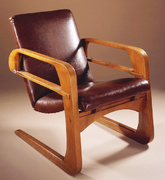

Ollie Johnston’s Kem Weber Compact Animator’s Desk. Courtesy of Mark Kirkland; photo © Dave Bossert.

In the summer of 1938, Walt Disney put $10,000 down on 51 acres of land in Burbank, California, for a new animation studio. At the time, Disney’s first full-length animated feature, “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs,” was on its way to grossing $8 million at the box office, a new record for a motion picture. But even before the financial success of “Snow White” was assured, Disney had pushed “Pinocchio” and “Fantasia,” into production at his company’s cramped Hyperion Studios—hence the need for a new animation facility in Burbank.

“It was the basic, Kem Weber Animator’s Desk, big, wide, and solid as a rock, like sitting at a monument.”

As a filmmaker, Disney always had big plans. As a builder, though, Walt Disney may have been even more ambitious, spending much of 1938 and ’39 consulting with his new studio’s architect, Kem Weber. Together, they created a work environment that was designed expressly for animators. Weber’s low-rise buildings, which quickly filled with the company’s roughly 800 employees, were sited to maximize northern exposure, ensuring optimal natural light for Disney’s small army of animators. Even the birch plywood desks these animators sat at were customized for their tasks, whether they were sketching storyboards, executing the entry-level grunt work of the “inbetweener,” or painting backgrounds.

Disney animator office with Kem Weber furniture, courtesy The Walt Disney Family Museum. Collection of Tony Anselmo; photo by Frank Anzalone.

In his latest book, Kem Weber: Mid-Century Furniture Designs for the Disney Studios, author and former Disney animator David A. Bossert offers fresh insights into the Disney-Weber relationship, particularly in the way it affected the half-dozen or so different desk styles Weber designed for character animators, layout artists, and animation directors. Naturally, Weber received a steady stream of input from Disney, but Weber also solicited ideas from one of the greatest animators of the 20th century, Frank Thomas, who used the prototype of the desk he helped Weber design—built by the Peterson Showcase & Fixture Company—to complete his work on “Pinocchio.”

As an animator, Bossert knows these desks well. “When I started at Disney in May of 1984 on ‘The Black Cauldron,’” Bossert says, “they showed me to an office and said, ‘Here’s your desk.’ It was the basic, Kem Weber Animator’s Desk, big, wide, and solid as a rock, like sitting at a monument. After a couple of years, I asked for something ‘a little more compact.’ For the next 30 years, I thought I was sitting at an assistant’s desk because it was so much smaller. That’s what I liked about it. It wasn’t until I was working on the book and got a glimpse of the original Weber blueprints that I found out it was actually called a Compact Animator’s Desk.”

Kem Weber (kneeling), Walt Disney (in hat), and Howard Petersen in 1939. Peterson’s company manufactured all of the Weber furniture for Disney’s studio. Photo © UCSB.

Each piece of Weber furniture had a different role to play in creating the trademark Disney magic. From a production standpoint, the process began at the Director’s Table and Story Desk. After an initial round of meetings with the film’s director at either a full size or smaller version of a Director’s Center Table, the storyboard artist would head off to his Story Men’s Sketch Desk, UNIT No. 21—as it was officially labeled on Weber’s blueprints—to rough out the sequence of scenes in the film, creating the roadmap animators would subsequently follow.

A key characteristic of the Director’s Table was its intentional placement in the middle of an office, so that numerous animators could gather around it—that’s why the table has the word “Center” in its official name. Drawers and cubbies on all sides added to its role as a hub for collaboration, and there were even stainless-steel-pipe footrests under both of the table’s wide sides, as if to afford the artists presenting their work the same level of ergonomic courtesy as the directors they reported to.

A Disney artist working on Fantasia (1940) at a Kem Weber designed Background Desk. Photo by Baskerville, © UCSB.

In contrast, Story Desks were smaller, more private spaces. Designed to face a wall, the desk’s 11.5 square feet of surface area could be tilted forward to face the artist. The desk also featured a circular pane of white glass inset into its birch surface, which allowed the 5-by-7-inch pieces of paper used in storyboarding to be illuminated from behind. For artists who did not require or want this feature, a thin sheet of Masonite was placed on top of the birch, giving animators a smooth, hard surface to draw on.

Once a storyboard was approved, character animators would get to work on the mice, ducks, elephants, hippos, alligators, flamingos, wooden puppets, and crickets that populated so many of Disney’s earliest films. Then, after “model sheets” showing all aspects and features of these characters received the director’s coveted A-OK, layout artists would begin the task of blocking each scene to determine where characters would stand, whether they would face each other when speaking, and the position of the sun or artificial light source. Once a character was drawn in a few key positions, the inbetweeners would undertake the laborious process of producing enough slightly different drawings of each character until, together, these drawings created the illusion of seamless movement when animated. It was only later that background artists gave the worlds these characters inhabited color and dimension.

Disney artists painting backgrounds for the “Pastoral” sequence in “Fantasia” (1940) at Weber designed Pan Tables. Photo by Baskerville, © UCSB.

Naturally, Weber designed specialized desks for all of these tasks, but he lavished extra attention on the Animator’s Desks, which could be configured in dozens of ways. Animator’s Desks could be raised at either their bases or between their bottom and top sections, which themselves came in various sizes (as we have already heard, Bossert preferred the desk’s compact version). Animator’s Desks could also be paired with other pieces of Weber furniture, such as a small paint table on wheels, whose top featured a circular indentation for a stoneware crock that artists would fill with water to mix and dilute pigments. There was even a portable Animator’s Desk on wheels for directors, many of whom were former animators—if a director was having trouble explaining what he wanted to an animator in words, he could always just pick up a pencil and communicate his vision in pictures.

Some of the coolest features of the Animator’s Desks, though, had nothing to do with the artistry and craftsmanship of animation, at least not directly. Consider the stainless-steel “cigarette guard” that protected the edges of certain shelves from burn marks, caused when animators would lay down a cigarette and then forget about it while they got lost in the details of a particular drawing. According to Bossert’s book, cigarette burns had been a big problem on desks in Disney’s Hyperion Studios, so much so that Weber included a stainless-steel cigarette guard in his design for the desks at the new studio in Burbank. (In 1939, the radical idea of going outside to smoke apparently did not cross anyone’s mind.)

Other design touches performed dual roles. While the desk’s recessed drawer pulls represented a handsome touch of Streamline Moderne for which Weber was so well known, they also made handy bottle openers for a late-afternoon beer. “I opened many a bottle on my drawer pulls,” the author confesses. Similarly, it was also apparently no accident that one of the desk’s cabinets was just the right height for a bottle of Scotch.

Top: Cigarette guard on an Animator’s Desk. Above: Construction detail of the “breadboard” drawer. Note the beautiful workmanship involved in the recessed drawer pull (and bottle opener), accented by the only use of paint on the furniture. Both photos © Dave Bossert.

For Bossert, his first Weber desk didn’t need to be stocked with Scotch to help get him through “The Black Cauldron,” whose crew he joined in 1984 as one of 28 special-effects animators. It was Bossert’s first animation gig after graduating from CalArts, an arts institute Walt Disney’s brother, Roy O. Disney, had helped establish in Valencia, California, in 1971.“I thought I was going to get laid off when the work of the special-effects department was done because I was one of the last guys hired,” Bossert says. “I had planned to work my tail off, save some money, and then hang out at the beach and figure out what I was going to do with the rest of my life.”

“When I left the company, there were only one or two Compact Animator’s Desks like mine in use.”

The Disney Studio, however, had other plans for Bossert. “They didn’t lay me off,” he says, still somewhat bewildered by the memory. “I was blown away by that. They said, ‘We’d like to hold on to you, but we don’t have a lot of work for you right now. Would you be willing to help out in the ink-and-paint department to finish painting cels for ‘The Black Cauldron?’ So, I became an inbetweener, an entry-level position, for a couple of months, and worked my way up from there. It was one of the best educations I could have had in animation.”

Even though “The Black Cauldron” almost sunk the studio—it was a spectacular financial flop in 1985—in retrospect the film signaled a rebirth for Disney Animation, thanks, Bossert, says, to the vision of Roy E. Disney, Walt’s nephew, who was the subject of Bossert’s Remembering Roy E. Disney: Memories and Photos of a Storied Life, published in 2013. During Roy E’s tenure, Bossert worked on such classics as “Who Framed Roger Rabbit?”, “Beauty and the Beast,” and “The Lion King,” as well as one of Bossert’s favorite films during his career at Disney, “Fantasia 2000.” “That one is near and dear to my heart,” Bossert says. “It wasn’t a huge box office hit, but artistically, I thought it was a beautiful movie, and it continued Walt’s vision of “Fantasia” as a celebration of music and visuals working together.”

Former Disney animator Dave Bossert still uses his Kem Weber Compact Animator’s Desk. Photo © Dave Bossert.

In the end, Bossert was able to take a physical piece of his 32 years at Disney home with him when he retired in 2016—he was given the Compact Animator’s Desk that he’d sat at for roughly three decades. “When I was packing up my office, the head of operations, who I’d known for years, came by. We were chatting about this and that when she said, ‘Hey, would you like your desk?’ I was a bit dumbfounded because there weren’t many people at the studio anymore who understood the significance of that particular piece of furniture.”

In contrast, many people at the studio had long understood the significance of Weber’s most famous 1939 Disney Studio design, the Airline Chair. According to Bossert, the company kept careful track of those vintage pieces of furniture because the originals routinely brought more than $15,000 each at auction. But the desks? Not so much.

“These desks are actually very rare, if less valuable than the chairs” Bossert says. “When I left the company, there were only one or two Compact Animator’s Desks like mine in use, and I only know of one other Compact Animator’s Desk outside the studio, Ollie Johnston’s, which is pictured in my book.” The problem was that the desks were simply too big for modern office floor plans. As a result, they had to go. “Sometime back in the 1960s,” Bossert continues, “the facilities folks at Disney actually took a couple truckloads of Weber desks to the dump and threw them away, which is crazy to me. Hundreds of years from now, that’s going to be an amazing archaeological find.”

(If you buy something through a link in this article, Collectors Weekly may get a share of the sale. Learn more.)

The Art of "Star Wars": The Force Behind the Most Iconic Image in the Cinematic Universe

The Art of "Star Wars": The Force Behind the Most Iconic Image in the Cinematic Universe

Kem Weber: The Mid-Century Modern Designer Who Paved the Way for IKEA

Kem Weber: The Mid-Century Modern Designer Who Paved the Way for IKEA The Art of "Star Wars": The Force Behind the Most Iconic Image in the Cinematic Universe

The Art of "Star Wars": The Force Behind the Most Iconic Image in the Cinematic Universe Dr. Seuss, the Mad Hatter: A Peek Inside His Secret Closet

Dr. Seuss, the Mad Hatter: A Peek Inside His Secret Closet Mid-Century Modern FurnitureMid-Century furniture describes tables, chairs, dressers, and desks marked …

Mid-Century Modern FurnitureMid-Century furniture describes tables, chairs, dressers, and desks marked … DesksDesks delineate personal spaces for their users, who stand or sit behind th…

DesksDesks delineate personal spaces for their users, who stand or sit behind th… Disney CollectiblesThe world of Disney collectibles encompasses millions of products associate…

Disney CollectiblesThe world of Disney collectibles encompasses millions of products associate… Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Extremely interesting article. Detailed but not scholarly. Enjoyed this very much. I think those artists, working at their Weber desks, were so skilled and very, very patient.

Thank you!

Gillian

In the lower left hand corner of today’s (1/5/19), I saw a preview article on Kem Weber and his designs for the Disney Animators’ Desk(s). I have a little anecdote to to Kem Weber and the desks. My father was one of the first Disney animator’s to work at one of Kem’s desks. My father, Volus C. Jones, was the youngest Disney animator to assist in the creation of “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs.” I have pictures of him working at his Weber desk in the Disney Studio. My father worked at the Hyperion Studio and moved with Disney to the new Burbank studio. Ironically, my was a non-smoker his entire life so the “cigarette guard” was of no use to him. On the other hand, the drawer that held the bottle of Scotch was used for my father’s Vodka bottle. Volus was called “ the Duck man” for his work on Donald Duck cartoons. He also worked on Bambi, Pinocchio and several other Disney creations.

I thought you might enjoy this little anecdote which makes the Weber Animators’ Desks a little more personal.

Delightfull/y, duty work stations! Gems in their heyday and still today; that’s if one can find it. As an artist and Art Teacher, my first ambition was to animate; it would be a thrill to purchase a Kem Weber animator’s desk.

I have a five year old girl mthat I know one day will enter California school of art and work at Disney Studios.

David Bossert,

It is important that you know there are people (like myself) who truly appreciate your article on Disney history and the Weber animator desk.

Thank you.

This look at the animator’s desk from Disney’s Golden Age is fascinating! It’s amazing how modernist design influenced the animation process during such a pivotal time. The attention to functionality and aesthetics really set the stage for creativity. Thank you for sharing this intriguing piece of animation history!

Great article and information. Very nicely done.