What’s the difference between a banjo and a lawnmower? You can tune a lawnmower. What’s the difference between a dead skunk in the middle of a road and a dead banjo player in the middle of a road? There are skid marks in front of the skunk. Speaking of which, how many banjo players does it take to eat a possum? Two, one to eat it and the other to watch for cars. And last but definitely not least, what do you call 100 banjos at the bottom of the ocean? A good start.

“The banjo in postwar America was perceived primarily as a white, rural instrument.”

There are entire websites devoted to banjo jokes, so we could spend all day on this, but let’s not. Instead, hang on to those descriptions of unplayable instruments and moronic musicians eating roadkill. Though they may produce casual chuckles today, these jokes are actually rooted in the racist put-downs that were once directed at Black banjo players in America, as we learned when we spoke recently to Laurent Dubois, whose new book, The Banjo: America’s African Instrument, was published in the spring of 2016 by Harvard University Press.

Dubois’s book arrives at a weirdly bipolar moment in Western cultural history. On the one hand, the five-string banjo has never been more popular. Winston Marshall of Mumford & Sons plays sold out concerts with a top-of-the-line Deering banjo strapped over his shoulder, as does Scott Avett of the Avett Brothers. On Broadway, “Bright Star,” which was co-written by the funniest banjo player alive, Steve Martin, enjoyed a spirited, if brief, run. And even pop idol Taylor Swift has woven the sound of the banjo (albeit a six-string variant that’s tuned like a guitar) into her multi-platinum repertoire.

Top: “The Banjo Player,” 1856, by William Sidney Mount. Via Wikimedia. Above: “The Old Plantation,” 1785-1790, depicts life on a South Carolina plantation. From the collection of the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Museum, Colonial Williamsburg, Virginia. Courtesy SlaveryImages.org, a project of the Virginia Foundation for the Humanities.

At the same time, racism in the United States hasn’t been so naked in decades. Young African American men are routinely gunned down by peace officers, prompting everything from the #blacklivesmatter movement to the refusal of an African American quarterback in the NFL to stand at attention during the national anthem. For many, the presidential election in the United States is itself a referendum on racism, particularly as it applies to which religious groups should be allowed inside the nation’s borders, and whether portions of those borders should be visible from space after the construction of a massive wall.

What, you might ask, does racism have to do with the banjo, an instrument that for most people is no more controversial than the banjo-heavy theme song for “The Beverly Hillbillies”? Well, race is actually central to any conversation about banjos, or at least it should be. That’s what makes The Banjo so relevant in 2016. The book includes a detailed explication of the instrument’s African origins before the slave trade, its Caribbean evolution in the 16th to 18th centuries, and its racist reinvention in 19th-century America. After reading Dubois’s book, this old-timey instrument may never sound the same to you again.

“The roots of the banjo,” Dubois begins when we spoke over the phone recently, “are not found in one specific instrument from a particular place in Africa. Instead, the banjo is pan-African.” For example, to this day, the Hausa people of West Africa still play a number of instruments that could be considered predecessors of what we know in the West as the banjo. Among these are the kuntingo, which has just one camel-hair string, a bamboo neck, and a resonator covered in calfskin. There’s also the babbar garaya, which features two strings and a body fashioned from a halved gourd. An even more direct ancestor is the akonting, which is still played by the Jola people of Gambia and was first documented for Westerners by an 18th-century Scottish explorer named Mungo Park. The akonting not only has a gourd covered with an animal skin, but it also has a bridge for the instrument’s three strings. And just like on modern-day banjos, the shorter top, or bass, string is played with the thumb.

While the akonting is usually singled out as being the closest African instrument to the modern American banjo, all of the instrument’s pan-African predecessors share one key trait—an animal skin stretched over the top, or head, of the resonator, not unlike the heads on drums and tambourines. The backs, sides, and tops of lutes, violins, and other chordophones (the term for stringed instruments ranging from acoustic guitars to zithers) are always made of hard substances, usually wood or steel, but the heads of banjos are fashioned from pliable materials. In Africa, that material was typically animal hide, often goat or antelope.

“The only thing that connects this instrument across space and time is the drumhead,” Dubois says. Today, banjo heads are made out of a plastic called Mylar, a Mylar hybrid called FiberSkyn, or high-strength Kevlar, which the Deering Banjos website describes as having “a surface texture like an orange peel.” Presumably, the phrase “a surface texture like a freshly flattened possum” might have been just as accurate, but it probably wouldn’t have struck very many banjo players as funny.

There was also nothing funny about the instrument’s arrival in the New World. Actually, the banjo itself never left Africa, but memories of banjo-like instruments did. Those memories, alas, were no doubt among the few pleasant thoughts in the minds of the human beings who, beginning in the 16th century, were wrenched from their homes in West and Central Africa and sold into slavery. From what are now Senegal in the north to Angola in the south, regardless of their ethnic affiliation or language, these human beings were packed into ships like sardines for the Atlantic crossing to Brazil and numerous Caribbean nations, including what are now Haiti and Jamaica.

A page from Hans Sloane’s A Voyage to the Islands of Madera Barbados, Nieves, S. Christophers and Jamaica, 1707. This image was taken from a copy of the book in the John Carter Brown Library at Brown University. Courtesy SlaveryImages.org, a project of the Virginia Foundation for the Humanities.

Once in the New World, enslaved people who survived the voyage—the mortality rate for slaves shackled together in the holds of slave ships ranged from 10 to 25 percent per trip—were forced to grow, harvest, and mill cane, which was then shipped back across the Atlantic as sugar, to satisfy Europe’s growing appetite for sweets. Slave-worked tobacco and cotton plantations in the southeastern United States followed, in the 17th and 18th centuries respectively, spurring international commodity markets centuries before anyone had coined the word “globalization.”

Not surprisingly, it mattered little to a plantation owner in Haiti whether his slaves were Hausa, Jola, or whoever. On New World plantations, a back was a back and a pair of hands were a pair of hands, tools to be worked to death if necessary. Indeed, a centerpiece of this systematic dehumanization was to ignore an individual slave’s unique roots, which is actually how the one-size-fits-all concept of generic “African” identify first took hold in the West. People had family histories and homelands—property did not.

Eventually, all those memories of banjo-like instruments in the minds of all those Hausas, Jolas, and whoevers coalesced into banzas, banjas, banjers, banjous, and bangiers, as just a few of the various New World incarnations of banjos were called. At some point, “banjo” became the word used to describe an instrument played by people called “Africans,” each term at once defining its object and stripping it of its deeper, more nuanced meaning.

Replica by Pete Ross of the banjo in the painting called “The Old Plantation” shown above. Via Pete Ross Custom Banjos.

In relatively short order, the gourd banjo bodies, or resonators, that had been so common in West Africa were replaced with gourd-like calabashes, which grew in abundance in the New World. Similarly, with no ready supply of camel or elephant hair for strings, New World banjo makers—which for hundreds of years meant enslaved people—turned to horse hair or tough, stringy plants such as vines. With musical raw materials just as common in the New World as they had been in West Africa, plantations throughout the Americas were soon humming with the sounds of the old country.

“Almost everybody on New World plantations would’ve remembered the sound of some kind of instrument with a resonator,” Dubois says. “The rest of the instrument might have been different, but the basic sound would have been familiar.” To hear what these instruments could have sounded like, Dubois and a couple of colleagues have created a site called Musical Passage, which features music that they perform based on transcriptions recorded by an Englishman named Hans Sloane, who visited what is now Jamaica for 18 months during 1687 and 1688.

According the Dubois, this auditory uniformity served both musicians and audiences well. “If you were a slave in Haiti,” he says, “and you played an instrument whose music was only familiar to one group of people but unfamiliar to another, as a musician, you’d basically be signaling that you were only playing for that first group.” The plantation dynamic, Dubois says, “created an interesting demand—to play music that crossed boundaries so that it appealed to people from different parts of Africa.” It was in this context that instruments such as the kuntingo, babbar garaya, and akonting, became the banza, banjer, and, eventually, the banjo.

A contemporary gourd banjo by Pete Ross, based on traditional designs used by the Mande people of West Africa. Via Pete Ross Custom Banjos.

Like the banjo itself, there are African antecedents for the slaves who played them. Foremost among these musical forebears is the class of professional musicians called griots (pronounced “gree-ohs”), who are still revered in parts of West Africa today. Though it’s unclear to Dubois exactly how far back the griots go, they are first referenced in African literature in the Sundiata Epic of 14th century Mali. In that tale, a griot named Balla Fasseke helps the epic’s hero, Sundiata Keita, become Mali’s king. Beyond that plot point, the epic specifies that griots were the “depositories of the knowledge of the past,” which they perpetuated via music and song.

“The griots,” Dubois writes in The Banjo, “became not only the players of these instruments but also their makers… In particular, a group of instruments with an oblong wooden body covered with an animal skin resonator—and known variously as the xalam, ngoni, or huddu (among other names)—were familiar in many different regions.” When played by the griots, Dubois writes, “these instruments were celebrated and understood as vital participants in the transmission of memory and history,” making them, “powerful symbols, condensing history and lineage, their sound connecting the living to generations of their ancestors.”

Accordingly, the griots and their heirs, who also became griots, were given great privileges by West African kings, even permitted, as described in the Sundiata Epic, to “make jokes about all the tribes, and in particular the royal tribe of Keita.”

“They are kind of like court jesters,” Dubois tells me, “but it is a more dignified status than that because they are also the keepers of the memory of the kingdom. They’re the ones who can recount from memory the royal family genealogies, as well as the roots of their own families, going back hundreds and hundreds of years.”

A replica by Pete Ross of the “Haiti Banza.” The original has been in the collection of the Musee de la Musique, Paris, since 1840. Via Pete Ross Custom Banjos.

Just as importantly, if not more so for the enslaved musicians that followed them, griots help their societies look forward. “They can inspire the future,” Dubois says, “in the sense that they use the past to help a particular king or army or group figure out what to do today. We had a modern-day griot come to Duke University, where I teach,” Dubois adds, “and he emphasized that they think of themselves as peacemakers, as people who can negotiate between different social groups or even amid political conflicts inasmuch as knowledge of the past can help people deal with the present. So, in some ways, the role the griots play condenses the role musicians often play in societies, although in the griot case, it’s much more formalized because it’s hereditary.”

On the Caribbean plantations of the 17th and 18th centuries, such past-to-future perspectives were crucial to the social structure of the enslaved. “Because the experience of plantation slaves in the Caribbean and elsewhere was so extreme,” Dubois says, “it’s not surprising that it produced musicians who were adept at playing this very unique role.”

As the primary instrument of plantation musicians, the banjo became a symbol of transformation and transition—be it the journey from Africa to the New World, or passage from pain and suffering in the present to relief and redemption in the hereafter. Indeed, one of the occasions when a banjo would just about always be heard was the funeral. In particular, in the Haiti of the late 18th and early 19th centuries, the sounds produced by musicians playing banjos were thought to have healing powers. For example, one banjo Dubois came across in his preparation for his book is a Haitian banjo with three leaves carved on its wide neck, a reference, perhaps, to an 18th-century Haitian musician named Trois-Feuilles. More broadly, Dubois writes, the carving may have been meant to confirm “the role of herbal knowledge within the system of physical and spiritual healing that is Haitian Vodou.”

A Pete Rose re-creation of the banjo shown in Hans Sloane’s A Voyage to the Islands of Madera Barbados, Nieves, S. Christophers and Jamaica from 1707. Via Pete Ross Custom Banjos.

“For me, that is heart of the book,” Dubois says. “I’ve studied Haiti for years, but this is an aspect of Haitian culture and history that hadn’t been done before. It took a lot of steps to figure out that it wasn’t just a random symbol but possibly a connection to this idea in Haitian Vodou about leaves, three leaves in particular, which are a symbol for herbal knowledge and healing. It’s a link back to Africa—so much of Haitian Vodou is an articulation of how even in exile you can reconstitute Africa and connect back to it. In many of the ceremonial aspects of Vodou, one actually calls on spirits, who represent a connection to Africa. When called, they will return to spend time with their children or descendants, transported from one continent to another via the spiritual realm. Admittedly, Haitian Vodou is almost certainly not the first thing people in America today think about when they hear the word ‘banjo,’ but once I established this possible connection, it just made so much sense that music, which is almost universally seen as healing, via the banjo, would’ve been used to impart this spiritual practice.”

“As the primary instrument of plantation musicians, the banjo became a symbol of transformation and transition.”

Naturally, this sort of thing made a lot of white slaveholders of European descent nervous, although they were not always of one mind when it came to what to do about the music being produced by their human property. Some simply did not permit music on their plantations at all, and the banjo was often banned, lest it be used to communicate coded acts of rebellion and spur uprisings on plantations, activities that were even more worrisome to slaveholders than something as nebulous as sonic Vodou. Other slaveholders, though, took advantage of the talent of their slaves, compelling musicians on their plantations to perform for guests at their parties, sometimes even inviting musicians of color into their white homes on special occasions. For these slaveholders, race and class were less important than good music—for a few moments, anyway.

Which is not to say that slaveholders who appreciated the musical skills of their slaves were enlightened precursors to Abraham Lincoln. In fact, Dubois’s book contains numerous references to newspaper advertisements written by slaveholders searching for their runaway slaves. In addition to the usual list of distinguishing characteristics—age, height, weight, scars—these slaveholders would also highlight the ability of their slaves to play instruments such as fiddles and banjos. As a result, runaways ran the risk of being caught in the act of playing music, which happened to be one of the few ways for people of color to earn money away from the plantation. For runaway slaves, music could be a trap.

Illustration of “A Carolina rice planter” from “Harper’s New Monthly Magazine,” 1859. Image taken from a copy of the magazine in the Special Collections Department of the University of Virginia Library. Courtesy SlaveryImages.org, a project of the Virginia Foundation for the Humanities.

Tellingly, slaveholders were so desperate to reclaim their human property, they even mustered a tactical interest in their runaways’ tribal ethnicity. As Dubois describes it in The Banjo, during the late 18th and early 19th centuries, slaveholder advertisements in a Haitian newspaper called “Les Affiches Americaines” included the names of more than 200 African ethnic groups, alongside the references to height, weight, and scars. As with the ability to play a banjo, a slave’s ethnicity was often the difference between his freedom or capture. Ironically, these runaways would have been better off cloaked in the dehumanized anonymity of being generically “African.”

If slaveholders were not of one mind when it came to the presence of banjos and music on their plantations, early ethnographers were just as confused, although their perspectives generally corresponded to their view of slavery, which by the 18th century was finally being questioned in the form of abolitionist movements in Europe and slave revolts in the Caribbean. Apologists for slavery saw the sounds of banjos and bones—percussive sticks that were clacked together to provide a rhythm for a song—as evidence that the enslaved were actually happy. If slaves were really so miserable and resentful of their lot in life, this tin-eared argument went, why do they sing and dance so much? But abolitionist observers, noting the enormous effort required to play music into the wee hours after an exhausting day in the fields, saw music as evidence of the value enslaved people placed on those precious moments when they could finally do as they pleased. For many, hearing the sound of a banjo was literally more important than getting a good night’s sleep.

By the beginning of the 19th century, that sound had become increasingly familiar to the white residents of the Southern United States, but not because the sweet melodies of late-night slave hootenannies were wafting across dew-dappled cotton fields and into their humble homes. Rather, in 1808, when the Slave Trade Act of 1807 took effect, enslaved people could no longer be imported into the United States, as had been the practice for almost 200 years. That meant the 1.2 million enslaved people living in the United States, representing just under 20 percent of the population, would need to be moved around the country to meet the demands of the burgeoning cotton empire—spurred by Eli Whitney’s 1793 cotton gin—and the country’s expanding borders—the Louisiana Purchase of 1803 roughly doubled the young nation’s size.

Illustration from an 1852 copy of a critique of Uncle Tom’s Cabin by Robert Criswell. Courtesy SlaveryImages.org, a project of the Virginia Foundation for the Humanities.

In general, the migration of slaves within the United States went from east to west, and it was not a pretty sight, as recalled by a British traveler named George Featherstonhaugh, who wrote about his encounter in Virginia with a “coffle” of several hundred shackled male slaves, plus a number enslaved women and children, on their way to be auctioned to the highest bidder in Natchez, Mississippi. The men, Featherstonhaugh wrote, were “manacled and chained to each other,” while the slave traders, in their “broad-brimmed white hats,” stood nearby, “laughing and smoking cigars.” In The Banjo, Dubois quotes Featherstonhaugh’s undisguised disgust: “Black men in fetters, torn from the lands where they were born, from the ties they had formed … driven by white men, with liberty and equality in their mouths, to a distant and unhealthy country, to perish in the sugar-mills of Louisiana!”

Naturally, enslaved people would routinely try to escape their bonds in an effort to avoid such a fate. Counterintuitively, perhaps, the slave traders occasionally fought this impulse by hiring, as Featherstonhaugh writes, “Other negroes trained by the slave-dealers to drive the rest, whom they amused by lively stories, boasting of the fine warm climate they are going to, and of the oranges and sugar which are there to be had for nothing.” These Black storytellers, “urging the men to be merry,” as Dubois puts it, often accompanied themselves on the banjo. Slave traders even had Black banjo players perform during slave auctions, so much so that the table upon which a slave stood, so that would-be masters could get a good look at the merchandise, was sometimes called the “banjo table.”

If chance encounters such as these were one way whites learned about Black performers who played the African banjo, a ticket to the theater was the other. For it was in the early 1800s that minstrel shows took the country by storm, offering white audiences a rose-hued view of life on Southern plantations, performed by whites wearing blackface.

White performers pretending to be Black for white audiences? Apparently, ’twas ever thus. Indeed, according to Dubois, we in the 21st century are still living with legacies from the minstrel shows of the 19th. There are the little things, like the word “ham,” which still describes an actor who overacts, but comes from the practice of mixing ham fat with burnt cork to make the black makeup that white minstrels applied to their faces to disguise their race. Far more insidiously, the minstrel shows codified racist stereotypes about African Americans—from their “natural” sense of rhythm (less a compliment than an explanation of how uneducated musicians could possibly be so good) to their manner of speaking (the most offensive examples of Black Southern dialects were written, rehearsed, and perfected by white minstrels).

Re-creation by Jim Hartel of a banjo made by Joel Walker Sweeney in 1845. Via Hartel Banjos.

The banjo climbed onto the minstrel stage in 1839, when a white Virginia musician named Joel Walker Sweeney played his banjo in blackface at the Old Italian Opera House in New York City, providing musical interludes between the plate spinners, opera singers, and magicians. Even in the hands of Sweeney, though, the banjo was considered an African instrument. “When whites are having to dress up as Blacks in order to play the banjo,” Dubois says, “it becomes a reminder that the banjo is really a Black instrument.”

According to Dubois, Sweeney earned positive reviews from “The New York Herald Tribune,” and was so confident of his career prospects that he turned down an offer from none other than P. T. Barnum (circuses like Barnum’s were prime employers of blackface performers in those days).

Sweeney was soon “banjoizing,” as one newspaper put it, throughout New England, and by 1841, advertisements for his performances touted the “scientific touches” of his banjo playing, a not-so-subtle attempt to assure white audiences that this white musician was fully in control of the “primitive” properties of what was widely understood at the time to be an African instrument. Sweeney put action behind his marketing hype by playing a banjo that had an additional fifth string, which increased its melodic range. This, writes Dubois, led some subsequent scholars and partisans to claim that Sweeney had actually invented the banjo, which he certainly did not—in fact, he was probably not even the first American to play one with a fifth string. Still, the five-string banjo became the standard form of the instrument throughout the 19th century, in no small part due to Sweeney’s popularization, and it remains the banjo standard to this day.

Sheet music from 1843 for the Virginia Minstrels. Via Wikipedia.

Evidence of the banjo’s African roots was everywhere throughout the minstrel era, although the geographical references often strayed from the West and Central African homelands of America’s enslaved people. The Virginia Minstrels, who first performed under that name in 1843, included a piece titled “Ethiopian Serenade” in their repertoire, Ethiopia being in East Africa. Their banjo player, William Whitlock, played a four-string “Congo” banjo, which geographically speaking was at least a bit closer to the mark.

In those days, most of the banjos played by the early blackface minstrels were also African—or at least Caribbean—in their construction. These handmade, one-of-a-kind instruments generally featured gourd or calabash resonators, a fair number of which were covered with woodchuck hide. Even J. W. Sweeney played an African-style banjo. But catching woodchucks, skinning them, and then nailing their tanned hides to the sides of fragile gourds was a lot of work for a performer on tour, and something most aspiring urban banjo players were unprepared to do.

In 1837, the drum came to their rescue. That’s when a metal drumhead tensioning rod was patented. This simple device held drumheads in place better than nails or tacks. A few years later, in 1840, a Baltimore musical-instruments store owned by William. E. Boucher, Jr. began using this device to hold down the heads of the banjos it began to produce to meet the growing banjo demand. “In addition to the new method for attaching the skin,” Dubois writes in The Banjo, “the necks were elegantly carved with distinctive peg heads, usually in an ‘S’ shape.” Soon, builders were manufacturing banjos in batches rather than one at a time, cutting multiple pieces of pear, maple, mahogany, or rosewood for the necks, and patenting parts designed to make the instrument more durable and improve its tone.

Re-creation by Jim Hartel of a Boucher banjo from around 1850. Via Hartel Banjos.

Beyond the banjo’s physical reinvention, the instrument was also given a new coat of cultural paint. Its new color would be white.

The transformation of the banjo from a Black African instrument to a white American one occurred from the 1840s through the 1880s, the decades when the banjo’s popularity exploded and took hold. The motivations were equal parts racism and the chase for the almighty buck, as manufacturers such as the Dobson Brothers, and Samuel Swain Stewart, along with banjo proselytizers such as Joel Chandler Harris (author of the Uncle Remus stories) and Frank Converse, made two basic arguments. First, the gourd and calabash instruments played on plantations and minstrel stages were primitive objects, arguably not even banjos at all, at best mere prototypes for the more technologically advanced instruments made by American manufacturers. Second, slaves were too stupid to play these instruments with anything approaching virtuosity, so their contribution to the instrument’s history is just as well ignored.

One other motivation for this cultural deception was the urge to define America’s place on the world stage. “A key irony,” Dubois says of the banjo’s 19th-century revisionist history, “is that in order for Victorian America to distinguish itself from Europe, it needed a really American instrument to crow about. But the only place where you could get an American instrument was, of course, from Black culture. How they navigated that is fascinating because no one could ever really escape the truth. Still, Stewart, Dobson, and the rest of them succeeded to the extent that it’s still a surprise to many people today to learn that the banjo was originally a Black or African American instrument.”

Sheet music for the Ethiopian Serenaders from 1847. Via Old Hat Records.

The lies perpetrated about the banjo varied, but they all reinforced the proposition that the instrument’s connection with enslaved people was tenuous. In his history of the instrument, banjo maker George Dobson admitted that the banjo had African antecedents, but he also imagined that “Negro slaves, seeing and hearing their mistresses playing on the guitar, were seized by that emulative and imitative spirit characteristic of the race, and proceeded to make a guitar of their own out of a hollow gourd, with a coon-skin stretched across for a head.” Stewart, after first claiming that the banjo “was not of negro origin,” relented a few years later, explaining somewhat apologetically that “Truth has often come into the world through lowly channels.”

“You can actually track the history of how the idea of the banjo has evolved,” Dubois says of the instrument’s whitewashing. “These ideas weren’t just ‘in the air.’ Nineteenth-century boosters like Stewart worked really hard to make the banjo not African, to unhinge it from its history. We’re still living with that.”

Harris and Converse were even more full-throated in their racism. Citing the banjo’s use in blackface minstrel shows, Harris suggested that “The whole idea of its origins on the plantations was a theatrical fantasy,” as Dubois puts it in The Banjo. Converse, who made his living publishing manuals for white audiences to teach them how to play the banjo, flattered his readers by assuring them that “There were no players among the slaves capable of arousing its slumbering powers,” insisting that only “white admirers in the North” could awaken the instrument’s “inherent beauties.” Never mind that the techniques in his book were as stolen from enslaved people as the banjo itself. The banjo’s destiny, Converse wrote, need not be as “an accompaniment to the darkey song that told of the cotton fields, cane brakes, ‘possum hunts, sweet tobacco posies, or ‘Gwine to Alabama wid banjo on my knee,’ etc.”

Sheet music from 1848 for the Christy Minstrels, including “Oh! Susanna” by Stephen Foster. Courtesy of the Lester S. Levy Collection of Sheet Music, The Sheridan Libraries, The Johns Hopkins University.

That last line, of course, is a reference to the great American songwriter Stephen Foster’s “Oh! Susanna,” which he wrote in 1847, was popularized by the Christy Minstrels, and became one of the most famous works of American music. “The Black narrator of the song sings in dialect,” Dubois writes, “telling of his search for his love Susanna, whom he hopes to find in New Orleans.” But, as Dubois notes, the most likely way a Black man in the 1840s could have traveled from Alabama to New Orleans in the 1840s was as a slave, and probably manacled to others to “perish in the sugar-mills of Louisiana,” as British traveler George Featherstonhaugh had described it.

In fact, Dubois writes, Foster probably got the idea for “Oh! Susanna” from a slave ballad with similar lyrics, which was published in an abolitionist journal from 1835. Thus, Dubois writes, “Foster may have turned a song clearly sung from the perspective of a slave being forced to Louisiana into a comic story of lovelorn wandering.” Foster’s revisions made “Oh! Susanna” a hit on the minstrel stage, where it was frequently performed, making it one of the most famous examples of how the connection between banjos and enslaved people was downplayed, if not outright disregarded.

By the late 1880s, though, with legal slavery fully replaced by racist Jim Crow laws, Africans Americans were slowly reclaiming the banjo as their own. One of their first steps was to apply blackface to their dark complexions and pretend to be white men pretending to be Black men in the still popular minstrel shows. According to Dubois, this “Black minstrelsy,” as it’s known, was the first opportunity for all but a handful of African Americans to take the stage as professional performers. “This tradition,” he writes, “created a foundation for the performance practices of the twentieth, and even twenty-first, centuries.”

“The Banjo Lesson,” circa 1893, by Mary Cassatt. Via the National Gallery of Art. Gift of Mrs. Jane C. Carey as an addition to the Addie Burr Clark Memorial Collection.

Fortunately, Black minstrelsy was not the only banjo tradition for African Americans to look back upon. At the turn of the century, hundreds of African American musicians like Horace Weston and Ike Simonds were also playing banjos as themselves, without having to resort to redundant and degrading makeup. Others performed in circuses or in all-Black musical groups and ensembles, including with the Fisk Jubilee Singers, ex-slaves all, who performed religious numbers and songs about their families and friends on the plantation—pointedly, these numbers excluded references to their former masters.

Encouraged by this revival in Black string-band music, as the 20th century dawned, a number of prominent African Americans intellectuals made it their mission to draw attention to the corrosiveness of the minstrelsy legacy. They knew that as long as caricatures and stereotypes of African Americans were being perpetuated onstage, African Americans would struggle to get ahead in real life. Foremost among this group was W. E. B. Du Bois (no relation to Laurent Dubois, in case you’re wondering), the first African American to earn a doctorate from Harvard, among other milestones.

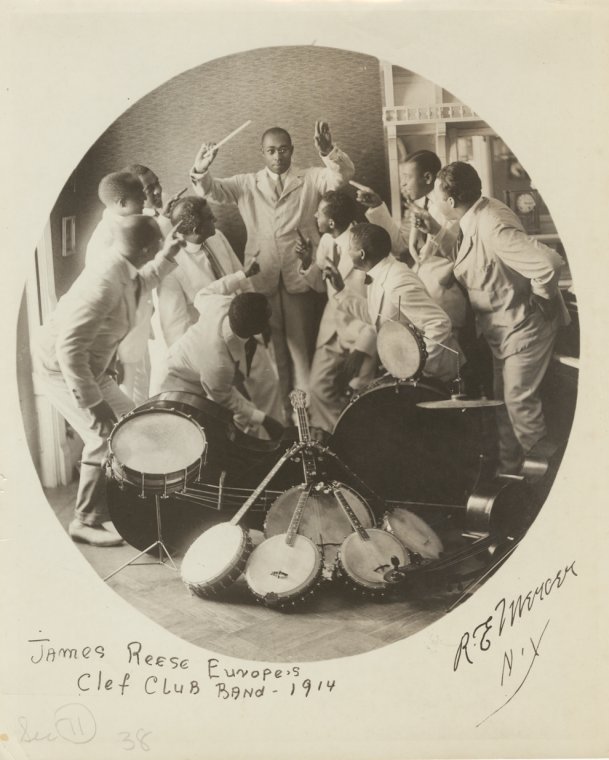

Du Bois’s musical champion arrived in 1910 in the form of James Reese Europe, who had studied music under John Philip Sousa in Washington, D.C. before moving to New York, where he founded the Clef Club. Initially, the goal of this all-African American organization was to improve wages and performing opportunities for African American musicians, but the Clef Club is best remembered for the band and orchestra that bore its name.

James Reese Europe and the Clef Club Band, 1914. Photograph by R.E. Mercer. Courtesy Digital Collections, The New York Public Library.

Drawing as it did from the available pool of African American talent, Europe’s 125-member orchestra was dominated by banjos, mandolins, and guitars, as well as 10 upright pianos. By 1912, the Clef Club Orchestra was so acclaimed, it was invited to play Carnegie Hall, where Europe’s musicians performed before a mixed-race audience—both events being highly unusual at the time. The performance was so well received that by 1913, the 50th anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation, Europe’s orchestra was touring the eastern United States, and always playing to racially mixed audiences, except in the former capital of the Confederacy, Richmond, Virginia, where seating segregation prevailed.

In 1919, Europe was stabbed to death by one of his drummers in a dispute, but the Clef Club Orchestra had established a sound that would outlive the visionary bandleader, namely, a rhythm section propelled by the strumming of the old banjo. This, in turn, spawned New Orleans Dixieland jazz. Indeed, as early as 1915, the banjo was so intertwined with the nascent New Orleans jazz scene that the sheet music for pianist Jelly Roll Morton’s “Jelly Roll Blues” featured a banjoist on its cover. By 1918, a banjo player named Johnny St. Cyr was playing alongside Louis Armstrong on a New Orleans riverboat, and St. Cyr would become a fixture in New Orleans clubs and on early New Orleans jazz records, the most prized of which featured Armstrong on trumpet.

In 1915, the sheet music for pianist Jelly Roll Morton’s “The Jelly Roll Blues” featured a banjo player on its cover.

Throughout the 1920s, no self-respecting bandleader would fail to employ a banjo player. In fact, one of Duke Ellington’s first bands, the Washingtonians, was founded by a banjo player named Elmer Snowden. When Ellington took over, he hired Fred Guy as Snowden’s replacement—Guy played with the Washingtonians until World War II.

In the end, though, the 1920s would prove a bad decade for the banjo, thanks in no small part to the invention of the microphone in 1927. Many African American musicians had already been moving away from the uniformly loud and metallic-sound of the banjo in favor of the softer and warmer tones of the guitar, which made it better suited to a rising genre known as the blues. Microphones allowed these quieter compositions to be heard by audiences. Then, in the 1930s, guitar makers such as C. F. Martin introduced a number of new lines of larger, louder guitars, which made the instrument an even more versatile. By World War II, Dubois writes, banjo sales were crashing, while untold numbers of Gibson, Fairbanks, Vega, Bacon & Day, and Paramount banjos were either tossed onto scrap heaps to help the war effort or left to languish in pawnshops.

In the 1940s and ’50s, Pete Seeger’s love for the banjo helped start the modern folk-music revival. Via Wikipedia.

That’s where a teenage Pete Seeger got his first banjo, a four-string tenor model, in 1932. A few years later, he bought his second banjo, a five-string Stewart, in a different pawnshop for just five bucks. By 1948, the Caucasian Yankee had learned so many banjo songs from so many corners of America, including the future Civil Rights anthem “We Shall Overcome,” that he was able to write the definitive manual on the instrument, How to Play the 5-String Banjo. Seeger’s winning stage persona and invaluable book were a one-two punch, igniting a folk-inspired banjo revival that was embraced by a new generation of mostly white musicians in the mid-1950s.

Meanwhile, in 1945, a North Carolina banjo player named Earl Scruggs had joined a Kentucky mandolin player named Bill Monroe in his highly influential band, the Blue Grass Boys, from which the lightning-fast, percussive style of playing gets its name. Within a few years, Scruggs and Monroe’s guitarist, Lester Flatt, had formed their own bluegrass band, the Foggy Mountain Boys. In The Banjo, Dubois recounts a story told by Seeger’s brother, Mike, about how the brothers and their banjo-playing friends would gather at Pete’s house to try and figure out just how Scruggs did it. By 1955, Seeger had enough intelligence on Scruggs’s three-finger picking style that he added a short chapter to How to Play the 5-String Banjo about the “Scruggs-style banjo.”

A Flatt and Scruggs album from 1960. Earl Scruggs played the banjo so fast, it was tough for even Pete Seeger to figure out his technique.

Countless bluegrass bands followed, including the Clinch Mountain Boys, the Lonesome Pine Fiddlers, and the Osborne Brothers, to name but a very few. Before long, the banjo in postwar America was perceived primarily as a white, rural instrument, whose bright, aggressive sound, Dubois writes, signaled the presence of “a backward, primitive, and frightening white southern culture.” This menacing side of the banjo, which is no doubt not what Pete Seeger had in mind, is exemplified in the 1972 film “Deliverance,” which featured the famous “Dueling Banjos” duet between a hillbilly boy and a businessman, who share nothing in common except a love for the language of the banjo and the velocity of its notes.

But if the banjo was perceived by many as a white instrument by the mid-20th century, it still had its African American virtuosos, even if most of them would go through life without acclaim. The great singer, songwriter, and instrumentalist Taj Mahal was influenced by at least two such anonymous figures. “One of my earliest encounters with the banjo was when I was 9 or 10 years old,” Mahal told me when we spoke on the phone the other day. “Me and an old guy from West Virginia or Kentucky used to look after a veterinarian’s place. After the vet would go home, he would play fiddle, mandolin, and banjo.

The “Dueling Banjos” scene from the 1972 film “Deliverance.”

“Another encounter was later on, I’d say the early ’60s,” Mahal continues, “when I was a member of the Elektras, the group I was with at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst. We were playing one day on campus, and after we took a break, a Dixieland band started up and this banjo player started doing ‘Fly Me to the Moon.’ I was like, ‘Wait a second, let’s see what this is all about.’ So I walked over, and there was this very well dressed, very sophisticated, African American gentleman playing with some younger guys—they wanted to learn Dixieland and he was showing them a lot of different tunes. I ended up talking to him during his break about the banjo, how much he loved the instrument, and how his dad and uncles and aunts and everybody in his family played it. Pretty soon, I had to get back to what I was doing, but it was really great because he was so friendly and open.”

Mahal also benefited from the folk revival started by Pete Seeger and others. “Once that whole movement was happening at the Newport Folk Festivals,” Mahal says of the famous 1960s concerts in nearby Rhode Island, “I really got the chance to see and hear the instrument up close.” And, of course, there were resources at UMass. “There were a lot of people on campus that played banjo,” Mahal remembers. “I got involved with the folklore society, where we heard a lot of people play different kinds of styles of drop-thumb, clawhammer, double-thumb, and three-finger picking styles, all kinds of stuff. So there was a sufficient amount of information to get me interested and to stay with it until I eventually met people who knew how to play the original West African instruments.”

Dubois’s professional interest in the banjo also came by playing it. “I started playing the instrument over a decade ago,” he says. “I realized, though, that if I really wanted to understand the banjo, I had to understand its context. It wouldn’t be what it is if it wasn’t connected to all these different histories in Africa, the Caribbean, the South. The history of the instrument is one of the things that actually makes it so powerful. It’s not just a sonic object but a cultural symbol. There’s probably no instrument in the world that’s had more stuff projected onto it.”

Buck Owens (left) and Roy Clark on the “Hee Haw” television show, circa 1975.

Which, finally, brings us back to those jokes. By the end of reading The Banjo, you may think you know where those jokes comes from, and you’d be right if your suspicion is that they are rooted in racism. But just as it’s too imprecise to say the “banjo” is an “African” instrument, it’s also too imprecise to say that all banjo jokes are rooted in the same type of racism. The question is, which flavor?

I put that to Greg Adams, who is the Smithsonian’s banjo guy (not his actual title, but you get the idea), an avid banjo player, and a tireless advocate for the instrument. Not surprisingly, Adams has heard more than his share of banjo jokes.

“When someone comes up to me and says, ‘Hey, do you know any good banjo jokes?’ I’m like, ‘Well, do you want to go back to the late 18th century to look at Colonial songsters poking fun at enslaved persons, or are you looking for something from the blackface minstrelsy era, where maybe you’ve got an Arkansas traveler denigrating somebody of African American descent? Or perhaps you’d like something more recent, say the late 19th century, a coon song, in which the racism is in overdrive. Or, we can do the “Hee Haw” thing, where the racism is built on top of stereotypes of white ruralness.’

“In other words,” Adams continues, “when I look at what’s going on with all these jokes from the vantage point of the 21st century, they are all extensions of the same continuum, of cultures clashing and coming together. Eventually, you get past the jokes enough to ask the more interesting question about the banjo: ‘What does its history actually mean?’”

Andy Thorn of Leftover Salmon represents the latest generation of musicians to pick up the banjo.

For Taj Mahal, the answer to that question is simple—music.

“In this country,” Mahal says, “everything moves really fast, and if you don’t get a good perspective, from far enough away, you can’t see the changes. You might even assume that something’s gone, finished, because it doesn’t have a popular expression that’s being promoted in the marketplace. For a while, the ‘Nashville Mafia’ managed to shut down steel guitars, banjos, and mandolins, but there are still lots of bands—the Carolina Chocolate Drops, Leftover Salmon—that don’t worry about what the trend is. Play some music, that’s the point. It shouldn’t have to be ‘indigenous music,’ ‘folk,’ or ‘the blues,’ put in some box off to the side because it’s not commercial. Culture is more important than making money.”

(“The Banjo: America’s African Instrument” is available from Amazon. If you buy something through a link in this article, Collectors Weekly may get a share of the sale. Learn more.)

Youngbloods Guitarist Banana Talks Vintage Banjos and the Late Earl Scruggs

Youngbloods Guitarist Banana Talks Vintage Banjos and the Late Earl Scruggs

Anita Pointer: Civil-Rights Activist, Pop Star, and Serious Collector of Black Memorabilia

Anita Pointer: Civil-Rights Activist, Pop Star, and Serious Collector of Black Memorabilia Youngbloods Guitarist Banana Talks Vintage Banjos and the Late Earl Scruggs

Youngbloods Guitarist Banana Talks Vintage Banjos and the Late Earl Scruggs How America Bought and Sold Racism, and Why It Still Matters

How America Bought and Sold Racism, and Why It Still Matters BanjosWhen traders brought African slaves to America, the slaves brought their ow…

BanjosWhen traders brought African slaves to America, the slaves brought their ow… Sheet MusicThe publication of folio-size sheets of American popular music dates to the…

Sheet MusicThe publication of folio-size sheets of American popular music dates to the… Black MemorabiliaBlack memorabilia, sometimes called Black Americana, describes objects and …

Black MemorabiliaBlack memorabilia, sometimes called Black Americana, describes objects and … Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Okay, okay, we get that you are really sensitive, nice, correct thinking people.

Now see if you can go a month here without running an item that has no subtext of preening virtue signaling.

Thanking you in advance.

Great article.

I, for one, enjoy the history and context that you provide in your very well written articles. What good is being a Collector if you don’t know the history behind your collection? There’s a lot of history in America that is nothing to be proud of. Perhaps that is why so many prefer to remain ignorant.

I had no idea of the historical roots of the Banjo. Thanks for taking the time to share some knowledge.

Your article is very well written, I have been playing the banjo since 1959/60 and am as interested in it’s history and place in our culture now as back then. I am disturbed by the denial of the banjo’s African origins by some banjo players. Not only are there similarities between the gourd lutes of Africa and the “modern” banjo but there is similarity of playing style as well. I have mixed feelings about the minstrel era but I think I should be grateful that it brought the banjo firmly into our musical culture. All music enthralls me. My late uncle was a jazz musician who learned his music and developed his styles of playing (he played violin, guitar and tenor banjo) during the 1920s. He had a very high opinion of the music of black jazzmen and other artists who migrated to his native Chicago and adapted some of their playing styles to his own repertoire. The banjo could be viewed as an instrument capable of bridging cultural and racial gaps that it hasn’t been is just one more aspect of the sad tale of this country’s history.

Thanks for presenting this article and thank you also for presenting material from Laurent Dubois’ excellent book. I play numerous kinds of banjos, including an akonting I made from local materials and some fishing line and I play in various “styles”. Bluegrass music is morphing these days. Musicians like Steve Martin incorporate claw hammer style and “atypical” tunings and current discussion and innovation accept the banjo’s African origins as well as incorporating older (plantation derived) styles.

Thanks again;

Tom

Great Article!!

Thomas.

America owes so much to the african race. At the risk of being a musical racist, may i say shame on white america for not aknowlaging the wholly unique way they express art.”the banjo”sounds like a facinating peice of work. Perhaps pete seeger cleansed the banjo.In his hands it became an instrument to accompany words of longing for freedom. Shame on white america. But after all it is not the instruments fault.Shame on white america.Thank god for the banjo.MS

Great article! Be sure to check out Otis Taylor’s 2008 release “Recapturing the Banjo”.

https://www.allmusic.com/album/recapturing-the-banjo-mw0000582421

I disagree that banjo is a racist reinvention, it came from Joel Sweeny appreciating the sound of the slave’s music and wanting to make great music with what he could create that was similar. It was born of admiration, and unfortunately was caught up in the social craziness of the day with the minstrel shows. But even then, the people went to the shows to enjoy the sound of the banjo. As I see it the banjo has the capability of bringing people of all color together in sharing the wonderful sound of the music. It is a symbol of freedom and if we focus on creating freedom everywhere for all people racism will fall away and the music will prevail.

Interesting piece. However, the fifth/top/short string on a five string banjo is the highest, not the bass as was stated here: “And just like on modern-day banjos, the shorter top, or bass, string is played with the thumb.”

I’m surprised Bela Fleck was not included here. Besides Bela’s prodigious talent at playing any kind of music on the five-string, he produced a video in which he traveled to Africa, and met and played Africa’s native “banjo” music with many of the indigenous musicians there. The video is entitled “Throw Down Your Heart,” an homage to the feeling at the time of these slaves who were kidnapped and brought to the Western Hemisphere centuries ago. One of these musicians told Bela its meaning: “We threw down our heart because we knew we’d never see our home again.”

Yes! I see someone else has id’ed Otis Taylor’s playing. He & Rhiannon Giddens are the best banjo players in existence.

I play the banjo. It IS nearly impossible to keep in tune for long, because it has the longest neck of the stringed instruments, and its bridge is anchored to a flexible material. Watch Steve Martin and the Steep Canyon Rangers on YouTube. He is tuning constantly – no one else is (well, except the other banjo player).

In fact, its tuning fluctuates with any change in pressure of how you anchor your picking hand or rest your wrist against it. Or flex the neck – which is deliberately done in many songs.

Struggling to see how the ‘you can tune a car’ joke has racist beginnings… or the other jokes.

well to be fair you havent actually havent done your research. the african banjo may have been the inspiration for white music in america, but the banjo itself is not african. it is middle eastern as archaeologists have found examples of primitive banjos in from ancient egypt. in asian cultures such as china and japan they have their own versions which couldve come from the middle east. the “sanxian” from china and the japanese “shamisen”. youtube shows chinese musicians playing what sounds similar to bluegrass music with the “sanxian”. but I get what you are saying, Ben, white people tend to appropriate from other cultures and then claim that they invented it. cultures far older than america probably played bluegrass music before america even existed. here is a video of a chinese musician playing the “sanxian”, sounds very western/cowboy. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wSPXjbbTeoM&list=RDyIIWV-sGEzA

here is another video of a chinese musician playing the “sanxian”, sounds very western….https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HkTOlCTKBEM

If you loathe the banjo because it HAPPENED to appear in, say, a black minstrel or was somehow racist two hundred years ago, you are a fool. There is nothing racist about a banjo in modern times and to be triggered or offended by its continued use is ridiculous.

As one actual banjo player noted, BTW, the banjo is apparently hard to tune and that is why the joke comes out of it.

The gourd banjo was African and the ‘Strum Strump’ banjo was from the Caribbean but Sweeney created the 5 string banjo and it was developed from there. The down stroke playing style was from Africa but later the finger style came along and the modern banjo was born with S.S. Stewart. By the early 1880s the banjo was a concert instrument and totally removed from any links to Africa. There were few African banjo players around until Horace Weston and all the developments with the instrument was done by white banjoists and makers. The Sweeney banjo began the white connection to it and it went from there. Musical trends took it out of the Minstrel show tradition and it became a refined instrument. The banjo developed over time and evolved just like other instruments did so the early link to Africa was

not so much denied in the 1880s but questioned as it’s origin. George Dobson in 1884 said that it was from Egypt. The bottom line is that the banjo of today owes nothing to the gourd banjo which arrived from Africa and the Caribbean, it’s a different instrument. The banjo has no racism, that’s a human fault but I know that it is enjoyed by so many people today irraspective of colour.