See Red’s “Protest” poster from 1973. © See Red Women’s Workshop.

Self-proclaimed “nasty women” are everywhere these days: testifying in court against their rapists and abusers, marching in the streets to protest assault and objectification, and shouting #MeToo and #TimesUp across all forms of social media. Thousands of women have shared their stories of sexism and sexual assault over the last few years, continuing a centuries-long push for greater equality across the gender divide. Many of these women are driven by anger at the systemic structures that limit female autonomy, a familiar experience for women who lived through the second-wave feminist movement, which lasted roughly from the 1960s through the 1980s.

“It was important that the designs would be easily understood by everybody; that there was nothing ambiguous about them.”

In 1974, it was this pervasive sense of outrage that united several London women who wanted to challenge the demeaning images of women they saw all around them. The collective initially included several artists and graphic designers, a photographer, an illustrator, a cartoonist, and a filmmaker, and from its first statement of purpose, its goal was to counter the stereotypical images of women in media and advertising. The artists hoped to achieve this by producing their own posters, illustrations, and photos; providing visual material for women’s publications; offering poster-making facilities for other women; and building a collection of examples both of positive and negative images that indicated the status of women in the past, present, and future.

Eventually, the collective would become See Red Women’s Workshop, a printmaking cooperative established by Julia Franco, Suzy Mackie, and Pru Stevenson to create feminist posters for use at schools, universities, bookstores, women’s centers, and political rallies. Long before Hillary Clinton memes and pink “pussy hats,” See Red designed art to fight the patriarchy.

The cover of See Red Women’s Workshop: Feminist Posters 1974-1990 from 2017.

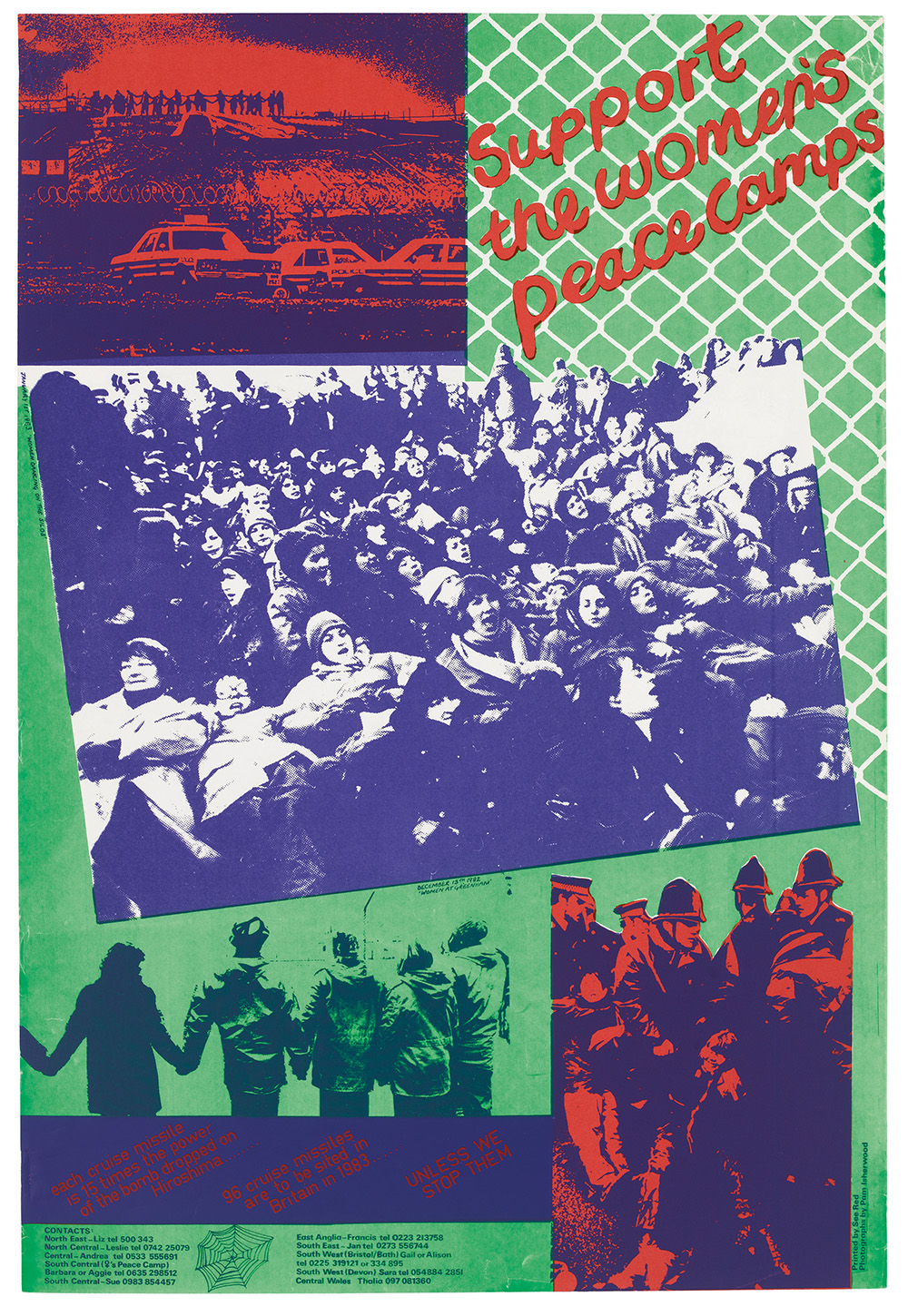

Their workshop was established during a turbulent time in UK politics, with women activists confronting political violence in Ireland; the importance of trade unions; issues around housing, hospitals, and child care; as well as access to contraception and abortion. The See Red collective first established their workshop at the Camden Tenants Association in North London, but soon moved their studio to the South London Women’s Centre, located in a squat, in 1975. Two years later, See Red secured a permanent location at Iliffe Yard, across from Women in Print, another print-based cooperative. In addition to developing its own posters and campaigns, See Red started taking commissions for posters beginning with the International Women’s Day March in 1975. After some of the group’s early posters were criticized as too negative, the collective worked to produce more uplifting poster designs like “Miss March” and “Girls Are Powerful” (both from 1979).

“See Red were not about selling a product or even getting over a party political message, they were about something far more complex and far more difficult,” Sheila Rowbotham writes in the introduction to the 2016 book, See Red Women’s Workshop: Feminist Posters 1974-1990. “They aimed to convey ideas about a transformed society in which relations of gender, race, and class would no longer be marked by inequality and subordination.”

By the early 1980s, See Red began seeking grants for funding, which allowed the workshop to upgrade its studio space and pay members for their work. However, the introduction of wages brought about a reckoning over who should benefit from this income, and the two founders still involved with the collective were asked to leave. After 1983, the workshop no longer designed its own posters and instead focused on classes, activism, and commissioned designs. Finally, in 1990, See Red fully dissolved.

Unfortunately, many of See Red’s political messages are still relevant today, as women continue to fight for legal rights, bodily autonomy, health care, equal pay, and more. We recently spoke to Pru Stevenson, one of See Red’s founding members, about the cooperative experience and its legacy of powerful poster art.

The “7 Demands” poster from 1974 included seven concepts developed at the National Women’s Liberation Conferences of the early 1970s. © See Red Women’s Workshop. (Click to enlarge.)

Collectors Weekly: What was the impetus for founding See Red Women’s Workshop?

Pru Stevenson: We answered an advert in a feminist magazine—none of us could remember which one it was—asking for women who did visual work to meet and discuss combating the very sexist imagery that was around at that time. There were three founding members, and one more joined about six months later. We were all art-school trained and did a mixture of painting, fine art, graphics, and film. We wanted to use our skills to further the cause of women’s liberation. See Red grew out of that initial meeting.

Collectors Weekly: Do you remember how the name came about?

Stevenson: Not really, no. I think it came quite easily. We were angry. We “saw red,” as it were. We were also all on the left of the political spectrum; we had socialist tendencies, so to speak. “See Red” answered that as well.

Collectors Weekly: What were the major political tensions in Britain at that time?

Stevenson: One of the main issues was The Troubles in Ireland. We all lived in London, and there were quite regular bombings and disruptions, so we were all very aware of it. It was the time of Bobby Sands’ hunger strike, and he died in 1981. It was also the time of Irish women in prison fighting for political recognition, rather than being seen as criminals. There was the big miners’ strike in the early ’80s. Housing and unscrupulous landlords were major issues, and race relations, as there were a number of riots at that time.

I also worked with a group of women to set up a women’s refuge in central London. It was the second refuge to be formed for women who were experiencing domestic violence. Not only were we looking at issues around women’s liberation, but we were all active in other ways, too.

“Girls Are Powerful” poster from 1979. © See Red Women’s Workshop.

Collectors Weekly: What was the status of women within the larger leftist movement at the time?

Stevenson: I think we were mainly seen as a distraction; we weren’t taken seriously. It was seen to be a side issue. Within our personal relationships, there were also issues around domestic work. It was very much seen as women’s work, and the men would say they had more important things to do. “I have to take on issues which are of state importance, and who does the housework or who looks after children isn’t important to me.” So our status on the whole was pretty low. We were very much marginalized within the Left and tended to be pushed into the kitchen, making cups of tea.

Collectors Weekly: How was See Red’s collaborative environment a reaction to the typical art-school experience?

Stevenson: Our main impetus was around women’s liberation, and our time at art school certainly reflected that to a certain extent. I studied fine art at St. Martin’s, and there were mainly male tutors there. There were also more male students than women, and they tended to take up a lot more space. Much of their work was absolutely enormous and was seen to be more important. If we wanted to work on issues relating to women, it was seen as a load of nonsense. We were largely thought to be wasting time until we got married, or that our art was just a hobby, a little side issue.

On the whole, it was very exciting to be there, and for myself, I found it tremendous. But it was very dispiriting as well. We were always having to fight for our corner. In those days, it was almost expected that you would lower your ambitions in order to support the men. Many women who have been extremely good artists themselves faded into the background during their lifetimes, like Frida Kahlo, Lee Miller, and Dorothea Tanning. There’s a big exhibition of Tanning’s on in London at the moment, but in life, she went right into the background and Max Ernst became the famous one.

Members of See Red working in the Iliffe Yard studio in 1982. © See Red Women’s Workshop.

There has always been this big mystique about the artist being a special sort of person with unique talents. And also the idea that you should never share your knowledge—whatever work you made was purely yours, and you alone should get the credit. On one level, that’s fine, but we wanted to share our expertise. We didn’t go along with that whole idea of being a special person, wanting to be better than anybody else.

Forming a cooperative came very easily to us. We felt absolutely right about it, but it was very difficult, too. You would start a design, and then somebody else might criticize it, and somebody else might want to do a bit of work on it. It was very difficult to say to your fellow workers, “I don’t think that’s good enough. I don’t really like that.” But we did learn to do that.

Collectors Weekly: How was the workshop linked to other women’s centers or organizations at the time?

Stevenson: We worked very closely with a group called Women in Print, who did offset litho, and we shared a darkroom with them. We worked from a little mews [row of houses] where there were lots of different workshops, so we shared some facilities. We also had regular meetings with other print workshops, and there were a lot around at that time as it was a strong movement in itself. We compared notes, shared some of our equipment, and one of the other print shops even came to help us set up our darkroom.

Some of our commissioned posters were for a women’s conference or a women’s taxi service or things like that, though we did the designs ourselves. If somebody wanted a poster around a particular issue, we’d encourage them to come in and work on it with us if they were able to. For instance, to create the one about women prisoners in Ireland [Support Our Sisters in Armagh Jail], we worked closely with Women Against Imperialism and another Irish women’s organization, Women & Ireland. We had a few meetings with them, and they would come in to comment on the design and so forth.

“Support Our Sisters in Armagh Jail” poster from 1979-1980. © See Red Women’s Workshop. (Click to enlarge.)

When See Red first started, we were three white middle-class women and very conscious of the fact that our life experience was limited. It was very important for us to go out and get other women who had a wide range of experience to come and join us. Forty-five women came through the workshop, in fact. We’d also go out to organizations and say, “This is an issue which we think is important. What are your views on it?”

Collectors Weekly: What were some of See Red’s aesthetic and political influences?

Stevenson: We were very influenced by Atelier Populaire [Popular Workshop], and their Paris May ’68 posters. We very much liked their directness. Chinese cultural posters, we thought, were magnificent—amazingly lively, strong, and colorful. In the ’80s, there were also lots of South African anti-apartheid posters that were terrific. The Paddington Printshop did great posters locally in London, and Lenthall Road Workshop, another women’s organization, also did great posters.

“There’s an awful lot online, but it’s all very fleeting—there isn’t much that has permanency, that people can put up on their walls.”

The most important thing for us was that our posters were easily understood. You could look at them and realize immediately what they were about, and the slogan or the caption was very direct. One of the things we had the most discussions about, and perhaps the most arguments, was the captions or what the posters should say. It was important that the designs would be easily understood by everybody; that there was nothing ambiguous about them. Humor was quite an important part as well. We didn’t want them to be too heavy and thought that humor would make the posters more accessible.

The other thing that was really important for us was that they were well done, that the standard was good. They left the workshop as good prints. There were virtually no women in the printing industry at that time, and we were very open to being criticized. “Oh, you know, they can’t do it properly. Look how sloppy it is. Typical women’s work.” So it was very important to us that they were of a high standard.

Collectors Weekly: How did See Red raise money for its projects?

Stevenson: We received a number of donations, and people helped us along. When a print workshop or business was closing down, we used to go and get very cheap paint and paper. We all worked part time, and didn’t get any wages from See Red at the beginning. We all did two-and-a-half days or so a week. It wasn’t easy.

Our equipment was extremely basic. We started off with a washing line and pegs for hanging the posters on to dry. And then we got proper drying racks and screen-printing tables. Health and safety was not considered at that time at all, so we were often printing in conditions which would be banned now, I think. But eventually, we were able to get extractor fans to help with the fumes.

“Don’t Let Racism Divide Us” from 1978. © See Red Women’s Workshop.

Everything was done on a shoestring budget, and we did rely on a certain amount of outside help. Then we also did work for outside organizations, depending on the status, and charged them what they could afford. And we did sell our posters; they were very popular. Schools, colleges, and universities bought them. There were annual conferences—we sold an awful lot then, and also by mail order. There were a lot of alternative bookshops in London and throughout the UK at that time, and we sold many posters through them, mostly word of mouth. We had catalogues, and people would write in and place orders, or people just saw our designs, liked them, and wrote in to order them. Again, it was important to us that they weren’t just for those who could afford them, so we kept them as cheap as we possibly could.

Collectors Weekly: How was See Red targeted by right-wing fascist groups?

Stevenson: The National Front [a far-right, fascist political party in the UK] was very active at that time, and sadly it’s becoming active here again now. We were targeted by them, and they trashed our workshop: They poured ink all over, urinated all over, and generally made an awful mess. They wrote “NF” on the walls, and when the police came, we pointed the initials to the police, saying, “This is obviously who’s done it, the National Front.” And the police said, “Oh, no, no, no. It could be a man’s initials, like Nicholas French or something like that.” To a certain extent, some of the police were sympathizers with the National Front themselves. Our workshop was located in a known stronghold for the National Front, so we had to reinforce it and look at ways of escape in case anything happened, if we were fire-bombed or something.

We had another similar experience—we squatted a shop right at the very beginning, and we produced a number of posters and put them in the shop window. Within 48 hours, we got a brick through it. I don’t know whether that was the National Front or not, but it was obviously people who objected very strongly to our message.

“YBA Wife” poster from 1980. © See Red Women’s Workshop.

Collectors Weekly: Did these attacks affect the work you were doing?

Stevenson: No, they didn’t. We always made sure that there were at least two or three people in the workshop at any one time. There was never anybody there alone. We had a telephone system so that if ever we were anxious, we could ring for reinforcements to come and help us. But no, if anything, it redoubled our efforts to do more. There’s no way we were going to be seen to be in any way afraid or browbeaten by them.

Collectors Weekly: What types of internal conflict did See Red have to overcome?

Stevenson: On the whole, we worked pretty well together. That’s not to say we didn’t have our arguments and upsets, but we were well organized, and that helped. We always kept a daily diary, so when you came into the workshop, you knew pretty well what had to be done. We had fortnightly or monthly meetings where we were able to talk about things if we had any grievances.

“It was very important for us to go out and get other women who had a wide range of experience to come and join us.”

Towards the very end, a number of young women joined the workshop as core members, which was badly needed, and it was at a time when we got a grant to pay wages for the first time. It was felt that those wages should go to the younger women with a different life experience to ours [working-class women and women of color], and that was difficult but it was almost inevitable, given the way things were at that time.

There were only two of us left who were original founding members, and we were both ready to leave. We both had other jobs, so we left everything for the new members, which is as it should’ve been. But interestingly, from there on, no new posters were produced entirely by See Red. It became a very different workshop—they mainly did posters on commission. It was at a time when other ways of printing were coming in. We’re now good friends with two of the members who were part of that younger group, and we still do work together. Things were so heated at that time in many ways, but it was all good stuff.

Collectors Weekly: Do you have a favorite poster that the collective produced?

Stevenson: We’ve all got different favorites, but the one that’s been the most popular and most used has been “Protest,” the bright multi-colored one [see image at top]. That’s been used a lot. “Right On Jane,” was also very popular with schools and colleges.

“Right On Jane” from 1977 is a critical take on common children’s books, with the text and imagery in the first three frames copied directly from one of these books. © See Red Women’s Workshop.

Collectors Weekly: What did you do after leaving the workshop?

Stevenson: I was already working in a women’s prison teaching art. I was also teaching silkscreen printing and adult education, but I was doing three days a week in a women’s prison, and I left to do that full time. I later left the prison very publicly. I resigned on television because of the conditions for women who were on the psychiatric unit at that time. I then founded an organization which acted as a voice for women who were in long-term secure psychiatric prisons called WISH, Women in Secure Hospitals, and the organization is still going. We all went on into other careers pretty much, those of us who were there at the very beginning.

Collectors Weekly: How do you measure the success of See Red’s work?

Stevenson: I measure our success in as much as the posters were very popular, and they were popular with a wide range of women and all people. I don’t know how important they were in making change, but everything adds up to something. There was a lot going on at that time, and we were a part of that. It’s interesting that the posters are still very relevant for today—a lot of people still like them. We get an awful lot of requests to use the designs in books and publications, and requests to do talks or be part of exhibitions.

I think what comes across, particularly, is the energy in the designs. The posters have a freshness and a huge energy, and that very much reflects how things were at that time and how we felt about it all. We were very passionate about it, and that comes across in the work. To be able to put a poster on your wall that says something about a particular issue is important, and there is a shortage of that at the moment. There’s an awful lot online, but it’s all very fleeting—there isn’t much that has permanency, that people can put up on their walls.

Collectors Weekly: Do you see the work of See Red reflected in contemporary activism?

Stevenson: Not that I’m aware of. There’s more and more going on, and that’s fantastic, but things have changed. We were doing this stuff over 40 years ago. Images are exchanged very differently these days. All of us have moved on in one way or another and, yes, we’re still really interested in what’s going on. But I want to live now and in the future. I want to do art that reflects old age, work that reflects how we feel now as older people.

As you know, we’re all completely tied up with Brexit at the moment. It’s complete madness. Over a million people went to a march on Saturday. People feel very strongly about it, and honestly, if we do exit, I think half the country will go into national mourning. People feel very upset and anxious about Brexit.

Somebody was carrying one of our posters on the march. A friend sent a photograph of it, and it was the one that says, “Alone we are powerless. Together we are strong.” And I think that’s exactly how we will be—we’ll be a little tiny island. As part of the European Union, we had strength there. We felt much safer.

“Alone We Are Powerless Together We Are Strong” poster from 1976. © See Red Women’s Workshop.

(For more on the See Red poster collective, check out their book, See Red Women’s Workshop: Feminist Posters 1974-1990, or follow the group on Facebook)

Trailing Angela Davis, from FBI Flyers to 'Radical Chic' Art

Trailing Angela Davis, from FBI Flyers to 'Radical Chic' Art

War on Women, Waged in Postcards: Memes From the Suffragist Era

War on Women, Waged in Postcards: Memes From the Suffragist Era Trailing Angela Davis, from FBI Flyers to 'Radical Chic' Art

Trailing Angela Davis, from FBI Flyers to 'Radical Chic' Art Masher Menace: When American Women First Confronted Their Sexual Harassers

Masher Menace: When American Women First Confronted Their Sexual Harassers Political PostersFrom simple, 19th-century woodcut broadsides to modern color lithographs, p…

Political PostersFrom simple, 19th-century woodcut broadsides to modern color lithographs, p… Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Great Timely article. It’s unfortunate that their work is still so relevant today.