Immersed in the American West during the early 19th century, artist George Catlin made it his goal to capture idyllic scenes of nature, often featuring the frontier’s many Native American inhabitants. Catlin was concerned about the destruction white settlers would bring as they moved west from the urbanized East Coast, reshaping the landscape for agricultural and industrial uses, and he wanted to document scenes of indigenous life before it was forever altered. His artwork captures vibrant green vistas filled with Native Americans playing games, dancing, and performing religious rituals, or hunters chasing buffalo and taming wild horses.

“Native Americans would later be put on display like animals in a zoo.”

Within a few decades, concerns about the loss of our natural landscape would reach the highest levels of America’s government, and efforts to preserve this open space would begin gaining traction, starting with the preservation of Yosemite in 1864. Eventually, these lands would become the basis for our National Park system, a model that has since spread all over the world. And yet, the National Parks differed from Catlin’s earlier mission in an important way—they attempted to eradicate native inhabitants, rather than protect them.

Today, the foundational myth of America’s National Parks revolves around the heroic preservation of “pristine wilderness,” places supposedly devoid of human inhabitants that were saved in an unaltered state for future generations. This is obviously a falsehood: Places like Yosemite were already home to thriving communities that had long cherished—and changed—the environment around them. Catlin’s paintings are vivid reminders that the vast expanses of our western frontier were not empty, but rather brimming with human cultures.

Though the National Park Service prevented wholesale industrialization, they still packaged the wilderness for consumption, creating a scenic, pre-historical fantasy surrounded by roads and tourist accommodations, all designed to mask the violence inherent to these parks’ creation. More than a century later, the United States has done little to acknowledge the government-led genocide of native populations, as well as the continued hardships they face because of the many bad-faith treaties enacted by the U.S. government. This story is an elemental part of our National Park system, the great outdoor museum of the American landscape, but the myth continues to outweigh the truth. How did the National Park Service evict Yosemite’s indigenous communities and erase their history, and can it come to terms with this troubling legacy today?

Top: “Buffalo Chase with Bows and Lances” painted by George Catlin, 1832-1833. Via the Smithsonian American Art Museum. Above: “Mariposa Indian Encampment, Yosemite Valley, California” by Albert Bierstadt, 1872.

In an 1833 editorial, Catlin made a loose proposal for a new kind of American park, hoping that future generations would be allowed to visit native groups in their natural surroundings—“a nation’s Park containing man and beast, in all the wild and freshness of their nature’s beauty!” Catlin went on, describing “a magnificent park, where the world could see for ages to come, the native Indian in his classic attire, galloping his wild horse, with sinewy bow, and shield and lance, amid the fleeting herds of elk and buffalo.”

As author Mark David Spence points out, while Catlin was one of few Americans to propose protecting indigenous people, his imagined park would still have exploited native cultures. “Catlin’s vision of ‘classic’ Indians grossly ignored the cultural dynamism of native societies, and his park would have created a monstrous combination of outdoor museum, human zoo, and wild animal park,” Spence writes in Dispossessing the Wilderness: Indian Removal and the Making of the National Parks.

In contrast to the indigenous camp depicted above, Bierstadt’s 1865 painting “Looking Down Yosemite Valley” is a light-filled fantasy of “untouched” nature. Via Wikimedia. (Click to enlarge.)

Catlin’s ideas did eventually seep into the mainstream, and Native Americans would later be put on display like animals in a zoo. But first, “uninhabited wilderness had to be created before it could be preserved,” Spence notes. As Native American populations were murdered under the cover of Manifest Destiny, the idea of wilderness was twisted to mean a place before people, an idealized natural landscape that ignored the actual history of these magnificent places.

Despite the obvious claims of indigenous peoples to their lands, white officials frequently justified their removal by claiming that Native Americans weren’t good stewards of the new American frontier. In its excellent exhibition, “Nation to Nation: Treaties Between the United States and American Indian Nations,” the National Museum of the American Indian points out the myriad ways the United States government repeatedly lied about, altered, and disregarded legal contracts intended to secure native access to the land they already lived on. Beyond this egregious, criminal behavior on the part of U.S. officials, they also relied on written documentation, disadvantaging tribal officials who were accustomed to oral agreements or not fluent in English. Sometimes contracts were even negotiated by individuals that had no power to speak for their larger native community.

“Mouth of the Platte River, 900 Miles above St. Louis,” by George Catlin, 1832. Via the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Indigenous Americans eventually began referring to such treaties as “bad paper” because they learned the written contracts of European Americans were untrustworthy. But it wasn’t simply about miscommunication: Ultimately, the dispossession and genocide of native people was driven by white-supremacy, the idea that a “superior” civilization knew better how to utilize America’s vast land, and in particular, how to profit from it.

Journalist Samuel Bowles, who made several early trips to the West as the railroads were being built, captured the typical sentiments of white Americans toward Native Americans in his 1869 book Parks and Mountains of Colorado: “We know they are not our equals; we know that our right to the soil, as a race capable of its superior improvement, is above theirs; and let us act openly and directly our faith. … Let us say to him, you are our ward, our child, the victim of our destiny, ours to displace, ours to protect. We want your hunting grounds to dig gold from, to raise grain on, and you must ‘move on.’ … when the march of our empire demands this reservation of yours, we will assign you another; but so long as we choose, this is your home, your prison, your playground.”

Early images of Yosemite Valley, like this photograph by Carleton E. Watkins from 1861, capture a landscape that was cultivated by Native American inhabitants for thousands of years. Via the California State Library.

As the settlement of the western United States continued apace, Native Americans were systematically killed, enslaved, or pushed onto isolated and undesirable land by European Americans, who were privatizing most native land for profit. Support for excluding indigenous people from their homelands was also promoted by famous naturalists like John Muir, who held blatantly racist views about Native Americans. Muir and his cohorts never acknowledged that places like Yosemite, revered by European American visitors for its awe-inspiring “natural” appearance, had been shaped by centuries of native inhabitants who utilized controlled burning, horticulture, and other techniques to manage the ecosystem they depended on.

President Theodore Roosevelt and naturalist John Muir at Glacier Point in Yosemite, 1903. Muir’s views on conservation and Native American removal influenced the highest level of federal politics. Via the Sierra Club.

By the mid-19th century, American politicians were engaged in a debate over the preservation of our country’s natural wonders. Interest in outdoor recreation was on the rise, along with a nationalist pride in the country’s monumental landscapes. Yet many significant sites in the East, like Niagara Falls, had already been tarnished with industrial development, so the nation’s political leadership hoped new parks would be protected from too much human intervention.

While nearly every region destined to become a National Park was originally home to indigenous communities, the history of Yosemite clearly illustrates our government’s unjust treatment of the native people who called these spaces home. Several culturally distinct groups had inhabited the area over the last millennia, but by the mid-19th century, the Southern Sierra Miwok (and a subset known as the Ahwahneechee) were the most visible presence in Yosemite Valley, living alongside members of the Northern Paiute and Mono people. When the Yosemite Valley was first preserved for public use by President Lincoln in 1864 (giving the property to the state of California), much of the local indigenous community had already been devastated by a state militia group, the Mariposa Battalion, as a part of what is today known as the Mariposa War.

“Ma-ha-la of the Yosemite Band,” photographed by George Fiske, circa 1885. Via the California State Library.

After gold-mining camps steadily encroached into Native American lands along the Sierra Nevada mountains, several groups had fought back by raiding the Fresno River outpost of James Savage. In response, Savage organized a local militia group that chased the indigenous groups into the mountains and forced them into battle until the tribes surrendered. Surviving tribal members were forced to leave the region and move onto reservation land along the San Joaquin River in the Central Valley, though some hid in the mountains, hoping to return to their home.

“It was just a big mess,” Tony Brochini, a descendant of the Southern Sierra Miwok, says. “But that’s why we say that we never left Yosemite Valley.” Brochini, who was born and raised in Yosemite and worked for the National Park Service for 38 years, has long been involved with efforts by groups like the Wahhoga Committee, an organization of the area’s seven affiliated tribes, to re-establish indigenous cultural spaces within the park. Like dozens of other California tribes, despite their well-documented legacy, the Southern Sierra Miwok are still not federally recognized.

Left, a gathering at the Coulter and Murphy Hotel in Yosemite Valley celebrating the opening of Mariposa Road, 1875. Via the Online Archive of California. Right, the cover of a tourist map to Yosemite, circa mid-19th century.

The first year after its public designation in 1864, Yosemite only saw 147 visitors, though the numbers quickly multiplied as better rail access and tourist accommodations were established. (Although Yosemite was open for visitors in the 1860s, Yellowstone technically became the United States’ first National Park in 1872, with Yosemite following in 1890. Yosemite Valley and Mariposa Grove remained under state control until 1906, when they joined the rest of the park under federal jurisdiction.) Indigenous residents quickly assimilated to a growing community of white residents working for the Yosemite Valley’s various tourism operations by adopting European American clothing, food, and homes.

“The Yosemite probably constituted the largest native community in the central Sierra Nevada at this time,” Spence writes, “and their efforts to coexist with nonnative society actually preserved a high degree of cultural continuity and independence.” With Yosemite’s tourist economy booming and the valley increasingly overrun with development, native residents came to depend on employment at Yosemite’s hotels and concession businesses, or selling native crafts like woven baskets to visitors. “The hope of the Park Service was that the Indian community in the village would assimilate into the work culture,” Brochini says. “You either worked for the concessionaire or you worked for the government, and that was part of my legacy, working for the National Park Service as my father and grandfather did before me.”

A stereoview of a Paiute woman doing laundry in the Yosemite Valley. Photo by John P. Soule, 1870. Via the California State Library.

Unlike the pop-culture portrayal of Native Americans as violent “savages,” white residents in Yosemite generally viewed the indigenous community as mild, peaceful neighbors who provided much needed labor for park projects and tourism business. In fact, the park’s so-called “Indian Village” became one of Yosemite’s early tourist draws, such that acting superintendent William T. Littebrant urged the Secretary of the Interior to turn the Indian Village into a more prominent feature of Yosemite Valley, though little came of this exchange. Littebrant’s point was that the real native people living and working in Yosemite didn’t look sufficiently “authentic” to tourists who envisioned popular stereotypes and voiced their disappointment to park staff. Regardless, as Spence writes, “native people had become an important part of the tourist experience, whether as laborers in the valley’s growing service industry or as an authenticating aspect of the encounter with wilderness.”

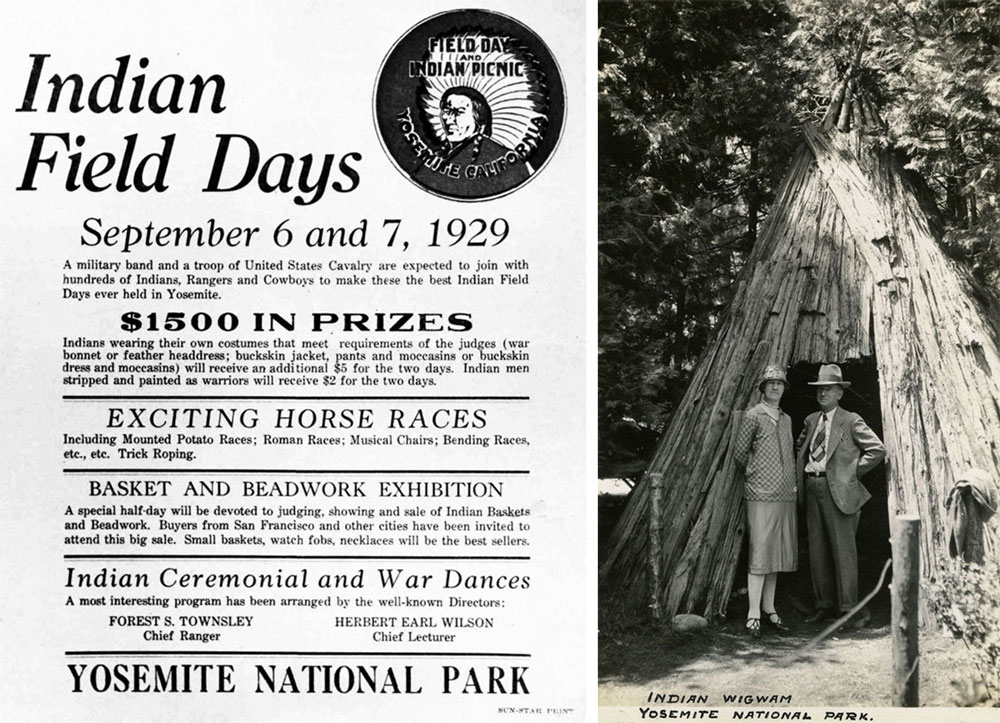

During the 1910s and ’20s, Yosemite hosted popular Field Days where white visitors could dress in stereotypical garb and indigenous employees were encouraged to act out white conceptions of native life. “Yosemite Park and Curry Company would dress up the Indians in the village with Midwestern headdresses and costumes and parade them around on horses,” Brochini says. “It was a big production, almost like a Barnum & Bailey sideshow.” These events stood in contrast to the indigenous community’s annual gathering known as the Big Time, a tradition centered on food and dance.

Left, a poster advertising Yosemite’s Indian Field Days in 1929. Right, tourists Grace and William McCarthy pose in front of a Miwok u’macha at Yosemite, 1935. Via the William M. McCarthy Photograph Collection, California State Archives.

In 1917, not long after the National Park Service was formally established, Secretary of the Interior Franklin Lane described it as a “national playground system,” emphasizing that these lands should be altered and developed to make them more accessible to the public, whether by cutting trees, building roads, or killing predators to increase popular game animals. Even as park officials sought to utilize the indigenous population as an “exotic” attraction for tourists, they simultaneously limited the use of park space for traditional tribal activities, including seasonal burns used to maintain open prairies and manage plant growth. Native American residents who broke park rules were subjected to particularly severe punishments, including lengthy jail sentences or expulsion from their homes in Yosemite. Unless under explicit supervision, park officials preferred to keep native residents out of sight.

“The Park Service didn’t want indigenous people to tell the public about how they were being treated.”

Indigenous survivors of the Mariposa Battalion had first resettled in the Indian Canyon area and remained there until the late 1920s, when park officials requested the native population move to a new location. This was ostensibly due to substandard living conditions, but more likely because the National Park Service planned to build a medical clinic on the existing village site. Brochini says his tribe’s matriarchs made the decision to move to an area they referred to as the “New Village,” where an ancient settlement called Wahhoga had once been.

On the Yosemite website today, the park service says that the Indian Canyon settlement was “disbanded,” rather than forcibly moved, and passively describes the indigenous community as shrinking. As is common on interpretive material regarding Native Americans, the National Park Service’s pressure on indigenous people to relinquish access to their land is masked by a blameless narrative of “natural” population decline and economic shifts.

This map of the Yosemite Valley illustrated by Jo Mora, circa 1940s, shows how the National Park Service used indigenous symbols to advertise the park even as Native American residents were being forced out. (Click to enlarge.)

By the 1930s, the governing view of Yosemite’s ecology was changing again: Park management began a push to restore the park to its so-called “pristine state” by managing wildlife and focusing on tastefully modified natural scenery, instead of increasing development of tourist facilities and roads. These goals reinforced official moves to restrict the indigenous population’s use of Yosemite’s natural resources, whether for hunting or sourcing plant foods, gathering materials for traditional crafts, or burning fires.

Yosemite’s new Indian Village was completed in 1931, and by 1935, all native residents had moved to the new accommodation—a total of 15 cabins for the community’s 66 permanent inhabitants. Along with this move, native residents were now required to pay rent to Yosemite, which gave officials even more control over their tenants. “That was our first real connection and acknowledgment by the Bureau of Indian Affairs,” Brochini says. “Everybody was assigned a cabin, but the Park Service charged everyone $5 a month to live there. They dictated who lived there, how long they lived there, and what happened to the buildings.”

Maggie Howard, known as Tabuce, preparing acorns in Yosemite. Photograph by Ralph Anderson, 1936. Via the Online Archive of California.

In 1953, Yosemite updated its policy regarding year-round residents, only allowing full-time employees and their families to remain. “It’s not totally well-documented, but from what I understand, there were Native Americans living there that had nothing to do with the park,” Yosemite Public Affairs Officer Scott Gediman explains. “The idea at the time was that if you were going to live here, you either have to work for the park or the concessionaire.”

“I’ve done a fair amount of research on it,” Gediman continues, “and basically, these were a bunch of cabins just west of Yosemite Village that were ‘temporary buildings.’ These were very simple one- or two-room structures that didn’t have bathrooms or plumbing. They weren’t built to be there forever. Around the mid-1950s, the entire National Park Service began what we called ‘Mission 66’ to take all of these temporary structures, like the housing, visitor centers, hotels, and build more quality, permanent buildings. So the idea was to get rid of this older village and have the Native Americans assimilated in with the rest of the park housing.”

The National Park Service’s “Mission 66” initiative led to a mini-development boom to accommodate hordes of tourist traffic, as seen in this Rondal Partridge photograph of Yosemite, entitled “Pave It and Paint It Green,” circa mid-60s. Via the Library of Congress.

In the mid-1960s, like many other Native American families, Brochini’s parents moved his family to Mariposa, a nearby town outside Yosemite National Park, for better job opportunities. As families relocated, either to official employee housing or out of Yosemite altogether, the Park Service destroyed their now-empty homes in the Indian Village, preventing indigenous residents from returning to the parkland. “We call it the ‘hidden agenda’ for the native people, to actually remove the indigenous people out of the parks,” Brochini says. “Systematically, they did that—not just for Yosemite, but for all the parks across the United States.”

“Uninhabited wilderness had to be created before it could be preserved.”

For decades, the park service had promoted the falsehood that native residents didn’t appreciate or respect the natural wonders in Yosemite. “Which is so peculiar,” Spence says, “because indigenous people saw stories of creation, of their history, of everything, in pretty much every feature of the landscape. I like to describe the landscape as their library, full of stories about good behavior, stories about the past, and models for the future.”

Even decades later, the park service is not forthcoming about its eviction Yosemite’s native population. “With housing more difficult to obtain, fewer Indian people came to Yosemite for employment,” the Yosemite website explains, conveniently sidestepping the park’s longstanding campaign to force Native Americans out of Yosemite Valley.

A Native American gathering near a cedar-bark u’macha near the Merced River in the Yosemite Valley. Photo taken by Eadweard Muybridge, 1872. Via the Online Archive of California, National Park Service.

“They didn’t want to share the stewardship,” Brochini says. “They didn’t want to deal with the Indian people and their living conditions, and having to talk about the history of atrocities in Yosemite or other parks, because I think in all the National Parks at some point in time, there was either militia or a battalion that went in and tried to remove people. The Park Service didn’t want indigenous people to tell the public about how they were being treated, and that’s basically what it all comes down to.” By 1969, only a few cabins remained in Yosemite’s Indian Village area, and officials relocated the remaining residents to government housing for park employees, using their empty cabins for firefighter training exercises.

Efforts to end indigenous residency and traditional land uses, combined with overdevelopment of new roads and buildings by the park service, also had the perverse effect of damaging the environment that had first made the Yosemite Valley so impressive to outsiders. Attempts by Yosemite staff to curb controlled burning inadvertently disrupted the area’s balance of species and made the landscape vulnerable to larger, more dangerous wildfires, like the record-breaking Yellowstone fires in 1988. “The reason Yellowstone burned insanely in 1988 was that park employees had been putting out lightning fires and native fires, too, not allowing anthropogenic fire in the landscape,” Spence says. “And you see that everywhere, every single National Park in California is profoundly affected by the absence of native burning.”

The ceremonial roundhouse at the Yosemite Museum’s reconstructed Indian Village dates from 1992. Via the National Park Service.

As Eric Michael Johnson reported for “Scientific American,” after 100 years of fire suppression in the Yosemite Valley, “biodiversity had actually declined, trees were now 20 percent smaller, and the forest was more vulnerable to catastrophic fires than it had been before the U.S. Army and armed vigilantes expelled the native population.” Johnson goes on to explain that the indigenous communities were “successful stewards of the forest, not because they had no impact on the environment, but because the forest was their home and they relied upon it for every aspect of their lives.”

Following the closure of Yosemite’s Indian Village in 1969, descendants from the Southern Sierra Miwok organized the American Indian Council of Mariposa County (AICMC) to advocate for themselves and strengthen the ties of their scattered community. During the 1970s, AICMC renewed the fight for access to Yosemite parkland where they could hunt and gather plants in a sustainable way and establish a cultural center as part of the park’s new General Master Plan.

Suzie McGowan carrying her daughter, Sadie, in Yosemite Valley, as photographed by J.T. Boysen, 1901. Via the San Joaquin Valley Library System.

“Two of our tribal elders—Jay Johnson and Les James—stood up to this group of congressmen and superintendents that came to create the General Master Plan,” Brochini explains. “The way Jay tells it, he says they couldn’t believe what they were hearing, Indians asking for their last village back.” After considerable discussion, the framework for a new cultural center on the former Indian Village site made it into Yosemite’s 1980 Master Plan. In 1987, the National Park Service produced its first Native American Relationships Management Policy, which committed to actively promoting tribal cultures as an important component of the parks.

Nearly 40 years after the original agreement, the cultural center has yet to be completed, but Brochini, Gediman, and others are hopeful that the traditional roundhouse will be finished sometime in the next year. “Right now, behind the Yosemite Museum is the Miwok Village with an authentic roundhouse and u’machas, meaning the Native Americans built them and use them, but the village was made for visitors, not for housing,” Gediman explains. “Since the 1970s, and even before that when the old Indian Village was removed at Wahhoga, it was the desire of the Southern Sierra Miwoks and other affiliated tribes to have a roundhouse and village in the location where it was for hundreds of years.”

While the new cultural center is constructed, Yosemite staff is also working to improve the bias present in the outdated historical materials posted throughout the park, as they opportunistically refurbish different areas. “One thing I’m really proud of is a huge restoration project at the Mariposa Grove of Giant Sequoias,” Gediman says. “I love to call it an ‘undevelopment project.’ That’s an area where there was a parking lot in the middle of the giant Sequoias—it was just very commercialized. We’ve removed the parking lot, the tram, and the gift shop. It’s going to reopen this spring, and on the new interpretive panels or displays, we talk a lot about the cavalry, Galen Clark, the military history, and the ‘white man’s version’ of history.

A postcard view of the famous Wawona Tunnel Tree in Yosemite’s Mariposa Grove. Cut as a tourist attraction in 1881, the tree collapsed in 1969, and is emblematic of Yosemite’s destructive development. Via Postcard Roundup.

“For the first time ever,” he continues, “we got together a working group with representatives from the seven tribes, and they told us the story of Mariposa Grove from the Native American perspective. The commonality between these groups is their connection to Yosemite, so to be able to get them all together and tell their stories through these panels is really exciting.”

Some of this progress was derailed by former superintendent Don Neubacher, who stepped down in 2016 after several years on the job amid a federal investigation into his “hostile” work environment. Despite this setback, Yosemite officials seem increasingly open to allowing indigenous access, such as the free permits issued to affiliated tribal members for gathering plants and using parklands for traditional ceremonies, like the annual walk across the Sierra to honor their ancestors. However, the growing number of visitors to Yosemite and structures needed to accommodate them continue to intrude into traditional indigenous ways of life.

“They’ve built right on top of areas that have grinding rocks and pounding holes, or spiritual and cultural areas that our people used long ago,” Brochini says. “They consult with the tribe before doing this, which is required by law, but they usually just take the information we provide and do it anyway.”

Today, the AICMC is still jumping through hoops to try and receive federal recognition for the Southern Sierra Miwok, though returning to live in the National Park is not on the table. “Yosemite Valley is our tribal land,” Brochini says. “If and when we become recognized as a tribe by the federal government, we’ll have to purchase land outside of Yosemite, but we’ll receive all the benefits of a federally recognized tribe and move forward by helping our people with dental and health programs, with land for housing, and any other economic development that would benefit the tribe. It would be a huge step for us.”

Lucy Telles with her baskets in Yosemite National Park, circa 1940s. Via the Online Archive of California, National Park Service.

Meanwhile, new experiments in shared stewardship between the federal government and indigenous communities are ongoing. In 2015, the Hopi, Navajo, Ute Mountain Ute, Ute Indian, and Pueblo of Zuni formed the Bears Ears Inter-Tribal Coalition to advocate for the creation of a new national monument in Utah. The following year, President Obama created the Bears Ears National Monument, along with a unique provision that the land be managed jointly by the Bureau of Land Management and the U.S. Forest Service, with input from a new commission, which includes a representative from each of the five tribes. Though Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke and President Trump have since attempted to pare down the size of Bears Ears, local tribes and conservation groups have filed lawsuits to block this encroachment.

Back at the Yosemite Museum, the path from native disenfranchisement to reconciliation is still uncertain. Objects belonging to Brochini’s ancestors are used to illustrate the park’s native presence, though mostly viewed in the past tense, as though his people were driven to extinction. “As you walk into the museum, on your left you’ll see a flat case, about 4-foot-by-4-foot,” Brochini says. “It has my great grandfather Bridgeport Tom’s rifle, and little snow shoes that he made. They’ve also got his moccasins and a cedar bow he used for hunting.”

The museum touches on the arrival of Lafayette Bunnell, James Savage, and the Mariposa Battalion, and the violent beginnings of Native American removal. But park employees like Gediman know there is room to improve, as the recognition of indigenous struggles to maintain a connection to their homeland is mostly lacking. “These are the kinds of things that the National Park Service can’t just gloss over,” Gediman says.

In fact, the museum’s timeline includes the 1851 invasion and murder of indigenous residents by the U.S. cavalry, but Brochini suspects most visitors are unaware of the sustained mistreatment of Native Americans by the National Park Service. “The interpreters don’t talk about that stuff,” Brochini says. “They don’t tell the real story.”

“Yosemite Valley from Artists’ Point” photochrom print by William Henry Jackson, circa 1898. Via the Library of Congress.

(For more information on Native American removal from Yosemite, check out Mark Spence’s book, “Dispossessing the Wilderness” and Carmen George’s coverage in the Fresno Bee. Other books on indigenous communities in National Parks include Robert Keller & Michael Turek’s “American Indians & National Parks” and Philip Burnham’s “Indian Country, God’s Country: Native Americans and the National Parks.” If you buy something through a link in this article, Collectors Weekly may get a share of the sale. Learn more.)

How Railroad Tourism Created the Craze for Traditional Native American Baskets

How Railroad Tourism Created the Craze for Traditional Native American Baskets

Why the 'Native' Fashion Trend Is Pissing Off Real Native Americans

Why the 'Native' Fashion Trend Is Pissing Off Real Native Americans How Railroad Tourism Created the Craze for Traditional Native American Baskets

How Railroad Tourism Created the Craze for Traditional Native American Baskets Before Camping Got Wimpy: Roughing It With the Victorians

Before Camping Got Wimpy: Roughing It With the Victorians Protest MovementsThe American Revolution began as an act of protest, so it follows that the …

Protest MovementsThe American Revolution began as an act of protest, so it follows that the … Native American BasketsBoth useful and beautiful, Native American baskets have been an indigenous …

Native American BasketsBoth useful and beautiful, Native American baskets have been an indigenous … Native American AntiquesThousands of years before America was “discovered,” Native Americans were c…

Native American AntiquesThousands of years before America was “discovered,” Native Americans were c… Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

There is no greater discrimination than that against Native Americans, Lone Wolf vs Hitchcock must be over-turned. They were here first, we are guests and very poor guest at best.

May also be of interest: http://www.environment.gov.au/topics/national-parks/kakadu-national-park/management-and-conservation/park-management

This is an important story and reminder of how much is yet to be done in honoring all American stories in our national parks, including our wrongs in places like Manzanar and myriad African and Native American sites of significance. It’s encouraging to see improvements and efforts on many fronts and I wish those efforts were acknowledged a bit more here. To see Jay Johnson and his son Phil use cultural practices to start management fires in Yosemite alongside today’s firefighters is inspiring. Perhaps the article could have linked to this video of that effort. https://www.nps.gov/media/video/view.htm?id=FCAB873A-03DC-D9A3-1F2FECA2217E4BAF The visitor center’s graphic large-scale depiction of the Mariposa Battalion burning tribal structures would also be a welcome addition to the article. While calling out the deficiencies and making a call to action we should also fully acknowledge the progress made to inspire more of it. Acknowledging and addressing more recent 20th Century Native American history, as we have done with racism related to black history for example, is a necessary next step. Just as Shelton Johnson cannot be the sole voice for black history in Yosemite, neither can Ben and Kimberly or Phillip and Julia be that for native people. The exhibits, films, waysides and more, developed in partnership and mutual respect, are a best practice to amplify.

To quote Pete Seeger…”when will we ever learn, when will we ever learn”.

‘Becky Stanford Says: To quote Pete Seeger…”when will we ever learn, when will we ever learn”.’

History would seem to indicate that we don’t learn, and if we do it is inevitably lost and forgotten. it is what we do as a species. we kill and destroy. and we will continue to kill and destroy until there is none of us left. so, at least there’s a happy ending.

This is a very timely article and well done. My own Anglo American family has 8mm, video only family films from the late 1950’s/early 1960’s. In one of those, we have traveled from Texas to one of the national parks. I am 8 to 11 years old, dressed in a full on feathered head dress, and dancing in a circle with some of the Native Americans (obviously hired) in the national park we were visiting. I remember to this day how embarrassed and self conscious I was, but somehow, I found myself doing such. The photograph of Ms. Suzie McCowan with her daughter, Sadie, is wonderful; I think I see what may be a weather shade of some kind above Sadie’s head. Excellent article!!! Keep up the great work, Hunter!

The article cites, the Southern Sierra Miwok (and a subset known as the Ahwahneechee, WRONG, the Ahwahneechee were Mono Lake Paiutes !