Every day, exciting new technologies and inventions designed to make our lives better make us crazy instead—if we’re lucky. A document you’ve been working on all day disappears from your computer, having been saved to an obscure folder you didn’t know existed; a social-media app secretly shares your personal information with Russian hackers, spawning a Constitutional crisis; a self-driving car kills a pedestrian, giving us yet another reason to fear the future. Indeed, it’s been quite a while since any invention could claim to be unreservedly useful (spoons come to mind), while most inventions of the digital kind have difficulty clearing even the low, Hippocratic hurdle of doing no harm.

“Goldberg recognized that staring at screens had become a national obsession.”

Rube Goldberg (1883-1970) understood well the limits of improvement through invention, as a new exhibition of his drawings and cartoons at the Contemporary Jewish Museum in San Francisco hilariously shows. Armed with little more than a pen and the laws of physics, Goldberg routinely pushed his ideas for inventions to their preposterous conclusions, solving problems that didn’t exist and making the simplest acts of everyday life as complicated as possible. Thus, a contraption worn on the head to wipe one’s lips with a napkin after sipping a spoonful of soup consists of no less than 14 moving parts, most of which must be reset after a single use. That device was memorialized as a U.S. postage stamp in 1995, but an even sillier “appliance” from 1929, concocted by Goldberg’s editorial alter ego, Professor Lucifer G. Butts, could lick a stamp in just 16 steps, with the help of two adults and a dog, of course.

Top: In 1995, a U.S. postage stamp honored the life and work of Rube Goldberg. Above: An invention for licking stamps from 1929. Artwork Copyright © Rube Goldberg Inc. All rights reserved. RUBE GOLDBERG ® is a registered trademark of Rube Goldberg Inc. All materials used with permission. rubegoldberg.com.

Born on the Fourth of July in San Francisco, Goldberg lived during a time of tremendous technological change. As a young man, Goldberg was part of a generation that came of age as cameras, telephones, and automobiles were becoming commonplace. As an adult, Goldberg joined younger generations in embracing radio, movies, plane travel, and television.

These experiences informed Goldberg’s impractical drawing-board inventions, not so much for the mechanical details he may have occasionally pillaged but for the way in which Goldberg’s pen-and-ink characters blindly trusted their creator’s inventions to improve their lives. Goldberg’s readers, however, were not so easily duped. From the 1920s through 1960s, when Goldberg’s inventions were running in newspapers and magazines—eventually, they were also turned into puzzles and toys—Goldberg’s mustachioed and bald-headed rubes always struck his readers as fools, as ridiculous as someone wearing a pair of Google glasses looked to just about everyone in 2014, except, apparently, Sergey Brin.

One of Goldberg’s earliest successes was a series of cartoons called “Foolish Questions.” Artwork Copyright © Rube Goldberg Inc. All rights reserved. RUBE GOLDBERG ® is a registered trademark of Rube Goldberg Inc. All materials used with permission. rubegoldberg.com.

Goldberg honed his antenna for foolishness early, when a cartoon titled “Foolish Questions” proved the first big break of his career, launching a series of the same name. Published on and off from 1908 to 1941, the humorous parts of Goldberg’s “Foolish Questions” were not so much the questions as the answers. When one character who’s target shooting is asked if he’s target shooting, the shooter replies, “No, I’m fishing for locomotive wheels in a platter of beef stew.” All readers see are two men and a target, but Goldberg knew that their minds would be filled with visions of someone actually fishing for locomotive wheels in a platter of beef stew. His mind was, too, and soon such absurdities were filling his cartoons.

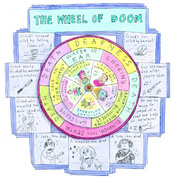

Various inventions, c. 1938-1941. Color ink and watercolor on paper. Artwork Copyright © Rube Goldberg Inc. All rights reserved. RUBE GOLDBERG ® is a registered trademark of Rube Goldberg Inc. All materials used with permission. rubegoldberg.com.

Over the years, a rogue’s gallery of curious characters also filled Goldberg’s cartoons, some given formal names—Mike & Ike, Lala Palooza, Boob McNutt—some generic—the recurring bald man with the bushy mustache, any number of stylish flappers in silly hats. Mostly it was all in good fun, but often Goldberg’s unease with technology, the subtext of his inventions, came to the fore in his political cartoons of the 1940s and ’50s. In one memorable drawing titled “The Numbers Blues,” Goldberg collected all the numbers that were beginning to define people’s lives and took them to their logical and unsettling conclusion, finding little difference between citizenship and prison.

Left: “The Numbers Blues,” c. 1940s-’50s. Right: “Forbes” magazine cover, 1967. Artwork Copyright © Rube Goldberg Inc. All rights reserved. RUBE GOLDBERG ® is a registered trademark of Rube Goldberg Inc. All materials used with permission. rubegoldberg.com.

Even more striking is his cover for “Forbes” magazine from 1967. Drawn a full year before computer scientist Doug Engelbart delivered his famous “Mother of All Demos” in December 1968, in which he demonstrated what an Internet-connected world might look like several decades before anyone knew to call it that, Goldberg recognized that staring at screens had become a national obsession, an observation he dutifully carried to its disturbing conclusion, albeit in a humorous way. Engelbart may have gotten the technical details of our future right, but it was the cartoonist Rube Goldberg who understood the true impact technology would have on everyday people.

(“The Art of Rube Goldberg” continues through July 8, 2018, at the Contemporary Jewish Museum. For a terrific book about the life and work of the artist, pick up a copy of “The Art of Rube Goldberg,” which was organized by his granddaughter Jennifer George. And for more information about Rube Goldberg, visit rubegoldberg.com. If you buy something through a link in this article, Collectors Weekly may get a share of the sale. Learn more.)

What Makes Cartoonist Roz Chast Laugh?

What Makes Cartoonist Roz Chast Laugh?

Someday, Robots May Save or Destroy Us All—For Now, They're Still Kinda Dumb

Someday, Robots May Save or Destroy Us All—For Now, They're Still Kinda Dumb What Makes Cartoonist Roz Chast Laugh?

What Makes Cartoonist Roz Chast Laugh? Don't Panic: Why Technophobes Have Been Getting It Wrong Since Gutenberg

Don't Panic: Why Technophobes Have Been Getting It Wrong Since Gutenberg DrawingsThere’s an immediacy to drawings that is not always present in paintings on…

DrawingsThere’s an immediacy to drawings that is not always present in paintings on… NewspapersAlmost everyone has an old newspaper cover or two tucked away somewhere - a…

NewspapersAlmost everyone has an old newspaper cover or two tucked away somewhere - a… Comic BooksComic books have been published for more than a century, and collectors cat…

Comic BooksComic books have been published for more than a century, and collectors cat… Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Rube is a genius indeed. He knows what technology could do and where lead the humans in the future.