Frank Maraschiello is the vice president of the 20th-Century Decorative Arts department at Bonham’s, New York. Recently we spoke with Maraschiello about Mid-Century Modern design, from George Nelson’s famous marshmallow couch to Eames chairs to the furniture of George Nakashima.

Mid-Century Modern used the technology of mass production to produce good-looking pieces of furniture out of the latest materials. A number of these materials became commonplace after World War II, so the idea was to make things affordable. These were not “custom-made pieces.” When you bought a Tiffany lamp, even though it was a production piece in its day, it was also handmade and cost as much as $500. That was a huge amount of money. It was not for general consumption. The Ruhlmann chair from the 1920s could cost as much as a house it went into. These pieces were made for the really, really wealthy classes.

That changed with Mid-Century Modern. Suddenly you had great architects and great designers designing for commercial companies, and middle-class people could afford to buy great design. I’m not talking about the watered-down 1930s American Art Deco that Herman Miller produced. Those pieces were quite nice, but to me, that’s not Mid-Century Modern at all. It was only the beginning of it.

There have always been utopian designers and architects who had this great idea that they’d be able to make wonderfully designed objects for the masses. William Morris tried it. Elbert Hubbard and Roycroft tried it. It was the Arts and Crafts idea that you could uplift the lives of the user with a thoughtfully designed and manufactured utilitarian object. I don’t know if this ideal ever really happened with Mid-Century Modern because I don’t know if the middle classes, the great proletariat, ever really embraced modernist design.

Collectors Weekly: How did Mid-Century Modern relate to the postwar culture?

Maraschiello: Mid-Century Modern is a really interesting product of the war. The war geared up all the manufacturing to produce at a record pace, and then afterwards they just retooled for civilian life. It was just astronomical how many people bought and consumed new appliances for their homes.

Collectors Weekly: What was the span of Mid-Century Modern, postwar until roughly the death of JFK?

Maraschiello: A little later than that. One very cool thing that people forget about JFK is that when he debated Nixon, they were sitting in Hans Wegner chairs. I knew the guy who produced the debate, and I asked him about it, and he said, “Yes, it was chosen because it was a very modern, iconic design.”

I think Mid-Century Modern went past the 1960s. When all the student revolutions happened in the late ’60s, people started to think outside the box. I think that was an interesting moment in time because there was an idea that maybe anything was possible. It was a revolution in design all over. You had all kinds of cool things happening, including this “socialism” of design, which has always been in the background of group design.

Collectors Weekly: So one aspect of the aesthetic was its collaborative nature?

Maraschiello: I think that people have always been aware of what other designers are doing; that there’s an aspect of collaboration and learning from others, even if it’s just new materials, even if it’s just ‘oh, look, so-and-so is using aluminum sheet on these tables’ in 1904. That’s a new material. It’s shiny and it doesn’t scuff. So people were always aware of new ideas that were coming forth.

Collectors Weekly: Did Mid-Century Modern fall out of favor in the ’70s and ’80s?

George Nelson rosewood and painted metal miniature six-drawer jewelry chest on stand. Image courtesy of Bonhams.com.

Maraschiello: No, it didn’t fall out of favor at all. More and more dealers were able to support themselves selling it, and more and more material came out. As more material came out, many of the people who had the stuff at home realized that all of this Herman Miller furniture they bought in 1960 was worth something. Say it was a Nelson jewelry cabinet: Now someone’s selling it for $8,000. “Do you believe that, Mom?” And Mom would say, “Wow!”

For the people who were buying these collectibles back then, they weren’t collectibles. When these things were bought it was just furniture.

I mean, Art Deco was only named Art Deco in retrospect, in the 1960s. The 1925 Paris Exhibition, the Exposition Internationale Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes, brought together the decorative arts and industrial modern techniques. It wasn’t called Art Deco: It was just what was contemporary for that age. What are the baby boomers going to be calling today’s design? It doesn’t have a name yet. It’s just our stuff.

Collectors Weekly: Who coined the phrase Mid-Century Modern?

Maraschiello: I don’t know who coined Mid-Century Modern, but it’s a great name. It’s a little wordy for some people, but everybody is always trying to put an umbrella name over things to create an easy name.

One of the earliest people dealing with Mid-Century Modern material was a man named Mark McDonald, who was one of the great dealers. He was in New York. He had a very, very important gallery called 50/50 on Broadway, but the gallery is long gone. I actually sold their last collection before the shop dispersed and the three partners went their separate ways. Some people say he was one of the first people to offer that material. Certainly in the early ’80s and late ’70s, there weren’t that many people selling it.

Collectors Weekly: What is it about the work of George Nakashima, especially the early pieces, that is of such interest to collectors of Mid-Century Modern?

The Slab Coffee Table from the 1940s was one of George Nakashima’s earliest designs. Photo source: nakashimawoodworker.com

Maraschiello: He is a crossover artist, I think, in the sense that it was what a lot of avant-garde creative people put in their houses after the war. He was a Japanese-American architect who was interned in the internment camps. He became quite a famous furniture maker. He used the natural grain and design of tree slabs. So you’re getting the beauty of the natural look of the wood as well as a philosophy beyond just the idea of making a piece of furniture. What he was interested in was revealing the beauty of nature. It was a reductive process to reveal the slab almost as God made it, perhaps.

It was certainly an acquired taste because at that point in time he was working in a different way than anybody else in America, as far as using the actual bark and the end of the tree. Even the fissures and various natural cracks that the slabs had in them, he found a way to buttress them using contrasting butterfly joints, often in rosewood. So he would be able to use a beautiful knot or a fissure in the wood. And it wouldn’t be a design flaw; it would become an added element of beauty to the piece.

Collectors Weekly: The other George of the period, of course, is George Nelson. What are some of the design characteristics that typify the classic George Nelson piece of furniture?

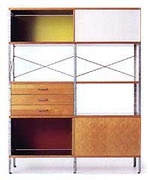

Maraschiello: There’s always a sleek look to Nelson. He’s got very strong lines, not tremendously ornamental. It’s usually a beautiful formed box with great proportions and lovely, slender legs that don’t take away anything from the overall design—they’re beautiful, elegant supports. There’s one whole series called thin edge. They’re not overly encumbered with an awful lot of extraneous molding and things like that.

Collectors Weekly: If that was his overriding aesthetic, where did the marshmallow sofa come from?

Maraschiello: There’s been a lot of debate about that. It’s probably one of the most whimsical designs ever to become an icon of American design, just because of the shape of the cushioning and such [see photo at top]. It is a little bit pop, and pop wasn’t even a word then. It is really about the interplay of shapes.

Collectors Weekly: How does Danish modern fit in to all this?

During their first presidential debate, John Kennedy and Richard Nixon sat in Hans Wegner PP 503 chairs. Photo source: PP Møbler, www.pp.dk

Maraschiello: The Scandinavians have always been off on their own, and they’ve always had a very good interest in design. Danish modern, I think, was not what we’d consider Mid-Century Modern. I think it was a bit later. They didn’t have the war-production issues that America and Europe had, and they were aware of new ideas coming out of Europe, even though they were tucked away in the north. They had a very rich design history themselves. They used unusual woods, too, but they did not have the access that some of the other countries had to rare, imported woods because they didn’t have many colonies. I always tell people that France, Italy, and England used unusual woods because they had access to them through the colonial system that was ending right around World War II. The Scandinavians were using teak, which they got through Southeast Asia because of trade agreements.

So most of the time, yes, the design geniuses in Scandinavia were doing very clean-lined things, but at the same time they were still producing traditional furniture there, like designers do everywhere.

Collectors Weekly: Were these so-called geniuses influenced by people like Nelson?

Maraschiello: The world was a small place after the war. I think they were off on their own, but they were aware. There are always furniture shows. For example, the Swedes showed in the 1925 Paris Exhibition. There’s always been unusual design going on up there. They’re a little bit off on their own tangent, but they’re aware. They go to the shows. They see what other people were doing. Scandinavia did have new design and furniture makers. They still produce arguably some of the best glass in the world. Some of Hans Wegner’s designs are still in production, 45 or 50 years later. It’s not just about Charles Eames.

Collectors Weekly: Speaking of Eames, can you tell us why the Eames chairs, both the plywood and the fiberglass versions, are so revered today?

A Ray and Charles Eames walnut and leather 670/671 lounge chair and ottoman. Image courtesy of Bonhams.com.

Maraschiello: The bent plywood chairs were a really, really clever idea, although bentwood was not new. At that point, it was a hundred years old. When they first found out how to bend pieces of wood, it started out with Thonet, who was the first to patent it in the 1800s. When the patent ran out about 1904, all sorts of other furniture makers got into the bentwood business.

When Eames came along, he was doing a very different thing, much more architectonic in its thinking. It was just a simple plane of wood for the seat and a simple plane of wood for the back, held together at first by iron and then by chromed metal. It was a simple, beautiful idea, with clean lines. The design flaw of that chair, according to certain people, was the rubber suckers on the back. The shelf life of the rubber is different than the shelf life of the wood. So depending on the humidity and the heat of where the chair was located, the rubber suckers holding the thing together would dry up and get brittle and break.

The Eames chair was easy to take apart. It was easy to ship. It was clean. It was stackable. It was portable. It was not a tremendous amount of mass. If you look at those two simple pieces of wood and that metal frame, all of a sudden you can put a 250-pound guy on it and it’ll still support his weight with very little mass of actual material holding him up. It’s not a miracle, but it’s certainly well thought out and it was certainly very well tested.

Collectors Weekly: And the fiberglass chair?

Maraschiello: The fiberglass was simply an extension, getting even more streamlined and getting even more, I think, faster in terms of its mass production because they’re molded. And I don’t know eventually what it got down to, how many chairs they could’ve produced of the bent plywood versus how many they could produce of the molded fiberglass in a day. But I’m assuming that it took quite a bit more time to produce the plywood chairs than the molded fiberglass ones.

The fiberglass was also a continuous piece. And I think that when it’s made in a metal mold like that, that those molds can go on for a very long time before they break down. So just from an economic point of view, it’s probably a lot more reasonable to produce fiberglass chairs than plywood ones. I don’t remember what the original selling prices of those were, but I think it was quite affordable.

Collectors Weekly: How does a company like IKEA relate to Mid-Century Modern?

Maraschiello: Well, I think IKEA took the idea of clean, streamlined furniture produced at a reasonable price and took it to an even more affordable level. But to get it that affordable level, they have to sacrifice some quality. So IKEA is a very good idea for certain levels of income, and it gives good, clean, simple, no-frills design with a sense of humor. You can still get great design, you can still get really interesting things from IKEA, and you don’t have to spend a great deal of money on it.

Some of them are knockoffs—there’s George Nelson written all over some of those thin-edge design cabinets and storage units. But not everybody can afford to buy Herman Miller or George Nelson.

Collectors Weekly: Who are we forgetting?

Maraschiello: I think we’ve touched on some of the great ones. There are always going to be favorites. People are always going to say, oh, you forgot this one or you forgot that one. But when people in the 1970s started looking back, the hot things to collect were Arts and Crafts, Art Nouveau, and, to a lesser extent, Art Deco.

“The Ruhlmann chair from the ’20s could cost as much as a house it went into. That changed with Mid-Century Modern.”

And then, after 20 or 30 years, the original houses that these things were in started to break up. People moved. All of a sudden, somebody who had a big house in 1960, with some Eames fiberglass, some Herman Miller pieces, and a couple of the Eames lounge chairs and ottomans, it all started coming out for sale because the house was being broken up. That’s when these things started to be more available on the secondary market.

Young dealers who were up and coming and were looking for something cool to sell picked up on Mid-Century Modern because it was unusual and available in good numbers. Of course, some people say that was one of the shortcomings of the market, that nobody had any idea how huge the numbers were.

With Mid-Century Modern design, the first time you see these things, you’ll either say, “My grandmother had that. I loved it,” or you’ll say, “Jeez, I remember that. I hated it!” And then maybe it starts to grow on you. We see both kinds of collectors. It’s a funny thing that happens. It’s doubtful that your children are going to be interested in holding and collecting anything that you collect. That’s just the way of the world.

Paper Wizard: Mid-Century Modern's Unsung Visionary Gets His Due

Paper Wizard: Mid-Century Modern's Unsung Visionary Gets His Due

Kem Weber: The Mid-Century Modern Designer Who Paved the Way for IKEA

Kem Weber: The Mid-Century Modern Designer Who Paved the Way for IKEA Paper Wizard: Mid-Century Modern's Unsung Visionary Gets His Due

Paper Wizard: Mid-Century Modern's Unsung Visionary Gets His Due Eames, Nelson, and the Mid-Century Modern Aesthetic

Eames, Nelson, and the Mid-Century Modern Aesthetic Pearsall FurnitureAdrian Pearsall (1925-2011) liked to make his furniture out of walnut so mu…

Pearsall FurnitureAdrian Pearsall (1925-2011) liked to make his furniture out of walnut so mu… Mid-Century ModernMid-Century Modern describes an era of style and design that began roughly …

Mid-Century ModernMid-Century Modern describes an era of style and design that began roughly … Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Pretty! This was a really wonderful article. Thank you for your provided information.

I was hoping you’d mention Ikea in this article. Yes, a lot of their pieces are clearly ripoffs of Mid-century Modern design. But beyond making this style of furniture affordable, it also created a lot more awareness and appreciation for Mid-century Modern. It’s a long-lasting — and growing — trend all over the world. And Ikea, in a way, has helped fuel that trend. As some Ikea shoppers acquire more money, they start buying the real pieces.

very good article Ben…..i love the first couch picture,,,very cool.

and to the person above who mentions Ikea….???

i sell old furniture….and Ikea….is so poorly made structurally…at the joints

i wont even try to resell them…cuz they fall apart so easily.

and it’s all made from press board that is not real wood,,,it’s glued sawdust.

Very interesting article . Ben .

*Sorry I see right now that this discussion is from April , 2012 .

I’m TOOO LATE .

I use to speak about Mid.Century-Modern for a year (2014) …

Ciao From Italy