On a decrepit block of Broadway in downtown Los Angeles, hidden behind a dilapidated, aging façade, lies the ghost of a palatial dining hall filled with towering redwoods and a gurgling stream. Known as Clifton’s Brookdale Cafeteria, this terraced wonderland recalls a different time, when cafeterias were classy and downtown living was tops. Against all odds, the Brookdale outlasted attacks from notorious L.A. mobsters and decades of neighborhood decline. Over the last few years, Clifton’s has been closed while staging its comeback, finally being restored to its original Depression-era grandeur [Update: It closed again in 2018.]

“At its height, the Brookdale could seat up to 15,000 people a day. No other restaurant on Earth could do that.”

As the last jewel of a 20th-century cafeteria empire, the Brookdale’s unique vision of paradise has earned a spot in the hearts of many longtime Angelenos. Real-estate developer and entrepreneur Andrew Meieran, the restaurant’s current owner, says he was first drawn to the idea of rehabilitating Clifton’s almost a decade ago, enticed by its quirkiness and his disbelief that it was still in operation. “I just became fascinated by it. It’s this wonderful link to old L.A.,” he says.

The overhaul of the Brookdale restaurant, which Meieran began after purchasing it in 2010, is meant to restore many of its original details while also updating the business for a more modern L.A. “We’re bringing Clifton’s back to the way it originally was, to be the center of the community,” says Meieran. “It was a place where everybody could meet, a place that fueled artistic passions. You had everyone from Jack Kerouac to Ray Bradbury eating here. People were inspired by this complete fantasy environment.”

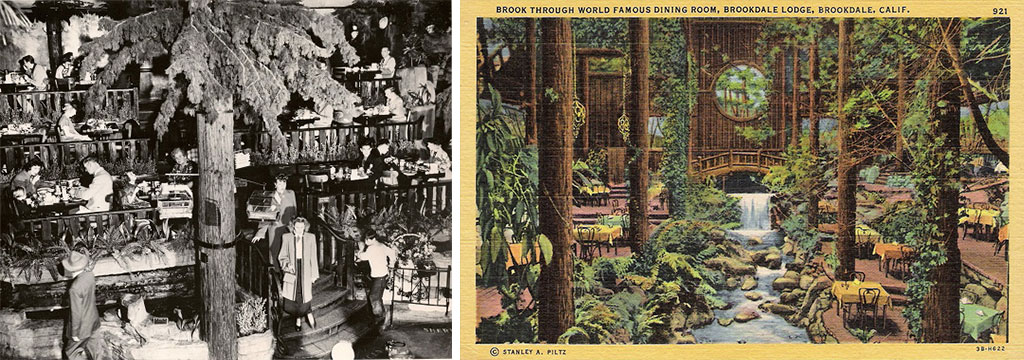

Top: The exterior of the Brookdale cafeteria during its early years. Above: The Brookdale’s main dining room in all its woodland glory.

Clifford and Nelda Clinton opened their first restaurant in 1931, on the site of a run-down Boos Brothers cafeteria at 618 Olive Street, naming it Clifton’s by combining Clifford’s two names. “It was during the height of the Great Depression when we came to Los Angeles from Berkeley,” explains Don Clinton, Clifford Clinton’s son.

“My dad had grown up in San Francisco, working with his father in the Clinton Cafeteria. He sold his interest to his brother-in-law and cousin, and moved south because his ideas were a little more liberal, exotic—progressive even. Dad wanted to feed people even though they couldn’t afford it. If they were hungry, they’d be welcome just the same.” In the thick of the Depression, Clifford Clinton built his restaurant as a place of refuge for those unable to afford a hot meal (one of the neon signs out front read “PAY WHAT YOU WISH”). Soon after the first Clifton’s opened, customers began referring to it as the “Cafeteria of the Golden Rule.”

Having grown up in a family of strong Christian faith, Clinton was taken on family missionary trips to China, and was profoundly affected by the poverty he witnessed. “As a boy, my dad spent time in China on two different trips with his parents,” Don says. “The last trip was when he was 10 or 11 years old, and he saw so much starvation—mothers trying to feed their children by giving them roots or mud to fill them up. Dad was so impressed that he vowed if he were able, he would feed people who were hungry. That was his motivation, the feeling that we were put on Earth to do something good for others, and he carried that theme pretty much throughout his life.”

A recent view of the Brookdale interior, including a neon cross on the roof of its small chapel. Photo courtesy Jesse Monsour.

In an era when profit-oriented businesses often attempt to cast themselves as philanthropic ventures (see the conceit of certain internet entrepreneurs, or delusional luxury retailers like Restoration Hardware), Clifton’s original mission comes as a breath of fresh air. At the Clintons’ second restaurant, the Penny Caveteria—named for its basement-level locale—meals cost only one cent. They were free if you used one of Clifton’s redeemable tickets, which were frequently given out to the homeless.

Long before the Civil Rights movement allowed black Americans to freely patronize white-run establishments, Clifton’s restaurants were integrated. In response to a complaint about his progressive policy, Clinton wrote in his weekly newsletter, “If colored skin is a passport to death for our liberties, then it is a passport to Clifton’s.” Regardless of income or skin color, Clinton wanted everyone who ate at his restaurants to be completely satisfied, so the phrase “Dine free unless delighted” was printed on every check. Though many patrons ate for free, enough customers gave significantly more than they were asked to keep the business afloat.

“The Clintons were true missionaries, in that they wanted to show by deed and example, and did a fantastic job with it,” says Meieran. “They offered self-improvement classes; they provided a barber and ways to clean up if you couldn’t afford them yourself. It was all about the community and providing help, as opposed to just making money. That was never the goal.” Working with local doctors and pharmacists, the company created a fully paid medical plan for its staff. After surgery or a hospital stay, recuperation was provided in the sprawling Clinton family home in the Los Feliz neighborhood of L.A.

Eventually, one of the Caveteria’s regular patrons offered Clinton the chance to open a location in his building at 648 South Broadway. In 1935, this spot would become the Brookdale, the largest cafeteria in the world. Only a few years after opening the Brookdale, the Clintons redesigned the space as a lavish distraction from the country’s financial hardships, with an over-the-top themed environment that made it one of L.A.’s new hotspots.

The Brookdale’s interior was inspired after California’s great national parks, with columns made from actual redwoods, rocks and foliage bursting from the walls, and a stream running right through the dining room. “It was copied after Brookdale Lodge in the Santa Cruz mountains not far from Felton, California,” Don explains, referencing a Prohibition-era hotel whose Brook Room was built around live redwoods and a running stream. “My dad spent a lot of years around there as a boy, and he loved those redwoods, so he wanted to replicate that as interior décor.”

Clifton’s forested dining room, left, was inspired by the grand hall at the Brookdale Lodge in Brookdale, California, where Clinton spent time as a boy.

Today, it’s hard to imagine cafeterias as groundbreaking, since they’re now known for drawing the senior-citizen crowd with bland, overcooked food and hospital-style furnishings. But in the 1930s, cafeteria dining was a completely modern innovation, representing the freshest fare available.

“If colored skin is a passport to death for our liberties, then it is a passport to Clifton’s.”

“The cafeteria was a very European idea, and it grew out of the Scandinavian smorgasbord, brought to the United States in the 1880s,” explains Meieran. “Cafeterias originally served top-end, high-quality food because their money was spent on the product instead of the service. Since people were serving themselves, they didn’t have to pay the wait staff as much, so they could spend more money on food.

“In addition, it had to be good because it was actually out there in front of you, and customers would never pick items if they looked or smelled bad. On a normal restaurant menu, you don’t have any idea what you’re going to get until it finally arrives. But in a cafeteria, the food is right up front and personal. And if it don’t look good, you ain’t gonna buy it.”

According to Meieran, the standard Clifton’s menu has changed significantly since the company’s birth. “I actually found all the original recipes for Clifton’s, all the way back to the opening,” Meieran says. “In fact, the recipes go back to the family’s cafeterias in San Francisco, in the late ’20s. It really began with much more extensive, high-quality, eclectic fair. I have pictures of Clifton’s in the 1930s, when they were serving lobster, whole lobsters. They had them all laid out, they had cracked crab, and this whole raw bar. It was beautiful, just incredible.”

“Cafeterias became the original fast food,” he adds, “and they allowed people to time their days better, instead of worrying if they’d be served quickly at a normal restaurant. It was the first real convenience food. The other big factor was that you could serve many more people: At its height, Clifton’s Brookdale location could seat up to 15,000 people a day. No other restaurant on Earth could do that.” Besides their forested main dining hall, the Brookdale also included a tiny, two-seat chapel for spiritual reflecting plus a separate top floor with a more traditional, red-and-white interior.

The Brookdale was such a success, the Clintons decided to give their original restaurant a makeover, transforming it into the Pacific Seas in 1939—a tropical wonderland filled with waterfalls, palm trees, neon lights, tiki furnishings, and a Rain Room, where a fake thunderstorm occurred every 20 minutes. Clinton called the restaurant “a poor man’s nightclub.” Never one to overlook their religious commitments, the Clintons paid homage to the biblical Garden of Gethsemane in a small basement room.

Clifton’s over-the-top interiors also had influential admirers. “Welton Beckett, who designed the original Brookdale, was best friends with Walt Disney,” says Meieran. “Several people who knew him said that Disney went to Clifton’s and was inspired by the design. There had already been fantasy architecture, but Clifton’s took it to a new level.” Disneyland, the pinnacle of fantasy environments, wouldn’t open for another two decades.

A late-1940s postcard shows the waterfall-facade of Clinton’s Pacific Seas restaurant with its iconic signage.

Even as Clifton’s was succeeding via the family’s idealistic efforts, the city of Los Angeles was awash with corruption, particularly following the election of Mayor Frank Shaw in 1933. Instead of taking a cut and turning a blind eye to organized crime as previous politicians had, Shaw streamlined the city’s mob rackets, thereby increasing his own payoff. Along with his brother, whom he appointed secretary, Shaw began selling off city appointments and set the going bribe rates for illegal activities like prostitution and gambling.

Clifford Clinton never had his sights set on politics, but in 1936, a city supervisor asked for his opinion on the food-service problems at L.A. County General Hospital. True to his nature, Clinton performed a detailed inquiry that revealed huge misappropriations, resulting in the dismissal of the hospital director. The following year, Clinton joined the county Grand Jury as chairman of a committee to investigate vice. Using his customer base as a huge insider network, Clinton tipped the jury off to L.A.’s widespread corruption, demanding a thorough investigation. Only when they ignored his request did Clinton realize how deep the corruption really ran.

“There was quite the gangster element coming in from the east and becoming more established,” says Don. “Once dad was on the grand jury, he had a badge and credentials to push for change. There were lots of protected houses of prostitution, gambling, and other things that were clearly against the law, but many of the police were being paid off to just wink at that.”

“There had already been fantasy architecture, but Clifton’s took it to a new level.”

Not only was the mayor’s office in on these shady dealings, but the local news conglomerate, controlled by the Chandler family of the “Los Angeles Times,” plus District Attorney Buron Fitts and Chief of Police James E. Davis were all part of the plot. People who attempted to expose their nefarious behavior were blackmailed, or sometimes just murdered.

Yet Clinton didn’t back down. Instead, he filed a minority complaint to the grand jury and established the Citizens Independent Vice Investigating Committee (CIVIC). Clinton soon had evidence of nearly 600 brothels, 1,800 bookies, and 300 gambling houses. In response, his businesses were suddenly attacked: Notices for phony sanitation violations and false taxes were delivered, new permits were denied, stink bombs were left in kitchens and bathrooms, food-poisoning complaints poured in, and buses full of supposedly “undesirable” customers were dropped off at the cafeterias’ entrances.

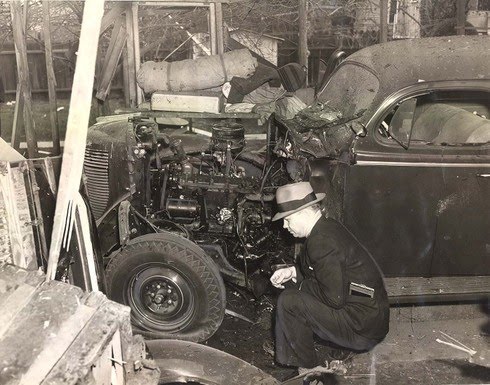

Things quickly went from bad to worse. In October, a bomb was detonated in the kitchen of the Clinton home. “It was just a couple of days before Halloween in 1937,” says Don, “when the corrupt elements of the police department put a bomb under our house. I was about 11 or 12, and I was sleeping with my brother and sister on the outdoor sleeping porch. The bomb was supposed to be a warning that our dad was getting too close trying to uncover all this corruption in Los Angeles.”

Luckily, nobody was hurt, but only a few months later, a car-bomb critically injured former police chief Harry Raymond, who was working as an investigator for Clinton’s CIVIC group. Shortly after, the director of LAPD’s Special Intelligence Unit was arrested for the crime when bomb parts and other evidence were found at his home.

Clinton still wanted to take down Shaw, so he pushed for a mayoral recall. Despite being blocked from all major news outlets, he found a small radio station that would broadcast CIVIC’s findings four times a day. “My dad finally initiated a recall movement, the first recall of a big-city mayor in America. It made a lot of ripples,” says Don. Though mob bosses tried everything to slow the campaign, Clinton gathered the necessary signatures, and the city overwhelmingly supported his new candidate, Judge Fletcher Bowron, who got nearly double the votes Shaw did.

After winning his war against the Shaw regime, Clinton began working with Dr. Henry Borsook, a biochemist at Caltech, to create a cheap meal supplement to fight hunger. “He went to Caltech in the late ’30s to develop this food product using a derivative from soybeans,” says Don. Borsook’s research led to Multi-Purpose Food (MPF), a high-protein supplement that cost only three cents per meal. Clinton went on to found Meals for Millions in 1946, which eventually produced and distributed millions of pounds of MPF to relief agencies around the globe.

The Clifton’s Cafeteria in this West Covina, California, shopping center featured Googie-style signage.

By the late 1940s, Don had taken over the Clifton’s business with his brother, Edmond, and his sister, Jean, and they continued expanding their cafeteria empire to 11 different locations in Southern California area. As Meieran explains, the décor was no longer limited to kitsch. “One was a sort of European garden, and another one was an Etruscan villa-esque place,” says Meieran.

“There was a very space-age, modern Clifton’s fitting with the whole Googie-architecture style. A couple were very small, and those didn’t really have themes. But Clifton’s Silver Spoon location is a good example: Before, the building had been an old jewelry store, so the Clifton’s interior utilized the existing architecture and location in the Jewelry District, repurposing the jewelry cabinets as display cases.”

The Brookdale building was originally constructed in 1904 as a furniture store, signs of which contractors discovered during the most recent renovation, like a column painted with directions to different store departments. Though the restaurant has undergone alterations every few decades over the last 80 years, many interior elements remain virtually unchanged.

In fact, Meieran’s crew discovered a neon light sealed within the walls, likely powered continuously since 1935. “It was embedded like 8 inches into the wall, and closed in with a piece of plywood and then sheetrock and tile,” says Meieran. The six rows of neon tubing were originally installed to backlight a painted woodland scene in the basement restroom, and then accidentally walled-over in 1949 when part of the space was converted to a storage area.

“The 1960 renovation was when they covered the old façade, and tore out a lot of the interior elements,” explains Meieran. “They painted the woodwork battleship gray and white. They took out the old water wheel and the old wishing well.”

During its prime, the Brookdale was located in the busiest neighborhood of the biggest boomtown on the West Coast, but L.A.’s vast suburban expansion and crumbling transit infrastructure hit its downtown hard. “From the mid ’50s, it started declining, and by the time you get to roughly 1965, development was in full retreat,” Meieran says. “L.A. had an unlimited amount of space at the time: You could build all the way to the beaches in every direction, and to the desert in the other side. And you had all these different centers—places like Century City and parts of Santa Monica and Beverly Hills were booming.

“People and industry started leaving the old-school Financial District because it was too far, a bit dirty, and there were more homeless people. And as traffic got worse, it was harder to get here, and of course, they took out the bloody transit system. By the time you’re in the mid-’60s, downtown was no longer the city’s center.”

The bustling neighborhood around Clifton’s Brookdale (second building from the right), seen in its 1930s heyday.

Even with its wild interior décor, the Clifton’s chain was still hit hard by shifts in the food industry, and the Pacific Seas location became the first branch to close in 1960. Clifford Clinton passed away in 1969, but his children kept the restaurants going as long as they could. “As leases ran out and fast food took away more and more of the youngsters, cafeterias became a little passé, and we just got down to the final one on Broadway,” Don says. Today, the Brookdale sits like a bizarre time capsule on a block of fast-food joints, cheap electronics stores, and signs reading “CASH 4 GOLD.”

So how did the Brookdale manage to survive these turbulent times? “It was such an incredible concept and so well executed that the Brookdale maintained itself through a lot of inertia and public goodwill,” says Meieran. “They also adapted to a different economic environment as downtown shifted to a different demographic. They started catering to the neighborhood by lowering the quality of food and lowering their prices, or at least maintaining prices when everything else went up. When we bought the place, it still serving 25-cent coffee, in an era of $3 or $4 coffees. But the quality was commensurate with 25-cent coffee. It was a great place that was slowly evaporating.”

Left, a lighted menu board displays standard Brookdale fare, and right, the building’s exterior as it looked post-1960. Photos courtesy J. Eric Lynxwiler.

“I think its reputation and ambiance and unique décor were all pulling factors,” Don says, though he admits that toward the end, much of the clientele was made up of lifetime supporters rather than new customers. “Young people didn’t like cafeterias because they had enough of cafeterias, either in the military or in school, and they didn’t care for them very much.”

Whether or not it was hip to eat there, the Clinton family managed to keep meals available to those who couldn’t afford them throughout the Brookdale’s many decades of operation. “We tried to keep that up until the very end. In honor of my dad’s commitment, we felt that it made good sense, and it was the right thing to do, giving back to the community that’s supporting you and having empathy for the down and out. It always worked out.”

Left, the Brookdale’s original facade was revealed during renovations in 2012. Photo courtesy J. Eric Lynxwiler. Right, most recent diners at the Brookdale had been lifelong fans. Photo courtesy Jesse Monsour.

Meieran hopes that the current rehab of the Brookdale will draw in a younger generation, as they bring back many original features and even add some new, over-the-top designs. “Clifford Clinton always described it as a forest oasis in the urban jungle,” says Meieran. “We’re going to expand that to include parts of the Pacific Seas and other thematic elements, but I would say it’s an urban fantasy night-life spot and restaurant. The idea is to reinvent and reinvigorate the cafeteria.”

As for the menu, Meieran calls it a “contemporized version of classic cafeteria fare.” In addition to standard comfort foods like macaroni and cheese, Meieran wants the broad nature of his cafeteria’s menu to reflect the eclectic cultures that make up Los Angeles, ranging from Chinese food to Mexican dishes. That should go over well with the Brookdale’s longtime customers, as Don remembers enchiladas being a top seller, moving more than 1,000 orders during an average lunchtime.

Despite several delays, Meieran says the new Brookdale, in some form, will be open within six months. “Almost daily,” he adds, “I am blown away by its history, by its infrastructure, by these weird, little, quirky things, or by the people that come out of the woodwork and say, ‘I went with my grandmother in the ’40s.’ When I first got involved with the restaurant, there was a guy who was 101 and had been at the opening of Clifton’s in the ’30s, and he was still coming in once a month, always walking in on his own power. The barrage of stories is astonishing.”

The Brookdale’s colorful terrazzo sidewalk. Photo courtesy Chris Jepsen.

(Special thanks to Chris Jepsen, Jesse Monsour, and J. Eric Lynxwiler for the use of their images.)

Dreams of the Forbidden City: When Chinatown Nightclubs Beckoned Hollywood

Dreams of the Forbidden City: When Chinatown Nightclubs Beckoned Hollywood

Making, and Eating, the 1950s' Most Nauseating Jell-O Soaked Recipes

Making, and Eating, the 1950s' Most Nauseating Jell-O Soaked Recipes Dreams of the Forbidden City: When Chinatown Nightclubs Beckoned Hollywood

Dreams of the Forbidden City: When Chinatown Nightclubs Beckoned Hollywood Neon Lost and Found: Where New York City Still Burns Bright

Neon Lost and Found: Where New York City Still Burns Bright MenusBefore restaurants had printed menus, dishes and prices were written on cha…

MenusBefore restaurants had printed menus, dishes and prices were written on cha… Restaurant WareRestaurant ware, also called hotel china, refers to plates and bowls, cups …

Restaurant WareRestaurant ware, also called hotel china, refers to plates and bowls, cups … Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

I wanted to know if there are any records or photos of the chiefs that worked at the Clifton’s on Broadway in DTLA. I was told that my Great Grandfather Thomas Sanchez was one of the long time chiefs that worked there in the 4o’s. Looking forward to the new Grand Opening.

Frank

Hi Frank,

The LA Historical Society recommended checking out the UCLA Special Collections Library or the Historical Society of Southern California. I didn’t come across many images of the Clifton’s staff on the web, so you might want to try calling those organizations to start with…

Cheers,

Hunter

………Great article, Clifton’s must have inspired many restaurants during his time.

Most shocking is to see how hard he fought corruption, unlike the clintons of today.

Looking forward to Clifton’s returning to the #DTLA landscape with all the food “upfront and personal” for a new generation! Cheers!

Very good to learn of both Clifton’s entrepreneurship and his generosity in passing his good fortune on to feed those who could not afford. Very admirable to see his returning some of what he earned from the people to the people and doing his best to help through public service as well. One of the Angels of Los Angeles. Well done, Mr. Oatman-Stanford!

I’ve been excitedly awaiting the reopening! Is there any plan for publishing a cookbook from the old recipes? How about republishing the gorgeous old postcards, or publishing new ones?

I have eaten here many times starting in the 1940’s. (Maybe before that but the 40’s is what I remember) It was always a must when we took the 5 car from Inglewood to LA. Shopping then to Clifton’s. The food was wonderful and we always ate more than we should. I didn’t know about the other Clifton’s but for me there will only be ONE Clifton’s and that is the one in downtown LA. What great memories.

This is wonderful. I’ve got to figure a way to work it into my vintage novel. I love this and would love to go there. The terrazzo still looks great. I will share on my FB and twitter! Wonderful and GREAT site!

~ Tam Francis ~

http://www.girlinthejitterbugdress.com

Great article Hunter. Here’s a part of the Clifton’s story you may not have known: http://www.laweekly.com/publicspectacle/2013/06/20/my-mother-was-the-mistress-of-the-owner-of-cliftons-cafeteria

Best of luck–cannot wait to patronize the new iteration of Clifton’s. This story was great. It reminded me of another cafeteria/city institution, Sholl’s in Washington DC. Sholl’s was not an imaginative place to eat, but its owners were as philanthropically- and community-minded as the Clintons (minus car bombs!).

Thanks for the link, Ray. Wow – what a story! :)

loved this place as a kid…both of them!

went to the one in West Covina and the one downtown (late ’60s) – it is so true – the whole staff was warm, kind and caring despite the huge crowds they catered to – they always gave you a personal welcome – here’s hoping the new Cliftons will also be open at lunchtime and not just as a nightclub?

My grandmother took mej there on the RedCar from Pasadena. I don’t know the year, but it was

During the war & there was no sugar on the table. I think I remember a water fall inside. I was

About 5 yrs. old.

Great article, but nothing about the role of Mrs. Clinton in the kitchen — her recipes, her involement in the kitchen even as she aged.

Great to see these articles….so good to know that there are always good, helpful people in all of our generations,,,,Thanks

I can’t wait till you open so we can go back. I have been going here since I was a little girl, my grandmother and I had lunch her once a week I can’t wait to visit when it opens. I introduced my husband to this place when we got together and he loves the place as well. My family will be there when you open.

I have a rose cut glass window that came out of the Clifton’s restaurant in West Covina. I’m am trying to get any information on it as possible. ie: circa, designer ect. Any help would be appreciated. photo is avail to email if needed.

Thank you

Big Basin Redwoods is the first California state park, not a national park. And, while the Clinton family might have some solid civil rights credentials, the SF Clinton’s Cafe mentioned was the site of a gay revolt of sorts, 3 years before the more famous Stonewall Riot in 1969, now considered the touchstone of the gay rights movement.

When IS this place going to reopen? Has the scaffolding come down from the facade—is it, at least, fully restored? Can’t wait!

I’m looking for the name of a cafeteria that was in Santa Monica, CA around 1980-85. It was located on Ocean Avenue, around California street, overlooking the Palisades and the beach. I think it was a French firm (since I saw a duplicate once in Paris). It had patio dining.

Any thoughts on the name?

A couple of years before he died, my father-in-law wanted all of us to go for a meal at Clifton’s; despite having grown up in Pasadena, he’d never been there because his mother was a snob who believed that poor people were simply shiftless and lazy, and was outraged that this place was handing out free meals to “bums”! But his daughter and I had tried it and loved it, so we loaded Mom and Dad into the car one Saturday and went down there.

If the quality of the food had degenerated as the article suggests, we found no proof of that. My plate of braised short ribs with real mashed (NOT whipped) potatoes and green beans was as good as I’d ever eaten, and everyone else was pleased as well. Nobody was happier than Dad, though – he always paid for our communal meals, but was still (let’s say) careful with his money, and the smile on his face when he got past the cash register was wonderful to behold!

I was thrilled to hear that Clifton’s Brookdale will be reopened. Many years back I’d heard that it was closed and was so disappointed that I would never be able to go back there, or to introduce my children and grandchildren to this wonderful cafeteria. Apparently I was misinformed, and it was actually closed much more recently than I thought. Is there any current info on an opening date? I can’t wait!

I’m wondering if a “collection of recipes over the decades” cookbook might become available? I would stand in line all night long to purchase one!! Clifton’s Cafeteria is a huge wonderful childhood memory for me (1950s) as it meant my mom, grandma and sister were downtown shopping. The really best part was the star on my receipt, which allowed me to pick a toy from the Treasure Chest. Please consider publishing a collection of recipes — I would so love to have one. Thanks

While at UCLA in the very late 1950s, I worked in a Beverly Hills art store (Duncan Vail) with a young guy named Bill Tangeman whose father was the organist at the Brookdale. While he played, the caged canaries sang! I hope the canaries will be back.

As a child, we’d go to a Clifton’s after the “Young People’s Concerts” at the old Philharmonic Hall across the street from the north side of Pershing Square. I particularly loved the “Pacific” one with the thatched roof cabanas and rain and thunderstorms every twenty minutes!

And what’s not to like about a fountain that spouts limeade? I also remember mint water (?) coming out of a grotto wall at one of them.

It was the 1940s and I was very young!

I am looking for the old Mac n Cheese receipe. That one was a family favorite. Is there a site with receipes? You stated you had all the recipes. Any chance you would share that with me via email?

Are there pictures of the Garden of Gesemenie.I remember being there as a child

Would love that wonderful enchilada recipe. I remember eating there when I was 16, working at Kay Jewelers. There was a May Company as well at Eastland Mall. What great memories. I would absolutely love to make those. I am now 65. It’s on my bucket list.

Thanks a Million, if you can send it

I would love the enchilada recipe. Have they ever had a book made of the old recipes? I am looking for a recipe from the 40-50’s since most recipes of todays time are basically fast food type or in the microwave. I am 55 but like to cook the old fashion way