This article describes the evolution of the style and patterns of cut glass knobs, which came into use for drawer knobs in the 18th century, and notes some specific designs by Sandwich. It originally appeared in the May 1939 issue of American Collector magazine, a publication which ran from 1933-1948 and served antique collectors and dealers.

Just as brass handles, keyhole escutcheons and turned buttons replaced wooden knobs and wrought-iron handles on English and American furniture toward the close of the 17th Century, so glass came into use for drawer knobs about a hundred years later. The idea originated in England but spread rapidly to the United States, where glass handles were in great favor during the American Empire and early Victorian years. In the latter period the use of glass spread to such items of hardware as knobs for doors and cupboards and those essentials for controlling the elaborate window draperies, curtain tiebacks.

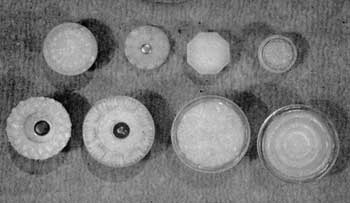

Eight Knobs of Opalescent Glass: Five of the designs shown are known Sandwich patterns. The others, because tint and fire of glass is identical, probably also came from there. Top row, left to right: Medium size with daisy design; button to be set in brass cup; six-sided flat knob for brass base (both from Sandwich); and very small floral knob. Lower row, left to right: Small diamond pattern; a popular conventional design; floral rosette also used for Sandwich tiebacks; and a circular design copied from brass knobs of the period.

Although the glass bureau knob in its various patterns was most widely used during the Empire and Victorian periods, it appears in earlier forms. First in England and later at Sandwich, glass knobs were made in patterns that definitely followed those shown in the plates of furniture design by both Hepplewhite and Sheraton. I have never seen glass drawer knobs in actual use on English Hepplewhite furniture, but several examples of rosette drawer knobs are shown in his Cabinet Maker and Upholsterer’s Guide which could well have been made either of hollow brass or of spherical shaped glass.

The earliest knobs, in fact, that I have been able to discover appear on that phase of Sheraton furniture known as Regency, and they are cut glass of the type made during the late 18th and early 19th Centuries at Bristol, and other English glasshouses, as well as those of Waterford, Cork, and Dublin.

These English-cut knobs appear in two shapes. Originally, balls of glass, then given many small facets by wheels grinding and polishing, some retain their spherical form; others are more octagonal. Both are drilled for a small bolt, usually having a polished brass head, by which the knob is attached to the drawer front. Such knobs are generally small and are found on delicate pieces, such as work and writing tables, lady’s desks, and the like. The larger cut-glass knobs, suitable for chests of drawers and similar pieces, are usually eight-sided, spool-shaped, and hollow. These, too, are held in position by a bolt with a large, ornamental head.

Fragments from Sandwich: Upper row, left to right: Conventionalized floral designs in opalescent, canary-yellow, and dark-blue glass. Lower row: Large rosette knob with glass screw shank (not found at Sandwich but attributed to it), broken, ribbed mushroom knob, and small knob with screcw-threaded shank. The last two are of clear glass that has become frosted from being buried in the ground.

Both large and small knobs were made more often in clear glass, but I have seen examples in deep blue, pale green, and delicate yellow. At best, however, these cut-glass knobs were in the nature of a novelty and not widely used. Also, since collectors of English furniture in Great Britain and the United States have long shown a disregard for pieces so fitted, dealers have often substituted the more orthodox brass rosettes for the original glass handles. It is equally possible that many other glass-knobbed pieces were refurbished with brass hardware at the hands of private owners who felt that they were materially improving the appearance of the piece by changing it from something unusual to the typical by such substitution. At any rate, the result is few pieces of English furniture with original glass drawer pulls.

But in the United States, the vogue of the glass knob was far wider spread and lasted longer. It began with crudely cut knobs, not at all like the fine work of England or Ireland, and continued through a distinct group of designs of glass cast in iron molds. Among the latter was an attempt to simulate an eight-sided cut-glass knob with diamond-shaped facets. One has only to handle it to realize that it was cast, not cut, as the edges of the facets are slightly rounded instead of true and sharp. Also, no effort was made to polish the bolt hole; therefore, the frosted effect shows plainly through the clear glass. I do not know where this knob was made but am of the opinion that it represents a very early American attempt, possibly contemporary with English cut glass knobs.

Fragments from Sandwich: Upper row, left to right: Conventionalized floral designs in opalescent, canary-yellow, and dark-blue glass. Lower row: Large rosette knob with glass screw shank (not found at Sandwich but attributed to it), broken, ribbed mushroom knob, and small knob with screcw-threaded shank. The last two are of clear glass that has become frosted from being buried in the ground.

Shortly after the cast-glass process was perfected by Deming Jarves at Sandwich, Massachusetts, knobs in several patterns became one of the standard products of the Boston and Sandwich Glass Company. There can be no question about this. For among the wide range of Sandwich fragments recovered by Mrs. Ada Danforth, Mrs. Ruth Webb Lee, and others from the site of the Sandwich factory, are a number of typical American patterns of knobs. When these are compared with original glass knobs on pieces of American Empire furniture, it is surprising how many of the designs are those represented by the Sandwich fragments.

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology also has a collection of Sandwich fragments retrieved from beneath the floor of one of the factory’s lehrs when it was wrecked for its brick. It includes a number of broken knobs. All of which make it evident that making drawer knobs was part of the regular commercial production of Sandwich. And from the fragments that I have been able to study, a number of facts are evident.

First, these knobs definitely followed the patterns of the brass rosettes then being made by the brass founders of Birmingham, England, and elsewhere. Next, the Sandwich knob designs, although contemporary with lacy glass, rarely had any detail that could be so considered. On the contrary, the details of these glass rosettes hark back to the details of brass knobs found in the furniture designs of Hepplewhite and Sheraton.

The latter were undoubtedly the inspiration of the Birmingham cabinet brass makers and indirectly passed on to Jarves and his mold makers when the making of glass knobs was initiated at Sandwich. For example, a Hepplewhite sideboard design shows a knob bearing on its face a conventionalized aster and there is a faithful copy extant in a Sandwich fragment. Further, in Sheraton’s Cabinet Maker and Upholsterer’s Drawing Book, third edition, London, 1802, in a plate of carved chair legs, may be found two ornamental rosettes as the upper element in the decoration. These appear directly or indirectly in Sandwich knob designs. Melon shaping achieved by concaved reeding was a favorite motif with Sheraton. This is represented by a Sandwich knob fragment in clear glass though now iridescent from being buried for years:

Five Early Cut-Glass Knobs: Left to right: Simple cut knob, probably American; large, hollow English spool type cut and polished both inside and out; six-sided with stem and two small spherical knobs cut with many facets. All are of clear glass.

In addition to the conventionalized aster design, already referred to, there is another favorite somewhat like the daisy and petals or rays radiating from a central dot which shows up as the central element of many pattern plates made at Sandwich in various sizes from the cup plate up.

Judging from the number of fragments of the same pattern that I have seen, one of the most popular Sandwich knob designs was a conventionalized flower with a small star center having six or eight rays surrounded by six or eight petals that in outline are almost like the crown used at coronations at Westminster Abbey. The number of rays and petals, of course, vary with the size of knob. Another had a roselike center with six petals. This design, a little further stylized, is to be found in glass tiebacks, also attributed with reasonable safety to Sandwich.

That they had many molds, and that those of the same pattern differed in detail, is brought out by comparison of various fragments. Design elements vary slightly; some are flatter, possibly due to a worn mold; others are in high relief, which may reflect a sharply cut new mold. From the marks it is evident that these floral knobs were all cast in three-piece molds.

Also the favorite method of supplying the knobs with screws was to embed them in the glass itself. This was done by casting the knob with a central bolt hole that extended into the knob about half way from base to face. Then lead was placed in the hole, which was scarcely larger than the rod of the headless bolt. When screwed into position, the lead being a soft metal made the knob fast and firm on the threaded bolt, so that when put in place and the nut turned tightly against the inner side of the drawer front, the knob was held securely in position.

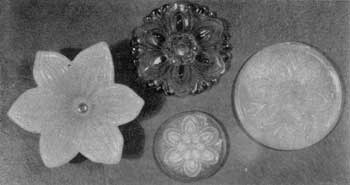

Four Sandwich Tieback Rosettes: Except for the one in the upper center, all are of opalescent glass. That at the lower left is a copy in glass of the clematis flower. The others are all of the same conventionalized floral design but show minor variations.

Other Sandwich knobs were cast with a central hole and a bolt with ornamental head was used, as with the English cut glass handles. In still another type made there was a knob with threaded glass screw. It was, of course, akin to the wooden knobs then being made in which there was a screw projection of coarsely threaded wood, knob and screw being turned from a single piece of wood. Both are much more unusual than those with iron bolt or screw.

Sandwich not only made a variety of knob designs but used glass in several colors besides clear. Fragments of proven origin include deep-blue, emerald-green, canary-yellow, milk-white, and opalescent glass with bluish fire. In fact, I have seen so many opalescent fragments that I am inclined to hold that this and clear glass were most frequently used at Sandwich. The knobs varied in size from small ones, an inch in diameter and evidently intended for interior desk drawers, to the largest which were two and a quarter inches in diameter. There was also an intermediary size measuring one and a half inches.

Although Sandwich probably did not make all of the glass drawer pulls used by American cabinetmakers during the Empire and very early Victorian style periods, I believe there were few designs not produced there. Of course, it must have had other New England glass factories and quite probably those of the Pittsburgh district as competitors. These knobs were in great demand and other American factories must have produced them and often copied designs originated at Sandwich.

Eight Designs of American Cast Knobs: All are of clear glass. Top row, left to right: Ribbed mushroom design; hollow rosette type and broken knob of same design showing hollow center; swirled mushroom; and design imitating cut glass. Lower row, left to right: Design of fine diamond shapes surrounding deep central cup; hollow crown-shaped rosette; swirl ribs on flat face and conventionalized floral design, also found on Sandwich glass tiebacks.

One knob which I believe to be of Sandwich origin, though not yet proven, is of clear glass with a concaved face in which the design is very close in feeling to lacy Sandwich. Surrounding the bolt head is an eight-pointed flower. Between this and the ribbed rim are two circles of eight diamonds. The inner is cross-hatched and the outer depressed, resembling the diamond daisy design of the Stiegel-type perfume bottles. The base is slightly depressed and decorated with sixteen rays that can be seen through the clear glass.

Four others in clear glass and one in opalescent which I am also inclined to attribute to Sandwich are: a knob one and three-quarter inches in diameter with a swirled ribbing extending back to the base; a knob with concaved face having ten raised ribs which curve arclike from the pewter bolt head to the rim; a conventionalized petal-shaped rosette with large, tapering glass screw; another with a deep central depression or cup one and one-quarter inches in diameter surrounded by a pattern of small diamond shapes which extend to the rim and part way down the side (I have seen fragments of this also in opalescent glass); and an opalescent knob with sunken center in which a central button is surrounded by a series of four circular ridges. This last, as well as the others, are of designs which were also made in the stamped brass rosettes.

Two other designs which I believe are of American origin are most unusual because they are hollow. They are of clear glass with central bolts. One has a petal design; the other has eight arched flutings that form the face of the knob.

Cut Glass and Cast Compared: The two with cut-glass faces are mounted in brass bases. One retains the reflecting mirror behind the glass so that it appears to be of opalescent glass. At the right a cast-glass knob of intricate geometric pattern that seems to be also of lacy Sandwich in its design.

Sandwich also made various designs of doorknobs. Many years ago, when the stock of the factory’s lamp salesroom in Boston was sold, several examples were included and A. Stainforth of the Boston Antique Shop bought them. They were intended to be mounted in brass sockets, and the bases had depressions for this purpose. Two specimens are cut glass, one octagon and the other circular with eight quarter-round notches and the face a large conventionalized four-leaf clover. Two others are cast glass octagons, one of milk-glass and the other apple-green. There are also two octagon-shaped knobs with fiat faces in opalescent glass, and in clear glass a plain cast knob of mushroom shape.

I have also studied an unusual type of cut-glass knob in which a cresting disk forms the face and is set in a brass base. The cutting design is geometric, like that of fine decanters of the early 19th Century. Behind the glass is either a disk of mirror glass or of Sheffield plate. Such knobs measure two and one-quarter inches in diameter and were intended for doorknobs and drawer pulls. The fine workmanship and brass base would indicate English origin, but very excellent glass cutting was done at Cambridge in the factory of the New England Glass Company.

This article originally appeared in American Collector magazine, a publication which ran from 1933-1948 and served antique collectors and dealers.

20 Halloween Costumes So Unsexy, They're Downright Scary

20 Halloween Costumes So Unsexy, They're Downright Scary David Lance Goines Discusses Perfect Poster Design

David Lance Goines Discusses Perfect Poster Design Meet the Swedish Artist Who Hooked British Rock Royalty on Her Revolutionary Crochet

Meet the Swedish Artist Who Hooked British Rock Royalty on Her Revolutionary Crochet These People Love to Collect Radioactive Glass. Are They Nuts?

These People Love to Collect Radioactive Glass. Are They Nuts? Rise of the Machines: Tractors and the End of Rural America

Rise of the Machines: Tractors and the End of Rural America Cut GlassWhile cut glass has been produced for thousands of years, it reached a peak…

Cut GlassWhile cut glass has been produced for thousands of years, it reached a peak… Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

I have seen these knobs still made in the USA by Look In The Attic. They also own the sandwich glass curtain tie back moulds and dozens of glass moulds. Great information and a great article!