Duane Scott Cerny, author of “Selling Dead People’s Things.”

As a child, Duane Scott Cerny didn’t exactly dream of growing up to become one of Chicago’s premier antiques dealers, but his early entrepreneurial instincts should have been a clue that one day he would. His eyes were opened to the world of resale on an unlikely day, November 22, 1963, at the tender age of 4, when the assassination of President Kennedy interrupted Cerny’s lunchtime ritual of watching “Bozo’s Circus” on TV. What, young Cerny wondered, could possibly be more important than Bozo? The answer, of course, was a sensational murder.

“I think when you can’t have people over, you’re a hoarder.”

In his new memoir, “Selling Dead People’s Things,” Cerny explains the lesson he learned on that dark day, beyond how the violent death of a president could cancel his beloved Bozo. “I soon discovered that great disasters in history often generate near-instantaneous collectibles,” he writes. In this case, Cerny noticed the enthusiasm his father’s friends showed for collecting newspapers announcing JFK’s death. “Most coveted,” Cerny writes, “were the early editions from numerous newspapers across the country that first stated Kennedy had been wounded or shot, not killed.”

Detailed observations like these fill “Selling Dead People’s Things.” As its title suggests, the book introduces readers to lots of “things,” such as all those 1963 newspapers. But at its core, “Selling Dead People’s Things” is mostly about the people—be they dead or alive—who make the world of antiques, vintage, and collectibles so memorable. Indeed, Cerny seems to say, things may come and go, but it’s the memories of the people you meet in the pursuit of things that really stay with you.

The assassination of President Kennedy and his father’s job at the company that printed “Playboy” influenced how author and antiques dealer Duane Scott Cerny (top) viewed objects and collectibles.

Cerny began pursuing things before he’d even turned 10. In “Selling Dead People’s Things,” Cerny introduces readers to himself as an 8-year-old playground entrepreneur, who’d convince his peers to let him trade their neglected Tonkas and “too-often-buried” G.I. Joes for something better, with Cerny taking a small commission, of course. “Basically,” he writes, “I’d started a resale store for toys—not a particularly ingenious idea, but it was surprisingly successful.”

By high school, in the mid-1970s, Cerny had graduated to more sophisticated merchandise, dealing in high-quality 5×7 and 8×10 prints of “Playboy” playmates that his father had brought home from work—Cerny’s dad worked for Superior Graphics, which printed Hugh Hefner’s magazine. Apparently, Cerny’s father thought a folder full of pictures of naked ladies might startle the gay out of his teenage son, whose bedroom in those days featured white plastic furniture, a white fake-fur bedspread with matching drapes, and a record collection that leaned heavily to musicals (“By all appearances, I am gayer than Quentin Crisp’s cravat.”). Cerny’s mother, however, nixed the idea and made his father throw the photographs in the trash, which is where Cerny retrieved them so he could peddle the soft-core smut to his horny heterosexual friends. Cerny remembers this little enterprise netting him about $500.

Cerny behind the counter at Wrigleyville Antique Mall, circa 1990s.

Somewhere in the early 1980s, when Cerny was making ends meet as a freelance paralegal—his writing-related side hustles included a resumé-writing service—he took his first tentative steps into the world of actual antiques. Initially a customer of the sprawling Chicago Antiques Mall, he soon found himself in charge of the mall’s merchandising before partnering with Jeff Nelson to sell antiques in the mall’s basement. By 1990, Cerny, Nelson, and a pair of short-lived partners had opened an antiques mall of their own. Named for its surrounding baseball-park neighborhood, the Wrigleyville Antique Mall lasted eight years before Cerny and Nelson opened the Broadway Antique Market, where Cerny still buys and sells everything from kitschy 1960s school lunch boxes to coveted pieces of Mid-Century Modern furniture.

“Selling Dead People’s Things” walks the reader through this history anecdotally, which means the prose is a good deal more engaging than the preceding paragraph. Along the way, we meet Tom Neniskis, one of Cerny’s most important mentors, who died of AIDS back when people still called the disease the “gay cancer,” as well as Hy Roth, the late, self-described “most famous unknown person in Chicago.” Roth led Cerny to more than one picker’s delight, including the trip that netted him a taxidermy menagerie of two-headed animals. There are hoarders, of course, along with numerous hustlers and plain-old characters who populate the weird world of resale and used stuff.

Cerny’s business partner Jeff Nelson, seen here at the Wrigleyville Antique Mall, circa 1990s. The two friends are still partners at the Broadway Antique Market.

And then there are the ghosts. In fact, at times, “Selling Dead People’s Things” almost reads like an anthology of ghost stories, such as the tale of the partner desk that Cerny has sold and refunded multiple times after customers got freaked out by the desk’s inexplicable habit of pushing open its own drawers, sometimes shooting them out of their glides with such force that they wind up on the floor. There’s the similarly possessed television set that won’t turn off, even when unplugged. And what’s not to love about the story of the mad-scientist doctor who haunts the former hospital where he performed experimental, and probably extralegal, limb-replacement surgeries on farm animals and dogs, the latter of whose ghosts periodically bark in the cavernous ruins of the very same hospital where both Hillary Rodham Clinton and John Wayne Gacy were born?

Cerny found this taxidermy of a two-headed calf on an outing with one of his favorite picking partners, Hy Roth. The story is described in “Selling Dead People’s Things.”

Cerny has heard those dogs bark; he’s seen the possessed television set in action. Cerney, in short, believes in ghosts, although not because he’s predisposed to a faith in the supernatural. “Some people are very intuitive and receptive,” Cerny tells me when we speak over the phone. “I’m not.” Nor does Cerny believe in classic Dickensian ghosts—floating apparitions clothed in white, draped in clanking chains, and lurking in shadows amid the living, who they mercilessly tease and torment. For Cerny, supernatural phenomena is more likely the product of what he calls “residual energy” from a “very powerful life force” that was somehow transferred to certain objects and places by the living.

“I have a friend who does not believe in this sort of thing,” Cerny says, “yet it happens to him all the time. I’ve seen him go into a vendor’s booth at an antiques show and pick something up. He’ll set it down, and five minutes later, somebody else is picking it up and buying it. I’ve seen that happen at least 10 times. For some reason, people are drawn to the objects he touches. I think there must be some form of energy that comes off of him, like a charge from a battery. When a person comes along who’s sensitive to that energy, they’re drawn to it. It kind of gives them a ‘spark.’ I’ve seen him do it again and again. I have no explanation for it, but I’ve seen it happen.”

One of Cerny’s first loves is Mid-Century Modern furniture. This desk is from the Broadway Antique Market.

Let’s say that’s actually the explanation. Does that mean the people who once sat at that haunted partner desk were perhaps overly aggressive with the desk’s drawers, so much so that the drawers continue to respond, as if by some sort of psychic reflex, to their unseen hands? Cerny does not claim to know. But again, for the sake of argument, if a buyer and seller agree that a particular desk is haunted by whatever means or mechanism, shouldn’t its price be greater than a dull, boring, regular desk lacking its own supernatural special effects?

Perhaps, but the trouble with haunted objects, says Cerny, is that you can’t guarantee they will always act haunted, performing on cue to the delight of would-be customers. That makes it difficult to charge a “haunted premium” on unpredictably supernatural goods. In addition, and this should not come as a surprise, the whole genre of haunted antiques is riddled with fraud.

Vintage lunchboxes have been an important part of Cerny and Nelson’s business since the 1990s.

“For quite a while,” Cerny reminds me, “people were selling ‘haunted’ dolls on eBay, and charging ridiculous prices for them.” The market for these dolls, he says, is the result of urban myths perpetuated by such cultural phenomena as the Chucky movies “and similar silliness. When talking to other dealers, though,” Cerny adds, “I do hear a lot of stories about haunted furniture, with the self-rocking rocking chair being the classic.” Still, these secondhand tales, and even Cerny’s firsthand experiences, are the exceptions rather than the rule. “For the book, I went with my best stories,” he says. “Some of them happened to be about haunted stuff. But it’s not like every time I turn around, the world gets all ‘Ghostbusters’ on me. I did my best to convey my experiences convincingly, but people can make up their own minds.”

Cerny calls barware like this cocktail shaker a “gateway collectible” because it brings customers into the Broadway Antique Market, where they invariably discover other stuff.

More common have been Cerny’s brushes with hoarders and their hoards. In “Selling Dead People’s Things,” Cerny takes us inside a few hoarder dens, describing the sights as well as the smell, which he says is “a vile mix of feces, mold, decay, and death.” In one chapter, Cerny tags along with a man named Marvin, who makes a living in one of the weirder corners of the real-estate industry by cleaning out the former homes of hoarders in order to make them presentable enough to sell. For Cerny, these trips into olfactory hell—Marvin rarely eats before a cleanout—hold the potential of one or two hidden treasures amid the garbage, or perhaps an entire cache of goodies that can be sanitized, disinfected, and resold. For Marvin, everything else is equal before the blade of his shovel. The work, we learn, is grinding and monotonous, and falls into two basic categories—ankle-deep or knee-high—referring to the height of the plastic garbage bags that Marvin wraps tightly around his legs to protect himself from the worst filth.

At some point, most serious collectors and dealers have their own hoarder moment, in which they consider, if only as a passing thought, whether their collection of porcelain signs, candlestick telephones, comic books, or sofas has become a hoard. Where does one draw the line?

“I think when you can’t have people over, you’re a hoarder,” Cerny says, as a prelude to story about a friend who was out and about one day when nature paid him a particularly urgent call. “He remembered that a friend of his, who’s another antiques dealer, lived around the corner, so he figured he’d ring his doorbell and ask if he could use his bathroom. That’s what he did, but when he opened his door, he just looked at him and said, ‘What are you doing here?’ He said hello and explained his predicament, but he gave him a flat, ‘No.’ He pleaded his case, saying, ‘You don’t understand. I really need to use the bathroom.’ Finally he told him to wait, shut the door, and then came back with a blindfold. He actually blindfolded him before he let him walk through his home, it was that crammed with stuff. So, yeah, when you can’t have people over anymore, you just crossed the line.”

Two of Cerny’s biggest influences were Tom Neniskis, who ran an antiques shop called Jacob Marley, and Hy Roth, who was an illustrator for “Playboy” and other publications.

Short of that line are the obsessives. “There is an almost erotic or sexual desire on the part of some people to flesh out their collections,” Cerny says. “People come into our store with spreadsheets—it’s the only way they can keep track of what they have and what they still need. Let’s say they’re looking for Russel Wright dinnerware: They’ll only fill in the holes in their collection based on the holes in their spreadsheet.”

How does it come to this? The reasons for an obsessive collection are as varied as the stuff available to collect. “I did a sale the other week of easily over a thousand monkey objects,” Cerny says. “There was monkey art, monkey glasses, monkey furniture, monkey cookie jars, just monkey, monkey, monkey you-name-it. Often there were multiple versions of the same monkey thing, because maybe the second one the person bought was in better condition than the first. The minutia of an obsession like that depends only on how far the collector is willing to go. And it all may have started very innocently; maybe somebody gave the person a monkey figurine as a gift, they loved it, and immediately started looking for more. It’s the same with beer steins, paperweights, anything. The stuff itself is interchangeable.”

Cerny says vintage fashion is another “gateway collectible” because people love to dress up. This feather hat is from Broadway Antique Market.

Still, even obsessives—“especially” obsessives, is probably more like it—need help managing their habits, and sometimes it takes more than just a spreadsheet to keep them in check. “We have people who come in,” Cerny says, “and they’ll say, ‘Do not let me buy anything today.’ And when they come up to the counter with something they want anyway, I’ll say, ‘No, you told me not to let you buy anything today.’ That’s the sort of intervention made by people who know themselves well. I’ll say, ‘Come back next week. If it’s here, it was meant to be.’”

Of course, not all obsessive-collecting stories have such happy endings. “I once had a customer who cashed in his 401(k) to buy a collection of comic books that he just had to have. He dropped like 70 grand. Now, maybe that would have been okay if he’d been buying them for an investment. But these were comic books he had when he was a kid, and he just had to replace them. Now he doesn’t have a 401(k). Obviously, that’s not really healthy.”

Lately, Cerny has been collecting photographs of obscure magicians. This is “Rosetti, The Great,” photographed in 1930 with an assistant and a portrait of Charles Lindbergh.

Cerny collects stuff, too, although he likes to think he has his obsessions under control. “My business partner likes to collect bedroom sets,” he says. “I tend to collect smaller things. I especially like paper and ephemera with one-of-a-kind images on them. Right now I’m collecting photographs of obscure magicians. I like the whole genre of bad vaudeville, the second-rate talents. People in the lower rungs of show business intrigue me, and the whole category is kind of lost to the collector world. People don’t know about it yet.”

Right now, according to Cerny, the hottest sellers are vinyl records, vintage barware, and vintage clothing, which Cerny calls “gateway collectibles. Drinking, dressing up, and playing music never go out of style,” he says. “That stuff really brings people into the Broadway Antique Market.”

“Selling Dead People’s Things” by Duane Scott Cerny is available from Amazon. (If you buy something through a link in this article, Collectors Weekly may get a share of the sale. Learn more.) For more information about the book and to read a sample chapter, visit the author’s website.

A good example of that gateway dynamic can be seen on Record Store Day. “We participated in that a month or two ago,” he says. “It was the 10th anniversary, and it was just crazy around here, a madhouse. So, people came in for that, but then they were like, ‘Oh, wait a minute. What’s this?’ Well, now they’re looking at souvenirs from a World’s Fair. ‘There was a World’s Fair in Chicago?’ Actually, we tell them, there were two, so we show them pieces from 1893, pieces from 1933. ‘This is really cool!’ And they end up buying something. Vinyl records got them in the door, it was the gateway, it opened them up to the world of vintage. From there, it doesn’t take much for them to see that they don’t have to buy horrible new junk from Wayfair.”

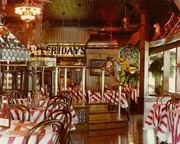

The Death of Flair: As Friday's Goes Minimalist, What Happens to the Antiques?

The Death of Flair: As Friday's Goes Minimalist, What Happens to the Antiques?

Could Your Stuff Be Haunted? Ghostbusting the Creepiest Antiques

Could Your Stuff Be Haunted? Ghostbusting the Creepiest Antiques The Death of Flair: As Friday's Goes Minimalist, What Happens to the Antiques?

The Death of Flair: As Friday's Goes Minimalist, What Happens to the Antiques? The Waiting Game: What It Really Takes to Get on 'Antiques Roadshow'

The Waiting Game: What It Really Takes to Get on 'Antiques Roadshow' Magic Posters and EphemeraThe Golden Age of Magic (1875-1930) generated thousands of colorful posters…

Magic Posters and EphemeraThe Golden Age of Magic (1875-1930) generated thousands of colorful posters… Mid-Century Modern FurnitureMid-Century furniture describes tables, chairs, dressers, and desks marked …

Mid-Century Modern FurnitureMid-Century furniture describes tables, chairs, dressers, and desks marked … TaxidermyTaxidermy evolved out of the tanning trade, whose practitioners preserved t…

TaxidermyTaxidermy evolved out of the tanning trade, whose practitioners preserved t… Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Another great article Ben. I went to his place. Amazing stuff.

Maybe I missed it, but what is the name of his (your) antique store in, I presume, Chicago? Thanks. –It’s the Broadway Antique Market, http://bamchicago.com/. – Eds

his appropriately creepy mustache….

Loved the book! I also grew up on the NW side in the 60’s and was also watching Bozo that day. The book was a blast from the past

Great article. I’m a Frank Sinatra fan/collector. When obtaining personal items, especially from people who loved them & kept them until their death, I always wondered about the possibility of spirits or energy (if you believe in that) attaching themselves to these items. My bedroom is covered with Sinatra’s shirts, jackets, boots, etc. Sometimes at night, I get strong smells of cigarette smoke even though he’s been gone for 20+ years. It’s never a scary feeling though, I almost feel protected around these things. All the items are covered in airtight covers. What are your thoughts?

The other day I was talking to a friend of mine about her idea for a new book. She wanted to write about hoarding, and she wanted me to help her research it.Hoarding is not in my wheelhouse, but it’s not hard to find out what the symptoms are. I’ve done some research on hoarding myself, and here are some of the symptoms:Belongings are kept in places where they won’t be used or seen. For example, if you have a room that’s just for bills, clothes, and other junk, then you’re probably a hoarder. I will have to visit https://www.proessaywriting.com/pay-someone-to-write-my-paper/ website for help in essay. If your garage is full of junk, even though you have no intention of ever selling anything there again, then you’re probably a hoarder too.

I have a number of theories about the origins of hoarding. My first theory is that when you hoard, you are trying to control your environment. You don’t want anything to be out of place. This means that if you die and leave things behind, you have a lot of extra room in your house.A second theory is that hoarding is related to mental illness. There are some people who are just inherently disorganized or messy and can’t keep their stuff in order, even if they try really hard. There are also some people who have mental illnesses that make them disorganized or messy, such as schizophrenia or bipolar disorder. It’s possible that some people with these illnesses end up with hoarding problems after they get better because they’re still having trouble getting organized and keeping their things in order.