Clifford Wallach talks about tramp art, noting its origins and social history, and addressing some historical misconceptions. Clifford has published two books on tramp art – Tramp Art, One Notch at a Time and his newest, Tramp Art, Another Notch: Folk Art From the Heart, available from Schiffer Publishing. He can be contacted via his website, Folk Art in the Tramp Art Style.

My first book, “Tramp Art, One Notch at a Time”, was self-published in 1998. At the time we started to do the book, it was just assumed that tramp art was made by tramps, but as we were examining the pieces, we started to see that it was more complicated than that. We started to find histories and biographies of some of the makers, and we started to move away from the idea of the tramp maker, this anonymous person walking through the countryside, making tramp art in exchange for food and lodging.

The heart is so prevalent in this art form, more so than in any other – even women’s textiles don’t have as many hearts as tramp art pieces do. We realized that it was much too intimate for a stranger to put hearts on pieces in exchange for food and lodging in Victorian times, the late 1800s.

Folk art is basically made by untrained common folk. It’s been around forever. We only started to appreciate it as an art form in the 1920s in this country, and they really focused on the weather vanes, rugs, quilts, sculpture. That’s what was revered. There were a few artists who were identified as makers but mostly it was an anonymous art form.

Tramp art was only discovered as an art form in the late 1950s. There was an article written by a Pennsylvania folklorist, Frances Lichten, in 1959 Pennsylvania Folklife magazine, and she identified the works. She was staying with some friends in Pennsylvania, and they had these pieces made out of cigar boxes. She was fascinated by it, so she did some investigating and sleuthing around and she saw other examples.

“There was more tramp art in places with long, cold winters; people didn’t have anything else to do.”

It’s called tramp art because of her article. One of the people she spoke to about the art form called it tramp work or something along those lines, and it had these tramp or hobo backgrounds, at least from this woman’s experience.

In the ‘50s, it was believed that any good folk art was made by these itinerate wanderers who pranced around the countryside. Since then, we’ve learned more about the histories of the carvers. Most of them have come away from the itinerate past. Tramp art, for some reason, was never investigated, and nobody did any serious scholastic research on the background makers until our first book came out. We identified historical makers, contemporary makers. There was this whole bevy of people, all around the world, making tramp art, wherever there were raw materials available.

Cigar boxes really drove the art form. Most tramp art pieces are made either using some or all of their components, the simple wooden cigar box, and that goes back to the 1860s. Cigars were the number one form of tobacco used in the 1860s. They were sold in big barrels and they’d put a little ribbon on it. You’ve seen the yellow ribbons and pillows and stuff. Those were from the cigars.

Cigars had to be sold in wooden boxes of a certain size, and once they were sold, you couldn’t reuse the packaging. The cigar manufacturers were actually box manufacturers. To sell the cigars, they felt they would use fine wood, because it would enhance the flavor and the presentation. They used fine woods, like mahogany and cedar. Once the cigars were sold, these nice boxes were discarded or sold for a few pennies. That’s what really drove the art form; the availability of this easily carved and nice wood.

Collectors Weekly: How did you get interested in tramp art?

Wallach: My great grandfather was a first-generation immigrant of this country. When he died, my mother got a cigar box filled with some dice, some cards, little knick-knacks that he collected throughout his life, and the cigar box still had that cedar smell from the wood.

My ex-wife was an interior decorator and she’d go to flea markets every weekend. At a flea market near my house, a guy had a thing he said was made out of cigar boxes. When I opened the drawer, that smell came back. It was just amazing. It wasn’t expensive, so I bought it. That was in the middle of the 1980s. We started traveling the world, looking for tramp art and buying as much as we could, and it culminated in my first book. Now all we do is buy tramp art.

The second book was very gratifying and it came out wonderful. But the story is still evolving. There are a lot of things we don’t know about the art form – where it came from, how it originated, how it just passed like a recipe from neighbor to neighbor and town to town – but I think that adds to the mystique. These guys were always celebrated. They were in newspapers and magazines. They won awards for their work. It wasn’t like they were ignored. It’s just that the antique community or the antique historians overlooked it or never really came in contact with it.

We buy and sell over 300 pieces a year, and we’ve been doing this for 12 years. There’s a lot of tramp art out there. We’re offered pieces every day, and we try to buy and sell a piece every day. That’s my motto.

We’re still discovering pieces from families. Most of the pieces are boxes. The easiest thing to make was a box because it’s from boxes, so you just use the box as the central compartment and you just build out to frames. People made their own frames. They probably made their own homes and furniture. And when Uncle Willie wanted to put his wedding picture on the wall, he built a frame for it the tramp art way.

It’s very prolific. There’s nothing like it. In folk art, the amount of boxes and frames in the tramp style dwarfed every other rustic or every other type of folk art frame made. There was a time from the 1870s to the 1940s that this was very popular, especially in this country. We’ve found pieces from Maine to Hawaii; anywhere where men smoke cigars.

During the 1870s through the 1930s, there were literally over a hundred million cigar boxes sold every year, so there was a lot of wood for these guys to use. Some were very good and probably made lots of pieces throughout their lives. What they liked to make was almost like their signature.

One guy made sunflower corners on all these frames. They’re identical. Other guys made lots of boxes in an identical fashion. It was like somebody said, “I’ll have one of these” – a neighbor or a relative or maybe even for trade or sale, who knows? But some people made one, and some people made them their entire life. It’s very interesting. Every piece is individual. We’ve never found any patterns.

The early writers on the art form – in the 1950s, ‘70s, ‘80s, and even today – erroneously stated that it came from European origins and certain craftspeople brought it to this country. It’s true that a lot of the makers were first-generation immigrants, but there were a lot of first-generation immigrants. We don’t see any age difference in the pieces.

If it started in a certain place or area, you would assume that there would be earlier pieces in one area, but on both sides of the Atlantic they’re basically the same age. We found earlier pieces here than we found in European countries. We’ll debate forever, which I think is part of the mystique about the art form – no one will ever have all the answers.

Collectors Weekly: How does American tramp art differ from European?

Wallach: In the U.S., the wood boxes were primarily free, and these guys were purists. They knew what they were doing. They used discarded materials. Simple tools like a pocket knife were really all they needed to make tramp art, and a bunch of the wooden boxes. The technique, the woodwork, and the styles differ a little bit because of the person making it, but I can more or less tell an American piece from a European one.

The Europeans used velvet a lot. They used brass embellishments. Sometimes there’d be German words. We tried to identify where the piece was made because each cigar box had to be stamped with the state and factory that it was made at so they could collect the taxes. So sometimes you’re able to identify a piece and a location based on the cigar box itself that they used.

But they weren’t copying. Sometimes folk art is copied; things that were hot in the decorative arts and so on. These guys were just carefree. Every piece is different. The reason they resemble each other was because the raw materials were the same. When you look at a cigar box, it’s six pieces of wood at the top and bottom, two longer sides and two smaller ends, so the pieces are similar looking because of the raw material.

They also used crate woods. In the 1800s and early 1900s, they used to ship a lot of the manufactured goods around the country by rail, and they would put them in thin wooden crates, usually made of pine. You see them for grapes and so on today. The crate wood was also easy to carve, and this allowed the tramp artist to make bigger things, like furniture and bigger frames.

Collectors Weekly: What’s the significance of the heart motif?

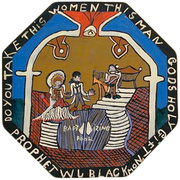

Wallach: The use of hearts was so important to the makers that it was the single most-used design element after the common pyramid or rosette. I don’t know why they called it tramp art if it wasn’t made by tramps. But the use of hearts has been central to discovering who made this and who they made them for.

To give you an example, most tramp art boxes were jewelry boxes or sewing boxes. They were love tokens. They were made for sweethearts or relatives or somebody that mattered. There’s nothing like it in any of the folk crafts, clothes – sculpture, fretwork. Nothing celebrates the heart as much as the tramp artist. It’s a touching story.

Collectors Weekly: Are there specific tramp artists well known for their work?

Wallach: Certain artists had a specific style that was like their signature, and we were able to identify a couple of men in the book that had significant bodies of work based on their style. There are pieces we can attribute to certain makers. Because it’s folk art and a lot of the collectors are used to anonymous artists, it’s more important for me, being a writer, to give some history and background to the art form. When I find a piece that’s signed, I celebrate it, but for most collectors it’s not as important. But we’re still identifying makers. It’s fun.

Most of the pieces were in industrialized areas like Pennsylvania where they had coal miners, and New York, but we find it everywhere, in every state in the Union. There was more tramp art in places with long, cold winters; people didn’t have anything else to do. It was everywhere, but it did appeal to a certain type of individual. They had to be busy.

Someone referred to it as men’s quilting. If you see a woman stitching, a man is notching. Some of the design elements are similar, stars and hearts and clovers and so on. I have some family remembrances where the grandmother was doing her sewing in the family room after dinner while the grandfather was doing his notching. It’s easier for people to visualize when they see these pieces.

Collectors Weekly: So this was a mostly male art form?

Wallach: Yes. In our new book, we identified two women who made tramp art and they’re fabulous, but we haven’t found any historical female makers.

The women made other things with cigars. There were little cards or silk things that were given out like trade stimulators, and they made quilts out of them. They made pillows out of the yellow cigar bands that were popular before there was a law to sell them in cigar boxes.

All the different crafts we celebrate today that were made at that time had patterns. They sold them in catalogs like Montgomery Ward and Sears. But we never found any for tramp art. It was just spread like a recipe, word of mouth, family to family, neighbor to neighbor, town to town, city to city, state to state, country to country, all around the world. We found pieces in Australia, South America, South Africa, and all of Europe.

The big difference that isolates tramp art in this genre of folk art is the absence of patterns, that it’s all individual. That we don’t have a ground zero where we can identify where it came from. We’ve identified over 40 different ethnic groups in this country who practiced tramp art. You didn’t have to have money. Everything was for free, and the only limit was your imagination or your skill.

I have a piece made by an Arab in 1919 for his daughter’s wedding and he enclosed her photograph on her wedding day. I have a piece with Jewish stars that had the Ten Commandments in Hebrew on a box. White, black, Asian – everybody was making it in this country. And when it’s good, it’s very good. It’s comparable to any folk art. It’s not crazy like these weather vanes that sell for hundreds of thousands of dollars. You could find a great example for a couple hundred bucks in good shape and over a hundred years old. They’re out there.

There are two main artists we’ve identified with bodies of work. One was John Zubersky and the other was John Zadora. They both made quite a bit and they were very talented makers. Zadora was from Pennsylvania, near the Allentown area. His piece was the very first piece identified as tramp art by that woman in 1959. He was in a prison, supposedly for not supporting his wife, and he made these heart wall pockets with birds and doves and horseshoes, all these wonderful things. But his history was forgotten as the generations that knew him died.

Zubersky was from Chicago, and we know a little bit more about his history. He would use shot glasses and coins to make his patterns, to make his elements, and he worked in a bar to get the cigar boxes for free. He was very prolific. He made mostly frames, and each one had over a dozen or so layers. Each layer had a different technique, and each corner of the frame had these glorious sunflowers.

Collectors Weekly: Besides just the boxes and the frames, what other objects are considered tramp art?

Wallach: It’s the style that makes it tramp art. It’s wood, it’s made in layers, and the outer edges of each layer are not carved. They made anything you could think of – furniture, frames, boxes, lamps, chairs. We just saw a full-sized bed and headboard, all tramp art style. They made their window sills in tramp art. They made shelves. They made miniature doll furniture for their children. Their only limit was their imagination and skill, and when they were good, they were very good.

Tramp art is still being made, and it’s because of these guys that I was able to understand much more. I don’t make it – I’m happy to buy it and put it on my wall – but through them, I was able to get the inspiration and understand more about how they arrived at certain techniques and so on and so forth.

Some contemporary artists are very conscious of the traditions and work strictly using the cigar boxes and pocket knives and glue and nails and so on. But most of these guys, if they had had power tools, they would have used them. To make tramp art in the 1800s and early 1900s, they would use glue or nails to keep the layers together. The glue they used was made from animals, and it had to be hot. They had to warm it up to make it adhesive. It was a very tough thing to do, and that’s also one of the reasons we realized that it wasn’t by vagabonds. It just couldn’t be.

Collectors Weekly: Who are some contemporary tramp artists?

Wallach: There are two women – Angie Dow and Frances Phillips. There’s Scott Lim, who’s an Asian-American whose father-in-law made it, and one of the best is Freeland Tana. He makes the most amazing stuff. It takes him years. He uses over a hundred thousand notches in every piece.

They still use found materials sometimes, but it’s much easier to get the wood now. Most of these guys are just crazy, and they use cigar boxes. The older cigar boxes are very brittle and hard to carve because they dried out, so they’ll use hobby wood. It’s already milled and so on for their projects. Some use wine crates, grape crates, things like that, which is in the tradition. It’s the completed object and how they did it that we’ll glorify.

I don’t know of any contemporary makers anywhere else in the world, but I assume if there was a historical connection, there are probably people still dabbling in it. It’s becoming more mainstream. People understand it better today than ever before. Every week somebody will e-mail me and say, “This was in my family. I saw my father make it. I have some pieces that were passed down in the family.” So we’re still discovering pieces, and people are a lot more familiar with it, especially with computers now. There’s a lot more information now than there was when I started. There was really nothing.

Collectors Weekly: What are some of your favorite items?

Wallach: They’re all my little favorites. I was on Martha Stewart, and I had a 6-foot clock, an 8-foot sideboard, and numerous 4- and a 5-foot frames, just trippy and big and huge. The last question she asked me was, “What’s your favorite piece?” So I got this little frame, probably 5 or 6 inches, highly decorated. As I’m talking, I realized that she didn’t understand because they told the camera people to get ready to shoot the clock or the sideboard as my favorite piece, and I pull out this little thing that I just bought. I got it yesterday. Look how great it is. I’m all excited about it.

Selling it is tough. I never thought I would ever sell a piece. The reason I can sell is because I’m buying more. It’s a great treasure. We have people that we sell to all around the country and Europe that and appreciate it.

It’s wonderful, and it’s not expensive. You don’t have to go to the bank to buy a piece, although the better, very rare pieces can be many thousands of dollars. But you can’t shop in your living room. We have to go out all day and weekends to different shows and flea markets.

Collectors Weekly: You find your tramp art at flea markets?

Wallach: Not as much. Mostly it finds me because I’m very visible and I’ve been doing this for so long. We still love going to shows and flea markets when we can. But if there’s a show in San Francisco, somebody who knows me, they’ll see something and say, “Cliff, there’s a great frame in this guy’s booth. Here’s his card.”

Once you recognize it, if you go to shows or shops, you’ll see it. When somebody sees our booth, they go, “Oh, my God. What is this stuff?” And I say, “Now you’ve seen it, you’ll find it.” Sure enough, they’ll come back to me maybe a year later and say, “You’re right. I have 10 pieces now.” That’s how it is. But it’s a nice fraternity of collectors – doctors, lawyers, Indian chiefs, bank presidents. When I first started collecting, it was mostly a male-dominated field. It’s dark and woody, but most of the pieces were made for women. A lot of the strongest, most passionate collectors are women.

Collectors Weekly: Why do people collect tramp art?

Wallach: I can only speak for myself. I love the sculptural look. I like the whimsical aspect. Every piece is different. I assume it’s similar with other people that collect. Our client base is over 4,500 people. People are thinking about it, talking about it, discovering it. We were very fortunate that Schiffer wanted to do a book on tramp art. It’s 270-some pages with over 600 folk art photographs. And we’ve been on Martha Stewart a couple of times. She mentioned the book a few weeks ago and the pieces and me.

I do think the hobby is growing. People that see it, love it, touch it, or are mystified by it. To me, every piece is a marvel. Although it’s similar to other pieces in form, shape, and style, it’s telling a story. Somebody made this. Somebody took his time to take apart cigar boxes and make plans, make a template, carve it up, finish it with shellac or varnish, and I’m holding it a hundred years later. To me, it’s amazing that these people had such talent and foresight and creativity.

Collectors Weekly: Do tramp art collectors tend to collect other forms of folk art as well?

Wallach: Yes, I think so. Folk art collecting is growing, and most collectors want a nice representative piece of tramp art in their collection. They don’t want a dozen pieces, but they’ll buy a few to complement their quilts and sculpture and weather vanes and so on.

There are people that collect just boxes. There are people that collect just frames. People who like painted pieces. But the better forms of tramp art are getting rarer. Most of the pieces are recycled from other collectors who bought them 20 or 30 years ago. When I started collecting, there were no specific dealers dealing in it. There were some people that seemed to find it, but it was just onesie, twosies.

What I would suggest is to buy framed boxes, things that are more unusual, in good shape. You don’t have to spend a lot of money. The way to really start is by getting things that you can afford and seeing what you like. If you like the boxes, if you like the frames, if you want to combine them. To me, tramp art is a lifestyle. We needed tramp art tables. We have our clothes in tramp art dressers. We look at tramp art mirrors. Our stuff’s in tramp art boxes. It’s a lifestyle. It’s more than just a collecting passion for us.

Collectors Weekly: Is there anything else you’d like to say about collecting tramp art?

Wallach: I love it to tears. It’s my whole life. It’s actually changed my life. I’ll never be tired of it. It’s just fascinating. The scary part is the more interviews I give, the more books I write, it’s not my little secret anymore. It’s going to be harder and harder for me to find good stuff, but I know nothing else so it’s everything to me. It’s a lifestyle.

(All images in this article courtesy of Clifford Wallach of Folk Art in the Tramp Art Style).

The Beautiful Chaos of Improvisational Quilts

The Beautiful Chaos of Improvisational Quilts

Homespun Beauty: Jim Linderman on Folk Art’s Authentic Appeal

Homespun Beauty: Jim Linderman on Folk Art’s Authentic Appeal The Beautiful Chaos of Improvisational Quilts

The Beautiful Chaos of Improvisational Quilts Teal, Merganser, and Other Antique Wood Duck Decoys

Teal, Merganser, and Other Antique Wood Duck Decoys Tramp ArtPopularized in the late 1800s and early 1900s, the term "tramp art" refers …

Tramp ArtPopularized in the late 1800s and early 1900s, the term "tramp art" refers … Picture FramesThough they might seem like afterthoughts, picture frames can be works of a…

Picture FramesThough they might seem like afterthoughts, picture frames can be works of a… Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Maribeth,

Nice article.We had no idea that you were involved with Collector’s Weekly.

Good luck with this and continue to spread the good word about “Folk”.

Ed.

I have a 19″house made with roll paper, looks like from pages of an old phone book.” The house has windows, doors that open and close, furniture, stairs, front porch and steps, hugh garage, two story.