At the World Museum in Tulsa, Oklahoma, the three shrunken heads from the Jivaro tribes in Peru and Ecuador—with their shriveled, leathery skin, and sometimes threads strewn from their mouths—were the showstoppers. While the museum held life-size sculptures of headhunters, Thai orchestra instruments, several paintings by Gustave Doré, giant elephant tusks, and artifacts from ancient Chinese dynasties, it was the shrunken-head display that drew crowds. Adults and schoolchildren would stop and gawk.

“Not many Okies in 1970 got to travel to the ends of the earth to see art produced by people in other cultures.”

But the World Museum, which liquidated its assets in 1981, wasn’t just another one of Tulsa’s quirky roadside attractions; this collection of art and artifacts was said to rival the holdings of some of the Smithsonian Institute museums.

Unlike those collections, every item it contained was gathered by one “missionary evangelist” couple, Tommy Lee “T.L.” Osborn and his wife, Daisy, who traveled from country to country from the 1940s to the 1990s, performing healings and establishing churches.

The closing of the World Museum symbolized the end of an idea borne out of Victorian curiosity: Missionaries as anthropologists. Since 19th-century missionaries were already making difficult journeys abroad and connecting with indigenous peoples, they made obvious candidates to help Western institutions document the cultures of the world. Indeed, missionaries have contributed important artifacts to natural history museums all over the United States.

Top: The late T.L. Osborn prays behind a Vishnu figure in India in 2011. (Via the T.L. Osborn Facebook page) Above: The home of the World Museum in Tulsa, which was used by the Victory Bible Institute after the museum closed, was demolished in 2009. (Photo by Rex Brown, via OklahomaModern.us)

For 200 years, typical North American “resident missionaries” have tended to stay in one country for the duration of their career, which gives them a unique opportunity to immerse themselves in one particular foreign culture. In Victorian times, the artifacts they collected during such stays were often donated to educational institutions like natural history museums and universities. But a globe-spanning missionary collection is rare: Only one such U.S. collection, which dates back more than 100 years, still lives in storage at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. And it’s unlikely the U.S. will ever see a large-scale, high-profile global collection celebrating its evangelical roots, like the one at The World Museum, again.

Today, such an exhibition would be controversial, as the repercussions of colonialism, cultural appropriation, and economic globalization are being hotly debated. Even international charity, a large piece of Christian missions—from building schools and digging irrigation systems to providing medical and legal aid—has been called into question as a heavy-handed and unnecessary intervention into the lives of native peoples.

Bishop LaDonna Osborn, who continues to run her parents’ ministry as vice president and CEO of Osborn Ministries International in Tulsa, Oklahoma, says that T.L. and Daisy were never out to Westernize other countries or pave the way for American commercial interests. “That was an old-fashioned dynamic,” she says, “from the 18th century, when colonial rule was alive and the missionary movement began in Europe. It’s easy to imagine the mentality under colonialism, that ‘We have to take these primitive people and teach them our ways, so they can be more civilized.’ That is not the world we live in today.”

The rotunda of the World Museum in Tulsa was a relic of the 1960s. Pictured before it was demolished in 2009, click to enlarge. (Photo by Rex Brown, via OklahomaModern.us)

In the 19th century, Americans and Europeans still largely supported the notion that people in developing countries, as well as Native Americans, were “savages” who needed Westerners to come in and teach them the right way to live—and in doing so, of course, opened the door for their own businesses to exploit native workers and material resources. In February 1899, American magazine McCall’s published English writer Rudyard Kipling’s poem, “The White Man’s Burden.”

Take up the White Man’s burden—

Send forth the best ye breed—

Go send your sons to exile

To serve your captives’ need

To wait in heavy harness

On fluttered folk and wild—

Your new-caught, sullen peoples,

Half devil and half child

According to Barbara Lawson, curator of world cultures at the Redpath Museum at McGill University in Montreal, white European commercial interests hit faraway shores first between the 15th and 19th centuries depending on the regions involved. “In the period of first contacts, these visitors were trading things, whaling, collecting furs, or looking for sandalwood or other types of rare materials,” she says.

A piece of decorated barkcloth from the South Seas archipelago New Hebrides, also known as Vanuatu, that 1800s Canadian missionaries H.A. and Christina Robertson donated to the Redpath Museum in Montreal. Click to enlarge. (Courtesy of Barbara Lawson, Redpath Museum)

But the sailors were rowdy bunches, who tended to rub the native peoples the wrong way. “The traders, usually ships full of young men, had pretty bad reputations for their interactions with local populations,” Lawson says. “They were often anxious to interact with the people there, and particularly, the women. I think perhaps missionaries felt the need to counteract the negative, and what they perceived as the un-Christian behavior of these traders.”

“They used curiosity to lure the visitor in, but they wanted people to witness the transformation Christianity had on these cultures.”

The first Protestant missionaries from North America left for Burma (now Myanmar) in 1812. Missionaries of the Victorian era, like H.A. and Christina Robertson, whom Lawson wrote about in her book, “Collected Curios: Missionary Tales From the South Seas,” often came from impoverished, rustic existences themselves. Usually, only a handful of people—a man, his wife, and maybe their children—would travel to a mission field, where they would be incredibly dependent on the locals for food, water, and shelter. While the missionaries would naturally have to adapt to many local ways, Lawson says, ultimately, their evangelizing led to colonialism.

“You teach people about God, and then you help them to organize their time in a way that is more similar to the way that the Western world does,” Lawson says. “Then, you also encourage those people to have an interest in money. This was all a part of Victorian ideals of progress and economic development.”

A hand fan made of woven palm leaves, another piece the Robertsons brought home from Vanuatu. (Courtesy of Barbara Lawson, Redpath Museum)

Erin Hasinoff, a fellow in the Division of Anthropology at American Museum of Natural History (AMNH), agrees that in the Victorian era Westerners assumed that non-Western cultures were inferior and their people were in need of reform to become productive Christian workers.

“Even now, the public is mad about them; I call it ‘shrunken-head fever,’ because they can’t get enough.”

“In this era, societies were ranked, from the lowest, which would be ‘heathenism,’ to the highest, which would be American or European culture, and it was then believed that one could ascend this ladder of humanity,” Hasinoff says. “To help them do so, churches could offer medicine or education and encourage the people to come out of the ‘heathen’ darkness into the light that was capitalism and Christianity. And these people would then become better laborers, for example, because they would have disciplined hands and hearts and heads and minds. This was part of the Protestant work ethic.”

To their credit, Victorians—the first real Western middle-class born out of the Industrial Revolution—were intensely curious about the world. In America, East Coast tourists took trains to Southwest America to experience Native American culture, dauntless young men joined the Navy, and wealthier adventurers boarded ships to Africa for hunting expeditions and safaris. Scientists like Carl Akeley, the “father of taxidermy,” and Charles Darwin, who developed the theory of evolution, traveled the globe to document plant and animals species. Newly founded natural history museums and zoos were wildly popular.

One of the shrunken heads, which may or may not be fake, at the Redpath Museum in Montreal. (Via MontrealInPictures.com)

Victorian tourists brought home physical objects and plant specimens as souvenirs of their trips, because for most of the 19th century photography was a slow, cumbersome process involving heavy equipment. It wasn’t uncommon to have a “cabinet of curiosities” in one’s home. Jivaro shrunken heads were such popular souvenirs, Peruvians and Ecuadorians started making fakes to sell as curios.

In fact, these creepy objects are still a hit at the Redpath Museum, which has three in its collections, possibly made from monkeys. “Even now, the public is mad about them; I call it ‘shrunken-head fever,’ because they just can’t get enough of them,” says Lawson. “In the 19th century, they were a popular item because they represented something so exotic and mind-boggling and such a conversation piece that everybody wanted to have one. So local populations in Ecuador and Peru met the demand, and many of these were made for sale. Originally, they were taken as trophies in battle and for spiritual reasons, to gain spiritual power over the enemy. But when it came to making these for sale, they might have been taken from a person who may have just died from illness or old age. Locals also became adept at making monkey skulls look like human ones.

“This happens in terms of all types of objects,” Lawson continues. “Whether it’s weapons or cannibal forks or anything that rings of the exotic, these may have been objects that were in use at one time, but because they are so popular for Victorian tourists who love anything that’s macabre, oftentimes locals started producing them and making money.”

A comb from 1800s Vanuatu brought to Canada by the Robertsons. (Courtesy of Barbara Lawson, Redpath Museum)

Like the tourists, missionaries brought back items that seemed to capture the essence of the region they worked in. When they went on furlough, spending a year in America after five to 10 years in the mission field, the missionaries would tour churches to speak about the work. They also brought magic lantern slides and objects to convince congregations that these people were desperately in need of redemption. Of course, these curios, shown at churches and interdenominational meetings, sparked intrigue among the faithful.

“Obviously, missionaries wanted people to adopt Christian ways, which sometimes were opposite to local belief systems,” Lawson says. “If the people had objects that represented their own gods or their own spiritual beliefs, many times missionaries would like to remove these items from local practice and introduce their own objects such as bibles, prayer books, and hymnals in the native language. So there’s not only a taking away, but there’s this process where missionaries are trying to introduce new cultural practices.”

On rare occasions, missionaries would ask locals to destroy their heathen objects, but more often, the locals simply handed them over to the missionaries, who brought them back to North America when they were on a yearlong furlough. “Oftentimes in their home church, there would be a Sunday-school re-enactment where half of the children would play missionaries and the other half would be islanders, who would wear grass skirts or typical native dress,” Lawson says. “The children would put on these plays that would be essentially missionaries versus ‘heathens.’”

When they retired, the missionaries would bring home the items they’d accrued from living in another country for decades. The Canadian missionaries Lawson studied, H.A. Robertson and his wife, Christina, arrived in the Melanesian archipelago Vanuatu (then called New Hebrides) around 1870. Their collection, which was donated to the Redpath Museum starting in 1883, contains hand fans made of woven palm leaves, tapa-cloth floor mats, bowls made from coconut shells, and accessories made of clamshell.

“The majority of these objects were acquired by exchanging metal tools, cloth, or other things that were part of Western society,” Lawson says. “Another reason that missionaries brought objects home was to show the technical skills, like weaving, of the local populations and to encourage commerce or manufacturing.”

In the 1900s, missionaries hosted tea parties to showcase these items, and such events were becoming trendy. But they weren’t nearly as popular or impressive as the large international expositions, also known as World’s Fairs, which started in London in 1852 and were held regularly throughout Europe and America. Around 1899, Christian leaders started to consider how a World’s Fair-type event, with interactive booths meant to re-create life in another country, could promote missionary work.

The organizers of the 1900 Ecumenical Conference on Foreign Missions in New York City figured that a large exhibition of global curios would bring in money and support for their work.

To create this exhibition, “basically, every known American missionary society received a circular in 1899 with a request for objects, whether they were in Hawaii or Burma or Africa,” says AMNH’s Erin Hasinoff, the author of “Faith in Objects: American Missionary Expositions in the Early Twentieth Century.” “The conference received a whole range of things representing everyday life, such as articles of clothing, objects of personal ornamentation, and wares that one would use in the home.

A souvenir postcard show two women wearing native dress in the Burma Court section of 1911’s missionary exposition “The World in Boston.”

“You see objects that were contributed by a teacher, and her students’ names are written on the object, with their standard or grade level,” continues Hasinoff, who’s handled the collection personally. “To me, that’s so extraordinary because you get a very faint trace of the individual who took it upon themselves, however old they were, to go home and say, ‘Hey, there’s a missionary exhibition in America. Let’s send some objects.’ There are also wonderful slate teaching books, used for teaching Pali or basic Buddhist texts, and the missionary likely approached the local pongyi, or monk, whose name appears on it. They show the relational ties between the missionaries and their communities.”

The 1900 conference, a major event at Carnegie Hall, drew politicians like former President Benjamin Harrison, President William McKinley, and New York Governor Theodore Roosevelt, as well as tycoons like John Pierpoint Morgan and John D. Rockefeller. As speakers detailed the successes and obstacles of foreign missions, a side attraction across the street was the Missionary Exhibit, which took up three stories of the parish house at the Church of Zion and St. Timothy.

Franz Boas in 1915. (Via WikiCommons)

The displays in this exposition featured photographs, models, maps, and charts, as well as objects or “missionary curios” from the respective countries. There, a visitor might see edict boards from Japan, lotus shoes for bound feet from China, a book of pressed flowers from Bulgaria, or fetish figurines from Congo. Some exhibitors put on costumes and played characters from various cultures, sometimes even performing a native skill, such as making lace.

“There were also objects that showed the effects of missionization, like Bibles in the native language, and tracks or leaflets that the missionaries distributed,” Hasinoff says. “The exhibition was designed to document the effect the missionaries had, the social changes they brought, and what missionization could accomplish for these so-called ‘heathen’ societies.”

The American Museum of Natural History’s assistant curator, Franz Boas, who’s been called “the father of American anthropology,” took an interest in this Missionary Exhibit. A secular Jew and an outspoken cultural relativist, Boas didn’t see the display as a way to promote Christian missions. He saw it as an opportunity to expand the museum’s anthropological collections. After the conference, the collection, which contained artifacts from nearly every Protestant mission field—including North America, Latin America, Oceania, Korea, Laos, Siam, Malaysia, India, Turkey, Persia, Syria, Egypt, and Madagascar—was packed up and delivered to the museum.

This souvenir postcard depicts a Buddhist temple, temple lanterns, and torii at the Japan Scene in “The World in Boston.”

“Boas actually went to the conference, which was surprising,” Hasinoff says. “He also met with missionaries to convince them to collect on the museum’s behalf and in a way that would be systematic. Boas would be able to correspond with the missionaries and say, ‘Let’s direct your attention this way’ or give particular recommendations as to what to collect. That way, their collections wouldn’t be ad hoc or random, which the Missionary Exhibit was, and which missionary collecting generally tends to be.”

Encouraging missionaries to think like scientists, Boas asked them to gather objects like botanists, biologists, or archaeologists would, using a more methodical approach to fill in all the gaps in the Missionary Exhibit. But for all Boas’ efforts, the collection never developed to match his ambition for it, and he left the museum in 1905.

In 1907, a group called the Young People’s Missionary Movement, which had a vision of a true missionary world’s fair, took responsibility for working with the American Museum of Natural History to manage the missionary collection. The group’s dream was to put on a series of huge World’s Fair-like events, all about missions. (They were beat to the punch by English missionary groups who put on “The Orient” in London in 1908 and “Africa and the East” in Liverpool in 1909.)

A souvenir pinback advertises “The World in Boston,” held at Boston’s Mechanics Building from April 22 to May 20, 1911.

Eventually, the American missionaries convinced a group of wealthy New York backers to incorporate as the Missionary Exposition Company, and this new firm helped them secure the necessary costumes, props, and scenery. AMNH anthropology curator Clark Wissler even lent objects from the museum’s other collections to their fair, “The World in Boston,” which took place from April 22 to May 20, 1911.

“In this era, societies were ranked, from the lowest, which was ‘heathenism,’ to the highest, which was American or European culture.”

At the block-sized Mechanics Building exhibition hall in Boston, the 400,000 visitors could ride a rickshaw and enjoy a Japanese ceremonial cup of tea, experience the colorful regalia and joyful singing of a wedding in India, and take in a lecture on how the evil known as opium was affecting China. They toured structures like replica temples, pagodas, African huts, and Bedouin tents, as volunteers filled the roles of artisans, street hustlers, fortune-tellers, and Buddhist monks. The “domestic” scenes depicted Native Americans, what were billed as “our foreigners at home,” and black American slaves in chains.

“A lot of people attended World’s Fairs for pure pleasure and walked along the midway to get a kick out of seeing exotic peoples on display.” Hasinoff says. “‘The World in Boston’s’ organizers wanted to use curiosity as a way to lure the visitor in, but not allow it be the entire outcome of one’s experience. They really didn’t want people to lose sight of the meaning, which was to witness the transformation Christianity had on these cultures. Presumably, one could sign up to become a missionary at ‘The World.’”

“The World in Boston’s” American Indian Scene, captured on a postcard, was described by the exposition as “our foreigners at home.”

“The World” was so popular in Boston, that, naturally, the organizers, now renamed the Missionary Education Movement, took it on the road. “The World” traveled to Providence, Rhode Island; Baltimore, Maryland; Cleveland, Ohio; and Chicago; and also inspired many imitators around the country. But the outbreak of World War I put a halt to the fun. One of the outcomes of the war was to make Americans and Europeans more aware of the global frustration with Western paternalism, which prompted Catholic and Protestant organizations to rethink their approach to missions.

“You teach people about God, and then you encourage them to have an interest in money.”

Thus, missionary exhibitions faded into the past, as Protestants shifted their focus toward the concept of “world fellowship” and set about recruiting and training indigenous people to evangelize to their own. The authentic Missionary Exhibit artifacts were returned to storage at the American Museum of Natural History, while the Missionary Exposition Company held on to its American-made props and costumes, for fear the items would see secular use.

“Over time, you see a shift toward world friendship and trying to understand and respect local cultural practices,” Hasinoff says. “In the 1910s, terms like ‘idol’ definitely came up. By the ’50s and ’60s, you wouldn’t find ‘idols’ or ‘fetishes’ being circulated in Sunday school classrooms. By then, the idea was to incorporate the local communities into a larger Christian partnership that recognized certain indigenous ways. So missionaries might bring back handwork or beadwork to show the native skills instead.

The postcard for this “World in Boston” display only describes it as “Native House, Africa Scene,” with no indication as to the country.

“At that point,” Hasinoff continues, “a lot of traditional cultural practices were re-enlivened. People played traditional music, and they wore traditional clothing in the mission churches. Now, a lot of the missionaries—and this has been true for a long time in places like Burma—are indigenous people themselves. The foreign missionaries came in and built the seeds of the church, cooperating with the locals and developing an indigenous clergy.”

It would be decades before the United States would see anything quite on the scale of the World, and it was this mid-century idea of seeding churches around the globe that brought another worldwide missionary collection into being. In 1938, Tommy Lee “T.L.” Osborn, a poor farmer’s son, left his hometown of Pocasset, Oklahoma, at age 15 to evangelize with traveling preacher E.M. Dillard. While they were in California, Osborn met a farmer’s daughter, Daisy Washburn, whom he married in 1942.

Daisy and T.L. Osborn pose with crutches, canes, and prosthetics abandoned by people who had been healed. (Via the T.L. Osborn Facebook page)

The young couple, 18 and 17 respectively, struck out on an American mission of their own, returning to rural Oklahoma before traveling up the West Coast. After establishing a church near Portland, Oregon, the Osborns were told that India was full of pagans who were desperately in need of Christian salvation; the pair sold everything they owned and headed to India in 1945.

“In India, they were confronted with religious people, Hindus and Muslims who were devout in their faith,” says their daughter, Bishop LaDonna Osborn. “They just didn’t believe the Bible was God’s word, and so my mother and father were helpless to try to convince people of other faiths.”

The couple gave up on Christianizing India within a year and made their way back to Oregon. In 1949, they joined a 13-week mission to Jamaica, with their two young children, LaDonna and her big brother Tommy Lee junior, in tow. There, the family claims to have performed healings on hundreds of people with conditions such as blindness, deafness, cancer, and deformities. Then, the grateful locals presented them with gifts, treasured art, and artifacts.

These ancient Asian bronze statues were a part of the World Museum’s collection. (Via This Land Press)

So it went, as the Osborns built their international ministry: They’d travel to a mission field for a few short months to help establish indigenous-led Christian churches. While there, they’d hire translators, perform miracles at huge events that drew hundreds of thousands of people, and be showered with gifts. The couple evangelized to 40 countries between 1950 and 1964.

“We traveled to nation after nation after nation with the Gospel, working with local pastors and the ministry,” LaDonna says. “In fact, my mother and father pioneered many of the methods that have become commonplace in evangelistic work today, for example, the mass crusade, that whole concept of going out into an open field and inviting everyone to come. My mother and father were the first to even do such a thing.”

T.L., who passed away earlier this year, saw the gifts as collateral, a way to finance Osborn Ministries International—which they moved to Tulsa, Oklahoma, in the early ’60s—when times got tough.

The Peruvian shrunken head on the left dates from 1925-1950, and was probably made-to-order. The other two in the World Museum are said to be Jivaro tribe trophies, circa 1900-1925. (From the Christie’s catalog, courtesy of LaDonna Osborn)

LaDonna says, “I can remember my father telling me when I was just a young adult, ‘After we’re dead and gone, and you’re low on money and you need to make payroll, you can just sell a piece of art and that’ll help you. Don’t borrow money. You’ll just have this art, and that’ll endow the ministry.’ So that was always in the back of our heads.”

But, according to This Land Press, the ministry was well-funded through donations, which its foundation solicited through its magazine, Faith Digest, thought to bring in as much as $6 to $8 million a year.

“The ministry took my mother and father, simple people, to the ends of the earth,” LaDonna says. “The World Museum began with the gifts that people would give to them—sometimes simple, sometimes amazing, sometimes small, sometimes large. My father and mother just seemed to be natural collectors, so they valued all of the gifts and would bring them home and store them.”

A 1923 Rolls Royce “Silver Ghost” Tilbury cabriolet limousine that T.L. Osborn and his family restored. (Courtesy of LaDonna Osborn)

And T.L. was also a bit of a picker. T.L. would find rusty old cars, and his brother-in-law would help him restore them—which is how a 1920s Rolls Royce ended up in the World Museum. “My mother and father had a classic car collection,” LaDonna says. ”My father would find these vehicles as just junkers. I don’t remember that he paid more than $300 for any of them. But my mother had a brother who was gifted in car restoration, so that’s what my family did as their hobby. They would restore these old cars with their own money, and it would take years and years. When my children were little, we would go on rides around the country in one of these old cars.”

When in Paris, T.L. picked up cracked or damaged marble sculptures, rejected by prestigious art museums, for low prices. “My father just had an eye for art,” LaDonna says. “And he had a nose for bargains. For example, in a field near the Louvre Museum in Paris, he found some marble sculptures that were not being restored or protected at all. Apparently, the collectors there didn’t want them, so he was able to get them for a couple of hundred dollars, just a fraction of what they were worth. He just happened to come on things at a right time.”

An 1876 marble sculpture by Louis-Ernest Barris, titled “Le Serment de Spartacus” was one of the French artworks in the museum. (Courtesy of LaDonna Osborn)

In 1963, the 42-year-old missionary opened the a gallery of artifacts in the rotunda of his new temple near I-44 in Tulsa, in a futuristic Mid-Century Modern building that looked a bit like a clamshell. A large, circular vinyl carpet in the center read, “Go ye into all the world and preach the Gospel to every creature. Our supreme task is world evangelism.” There, the Osborns showcased the items they’d collected or restored over more than a decade of missionizing.

Within 10 years, the collection had gotten large enough—5,000 artifacts from 100 countries—that the Osborns added a second floor. Oklahoma governor David Hall gave a speech at the 1972 grand reopening of the 50,000-square-foot attraction, which had a new name: the World Museum Art Center.

“It just began to explode, as people started giving entire collections to my parents,” LaDonna says. “Two galleries alone were full of Oriental art that was given by a man who was in the military in Korea. He lived there 40 years and collected all those years. He gave everything to the World Museum just because of the reputation of the ministry and the museum. We had everything from primitive art, things that were 1,000-1,500 years old, maybe even older, collections from the early dynasties of China, an entire gallery of those wonderful marbles, and Old Master paintings, like the Dorés.”

The large vinyl rug at The World Museum read, “Go ye into all the world and preach the Gospel to every creature. Our supreme task is world evangelism.” Pictured before demolition. (Photo by Rex Brown, via OklahomaModern.us)

To bring in a New Guinean 57-foot-long war canoe and a 37-foot banana boat carved from a single tree, the Osborns had to get creative. “The canoe had been preserved because my parents found it in mud,” LaDonna says. “We crated it back to the States. We had to actually knock out some of the blocks from the back of our building. Then, we brought in a crane.”

The museum also contained the three shrunken heads, an elephant’s foot, cow skulls, talismans, swords, gongs, pagan deities, monster statues carved from trees, mechanical villages from the Black Forest, music boxes, and naturally, the Rolls Royce. In the 1970s, more than 6,000 visitors a month toured the facility, while T.L. turned down increasing requests for interviews.

Two more items from the World Museum from 20th century Papua New Guinea, Indonesia: A 4-foot-4-inch Sepik River basketry gable mask, and a 3-foot-7-inch polychrome Yuat ancestor sculpture of a mother nursing a boy. (From the Christie’s auction catalog, courtesy of LaDonna Osborn)

“We put captions right on each object: where we got this, what tribe it was from, and maybe what they called this god and how they would worship that god,” LaDonna says. “We didn’t do a preaching thing about how bad they were or how rough they were. One thing that was really consistent throughout the museum in our captions was drawing attention to the creativity of human beings.

“I’m an evangelist. I’m not going to give the rest of my life to art. Let’s put it in the hands of collectors.”

“Think about Oklahoma in 1970: Not many Okies got to travel to the ends of the earth to see what we would call art or the things that are produced by people in those cultures,” she continues. “Imagine the potential for learning when you can walk through the symbolic, sacred, and economic objects from more than a hundred nations. All the nearby public schools took their children on field trips to the museum.”

By the late 1970s, the museum had swollen into a full-fledged institution, with a curator, guards, and tour guide, which the public associated less and less with the ministry that created it. When the Oklahoma Tourism Board came calling, they reminded the Osborns that they had a priceless collection housed at their museum, which the family would be responsible for caring for as long as they lived. The Osborns also learned that their facility, which was not temperature- or moisture-controlled, would not protect the objects long-term.

The 1877 painting “Ecce Homo (Behold the Man)” and the 1883 painting “The Valley of Tears” were two of Gustave Doré pieces hanging in the World Museum. (Courtesy of LaDonna Osborn)

“My folks and I were taken to lunch by someone high in the tourism board,” LaDonna says. “This woman was complimenting the museum, saying it was just the finest collection of art west of the Mississippi. She said, ‘You have given half of your lives, collecting these items. Now you must spend the rest of your life protecting them.’ And I knew in my heart that was the end of the museum.

“We finished our lunch, came back, had a board meeting, and my father said, ‘I am not going to give the rest of my life to taking care of pieces of art. I’m an evangelist. My priority is to help people know Jesus, and so the art is going to go. It is precious, indeed. Let’s put it in the hands of art collectors who will take care of it, who will cherish it and let it endure for coming generations.’”

That’s when the family brought in Christie’s auction house to help liquidate their collection, which was put on auction and sale in September 1981. The family held on to some Dorés, a few pieces of Asian art, and a handful of sculptures for their home. On auction, a Doré painting, bronze and marble sculptures, and Louis XIV clock each went for five figures, according to This Land Press. “We had our major auction here in Tulsa, but the Old Masters paintings were sent to New York where they could be exposed to the high-dollar art world,” LaDonna says.

T.L. Osborn’s wife, Daisy, was integral in the operation of Osborn Ministries International. She also authored five books. (Via Osborn.org)

When T.L. Osborn bought some of these pieces for basement-bargain prices in the Mid-Century Modern era, people rejected anything seen as old or stuffy, like Baroque and Romantic art, in favor of new Space Age plastics. But by the time of the Christie’s auction in the 1980s, the tides had turned. “France had passed new laws that would disallow any of their antiquities from being purchased and shipped out of the country,” LaDonna says. “A lot of collectors from other countries, especially Europe, came to our auction and took back their nation’s treasures.”

In total, the collection brought in $3 million for the ministry, and The World Museum was no more. “When it came time for the auction, we were probably very ignorant and ill-prepared to handle it properly because from the entire museum of art, all these wonderful things we collected over these many decades, we’d received just $3 million for everything,” says LaDonna. “And of course, that money was reinvested in evangelism and was gone within about three years. Probably, if someone had been smart and patient, that art collection could’ve realized a whole lot more money.”

LaDonna Osborn keeps this eight-fold Chinese hardwood screen in her office at Osborn Ministries International. The porcelain panels are enameled with heroic exploits from Chinese legend and romance. (Courtesy of LaDonna Osborn)

In 1994, the Osborns donated the building to the Victory Christian Center, who used it for the Victory Bible Institute, while still sharing some of the space with Osborn Ministries International. T.L.’s wife, Daisy, passed away in 1995, and four years ago, the Space Age complex was demolished to make way for a freeway expansion. Today, Osborn Ministries continues under LaDonna’s direction, from another location in Tulsa.

“We go to people and we bring a message of God’s love to people, accepting people of all religions. We endeavor to help them understand that God loves them and comes to them through Jesus Christ, but we’re not tied up in arguing religious points,” says LaDonna, revealing the main motif of the World Museum. “I’m sitting right here in this office, looking at an Asian screen that is inlaid with mother of pearl and all different colors of bone to produce the most delicate, beautiful, lifelike scene that you can imagine. They’re so beautiful. And most of the people who do these things, they don’t have a God consciousness. They’re just people who have a creative talent, but we believe it’s because God created them. You never saw a dog carve anything or a monkey do a sculpture. No. God has instilled in people part of his own creator nature.”

T.L. Osborn prays outside a temple on a mission trip to India in 2011. (Via the T.L. Osborn Facebook page)

(Recommended reading: “The Oddities of Evangelism,” by Holly Wall at This Land Press; “We Needed Miracles,” by Bill Sherman at Tulsa World; “The World Museum,” by Rex Brown at Oklahoma Modern; Erin Hasinoff’s book “Faith in Objects: American Missionary Expositions in the Early Twentieth Century”; Barbara Lawson’s book, “Collected Curios: Missionary Tales From the South Seas.” )

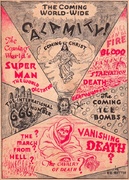

Hellfire and Damnation in Your Back Pocket

Hellfire and Damnation in Your Back Pocket

Why the 'Native' Fashion Trend Is Pissing Off Real Native Americans

Why the 'Native' Fashion Trend Is Pissing Off Real Native Americans Hellfire and Damnation in Your Back Pocket

Hellfire and Damnation in Your Back Pocket How Collecting Opium Antiques Turned Me Into an Opium Addict

How Collecting Opium Antiques Turned Me Into an Opium Addict Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

I can’t recall how many times I drove by this museum in Tulsa on the way to a shopping mall! It is probably the only museum in Tulsa I haven’t been in and now it is too late. Great story Lisa.

I visited the museum as a class trip in HS. Very cool place. Thanks for the story, Lisa!

I remember as a kid going through the museum and being fascinated with those shrunken heads. My uncle TL and Daisey lived above the museum. It wasn’t a big place but it was beautiful. My grandmother Verna was TLs sister she wrote a small book before her death about growing up in her family. The Osborn family produced many preachers and word of God teachers. Proud to be a part of this family.

I am trying to find information about an artist that was with missioaries in Africa, sculpting religous figurines of female saints in 1949 made of ivory. As far as I can make out, his name was Mamceaus the second.

My husband and I recently purchased a 1930 Lincoln which we learned belonged to the TL Osborn family. If you could tell me more about that car, we would love to hear from you. Thank you in advance.