Syrena-Electro was Poland’s premier manufacturer of Polish tango records between World War I and II. This catalog is from 1934. Courtesy Juliette Bretan.

Have you ever woken up on the couch in the middle of the night to find yourself staring at a black-and-white movie from the 1930s flickering on the TV? If so, your slumber may have been gently stirred by the film’s melancholy soundtrack. Drifting between dreamstate and consciousness, at first you may think you recognize the tinny strains of a slow Argentine tango, but then you discern a melody suggesting a Chopin nocturne, albeit one that’s been tuned to an even gloomier minor key of an Eastern European klezmer dance number. Perhaps you’re still dreaming?

“Polish tango was at the heart of Syrena’s repertoire, and Jewish composers working for Syrena penned and performed the label’s most popular numbers.”

In fact, you’re wide awake, and what you’re hearing is a Hollywoodized version of Polish tango, a popular genre of sentimental songs composed between 1918 and 1939 by classically trained Polish musicians, many of them Jewish. “That’s the soundtrack of interwar Poland,” says Juliette Bretan, a journalist and researcher based in Lincolnshire and studying in London. “The music is very melodramatic and really rather sad, filled with these depressing lyrics about people wanting to take their own lives, or the fights they’re having with their lovers. But it’s also a very mature sound, a very Polish sound. Had World War II not happened,” she adds, “I believe Polish music would’ve had an even bigger impact than it did on the global stage.”

At first blush, Bretan might not seem like precisely the sort of person to champion this fusty and largely forgotten genre. Born in the U.K., Bretan is a musically disinclined recent graduate of Cambridge—“I got about as far as grade one on the piano,” she admits—and while her father’s non-Jewish parents were from a part of interwar Poland that’s now called Ukraine, her grandmother Maria died when she was barely a toddler, and she never met her grandfather Gregory at all.

A Warsaw street scene from the 1930s. Notice the signs in both Polish and Yiddish. Via Rivka’s Yiddish.

That probably explains why in recent years Bretan has been on a mission to learn about her Eastern European roots. “We know my grandmother was taken from Poland in 1941 to perform slave labor in Germany,” Bretan says. “We think she was in some camps for a time, but it’s very unclear. After the war, she met my granddad in a displaced-persons’ camp, but we don’t really know what happened to him before that. They married and then came here in ’46 or ’47, and that was that.”

As Bretan delved into her family’s history, Polish tango became her soundtrack. “I stumbled onto this music purely by chance,” she says. “I find the sound intoxicating, so it became a connection to the world my grandparents would’ve known when they were living in Poland. On the one hand, for me, the music is like a reconnection to my heritage, but on the other hand, what is there to reconnect to? That heritage is all gone, so it’s almost like I’m writing a new history of my family.”

The Artur Gold (conducting) and Jerzy Petersburski (on accordion) band, circa 1930s. Via Wikimedia Commons.

Bretan fell hard for Polish tango, which, in an article for culture.pl, she described as “merging pinches of the age-old Polish romantic and sentimental melodies with Jewish inflections and a more modern, brassy sound, dripping in glissandos and vibrato.”

The Jewishness of Polish tango is essential to understanding the source of these sounds, which means it’s important for those of us in 2020 to understand what it must have been like to be Jewish in Poland during the interwar years. Briefly put, it was no picnic, in particular because of the overt antisemitism of the popular National Democratic Party, which organized successful boycotts against Jewish-owned businesses. For the fascists and racists who waved the banner of the NDP, antisemitism was nothing less than a prerequisite to Polish patriotism.

Even so, being a Jewish composer, musician, or performer in Warsaw, whose population between the wars was roughly one-third Jewish, offered Jews a rare measure of personal and professional freedom. That’s because many interwar Poles, whose country’s borders had been erased from maps by Russia, Germany, and Austria in the late 18th century, were ready to celebrate their nation’s newfound independence. Thus, for large swaths of the Polish population, especially those in Warsaw, Jewish composers, musicians, and performers were tolerated, and even welcomed, to the extent, that is, that they were entertaining.

Clockwise from top left: A 1920s Syrena Grand Rekord disc in Ukrainian. Via eBay. Melodia Electro was the company’s bargain brand for new artists, pressed on inferior shellac. Via culture.pl. In the 1930s, Syrena-Electro pressed Hebrew-language discs for Eastern Europeans who had fled to Palestine. Via eBay. “Rebeka” was a popular Polish tango hit with Jewish themes. Via eBay.

Among the many fascinating aspects of Polish tango is the fact that the musical members of Warsaw’s Jewish community took at least some of their inspiration from their counterparts in Buenos Aires, which boasted one of the planet’s largest Jewish populations during the interwar years. The Jewish immigrants living there had fled less welcoming corners of interwar Poland than Warsaw, as well as Russia and Romania. Some of them arrived in Argentina with violins in hand, and it didn’t take long for these enterprising musicians to find their way into nightclubs, where tango was king; for a while, Yiddish tangos even became a thing in Argentina. Soon, word of the tango’s charms had made it back to the old country, where the musically inclined friends and relations of these fiddlers gave the Argentine tango a Polish twist.

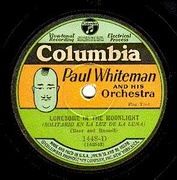

The tango also came to interwar Poland via the ascendant technology of radio, as well as American recordings of Swing Era jazz pressed onto 10-inch, 78 RPM shellac discs, which brings us to a Warsaw music company called Syrena. Before the Great War, Syrena sold Edison phonographs in Poland, and even manufactured a Polish-label gramophone—an invention of a German-Jewish immigrant to the United States named Emile Berliner—of its own. Syrena also recorded, produced, and distributed 78s of patriotic songs, folk music in Russian, Polish, and Yiddish, and the proto-jazz genre of klezmer.

“Tango Milonga” was interwar Poland’s biggest tango hit. Via staremelodie.pl.

Before World War I interrupted its ambitions for global expansion, Syrena had contracts to distribute a portion of the 4.5-million records it was pressing annually into the United States and the U.K. After the war, Syrena initially struggled, but it soon became one of the leading music companies of newly independent Poland. The optimism that accompanied the resulting new sense of Polish pride resulted in large audiences for new Syrena recordings of contemporary dance music, including the tango. Business was so good that by 1929 Syrena was able to build itself a state-of-the-art recording studio on Wiśniowa Street in Warsaw, an act of modernization that it celebrated by renaming itself Syrena-Electro and updating the romantic graphics on its record labels in stylish Art Deco.

“In the West,” Bretan tells me, “we’re kind of preprogrammed to think of interwar Eastern Europe as an economic and technological backwater. But by the 1930s, Syrena-Electro was recording operas, stage plays, and all sorts of classical and contemporary music, which it sold internationally. While its catalog was certainly inspired by what was happening in London and Paris, Syrena was definitely on par with its international competitors.”

Polish tango was at the heart of Syrena’s repertoire, and Jewish composers working for Syrena penned and performed the label’s most popular numbers. First among equals was the prolific Andrzej Włast, who, in 1929, co-wrote “Tango Milonga” with Jerzy Petersburski, who Breton calls the father of Polish tango. Petersburski’s cousins, brothers Artur and Henryk Gold, also wrote and arranged scores of tango hits for Syrena, including the ones with that “modern, brassy sound, dripping in glissandos and vibrato” that Bretan described in that aforementioned article at culture.pl.

Sheet music for “Tango Milonga”—here translated into English as “Oh, Donna Clara”—as performed by Al Jolson on Broadway in 1931. Via eBay.

Other tangos were certainly hits for Syrena, but it was “Tango Milonga” that fueled the genre’s popularity. Given new lyrics in German and then English as “Oh, Donna Clara,” “Tango Milonga” was even performed on Broadway in New York City in 1931 by the legendary entertainer Al Jolson, who was starring in a musical called “The Wonder Bar.” That production, blackface scenes and all, eventually made its way onto the silver screen in 1934—how it may have gotten onto your television set in the middle of the night is anybody’s guess.

For collectors, records bearing the Syrena-Electro label are prized, usually selling for between $100 and $200. The label’s Art Deco design features a lyre at the center, flanked by a pair of gramophone horns, all set against a graphic sunburst. The lyre and gramophone horn were picked up from earlier, more romantic label designs, when Syrena-Electro was known as Syrena Grand Rekord; the artwork for the labels of that earlier incarnation of the company included depictions of winged, mythical sirens. Collectors also look for copies of discs in Syrena’s catalog that were translated into Hebrew for the expatriate community of Jews who, during the 1930s, left the increasingly hostile environment of Eastern Europe for Palestine. Also collected are Melodja Electro discs, which was Syrena’s bargain brand that pressed discs out of inferior batches of shellac, along with Syrena album covers and sheet music of Polish tango hits.

Nazis evicting the last remaining Jews living in Warsaw for relocation to death camps, 1943. Via Wikimedia Commons.

Unfortunately, we know how this story ends. In 1939, Hitler’s troops marched into Poland and rounded up those Jews who had not fled to places like Argentina and Palestine. Andrzej Włast and countless others were murdered by the Nazis; before his murder, Artur Gold was reportedly forced to perform Polish tango numbers for his Nazi captors dressed as a clown. Henryk Gold and a few other lucky ones who saw the handwriting on the wall got out before the Germans marched in; they went on to make music after the war in Israel, New York City, and Hollywood. For the most part, though, the death of interwar Polish tango was merciless and bloody.

Nor was Syrena-Electro itself spared. In the first few days of the Nazi occupation of Poland, Syrena’s factory was bombed, and within about a year after that, Syrena’s chairman, Hilary Tempel, was unceremoniously shot. Even the recordings of Poland’s most famous classical composer, Frédéric Chopin, were destroyed—in the eyes of the Nazis, it was bad to be Jewish, but it was just as bad to be an accomplished Pole—as if the mere smashing of shellac could erase Chopin’s musical legacy from history.

In the end, that’s the thing about music: It stays with us, especially in the darkest times. “This music speaks to me,” Bretan says simply. “It takes the melodrama of the Argentine original, adds quivering vocals and sharp instrumentation, and blends Jewish musical history with Polish musical traditions to create something that’s very distinctly Polish but also distinctly not Polish, which is what makes it so enchanting. It traverses borders, history, and time. I think that’s why I love it so much.”

Warsaw Sentimental Orchestra is one of many contemporary Polish bands reviving the music of Poland’s interwar period. Photo by Karolina Majewska.

Today, Bretan is not alone in her affection for this sound, whether it’s interwar Polish tango or interwar Polish swing. “A lot of bands in Poland are reviving interwar music right now,” Bretan says. “Younger bands, too, not just older musicians trying to recreate songs they might have heard in the 1950s after the war. There seems to be a general revival of the 1920s going on,” she adds, “I guess because it’s the ’20s again.” That sounds pretty hopeful, but given what we know about the interwar years, let’s hope that a repeat of 1930s Poland isn’t also right around the corner.

(To learn more about interwar Poland, visit Juliette Bretan’s page at culture.pl or her blog.)

A Frenzy of Trumpets: Why Brass Musicians Can't Resist Serbia's Wildest Festival

A Frenzy of Trumpets: Why Brass Musicians Can't Resist Serbia's Wildest Festival

Why Nerdy White Guys Who Love the Blues Are Obsessed With a Wisconsin Chair Factory

Why Nerdy White Guys Who Love the Blues Are Obsessed With a Wisconsin Chair Factory A Frenzy of Trumpets: Why Brass Musicians Can't Resist Serbia's Wildest Festival

A Frenzy of Trumpets: Why Brass Musicians Can't Resist Serbia's Wildest Festival Spinning at 78 RPM with Record Collector Gary Herzenstiel

Spinning at 78 RPM with Record Collector Gary Herzenstiel 78 RecordsBefore iTunes, CDs, 8-tracks, LPs, or even seven-inch EPs, 78s were the mai…

78 RecordsBefore iTunes, CDs, 8-tracks, LPs, or even seven-inch EPs, 78s were the mai… Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Interesting article.

However, I’m going to soapbox here because I am dismayed by the repetition of the by now widely accepted uninformed mischaracterizations of interwar Polish-Jewish relations through various vague insinuations. I wish I didn’t have to do this, but hurtful, even hateful, untruths will become accepted as truth if such claims are allowed to continue and left unaddressed.

“Briefly put, it was no picnic, in particular because of the overt antisemitism of the popular National Democratic Party, which organized successful boycotts against Jewish-owned businesses. For the fascists and racists who waved the banner of the NDP, antisemitism was nothing less than a prerequisite to Polish patriotism.”

“Antisemitism” is a racial or ethnic hatred of Jews. The quotidian anti-Jewish sentiment that existed during the interwar period in Poland, when it existed, was not racial or racist in character. It was largely economic in nature and based in grievances having to do with the dominance of Jews in certain occupations, economic classes, especially where these intersect with questions of national allegiance. These must be interpreted in the context of the prevailing historical and political conditions. Neither fascism nor racism were meaningfully represented in Poland. People have simply gotten lazy and used to interpreting nationalism entirely through the lens of, e.g., German racial theories, whereas in Poland, national allegiance and cultural affiliation were much more important questions. Whom the Jews were loyal to was the “Jewish Question”, not your ethnic origins (the countless examples of assimilated Polish Jews provide such an example). Furthermore, the subject of Polish-Jewish relations is always covered in a superficial way. For example, if you speak with Poles who lived during that period, many will tell you of their experiences with Jews who harbored anti-Polish attitudes and looked down on the so-called goyim (e.g., by refusing to let their children play with non-Jews). Sadly, Polish-Jewish relations are always portrayed in a childish, simplistic, one-sided, black and white manner. The ignorance of journalists who merely parrot these bigoted sentiments does not help (using offensive phrases like “Polish concentration camp” is but the tip of the iceberg).

“Even so, being a Jewish composer, musician, or performer in Warsaw, whose population between the wars was roughly one-third Jewish, offered Jews a rare measure of personal and professional freedom. […] Thus, for large swaths of the Polish population, especially those in Warsaw, Jewish composers, musicians, and performers were tolerated, and even welcomed, to the extent, that is, that they were entertaining.”

Where does the author get such an idea. Poland was home to the largest number of Jews in the world at the time and had been for centuries as the “Paradisus Judaeorum”. To this day, you can still find older Jews who will tell you that. The way the author writes makes it seem like Poles merely tolerated Jews as long as they managed to be entertaining. What nonsense. Jews have been involved in entertainment in many countries, including Hollywood (which was established by Polish Jews).

“The Jewish immigrants living there had fled less welcoming corners of interwar Poland than Warsaw […] left the increasingly hostile environment of Eastern Europe for Palestine.””

Again, the insinuation is that Warsaw and broadly interwar Poland was a menacing place for Jews. An honest, historically literate person will know that’s untrue.

“That sounds pretty hopeful, but given what we know about the interwar years, let’s hope that a repeat of 1930s Poland isn’t also right around the corner.”

More weasel words. This sentence perhaps takes the cake and ultimately motivated me to write this comment because it confirms my original suspicions. First, the author misrepresents the general character of interwar Poland vis-a-vis Polish-Jewish relations (which he smears earlier in the article as I’ve shown). But then, the author makes an unintelligible insinuation that, whatever the menacing eldritch forces of 1930s Poland were (insinuated, but unnamed), a specter of these hitherto unnamed forces is at hand in Poland. What an absurd thing to say.

Had the author stuck to the subject matter instead of using his article as a platform for repeating tired canards, it would have been a much more enjoyable read about an interesting period of history and an interesting part of the world that regrettably few people in the West know much about, yet who believe many bigoted stereotypes about (some of which have their origins in Nazi/fascist propaganda and imperialist smear campaigns launched by, e.g., Germany to justify their claims on Polish soil). It’s a shame that these canards serve as an introduction on the subject.

(For those interested in Polish-Jewish relations, I have been told that Iwo Cyprian Pogonowski’s “Jews in Poland” is a good read.)