The Tahiti, seen here sailing on San Francisco Bay, was a 124-foot brigantine built by Turner Shipyards in 1881. Courtesy Hunt Family.

In 1849, when word reached Ohio that gold had been discovered the year before in California, there was little to keep a young ship captain named Matthew Turner (1825-1909) close to the family homestead on the shores of Lake Erie. Eight years earlier, when Turner was just 16, his 36-year-old mother was taken by illness; in 1849, when Turner was a 24-year-old newlywed, his bride died, too. And so, in the winter of 1850, Turner bid adieu to his father, brother, and sisters and caught a Mississippi River steamboat for New Orleans. There, he secured passage to Panama and crossed the isthmus, probably by donkey, which saved him a solid three months of travel compared to sailing through the Strait of Magellan at the southern tip of South America. By May, before California was even a state, Turner had arrived by schooner in San Francisco, the rowdy gateway to the even rowdier goldfields lying east in the Sierra foothills.

“The story goes that he was so brokenhearted after the death of his wife and child, he just disappeared.”

Unlike most of his fellow prospectors, Turner did well during the California Gold Rush, parlaying his earnings into a string of profitable seagoing businesses and onshore enterprises, culminating in the Turner Shipyards (1868-1907). As the head of that company, Turner designed and built some 200 wooden sailing vessels, more than any other U.S. shipbuilder of the late 1800s.

A century after Turner left Ohio, another sailor would make his way down the Mississippi. The year was 1962 and the sailor was Alan Olson, who, along with his then-wife, Marsha, motored an unrigged, 40-foot plywood-and-fiberglass catamaran he’d built in Minneapolis all the way to Pensacola, Florida. Olson spent more than a year installing the mast and rigging the sails before he and his wife sailed the catamaran to the Bahamas with some friends. After a hurricane chased them back to Miami, the young couple settled into the drudgery of school and jobs, a rude come-down from the freedom of sailing on a whim between tropical islands. But like Turner, Olson would head to California, where he’s lived a life that’s revolved around a love of sailing ships and the sea since the 1970s.

This painting of Matthew Turner in his later years is still in the collection of Turner’s descendants. Courtesy Hunt Family.

Today, the legacy of Matthew Turner and the life of Alan Olson have intersected in the form a 132-foot-long brigantine named after the great 19th-century shipbuilder and sea captain. That’s because for the past decade or so, Alan Olson has been in charge of the construction of the Matthew Turner for Call of the Sea, a Sausalito, California, educational organization he cofounded in 1985. A hybrid of 19th-century design and construction techniques, as well as 21st-century technology, the Matthew Turner will introduce students of all ages and backgrounds to the experience of being on the water, where they’ll learn about nautical history, sailing science, ocean ecology, and, above all, the importance of teamwork.

Matthew Turner would have loved the idea of a ship designed for young people being named after him. That’s because despite losing his wife at a young age and never fathering children of his own, Turner ended his years a devoted family man.

The shift in his familial fortunes occurred in 1878, when, at the age of 53, Turner married into a family of three children between the ages of 6 and 12. The mother of the boy and two girls was Ashbeline Rundle, the widow of an Englishman named Richard T. Rundle, who had passed away two years earlier. Turner and Rundle had known each other since 1850, when they met in the rough-and-tumble goldfields of California. They spent several years battling rock and the elements in their quest for gold, and stayed in touch thereafter as friends and business partners. In fact, the two men were so close that in the 1870s, Turner, a bachelor since the death of his wife a couple of decades earlier, rented a room in the Rundle home at 711 Tennessee Street, not far from Turner’s first shipyard in San Francisco, making him a familiar part of the Rundle household.

Alan Olson aboard the Matthew Turner, which will begin educational sailing trips this fall from its home base in Sausalito, California.

Eileen Hunt, who is the great-granddaughter of one of the Rundle daughters, Charlotte, thinks she knows why Turner offered Ashbeline his hand in marriage after a suitable period of mourning. “He’d promised to take care of Rundle’s family,” she says. “From what I understand,” she adds, “there wasn’t a romantic relationship between Turner and Ashbeline, but Turner loved those kids.” Hunt also has a hunch as to why Turner took so long to remarry. “Perhaps he didn’t want to take the leap again,” she says. “Maybe the hurt of losing his first wife was too great.”

The hurt had occurred in Geneva, Ohio, where Turner’s father, George Turner, had settled from Connecticut around 1820; Connecticut had only ceded its claim to this portion of Ohio in 1800, so the ties between the two states were still strong. Upon arrival in what some people still called the Western Reserve, the elder Turner found employment as a deputy to Q. F. Atkins, the auditor of Ashtabula County, which is bordered on the north by Lake Erie and on the east by Pennsylvania. In 1822, Turner married his boss’s oldest daughter, Emily Atkins, purchased a farm in Geneva from Q. F., and began raising a family. By the year Matthew Turner was born, 1825, Emily had already given birth to a boy, Horatio, and two girls, Phedora and Stella. That was also the year that George Turner dammed Indian Creek, which flowed through the couple’s property, and constructed a sawmill.

Matthew Turner (left) and Ben Crocker (right) panning for gold on San Antonio Creek near Columbia, California, 1850. Courtesy Hunt Family.

George Turner’s timing was opportune. In those days, settlers in the young state of Ohio were transitioning from the log cabins that had been hastily erected to shelter them from the bitter winter winds blowing off Lake Erie to proper homes built out of lumber. Turner’s sawmill served this growing market. To increase the profitability of his sawmill, Turner commissioned the construction of two wooden sloops, the Geneva (1839) and the Philena Mills (1846). These ships allowed him to deliver his lumber to townships along the western shores of Lake Erie, and when his sloops returned with full loads of western Ohio limestone for local building needs, that put George Turner in the shipping business, too.

For about a year, Turner’s old brother, Horatio, captained the Philena Mills. For his part, Matthew had already begun his maritime career. By 1843, at the age of 18, Matthew Turner had earned a master’s certificate to captain seagoing vessels, the documentation required to command commercial ships on the “inland oceans” known as the Great Lakes. But Horatio’s younger brother took his interest in seafaring a serious step further when, in 1847, the ambitious 22-year-old designed a schooner of his own. His father and a business partner agreed to fund the construction of young Turner’s schooner, which was built out of lumber from his father’s sawmill. Soon, Turner was the captain of the George R. Roberts, as his two-masted schooner was christened, hauling timber west across Lake Erie, north to Lake Huron, and then south on Lake Michigan to Chicago.

From 1852 to 1853, Matthew Turner and Richard Rundle were partners in this gold mine at Big Oak Flat, California. Courtesy Hunt Family.

It seemed as if Matthew Turner had found his calling behind the wheel of a ship, and his marriage in 1848 to Amanda Jackson should have been the icing on the cake. But when Turner’s new bride and their baby died during childbirth, Turner became terribly distraught.

“The idea of a finer, narrower, bow was something that had been understood by designers of racing boats and yachts, but it hadn’t really been applied to the commercial side of shipbuilding.”

“The story goes that he was so brokenhearted after the death of his wife and child, he just disappeared,” Eileen Hunt says. In fact, Turner left Geneva aboard the George R. Roberts without so much as a goodbye. As it turned out, Matthew went off to haul lumber on Lake Michigan, but George and Horatio Turner were so concerned about their son and brother’s months-long absence that they posted advertisements offering a reward for information about Matthew Turner’s whereabouts in newspapers from Detroit to Cleveland. In the end, Turner returned home, unaware of the anxiety his disappearance had caused. But the episode suggests that in some form or another, Turner was done with Geneva, Ohio, and why, in 1850, the young man was so eager to make his way to the goldfields.

Once in California, Turner joined forced with Ben Crocker, sluicing and panning for gold on San Antonio Creek near the town of Columbia. At some point, he parted ways with Crocker and partnered with Richard T. Rundle, who, like Turner, was also a sea captain. Turner and Rundle worked a small mine near Big Oak Flat. While most people lured to California to strike it rich lost their shirts, Turner did very well in his three-and-a-half years of prospecting, turning his gold into a schooner called the Toranto, which he promptly sailed to California’s densely forested northern coast to resume the lumber-hauling business he’d practiced on the Great Lakes. This time, though, Turner’s market was San Francisco, which by 1853 was a roaring Gold Rush boomtown that gobbled up building materials like lumber as fast as it could be unloaded from the holds of schooners like the Toranto. Soon, Turner was transporting lumber and other goods aboard the Toranto to markets as far away as Tahiti, where he went into business with Benjamin Franklin Chapman.

In 1853, Turner parlayed the money he’d made as a gold prospector into this ship, the Toranto, which he used to haul lumber from Mendocino County to San Francisco. Courtesy Hunt Family.

This would not be the last time the Chapman and Turner families would cross paths. Benjamin Franklin Chapman’s son, Adrienne Eugene “Charlie” Chapman, would marry Charlotte Rundle Turner, one of Ashbeline’s daughters and Eileen Hunt’s great-grandmother. Given his connections to the Chapman family, Turner may have been the one to make the introductions. “There was so much intertwining between our families,” Eileen Hunt says.

Over the next decade and a half, Turner followed opportunities wherever the schooners and brigantines under his command took him, from the Strait of Magellan to the Gulf of Alaska. With San Francisco, California, and Papeete, Tahiti, as his home bases, Turner’s life on the high seas was followed by a career of almost 40 years in California as the most prolific shipbuilder of his era. At the height of his shipbuilding career, in the 1880s, Matthew Turner was responsible for the design and construction of as many as a dozen schooners, sloops, brigantines, and steamers in a single year.

Matthew Turner at age 28, shortly after retiring from the life of a gold prospector. Courtesy Hunt Family.

In contrast, Alan Olson moved through the world at a more deliberate pace. After settling in San Francisco at the end of the 1960s, Alan Olson spent six years building the follow-up to his 40-foot catamaran. His sophomore ship was a 70-foot brigantine, which he began working on in 1971. Dubbed the Stone Witch, Olson’s brig finally left the dock in 1977.

To recoup some of his construction costs, Olson conducted educational programs on basic sailing principles and ocean ecology for students, as well as charter cruises for adults. Mostly, he sailed around San Francisco Bay, but Olson also took the Stone Witch down to Mexico and out to many of the same remote Pacific Ocean isles that Turner had visited 100 years earlier. Over the next decade or so, well into the mid-1980s, Olson sailed his brig more than 40,000 miles. For a while, the Stone Witch was even a flagship for Greenpeace, performing environmental missions along the California coast.

In 1985, these social-minded impulses led Olson to join several other sailors who were starting an organization named Call of the Sea, a nonprofit devoted to hands-on educational programs like the ones Olson had been offering aboard the Stone Witch. From around 1986 to 2000, Call of the Sea operated a 54-foot staysail schooner called the Maramel, which Olson had restored and remodeled to be a floating classroom. In 1992, he led a group of passengers aboard the Maramel on a 12-month, 15,000-mile voyage that followed the fault lines, ocean trenches, and volcanoes of the Pacific Rim. In 2007, Call of the Sea expanded its programming by purchasing an 82-foot, steel-hull staysail schooner called the Seaward, which today carries some 5,000 students a year onto San Francisco Bay, where they learn about everything from navigation to the impact of microplastics in the marine environment. This fall, when Olson and his team complete work on the Matthew Turner, Call of the Sea’s programming capacity will triple.

The Matthew Turner (left) and Seaward are operated by Call of the Sea, whose mission is to educate students of all ages about sailing and the sea.

While it would make a nice, tidy story to paint Alan Olson as a 21st-century update of 19th-century Matthew Turner, the differences between the two sailors are greater than the similarities. Consider the names given to their first vessels: Turner’s, the George R. Roberts, took its name from a business associate of his father, George Turner. Inasmuch as the elder Turner had funded the construction of his son’s first schooner, the decision about what to call the ship was simply not Matthew’s to make; no record exists of how young Turner felt about the name one way or the other.

In contrast, Olson put a lot of thought into the name of his catamaran, the Excitandum, the Latin word for “excite,” although at the time, Olson, who’d studied Latin in Catholic prep school, viewed the word in the context of its related and more romantic sentiment, “awakening.” Even more romantic was the inspiration for the Excitandum itself, as Olson explains to me when we meet aboard the Matthew Turner, which is buzzing with volunteers.

“When I was 16,” he says, “they used to have a show on TV called ‘Bold Journey.’ On each episode, different people would have different adventures. The one that stuck with me was about these six guys who called themselves the Six Magellans. They bought a schooner and sailed it around the world. Well, I couldn’t think of anything better to do than that.”

A TV show in the late 1950s called “Bold Journey” was the spark that ignited Alan Olson’s interest in sailing.

Unfortunately, the “Bold Journey” that had captured Olson’s imagination was an expensive one, the sort of thing six rich Magellans would do, not a kid of average means from the Twin Cities. Stymied by a lack of resources, Olson worried his dream would slip away until an acquaintance suggested he build a fiberglass catamaran. “He said, ‘You can order plans and parts from a guy in California,’” Olson remembers. “‘It’s cheap and easy. Anybody can do it.’ So I decided to do that.” Two years later, Excitandum was ready to launch down the Mississippi. “We didn’t have any rigging on it at that time,” Olson says, “but I was ready to get going.”

Ready for his awakening, you might say. “That was kind of the idea behind it,” Olson confirms. “I was going out into another world to kind of wake up, to find out what was going on. It’s a Buddhist thought,” he adds. “At the time, I didn’t realize how much Buddhism would influence my life. I’ve been very involved with Buddhist philosophies ever since.”

Just as there’s no record of what Matthew Turner thought about the name of his first schooner, we also don’t know a thing about his views of non-Western religions such as Buddhism. What we do know is that after Turner’s success with the Toranto from 1853 to 1855, he acquired a larger schooner, the Lewis Perry, which he used to haul goods between Chile and Argentina through the Strait of Magellan. Turner lived in South America for much of 1856, during which he and the crew of the Lewis Perry rescued a group of British sailors who were stranded aboard a steamer called the Panama. The Brits weren’t clinging to rocks as waves crashed around them and sharks circled, or anything melodramatic like that, but Turner welcomed the hapless crew aboard the wind-powered Lewis Perry, which didn’t need so much as a puff of steam to get them to a safe port. This act of high-seas gallantry resulted in a personal thank-you gift (a telescope) from Queen Victoria herself.

“Instead of a cargo hold able to carry 100 tons of Hawaiian sugar to San Francisco—the specific task for which many Turner Shipyards vessels were originally built—the Matthew Turner features 38 bunks for students and crew.”

An upgrade in 1860 to an even larger brigantine called the Timandra allowed Turner and his crew to sail to, among other places, the Sea of Okhotsk off the coast of Siberia. Turner was making a trading run there when he noticed the abundance of cod being caught by Russian fisherman. The next time he sailed the Timandra to the area, in 1863, he did so loaded with 25 tons of salt to preserve what he hoped would be a bountiful catch to bring home. In the end, Turner and his crew caught 20 tons of cod on that trip, which Turner sold at a profit in San Francisco for 15 cents a pound. The event marked the beginning of a lucrative Alaska cod fishery, which today still thrives alongside fisheries for salmon and crab.

By 1865, Turner was captaining yet another fishing schooner, the Porpoise, off the Shumagin Islands in the Gulf of Alaska (at the time, Russia still owned what would become America’s 49th state). The Shumagins were closer to San Francisco than the fishing grounds in the Sea of Okhotsk, which meant Turner was able to get his 30 tons of cod to a drying facility he’d built on Yerba Buena Island in San Francisco Bay, and thus to market, faster than his farther-flung competitors.

Since leaving the goldfields with Richard Rundle in 1853 to seek a second fortune, Turner had proven himself an adept businessman, using his skills as a sailor to entrepreneurial advantage across the Pacific. But in 1868, he traded his captain’s cap for a draftsman’s pencil when he designed his second ship, a 115-foot brigantine called the Nautilus. Custom-built for him by the E. B. Cousins Island Shipyard of Eureka, California, the Nautilus was a worthy follow-up to the George R. Roberts of 20 years earlier.

For the design of the Nautilus, Turner took inspiration from racing yachts of the mid-19th century, trading the convention of the wide-bowed cargo schooner for a sleek, narrow bow. One of the effects of this somewhat radical innovation was that the Nautilus’ displacement (the part of the hull below the waterline) was moved aft, or to the rear, which allowed the vessel to use less of its wind-generated energy to cut through the ocean. At the time, the conventional wisdom was that seagoing vessels needed a heavy, beamy bow so as not to be flipped lengthwise, bow-over-stern, by enormous ocean waves. But the Nautilus was superbly seaworthy, and Turner himself sailed the Nautilus to Tahiti to show off his new ship to his friends and business associates there, virtually upon its receipt.

The point of land above the words “Brick Yard” just below Mission Bay was probably the site of Matthew Turner’s first shipyard before he moved it to Benicia.

“The idea of a finer, narrower, bow was something that had been understood by designers of racing boats and yachts,” Olson confirms, “but it hadn’t really been applied to the commercial side of shipbuilding. Turner was the first one to run with that idea, while also improving storage capacity and increasing the ability to carry sail.” The Nautilus was sleek and stable, and best of all, it was fast. “Turner had the fastest boats around,” Olson says.

Turner was so happy with the Nautilus’ lines, and the way it sliced through whatever the Pacific Ocean hurled at it, that he replicated the ship’s basic shape in a number of vessels he designed at his new enterprise, Turner Shipyards. The shipyard’s first location was on San Francisco Bay at what used to be called Brickyard Point, which is not too far from the spot where the Golden State Warriors basketball team recently built itself a fancy new $1.4-billion-dollar arena.

By 1883, Turner had moved his growing shipyard about 40 miles north up San Francisco Bay to Benicia, where day-to-day operations were managed by Turner’s older brother, Horatio, who Matthew had personally ferried, accompanied by his brother’s wife and their two children, through the Strait of Magellan to San Francisco several decades earlier. In Benicia, Turner Shipyards cranked out schooners and sloops, brigantines and barkentines, tug boats, racing yachts, and even a few barges. His schooners brought untold tons of sugar from Hawaii, helped launch at least one major shipping line (Matson), and set speed records for ships sailing between San Francisco and Tahiti. By the end of his career in 1907, Matthew Turner had designed or built 228 watercraft, more than any other American shipbuilder working at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries.

Matthew Turner rented a room at 711 Tennessee Street in San Francisco from his former gold-mining partner Richard Rundle. When Rundle died, Turner married his widow, Ashbeline, and assumed responsibility for the couple’s three young children. This photo of the Turner family is circa 1880s. Courtesy Hunt Family.

Alan Olson’s ambitions lay elsewhere, and reflect his coming of age in the second half of the 20th century. He used his skills as a sailor to educate kids and adults alike about sailing and the sea. On shore, his lifelong process of awakening that began with the Excitandum in 1962 included stints at a Northern California Buddhist retreat called Odiyan, where, between the late 1980s and 2002, Olson spent five years, on and off, living and working as part of an all-volunteer crew tasked with building the monastery’s impressive temples. This landlocked experience, Olson says, helped prepare him for the Matthew Turner project at Call of the Sea.

“We were in way over our heads,” Olson says of his work at Odiyan. But that feeling of being at sea, so to speak, proved helpful when it came time to tackle a 132-foot-long brigantine. “I learned how to approach something I hadn’t done before,” he says, “how to get the knowledge you need to get started, how to assess if things are going right as the project proceeds, and how to work as a volunteer with a team of other volunteers.”

All of those lessons have been directly applicable to the Matthew Turner project. “That was good schooling,” Olson says of Odiyan. “Without that experience, I don’t know if I would’ve felt confident enough to take this on. But I had built temples, so why not a boat?” For Olson, his time at Odiyan made the prospect of raising the almost $7-million dollars needed to build the Matthew Turner, and then managing every detail of its construction, a little bit less daunting.

Before he passed in 2014, Matthew Turner family historian Murray Chapman Hunt (left) got to know Alan Olson, who’s in charge of the brigantine named after Hunt’s great-grandfather. Courtesy Hunt Family.

As a well-read sailor, Alan Olson knew all about Matthew Turner before the idea of building a 132-foot brigantine named after the great shipbuilder was a gleam in anyone’s eye. But until the Matthew Turner project at Call of the Sea began to take shape, Olson had never met any heirs of Turner’s extended family. That changed relatively early in the project when Olson was introduced to Eileen Hunt, her sister Claudia Hunt Putnam, and their father, Murray Chapman Hunt, who was the keeper of the Turner family archives until he passed away in 2014. This connection between Olson and the Hunts instantly transformed an ambitious education-and-shipbuilding project into a family affair. “When our Dad showed up at the construction site,” Claudia says, “Alan would just part the seas of his busy schedule to hang with him. They were kindred spirits for certain, and became very fond of each other.”

Even before his personal connection with the Hunts, Olson had been very keen to make sure the ship he was building in the present was doing justice to the past. To that end, Olson and Call of the Sea worked with Andy Davis of Tri Coastal Marine to customize the design of a famous 1891 Turner Shipyards brigantine called the Galilee to suit the needs of a classroom at sea. For example, instead of a cargo hold able to carry 100 tons of Hawaiian sugar to San Francisco—the specific task for which many Turner Shipyards vessels were originally built—the Matthew Turner features 38 bunks for students and crew.

Sisters Eileen Hunt (left) and Claudia Hunt Putnam are the current keepers of the Matthew Turner family archives. Photo by John Riise, courtesy Call of the Sea.

In some cases, 19th-century shipbuilding techniques were chosen for the 21st-century ship, such as the decision to build the hull out of Douglas fir using a traditional technique known as carvel planking. “The material, the Douglas fir, is the same as it was in Turner’s time,” Olson says, “and we steamed each one of the planks to bend it into shape, so that was basically the same technique, too.” Some of the ship’s timbers, though, are not timbers at all but laminated composites made up of countless smaller pieces of wood that have been glued together. “Laminated materials are stronger and allow a lot more shapes,” Olson says. Similarly, while the design of the rigging is traditional—square sails on the front or foremost mast, gaff sails on the mainmast—the sails themselves are made of Dacron, a durable manufactured fabric made from polyester fibers, which obviously did not exist in the 19th century.

The most cutting edge of the Matthew Turner’s 21st-century technologies is its regenerative electric propulsion system, which stores the energy generated by the natural rotation of the ship’s propellers as they move through the water in a bank of batteries, enabling the Matthew Turner to stay on course even if it finds itself in the doldrums.

Ironically, if Matthew Turner had wanted to be as cutting edge back in the 19th century as Alan Olson is in 21st, he would have focused his energies on coal-fired steamships, which were the vessels of choice for shipbuilders on the Great Lakes, along the Eastern Seaboard, and throughout the Gulf of Mexico. Instead, Turner Shipyards built scores of wind-powered sailing ships, all those aforementioned schooners, sloops, and brigs. That’s because coal-fired steamships weren’t conducive to covering the enormous distances between ports on the Pacific—you might be able to carry enough coal to get yourself from San Francisco to Hawaii, but not enough to get back. Besides, unlike his counterparts to the east, Turner and his customers in California were far from steady supplies of cheap coal, so coal-fired steam technology was then an expensive alternative to free wind.

The trim of the Matthew Turner’s 11 sails is controlled by almost 100 lines. At right is the bank of batteries that will store energy generated as the ship’s propellers turn in the water while under sail. Courtesy Call of the Sea.

How expensive? Well, by 1870, as Turner Shipyards was beginning to ramp up production, the handful of small coal mines that had tried to make a go of it just east of San Francisco had already gone out of business, managing to produce only a few thousand tons of sub-bituminous coal, the type of the mineral most suitable for generating steam. Steadier supplies of coal could be shipped from the Pacific Northwest, where it sold for $11 a ton, but by the time that coal reached San Francisco, the price almost tripled to $28 a ton.

Turner’s customers weren’t anxious to pay premiums like that, so instead of pushing coal-fired steam technology, Turner pushed wind, narrowing the bows of his schooners so they’d slice through ocean waves, but also rigging the square and gaff sails on his brigantines so that a captain could respond quickly to a sudden gale or make the most of a dying breeze. By pushing wind, Turner not only helped the new oceangoing sugar and cargo industries that sailed his ships achieve profitability, he set a high standard for sailing vessels at a time when they were actually going out of style.

A view up into the rigging of the Matthew Turner being built by Call of the Sea.

This legacy permeates every plank of the Matthew Turner, which promises to deliver a rich learning experience to the budding sailors who step aboard. But while the principles of seamanship are important to Olson—understanding how sails form pressure gradients to move a vessel; learning to steer; tying a proper knot—he’s more interested in the bigger lessons that come from being out on the water, where one is subjected to the forces of often unforgiving elements.

“The first goal is to get the students physically in touch with nature,” Olson says. “That’s what sailing is all about. You have to hold onto the lines; you can’t just let go. It’s not a game. Most everything kids do today is a game, looking into a screen. Being on a ship is nothing like that. This is immediate involvement with nature, with real consequences. What they do matters, and so they have to work as a team. They have to trust each other. That’s powerful stuff. We have a saying—ship, shipmate, and self. That’s the order of things.”

Matthew Turner would have probably added one more item to that list: family. Indeed, Turner took his promise to Rundle’s family, which he embraced as his own, very seriously. He saw to it that the Rundle children, George, Charlotte, and Eva, were given proper educations. When George was old enough, he was given a job in the shipyard as a carpenter. When Charlotte and Eva married, their husbands, Charlie Chapman and Nelson Andrews, were hired at the shipyard as well. When the shipyard moved to Benicia in 1883, Ashbeline’s children and grandchildren moved there, too. Matthew and Ashbeline Turner, though, remained in San Francisco, where they lived until 1903 before moving to Berkeley.

Little Eva (center), the granddaughter of Matthew Turner, spent a lot of time at the Turner Shipyards, pictured above. Her father, Charlie Chapman (right), ran the shipyard from 1897 until 1906. Courtesy Hunt Family.

One of Charlotte’s children was Eva Turner Chapman (1889-1986), who is the mother of family historian Murray Chapman Hunt and was called Little Eva to differentiate her from her aunt, Big Eva. Murray Hunt’s self-published family history contains numerous typed and handwritten letters to Little Eva from her doting step-grandfather. In one letter dated December 8, 1890, and addressed to “Baby Chapman” (we can assume Little Eva’s parents read this letter to their toddler), Turner writes that he has “received a communication from Santa Claus,” and “reports of your conduct are good.” A doll is mentioned as just one of several possible Christmas gifts.

Other letters are addressed to “Eva The Little,” a salutation Little Eva apparently loved even at the age of 88, when, in 1977, she was interviewed about her step-grandfather. In that interview, which is also reprinted in Hunt’s history of Matthew Turner, Eva describes growing up around the Benicia shipyard, from the way the cabins that were removed from old ships were repurposed as play spaces for the shipyard kids, to the lack of plumbing in the privies, which Eva remembers as emptying directly into the bay.

When Little Eva moved to San Francisco to attend elementary school, she lived with her grandparents, which is how she got so close to Matthew Turner. In particular, Eva cherished the times they’d crawl into bed together so he could read to her. “He read Kipling, Alice in Wonderland, and many animal books,” Eva told her interviewers. “We had a close relationship. This was a whole different activity than building ships, and he loved it. He could come down to my level.”

Little Eva at age 5 in 1894 and age 84 in 1973. She lived to be 97. Courtesy Hunt Family.

Turner had loved Little Eva from the day she was born. To mark that blessed event, Turner named a schooner after her. When she was 13, in 1902, Turner asked Eva to christen a second Matthew Turner, which, like the first one that launched in 1877, was also a schooner (that makes Call of the Sea’s Matthew Turner at least the third vessel to bear the shipbuilder’s name).

Just as Little Eva had a special relationship with her grandfather, Matthew Turner, Claudia and Eileen had a special relationship with their grandmother, Little Eva. “My grandmother lived in San Francisco, Berkeley, and Stockton,” Claudia says, “before retiring up in the Santa Cruz Mountains. When Eileen and I were 5, our parents bought a house in Menlo Park, California, but we would spend summers up in the Santa Cruz Mountains, staying in a little cabin across the street from my grandmother’s house. There was no phone, no music, no TV up there. It was just visiting grandma and hanging out, playing in the redwoods, going down to the river, exploring.

“She was a very fine lady,” Claudia continues, “classy, but down-to-earth. And she had all kinds of mementos from Matthew Turner’s life because she had lived with him and her grandmother during some of her most formative years. She loved her step-grandfather, absolutely adored him. I never heard anything about her grandmother, Ashbeline. All I heard about was Matthew Turner, about how he’d tuck her in at night and read her stories. I wouldn’t be surprised if she read Eileen and I some of the same books that he used to read to her.”

The new Matthew Turner being built by Call of the Sea takes much of its design from another Turner Shipyards brigantine, the Galilee, seen here in 1907 near Sitka, Alaska. Courtesy Hunt Family.

Today, educators know how important it is to read to children, but Turner was likely acting on dead reckoning, to use an ocean-navigation term, to determine how best to mold and improve the mind of his granddaughter. To that end, Turner included Little Eva in activities that would serve her well as an adult. “When she got a little older,” Claudia says, “he used to let her do the payroll on payday, handing out gold and silver coins to all the workers. And I’m sure he put her through a very fine ladies finishing school in San Francisco. She was very proper,” Claudia says. “Even up in the Santa Cruz Mountains, just going to the grocery store, my grandma wore white gloves.”

The Matthew Turner shares this sense of refinement. As a work of naval architecture, the ship is polished and beautiful, from its sleek lines to the gleam on the brightwork. But the Matthew Turner is also tough, ensuring that it won’t splinter into so many tons of Douglas fir toothpicks after repeatedly crashing into wave after ocean wave.

“We’re building something that will go on well beyond our own lives,” Olson says of the work he’s doing with his fellow volunteers at Call of the Sea. “We look at the Matthew Turner as lasting for a hundred years or more, serving generations of kids, grandkids, and even great-great-grandkids.”

400 Years of Equator Hazings: Surviving the Stinky Wrath of King Neptune's Court

400 Years of Equator Hazings: Surviving the Stinky Wrath of King Neptune's Court

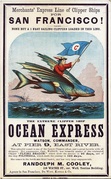

Extreme Shipping: When Express Delivery to California Meant 100 Grueling Days at Sea

Extreme Shipping: When Express Delivery to California Meant 100 Grueling Days at Sea 400 Years of Equator Hazings: Surviving the Stinky Wrath of King Neptune's Court

400 Years of Equator Hazings: Surviving the Stinky Wrath of King Neptune's Court From Whale Jaws to Corsets: How Sailors' Love Tokens Got Into Women's Underwear

From Whale Jaws to Corsets: How Sailors' Love Tokens Got Into Women's Underwear Ships ClocksDuring the 19th century, the British Empire covered about 10,000,000 square…

Ships ClocksDuring the 19th century, the British Empire covered about 10,000,000 square… Model Ships and BoatsModels of ancient wooden boats have been found in tombs across the Mediterr…

Model Ships and BoatsModels of ancient wooden boats have been found in tombs across the Mediterr… Ship Lanterns and LampsSome of the earliest ship lamps burned whale oil, either refined from the b…

Ship Lanterns and LampsSome of the earliest ship lamps burned whale oil, either refined from the b… Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

I am very proud and and thankful that I have had the privilege of helping build the Matthew Turner. To be able to see the ship being built from the beginning to the end is a gift like no other. All of us who have volunteered have had a life experience that will stay with us the reminder of our lives. A deep feeling of thanks to Alan for his dedication and willingness to take on a project like this is amazing.

THANK YOU !!!!!!!

What a wonderful story! Thank you for sharing.

Many thanks to my nephew, Gerard Rochefort (Chapman) son of Taimandra Rochefort Chapman for all this knowledge. Being a descendant of Benjamin Franklin Chapman’s Tahitian family I never knew of this other lineage.Glad to know now.

Truly an inspiring and heartful account of one’s dreams and perseverance thru hardship. Thank you for sharing this.

Very nice … my great grandfather was a ships captain up in Nova Scotia he went after a different kind of gold …dark rum …he would sail over to county of Cork Ireland where he was born pick up a load of rum and sail back to Nova Scotia where they would pump it off the ship to barrels buried on the shore line ,no fly’s on him … his name was capt Walter Murphy of Nova Scotia,

Thanks for the story, very nice read.

My maternal grandfather, Joseph Cleveland Pearson, served in the ‘Galilee’ during the magnetic expeditions as a field observer employed by the Carnegie Institution. He was aboard the ship when she visited Sitka, Alaska, as shown in one of the photos in this article. I am developing a set of construction plans for ‘Galilee’ as she was configured in 1908. From all accounts, Captain Turner was a principled, kind, and gifted shipbuilder.