a judge who’d thrown him in jail—a story repeated in the in The Nuremberg Chronicle, written in 1493. This miracle convinced her whole 49-member family, including the judge, to convert to Christianity. Later, the tale was embellished to include the martyr sending a note to Julia signed, “Your Valentine.” Contradicting the ancient records, another legend asserts that Roman Emperor Claudius II also banned his soldiers from getting married, but that Saint Valentine was caught performing secret weddings for the men. Supposedly, Valentine would hand out hearts made of parchment to remind soldiers of God’s love and their marriage vows.

A hand-cut paper Devotional parchment with a gouache image of Saint Paul, circa 1700. (Courtesy of Nancy Rosin)

It’s said the Pope kept the Lupercal lottery, but changed the focus to piety: Young men and women could draw the name of a saint to emulate all year. But young Roman men weren’t satisfied with the drawing and started writing notes to women they were interested in instead. During the medieval era, the matchmaking lottery known as “drawing lots” involved two boxes, one containing the names of single men and the other single women. A name would be drawn from each box, and the two declared a couple. The pair would exchange presents, and then the man, duty-bound to protect his new sweetheart, would wear her name on his sleeve for a year. In France, the woman was required to make a meal for and attend a dance with her drawn Valentine, but if he rejected her, she had to stay in seclusion for eight days.

“The romantic idea of Saint Valentine, as someone who was beloved himself as well as a friend of young people for encouraging love, has remained,” Rosin says. However, the Catholic Church was determined to keep the focus on God’s love. “By about the 1400s, nuns in French and German regions were creating vellum-parchment tokens called Devotionals, which would be sold for charity. Laypeople would give them to one another for any event—for marriage, communion, mourning, or love—and keep them in their Bibles. In the center of the Devotional would be a cartouche with a painting of a saint or a Sacred Heart, and for its border, the nuns would execute delicate knife-cut designs similar to tatted lace in the paper. We see similar designs later in Valentines with lace borders, and the religious hearts of the saints evolved into the secular hearts of lovers.”

Rosin explains that a religious card might depict the Sacred Heart of Jesus or an “endless knot.” These images of Jesus’ unconditional agape love and the path to spiritual enlightenment eventually evolved into symbols of romantic love.

This hand-colored lithographed Valentine is adorned with sequins and features the “endless knot of love.” Postmarked February 14, 1814, it’s a form of mail known as a “stampless cover,” meaning the note was folded and sealed with wax and it would have been hand-carried or delivered by horse courier to a woman named Susan in Cambridge, England. (Courtesy of Nancy Rosin)

“The ‘endless knot of love’ is a common motif, which, like the wedding band, has neither beginning nor end,” Rosin says. “It comes from the German irrgarten, or a religious maze. The idea was that at the end, you would find enlightenment or Jesus Christ. Later, you have Valentines that have a labyrinth, but instead of finding Christ, it’s all about finding true love.”

The tradition of sending Valentine’s Day cards may have evolved not only from lofty ideas about God’s love, but also the notion of platonic love between friends. German-speaking countries such as Austria had a tradition in which one would drop by a friend’s home on New Year’s Day, and if you didn’t catch them, you’d leave a note wishing them season’s greetings. These notes evolved into Freundschaftskarten, or “Friendship Cards,” which were also given on birthdays, anniversaries, and your Name Day, or the annual celebration of the saint you were named after, which was then more important than your birthday. Handwritten or printed Friendships Cards usually featured a verse, which could also be romantic in nature.

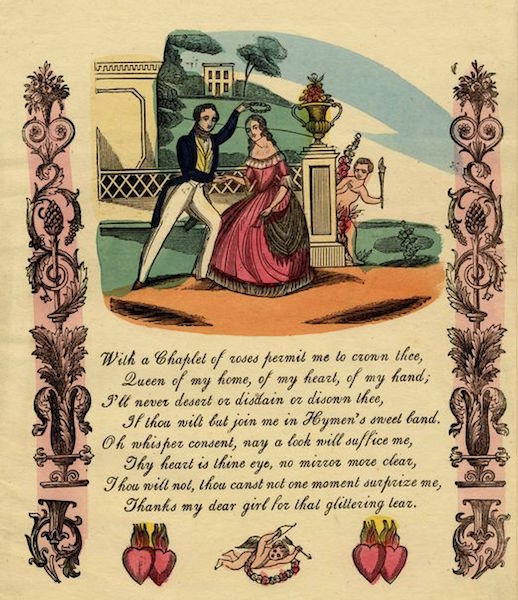

This Valentine, a hand-colored wood engraving, features a romantic poem and symbols of love, including the “Sacred Hearts.” (From the John Johnson Collection at the Bodleian Library, University of Oxford)

Chaucer’s 1382 “Parliament of Fowls” is the first writing that associates Valentine’s Day with romance, with the verse, “For this was on St. Valentine’s Day, when every bird cometh there to choose his mate.” Considering the mating patterns of birds in England, scholars have theorized that Chaucer was actually referencing the feast of St. Valentine of Genoa, a bishop who died around A.D. 307 and was usually honored on May 3. But because of the changes to the Gregorian calendar, Chaucer’s February 14 would have been our February 23, a time when English birds are just beginning to mate.

“Valentines were as inventive as the love, I guess. If the person was devoting a lot of time to it, he might be very creative.”

Around 1400, Charles VI of France wrote about an elaborate feast with romantic songs, poetry, dancing, jousting, and even a “Court of Love,” where women would rule on the disputes of lovers—but no one knows if such an event ever occurred. The first known Valentine was sent in 1415, from 21-year-old Charles, the French Duke of Orléans, who was being held prisoner in the Tower of London after he had been captured in the Battle of Agincourt during the Hundred Year’s War. His poem starts with lines of yearning to his 16-year-old wife, Bonne of Armagna, written in French, “I am already sick of love, my very gentle Valentine.”

King Henry VII decreed, via a 1537 Royal Charter, that “Saint Valentine’s Day” would be honored in England on February 14. By the end of the 16th century, Valentine’s Day was a source of angst for poets such as William Shakespeare, John Donne, and Edmund Spenser. In the 1660s, British politician and diarist Samuel Pepys wrote about the men his wife drew in the Valentine’s lottery and of buying his mistresses expensive Valentine’s presents such as embroidered gloves and rings, as well as shoestrings, silk stockings, and garters. He also wrote of popular holiday superstitions, like the idea that a woman would marry the first man she sees on Valentine’s morning.

When closed (at top), this brown paper Valentine, made in Germany circa 1860, looks like a real pair of leather gloves. (Courtesy of Nancy Rosin)

“In Pepys’ diary, he writes about a paper Valentine with letters written in gold,” Rosin says. “But before that, the Valentine was considered the person you loved, and not your gift for him or her. Pepys talks about these expensive gifts, like jewelry or lingerie. Lace handkerchiefs, which would be carried at a wedding, were also popular. A woman might receive a silver locket or a container for perfume, and men could receive snuff bottles. A sewing case known as an etui with beautiful French enamel would be a luxurious gift. Chocolate was a major gift, too, because people considered chocolate an aphrodisiac.”

Thanks to a growing interest in botany, the coded means of communication known as the “Language of Flowers,” or floriography, came to Europe from the Ottoman Empire in the early 1700s. A lover could express an elaborate message through a bouquet or a hand-colored etching of a bouquet. A red camellia said “You’re a flame in my heart,” while a striped carnation meant, “No, I can’t be with you” and a purple hyacinth said, “I am sorry, please forgive me.” A daisy stood for “pure love” while a scarlet zinnia represented “constancy” and a dandelion “happiness.” Red roses, thought to be the preferred flower of Venus, Goddess of Love, became an enduring symbol of romantic love. Thus, flowers, especially red roses, and also pictures of flowers became an important part of Valentine’s Day.

A detail of an American Valentine from 1825, which was stencil-painted with a rose wreath symbolizing endless love. This craft, known as theorem painting, was taught to women and girls in schools in the early 19th century. (Courtesy of Nancy Rosin)

By the early 19th century, people from all levels of British society were exchanging handwritten notes and other tokens of affection. Derived from Devotionals and German Friendship Cards—which had grown more and more beautiful over the centuries—paper cards or letters became treasured Valentine’s gifts, exchanged by both platonic friends and lovers. (Even children participated in Valentine’s Day in the 1800s, by singing holiday carols at school.) At the time, new paper mills were producing fine paper from the rags of linen, cotton, and hemp, and it was expensive enough to be considered a luxury or indulgence. Simple pulp cards embossed with sweet images and messages were also sent as Valentines.

“Early Valentine cards featured simple designs, like one I have from around 1750 with an embossed bouquet of flowers and one little line about love,” Rosin says. “As soon as stationery paper became available, people would just write a poem in the middle of the decorative border, and that might be the Valentine. Toward the end of the 18th century, Valentines grew more elaborate.”

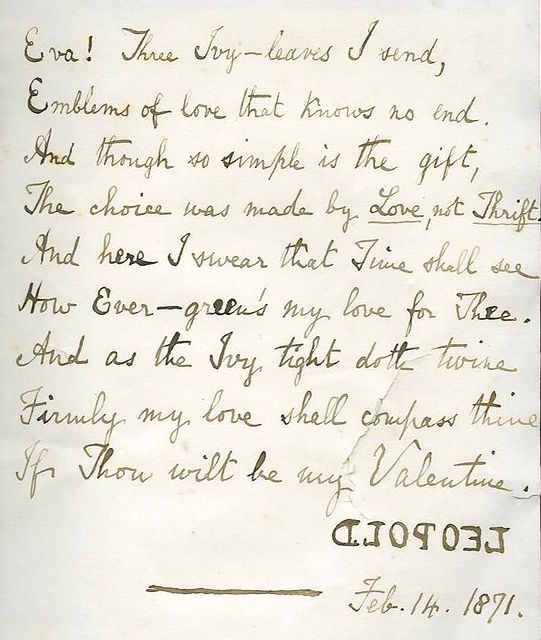

Leopold placed this poem to Eva and wooden jewelry inside a Valentine by Eugene Rimmel. Notice he signed his name backward. (From the collection of Michael Russo, vice president of the National Valentine Collectors Association)

Because polite society in the 18th and 19th centuries demanded that people keep their passions to themselves, Valentine’s Day flourished. It gave both men and women a fleeting opportunity to express their true feelings without risking total humiliation. “Valentines became a way that a woman could express affection because they were generally sent anonymously,” Rosin says. “Sometimes collectors find a blank antique valentine and say, ‘It was never used.’ But it might have been used, because it was not unusual for them to be delivered unsigned. If they were marked, sometimes it was just the initials, or the name written backward, or it just said ‘From a serious admirer.’”

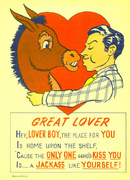

Part of the game was figuring out who it was from, Rosin says. Often admirers would deliver the message themselves by hand, slipping their Valentine under the door or hanging it on the doorknob. But finding a Valentine wasn’t always a delight: People also used the holiday as an opportunity to anonymously air their grievances toward one another with so-called Vinegar Valentines.

Before the modern postal service, receiving mail in England was complex and expensive—which is why so many Valentines were hand-delivered. The cost was calculated by distance and per sheet of paper, and the fee was paid by the recipient, who would likely turn down a letter they couldn’t afford. For this reason, instead of being wrapped in another piece of paper (an extra charge), most early paper Valentines were “stampless covers,” a form of mail in which the note is simply folded and sealed with wax for privacy.

The frontispiece of The New Trades Valentine Writer, circa 1845. (From the John Johnson Collection at the Bodleian Library, University of Oxford)

“You didn’t use a homemade envelope, because it would have cost more, and the person who received it had to pay to accept it,” Rosin says. “If a man’s daughter received lots and lots of these Valentines from admirers, he might have declined them and said, ‘I’m not paying for any more.’ So those Valentines wouldn’t get delivered.

“A Valentine was sometimes just a romantic letter on a beautiful piece of stationery folded and sealed with wax,” Rosin says. “Even the imprints in the wax might convey a secret romantic message. I have love-letter seals, including sets of six, with a different design for every day of week except Sunday, because you didn’t send a love note on the holy day.”

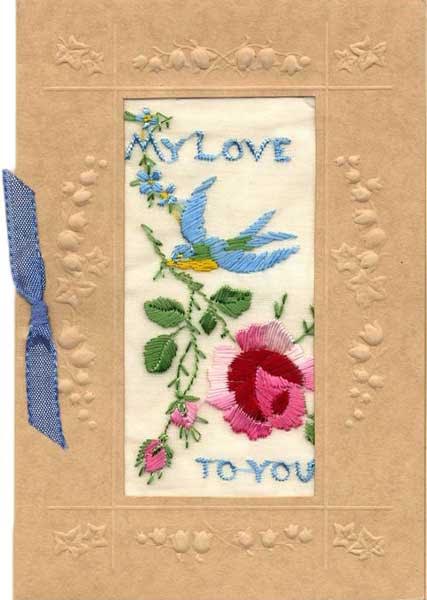

An embroidered silk Valentine with a paper frame embossed by Raphael Tuck & Sons. (From the John Johnson Collection at the Bodleian Library, University of Oxford)

If a young woman’s father was the sort to refuse to pay for the post, she might have him to blame for her spinster status: Some Valentines, Rosin explains, were sent as wedding proposals. A Valentine might include paper gloves or a paper wedding band—or a metal ring or real fabric gloves—and she knew what that meant. “If a woman received gloves for Valentine’s Day and she accepted them and wore them Easter Sunday, it was an acceptance of a marriage proposal,” Rosin says.

Before Valentines were mass-produced, people had to get creative. Women might embroider messages of love on fabrics. Some suitors wrote verse in beautiful calligraphy on a piece of embossed paper stationery, but if they lacked the skills to do so, they could pay for help. Better stationery shops offered a service where a clerk with lovely handwriting would write out your Valentine poem for you. And if you had trouble coming up with an appropriately romantic rhyme, you could purchase a broadside or chapbook known as a Valentine Writer, which provided both initial declarations of love and also poetic responses for the recipient.

“Some of the poems were meant for stylish, elite people,” Rosin says, “and others were for tradesmen. The baker’s poem might say, ‘I knead your dough.’ Maybe the woman would have the same little booklet, and she could respond. But I’ve never been able to put any of the poetry that I see in these booklets to an actual valentine. Although some of the writers in my collection have little notations in pencil and little scribbles.”

Rosin says while the Valentine Writers offered women poems to send as polite rejections, she’s only come across one 19th century Valentine declining a suitor. “One of the first pieces I ever bought has a line written on the bottom saying, ‘No, sir, I do not require your love.’”

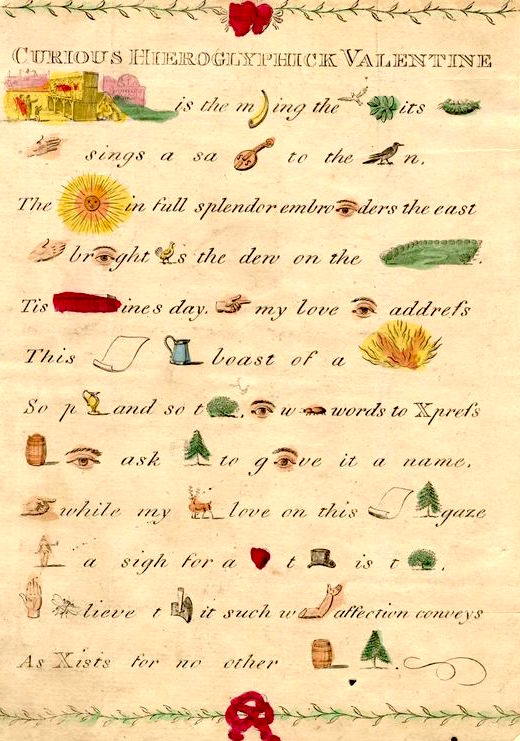

This engraved Valentine rebus puzzle was hand-colored. (From the John Johnson Collection at the Bodleian Library, University of Oxford)

Some admirers created puzzles like acrostics, or verses that used the first letters of their sweethearts’ names, or rebuses, which replace certain words or letters in the message with drawings representing them. Another popular Valentine riddle was a puzzle purse, a piece of paper carefully folded as many as nine times. The poem would run along the edge of the folds, and the recipient would have to open it in the right sequence to understand the message.

“The puzzle purse was folded very tightly,” Rosin says. “As you would open it up, there would be messages all along. It might be hard to refold it, as a matter of fact. It might even have numbers indicating the order in which you were supposed to read the panels to decipher the message. The puzzles that were used in Valentines were as inventive as the love, I guess. If the person was devoting a lot of time to it, he might be very creative.”

This puzzle purse from 1797, sent to Gordonstown, Scotland, was hand-painted with symbols of affection. (Courtesy of Nancy Rosin)

In 18th-century America, an abundance of paper mills in Pennsylvania allowed the Germans who settled there, known as the Pennsylvania Dutch, to create beautiful illuminated documents, form of folk art known as Frakturs. The Fraktur style, which originated in the church and was taught to schoolchildren, was also applied to Valentines and love letters known as liebesbriefe. The Pennsylvania Dutch also brought a traditional Germanic paper-cutting technique known as Scherenschnitte to the colonies and employed it for silhouettes, Valentines, and love letters.

“If a man’s daughter received lots and lots of Valentines from admirers, he might have declined them.”

The art of the cutout was also important to British poet, charity founder, and abolitionist Elizabeth Cobbold, who, according to Rosin’s research, revived the concept of the Valentine lottery at her annual parties in Ipswich, England. Starting around 1806 until her death in 1824, every year, she and her 22 children and stepchildren would make gorgeous white papercuts and paste them to red backings for their celebration. Each Valentine, which also included a cryptic verse, would be placed in a basket and drawn by a guest.

“Just last May I visited the Ipswich house with Elizabeth Cobbold’s great-great-great-great-grandson, who showed me around,” Rosin says. “She would spend hours and hours on her cutouts, which reflected mythology, poetry, botany, and history, and she would write a poem for each. These would be folded, wrapped in paper, and put into a basket. A guest would pick one, and it would dictate who would be their Valentine.”

This Elizabeth Cobbold “lottery” Valentine from the early 19th century features a hand-cut design of medieval knights jousting, as well as a handwritten verse. (Courtesy of Nancy Rosin)

Around the same time, Austria, Germany, and Denmark entered a peaceful stretch of relative prosperity known as the “Biedermeier Period” (1815-1848), during which the new middle-class embraced a sentimental, apolitical aesthetic that focused on clean lines and pastoral scenes. The Biedermeier Valentines and Friendship Cards were delightfully inventive, particularly their “moveable” or “mechanical cards.” Sweet cartoons of country life would move or change when you pulled a tab. Lifting a flap might reveal a secret message of love. Other Biedermeiers had a device known as a “cobweb,” a circle-shaped paper cover that could be pulled out into a beehive-like lattice cone revealing an image or message underneath. These cards might be hand-painted, embossed, gilded, or adorned with mother-of-pearl.

“If a woman received gloves for Valentine’s Day and she wore them Easter Sunday, it was an acceptance of a marriage proposal.”

Some 19th-century women gave the men they loved a “watch paper,” a delicate little bit of paper slipped into his pocket watch to protect the movement from dust. “Every time the man opened his watch to see the time, he would see this message from his beloved.” These were similar to love tokens, or coins that were engraved with a message of love on at least one side, which could be kept in a pocket or worn on a piece of jewelry like a charm.

If a woman’s sweetheart were a sailor—who might be protecting Britain’s sea empire aboard a military or merchant ship, or hunting whales for their precious lamp oil—she faced the grim reality he may never return. So sailor tokens of love were particularly wrought, from beautiful glass rolling pins filled with the precious commodity known as salt to corset busks made from whale bone and scrimshawed with romantic imagery. For Valentine’s Day, seamen between 1830 and 1890 often brought home octagonal wooden boxes with a glass panel on the front, revealing an intricate seashell design, often of a compass rose or a heart. It is believed that these Valentine boxes were crafted by Barbadian women and purchased at a store called New Curiosity Shop in Bridgetown, Barbados.

Octagonal boxed seashell mosaics were made by women in Barbados and sold to British sailors as Valentines for their sweethearts in the 1800s. This example is particularly rare because it’s so large (15 inches wide) and the central circle of shell flowers is a removable wreath that a bride could wear on her wedding day. (Courtesy of Nancy Rosin)

But paper cards of the era could be just as ornate. During the early 19th century, paper mills produced reams of so-called lace paper, made of fiber rag pulp, with embossed cameos depicting couples, churches, cherubs, and figures from ancient Greek mythology. Lovers would buy this paper and layer and collage it with satin ribbons, silk chiffon panels, molded wax flowers, metallic Dresden ornaments, pieces of wallpaper, locks of hair, and other decorative scraps. Sometimes the messages of love would be buried beneath all the frills.

“Until the 1860s, you saw all these really beautiful confections of lace paper that were made by manufacturers,” Rosin says. “Or you could go to a shop that sold supplies and make them yourself. Experts say 1840 to 1860 was the Golden Era of Valentines, because they were just so elaborate. They got so heavy that according to Frank Staff in his book, The Valentine and Its Origins, they had to be boxed before mailing.”

This Valentine confection includes gauze and paper springs. (From the John Johnson Collection at the Bodleian Library, University of Oxford)

The tradition of sending Valentines exploded in the middle of the 19th century, but not just because the romance between Queen Victoria and Prince Albert and their 1840 marriage turned the Brits into a bunch of sentimental saps. We can actually thank two Industrial Age advancements: First, new machines produced cheap paper from wood pulp, which started to become available to the masses in the 1830s, allowing the average person to keep a journal or send letters.

Second, the British postal system underwent a huge reformation in 1840, so that for the first time anyone could send a letter of “moderate weight” for one penny. A prepaid rubber-stamped diamond-shaped letter wrapper known as the Mulready envelope was developed in the late 1830s, and it was followed by the introduction of the first adhesive postage stamp, known as the Penny Black, in 1840. In 1845, Edwin Hill and Warren De La Rue patented the first envelope machine, which cut paper into a diamond shape, then folded it into a rectangular wrapper. Their machine made a splash at the first world’s fair, the Great Exhibition of 1851 in London. These new envelopes eventually became as elaborate as the stationery paper they contained.

A “diamond” envelope (top) could be just as ornate as the Valentine it contained (bottom). (From the John Johnson Collection at the Bodleian Library, University of Oxford)

“The new postal system made mailing Valentines accessible to everyone,” Rosin says. “Then, in 1851, there was de la Rue’s machine, which was a magical advancement.”

Rosin’s research shows that by the 1830s, each year, roughly 60,000 Valentines passed through the London post office, when the city’s population was well over 1 million. Postal reformer Rowland Hill figured that 400,000 were sent in England in 1840, and more than 500,000 in 1850. In 1871, when the city’s population was over 3 million, more than 1.5 million Valentines were sent within London alone.

The United States also saw a major reduction of postal rates in 1845, and by 1851, a letter could be sent 3,000 miles for three cents. That same year, the United States government established postal routes in all cities and towns, eliminating the need for private delivery services, which brought people mail from the local post office. Thanks to these changes, sales of Valentines grew in America, too.

Esther Howland popularized Valentine’s Day in the United States selling layered confections of lace paper, scrap images, and Dresden ornaments, starting in the late 1840s. This early example is marked “H-100,” meaning it sold for $1. (Courtesy of Nancy Rosin)

While New York City lithographers and woodblock printers had been offering Valentines since the turn of the 19th century, one woman is credited with popularizing paper lace Valentines in the United States. Nineteen-year-old Esther Howland, whose family owned the largest book and stationery store in Worcester, Massachusetts, received an intricate English Valentine from one of her father’s business associates in 1847. Enamored with the idea, she convinced her father to order lace paper and embellishments like Dresden ornaments and George Baxter print images from London and New York City. When her brother took her samples on his sales trip, he returned with more than $5,000 worth of orders. Since Howland couldn’t make them all herself, she brought in her friends to build them in an assembly-line style. Her product was so wildly popular, it sold all across the United States, even as far as the settlements in California.

“One of the first Valentines I ever bought has a line written on the bottom saying, ‘No, sir, I do not require your love.’”

“Esther Howland was the ‘Mother of the American Valentine,’” Rosin says. “American Valentines had existed before, but she made them more readily available. Her initial Valentines were small and usually marked with an ‘H’ and a number indicating the price or ‘N.E.V.Co.’ for her company, New England Valentine Company. But there are a lot of larger ones that were not signed that we now attribute to her. In 1850, she was the only person in Massachusetts who had access to these elegant European embellishments, and her Valentines had multiple layers of beautiful lace papers. You would lift one layer and then another and another. The message would usually be deep inside because she didn’t like to have you ‘wear your heart on your sleeve.’”

Rosin and fellow Valentine collectors believe Howland didn’t sign her largest pieces because they were embarrassingly lavish and expensive. “There is a story going around that she made such an elaborate Valentine in the shape of a May basket, and it might have sold for $50, which was the price of a horse and buggy at that time,” Rosin says. “We are told that the man was rejected because the woman said she would never marry anyone who would waste his money like that. So we’ve come to the conclusion that she probably avoided putting her name on the back of her fanciest Valentines. But we can’t guarantee that they’re her work.”

This 1860s scented Eugene Rimmel Valentine, lithographed with images of flowers and Cupid, folds out into a hand fan. A cord with tassels is attached to the bottom. (Courtesy of Nancy Rosin)

Across the pond, some of the most luxurious Valentines were being made by a French-born London perfumer named Eugène Rimmel, who exploited the upper class’ obsession with smelling good and avoiding the stench of London. Already boasting Queen Victoria as client, he impressed visitors to the Great Exhibition of 1851 with his elaborate perfume fountain. At theaters where the body odor of lower classes wafted up to the elites in the balcony, he handed out perfumed programs—featuring prominent advertisements for his Valentines and other goods—which let high-society ladies wave pleasant scents under their noses. At his shop on London’s Strand in the 1860s, he offered artful sweet-smelling music boxes, sachets, and mother-of-pearl fans, as well as scented paper Valentines. He hired a brilliant illustrator named Jules Chéret—who went on to become “the father of the poster”—to produce images of cherubs, romantic bouquets, and romantic heroines. Rimmel Valentines also came in the shape of fold-out fans, and he popularized the idea of giving paper gloves.

“Many of the most beautiful Valentines were made by Rimmel,” Rosin says. “He had shops in London and in Paris where he sold perfumes, and Valentine’s Day was one of his biggest moneymaking seasons. He had valentines for every theme, for every occasion, including themed cards based on Shakespeare or the Language of Flowers. Some of his Valentines had jewels like brooches attached to them; others were flowers hand-painted on silk. Rimmel also made beautiful chromolithographed almanacs for each year.”

In the United States, the devastating Civil War made love confessions even more urgent. Valentines from the period (1861-’65) show sweethearts parting ways or feature a tent where the flaps pull back to reveal a soldier inside. Lovelorn soldiers and their beloved would send one another locks of hair, as romantic messages and tokens of love gave soldiers motivation to return home safe. In the wake of the war, Americans, faced with unprecedented loss of life, became more sentimental, embracing Valentine’s Day as an opportunity to seize the day and honor the love they had.

This “moveable” postcard from 1911 has a heart with a kaleidoscope effect. With art by Ellen Clapsaddle, it was printed in Germany and postmarked in Philadelphia. (Courtesy of Nancy Rosin)

In the mid-1800s, technology for producing chromolithography and die-cut scraps became more widespread and affordable in Europe and the United States, which allowed publishers like Louis Prang, Raphael Tuck & Sons, Marcus Ward, and McLoughlin Brothers to mass-produce Valentine’s cards with beautiful illustrations—by the likes of Kate Greenaway, Walter Crane, Frances Brundage, Ellen Clapsaddle, and Maud Humphrey—and to cut these cards into interesting shapes like hearts. Printers also churned out thousands of lithographed die-cut “scraps” as the scrapbooking hobby gained popularity, particularly among women, who hoped to receive pretty Valentines they could paste into their books.

“After chromolithography became more widely available, around the 1860s, people could buy mass-produced Valentines that were appealing and reasonably priced,” Rosin says. “People’s lifestyles had changed after the Industrial Revolution. As they got busier, they became accustomed to buying things they had previously made by hand, which freed up some of their time.”

The expensive and time-consuming handmade paper confections, like the ones on which Esther Howland’s fortune was made, were going out of fashion. Paper Valentines lost the intricate, personal details that once defined them, and this, of course, led to grumbling about how Valentine’s Day had been ruined by Industrialization. But even then, beautiful things were being made.

“You began to get a lot of imports from Germany, because that’s where chromolithography was at its peak,” Rosin says. “German companies made Valentines with pop-ups including tissue-paper honeycombs that folded out into three-dimensional objects. The card imagery followed the new technology of the day, so you would have, for example, a steamship, hot-air balloon, dirigible, a modern roadster, or even an ‘aeroplane.’ It expressed to your beloved, ‘This is a magical new technology, and maybe if you choose me, this will be our future.’ In England, Raphael Tuck & Sons made some of these wonderful chromolithographed pieces, including mechanical cards with moving marionettes and climbers.”

This German Valentine from the late 19th century features die-cut pop-ups and honeycomb tissue paper. (Courtesy of Nancy Rosin)

Howland’s paper-confection business in Massachusetts was holding on until 1879, when she sold the company to a competitor, George Whitney. By 1888, Whitney had bought out at least nine other Valentine rivals in the United States. (Howland died in 1904 having never married, but she surely helped thousands of other couples to the altar.) Whitney’s version of Howland’s cards, as well as many created by the McLoughlin Brothers Company, “were mostly chromolithographed layers,” Rosin says. “Maybe there would be one lace layer and some embellishment, but they didn’t have the same luxurious feeling. Some are really beautiful, and some are awful.”

Valentine’s Day, then, sold out to machine-age commercialization almost 150 years ago, several decades before Hallmark arrived. But the Valentine-swapping traditions have lived on, through the 1900s’ mass-produced postcards, which have now become highly collectible, and modern folded greeting cards and card sets for schoolchildren, as well as lavish lover’s gifts of chocolate, diamond rings, and lingerie. According to the U.S. Greeting Card Association, currently around 190 million Valentines are mailed in America each year. Naturally, as the holiday has grown, so has the cynicism about it—some laugh at it, others shrug it off, and many flat-out call it a sham. Still, you have to wonder whether in the days when women eagerly awaited for the postman to deliver sentimental and scented lace Valentines, did those who waited in vain end up feeling shafted?

“Young people who didn’t receive any Valentines probably ended up heartbroken,” Rosin says. “I’m sure it must have been a very sad day. In one article in a newspaper from the 1870s, the author wrote, ‘I feel that Cupid must have an evil twin, because he inflicts so much pain.’”

(To connect with Nancy Rosin and the National Valentine Collectors Association, visit the group’s web site or Facebook page, and sign up for their newsletter, The Valentine Writer. See more antique Valentines at the Bodleian Library’s John Johnson Collection Pinterest page, co-curated by the NVCA. For further reading, pick Frank Staff’s “The Valentine and Its Origins”; Ruth Webb Lee’s “A History of Valentines”; Michele Karl’s “Greeting With Love: The Book of Valentines”; and Edna Barth’s “Hearts, Cupids, and Red Roses: The Story of Valentine Symbols.”)

Happy Valentine's Day, I Hate You

Happy Valentine's Day, I Hate You

Darling, Can You Spare a Dime? How Victorians Fell in Love With Pocket Change

Darling, Can You Spare a Dime? How Victorians Fell in Love With Pocket Change Happy Valentine's Day, I Hate You

Happy Valentine's Day, I Hate You From Whale Jaws to Corsets: How Sailors' Love Tokens Got Into Women's Underwear

From Whale Jaws to Corsets: How Sailors' Love Tokens Got Into Women's Underwear Valentines Day CardsSaint Valentine, a legendary ancient Christian said to have been persecuted…

Valentines Day CardsSaint Valentine, a legendary ancient Christian said to have been persecuted… Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

What a wonderful article. Thank you so much for sharing!

Nancy, as usual your article is full of history and love. Thank you.

I recently gave my 125th presentation about my valentine collection.

(Indiana and Illinois) My first was in 1976–forty years ago. My

audiences like to hear about the decades of the 1900s as they are

pictured on valentines…sentimental and comic–historical miniatures

of social history.

So many wonderful things to see. I am on my second time around. I found more that I didn’t see the first time. Thanks so much.

I found this site by accident, and it was my lucky day, and today is Valentines day. These are the most beautiful valentines I have ever seen.

You cannot find them in the stores today. Thank you for having this site put on the internet. I will read and keep reading these and I have put you in my favorites to keep up with these beautiful things of the past. I am almost 80 and I write some poetry, mostly for myself. Thank you again for this site. Eveyleen