Scott Vezeau with a portion of his trench art collection, 2021.

From the winter of 1914 to the spring of 1918, millions of Allied and Central Powers soldiers hunkered down within an estimated 35,000 miles of zigzagging trenches, from the Belgian city of Nieuwpoort on the North Sea to “Kilometre Zero” at the Alsatian-Swiss border. When these soldiers weren’t being exposed to mustard gas, sent into suicidal battles in the deadly no-man’s land between the opposing front lines, or struggling with the dysentery, typhoid fever, lice, trench mouth, and trench foot that were endemic to life in the trenches, they made art. Naturally, the vases, ashtrays, and other decorative objects they fashioned from spent brass artillery shells and other detritus of war were dubbed trench art.

“Every piece of trench art is a military souvenir, but every military souvenir is not necessarily a piece of trench art.”

It’s an inspiring story—we love it when the human spirit triumphs in the face of adversity—but if you’re picturing doughty doughboys painstakingly tapping out intricate designs on empty artillery shells while bullets whistle overhead, your imagination has gotten the better of you. In fact, only a fraction of the trench art produced during what was then called the Great War and what we now know as World War I was made by soldiers in the trenches, and of that fraction, the first wave of Great War trench art was mostly the handiwork of infantrymen who wore the uniforms of France and Belgium rather than the U.S. of A.

In this widely circulated “Official French Photograph” taken during the Great War, French infantrymen, known as poilus, make trench art from 75mm artillery shells. Although some trench art was certainly made inside the trenches, much of it was created in informal settings like this.

The goal of those French and Belgian soldiers had been simple: to create personalized mementos for their loved ones back home, tangible evidence that they were still alive. For these soldiers, spent artillery shells offered a variety of raw materials. The copper “driving” bands at the bases of shells could be transformed into bracelets for wives and sweethearts, while the aluminum fuse caps at the tips of the shells could be cut, carved, and polished into rings. The practice of making and receiving such intimate items proved so popular that by war’s end the French verb for “remember,” “souvenir,” had become a vernacular English noun, largely replacing the less evocative “keepsake.”

When the Americans joined the fight in the spring of 1917, entrepreneurial Allied artisans began producing trench art for their newly arrived brothers in arms, who had more money in their pockets than their European counterparts. Those Americans who arrived at the front with metalworking skills—thanks to the draft, there were many—were soon producing trench art of their own. After the Armistice of 1918, soldiers of all nationalities returned to their home countries weighed down with heavy, metal souvenirs, whether collected from the battlefield, handmade between skirmishes, or purchased for a few francs. Until at least the 1950s, Great War souvenirs made out of actual scraps of the Great War artifacts that still littered the landscape could be purchased near Ypres, Belgium. Site of five major battles, Ypres was and remains a popular destination for Great War tourists wishing to pay their respects to a fallen ancestor and bring home a piece of authentic—or at least authentic-looking—trench art.

These utensils were made after the Great War for tourists visiting battlefields, but they are still considered trench art because the handles, which are stamped with the names of famous battles, are made from the copper driving bands on artillery shells.

Scott Vezeau, a self-described “military guy” who joined the Army in 1984 before leaving the service in 2009 to begin a second career as a dealer of antiques and antique photographs, was drawn to trench art early. “My mom got me into it as a kid,” he says. “From the time I was about 10 years old, I liked military stuff. By 12 or thereabouts, my mom had bought me my first piece of trench art.”

As an adult, Vezeau educated himself about his childhood passion, citing Trench Art: An Illustrated History (Silverpenny Press, 2004) by the late Jane Kimball as one of the genre’s definitive works. “I like the way she talks about trench art,” he says. “For her, World War I was the golden age of trench art because a lot of it was produced during that war, and that’s where it got its name. But Kimball also puts trench art in context, citing examples of soldiers making things going back to ancient times.” In addition, Kimball details variants of trench art such as objects created by prisoners of war (sometimes used as currency for extra rations of cigarettes or food) and items produced by wounded soldiers convalescing in hospitals.

This working lighter is disguised as a World War I map satchel. It features the initials and serial number of a member of the American Expeditionary Forces.

For Kimball and Vezeau, the term “trench art” is fairly broad, although both draw a hard line at souvenirs that have obviously been manufactured from new material, which Kimball succinctly labels as “trench art style.” “I guess from my perspective and that of most of the trench art collectors I deal with, it’s accepted that real trench art has got to come from a piece of military debris or some sort of military part. That’s the starting point of trench art,” Vezeau says.

“The World War I pieces are some of the best I’ve seen.”

Mandating that a piece of trench art can only be called trench art if it’s made from the detritus of war suggests a spiritual dimension to the genre. “I always look at trench art from the perspective of the biblical verse about beating swords into ploughshares,” Vezeau says. “When you take something that once served a military purpose and transform it into either a utilitarian object like an ashtray or a decorative item like a vase, that’s trench art.”

Interestingly, that formulation leaves out a more recent, and highly popular, form of expression by military personnel, Vietnam-era Zippo lighters, which were engraved by U.S. troops during the Vietnam War. “Every piece of trench art is a military souvenir,” Vezeau says, “but every military souvenir is not necessarily a piece of trench art. If a lighter was made out of a bullet, then it’s trench art and a souvenir. But in the case of a Zippo that someone serving in Vietnam engraved, that’s just a souvenir.”

This example of post-World War II trench art appears to document the countries where an Army Nurse was stationed between 1944 and 1946. Vezeau believes it was made in Switzerland by a jeweler who had the tools to turn small spent artillery shells into souvenirs waiting for a personalized engraving.

Time can also be a starting point when identifying a piece of trench art, but it’s not as rigid and inflexible as you might think. “I wouldn’t say a particular piece is not an example of trench art because someone made it 30 years after the end of a war,” Vezeau says, “but most collectors prefer items that were made as close to the time period as possible. Some items are labeled ‘Souvenir of the Great War,’ so those were probably made after the war and sold to tourists, but during World War I, soldiers did make stuff during their downtime in the trenches; Kimball’s book has photographs of soldiers sitting in a trench, hammering away at artillery shells. From a collectibility perspective, that’s more desirable than a piece made for the big influx of tourists and families visiting the battlefields after the war, but I would still say the tourist piece is trench art.”

Defining trench art based on authorship can be more problematic. “One item might have a name engraved on it,” Vezeau says, “so that means it could have been made in a trench during the war, but it also could have been made during the occupation period after the war.” Or, it could have been a ready-made piece of trench art in a souvenir shop, awaiting only a name to be engraved before being sold.

This 14-inch vase made from a 75mm artillery shell features the name of the famous battle at Argonne, 1918. It’s lower half has been fluted.

Speaking of names, many trench art objects feature the name of a famous battle as a prominent part of their decoration. Normally, that would be a clue to an object’s creation, but without accompanying documentation such as a dated letter describing the creation of said piece, it can be next to impossible to know where and when an object was made, let alone by whom. Complicating the issue of authorship further is the fact that designs for artillery shells were available as paper or zinc stencils, which were sold to infantrymen and entrepreneurs alike. According to Kimball’s book, trench artists often used a dozen or more stencils on a single artillery shell, so while that certainly makes them artisans, that’s not quite the same thing as authorship.

Despite all these caveats, even the manufactured stuff Kimball labels as “trench art style” has its audience. “I really like trench art airplanes from both World War I and World War II,” Vezeau says. “I have some that were probably made in the 1930s from World War I bullets as kids’ toys. I like them, but they’re definitely different from the ones made during World War I. Nowadays, a lot of online sellers offer modern-made trench art jets, things like that. Those pieces don’t interest me in the slightest, but there is a collector market for them.”

The leaves and other designs on these 75mm Remington artillery shells from World War I were probably made using stencils, which were sold to soldiers and souvenir entrepreneurs.

For collectors who want the real thing, the most familiar type of trench art is the decorated artillery shell. Hundreds of millions of shells of all sizes were produced during the Great War—between April 1, 1917, and Armistice on November 11, 1918, France alone manufactured almost 150-million rounds of artillery ammunition. Of that output, 75mm artillery shells (the dimension refers to the width of the base, or about 3 inches) were especially common, so much so that soldiers referred to them as “75s”.

The reason for their ubiquity was the Canon de 75 modèle 1897, a 19th-century French-designed field gun that could fire as many as 30 shells a minute and was relatively maneuverable compared to German guns of a similar (77mm) size. By war’s end, 12,000 of these French guns were in the field, which stoked the demand for 75mm ammunition. While the spent brass shells were intended to be melted down and made into new live ones—salvage crews were a key part of military support forces—there were plenty of discards to go around.

In the course of researching the engraved name on this vase, Vezeau learned that LT E. B. Thorsen was a member of the 127th Infantry, 32nd Division. This shell features an engraved reference to the battle at Alsace on May 21, 1918. On July 3, 1918, Thorsen gave his life near Roncheres, his heroism earning him a Distinguished Service Cross.

The transformation of artillery shells from war debris to something you might want to put on the mantel and fill with flowers did not come easy. After all, the shells were made of brass, an alloy of copper and zinc that has been prized since ancient times precisely because of its hardness. That presented a problem for soldiers in trenches, which is why most examples of objects that were actually created in trenches were not trench art as previously defined but souvenirs made of wood or bone, either of which could be carved with a common pocket knife.

Consider the challenge brass posed to the aspiring trench artist: To begin, the shells had to be heated to make them malleable. Though brass is typically brought to a temperature of around 1,500 °F for forging, a good wood fire will hit 1,100 °F or more, which is hot enough to soften or anneal the material, making it easier to work while simultaneously protecting it from stress cracks caused by constant hammering.

Rifle shells, bullet heads, German coins, and a button from a German uniform are the main parts used in this trench art dollhouse furniture.

In the trenches, the tools required to etch, engrave, emboss, flute, and flare an artillery shell were primitive. Although ball peen and other types of hammers were common enough, the fine tools on the receiving end of each hammer blow were not. Accordingly, infantrymen regularly resorted to nails, straightened bedsprings, and screwdrivers to produce their designs. Eventually, as trench art took off, Allied soldiers purchased fancy embossing punches in Paris to achieve the designs specified on some of the trench art patterns that were also available for sale.

Embossing was so hard on the artillery shells that in addition to repeated annealing, the shells had to be filled with sand, or even lead, to keep them from cracking or deforming while being worked. Fluting, in which vertical indentations were either pounded into the sides of a shell by hand or formed by running a shell through the unyielding gears of a field gun, was even more brutal. Sometimes a fluted shell was heated and then twisted at the flutes to create a spiral effect. Regardless, if a shell was to feature fluting, that work was completed before the trench artist decorated the rest of the piece via engraving or embossing.

This tiny (it’s only 1 3/8″ in diameter) inkwell made of scrap brass and copper features a British General Service button on its hinged lid.

In a class by themselves are the tops or openings of the shells, which were scalloped, rolled, pinched like pie crusts, flared, or cut into shapes like thistles, oak leaves, and French fleur-de-lis. In some cases, the tops of trench art vases were rolled, flared, and then woven with wire, giving these pieces a basket-like appearance.

Given the heat and hardware needed to execute all of these decorative touches, it helped to have access to serious tools, along with the skills to wield them. During World War II, many very fine examples of American trench art were made by Navy Construction Battalions, whose units and personnel were known as Seebees. “They had all sorts of equipment to build beachheads, airfields, and docks, so they had all the tools they needed to make trench art items,” Vezeau says. “I’ve seen a number of postwar yearbooks produced by Seebee units highlighting what they did during the war; in some of those yearbooks, there are photographs of trench art made by the guys in the Seebee repair shops. They would sell their work to sailors and soldiers who were in the area.” Sound familiar?

A World War II trench art ashtray from the Pacific Theater, depicting a P-38 with aluminum wings and tail. The cigarette rests are made of Australian coins dated 1944.

Still, when it comes to trench art, machine shops and modernity do not necessarily equal higher quality. “The World War I pieces are some of the best I’ve seen,” Vezeau says flatly. “There were a lot more metal workers back then,” he explains. “If I’m a candlestick maker in Belgium in 1914 and I can’t serve in the Army, I don’t have a job. So, I make candlesticks out of artillery shells and sell them to the soldiers who pass by.” Jewelers and watchmakers also pivoted to trench art. “Some of the engravings on the World War I pieces are just phenomenal,” he says.

(To see more of Scott Vezeau’s collection of trench art, antique photographs, and other items, visit his Show & Tell page. If you buy something through a link in this article, Collectors Weekly may get a share of the sale. Learn more.)

Copper Chronicles: How a Shipyard Worker Hammered Artillery Shells into Art

Copper Chronicles: How a Shipyard Worker Hammered Artillery Shells into Art

Women and Children: The Secret Weapons of World War I Propaganda Posters

Women and Children: The Secret Weapons of World War I Propaganda Posters Copper Chronicles: How a Shipyard Worker Hammered Artillery Shells into Art

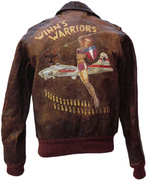

Copper Chronicles: How a Shipyard Worker Hammered Artillery Shells into Art WWII War Paint: How Bomber-Jacket Art Emboldened Our Boys

WWII War Paint: How Bomber-Jacket Art Emboldened Our Boys Trench ArtStrictly speaking, trench art is a phrase that describes folk art created b…

Trench ArtStrictly speaking, trench art is a phrase that describes folk art created b… Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Great article!! Love the how it’s made information. Now all that is missing is a price guide.

Amazing story ! I went to a Estate sale in the Oakland hills several years ago and the gentleman had literally several rooms packed with trench art.

Trying to find imformation about iron work. By hetherton & best

Why did American servicemen in WWII inscribe names and Serb I’ve numbers on back of Australian coins?

I have a piece not sure what it is we think it might be trench art and I have a pic I like to share

I have looks like beer sten it’s made out of a old artitary shell n mark 1915.i wish I could sens you a picture of it.

Bought this helicopter with one stamp on bottom which looks like kf2 53. Always thought it was trench art but now that I’ve seen the stamp I’m not so sure.

I have an copper ashtray. It’s ‘peppered’ hammered with a square pointed tool, with a depiction of a German Iron Cross in its centre. Around the edge in German is stamped “GRUHS AUS FRANKREJCH WELTKRIEG 1914-18 (translated I think is) “Greetings from France World War 1914-18” the lettering is struck with letter dies. Now I’m presuming this is made after the war since it has a end date? Would this be considered trench art…or tourist trappings?

I have several vases all marked 1946 but i was told it was from viet nam is this possible?