This article describes sterling silver items (such as punch bowls and tankards) popular in New York in the late 18th and 19th centuries, noting their strong Dutch influences and the evolution of the design styles. It originally appeared in the October 1947 Special Sunnyside Edition of American Collector magazine, a publication which ran from 1933-1948 and served antique collectors and dealers.

In 1800 when Washington Irving, son of a Scottish born New York merchant, made his first trip up the Hudson he found that fertile river valley a land teeming with twilight superstitions, old Dutch legends and lore. Ichabod Crane, Katrina Van Tassel, Brom Bones and other legendary characters had had their prototypes in colorful tales passed on by word of mouth through the river skipper, the innkeeper or the village crone.

Dutch-inspired teapot by Pieter van Dyck (1684-1750), a style popular in New York in the early 18th century and persisting until 1750.

To one as interested in antiquities and relics as Irving, the region must have presented a novelty. For here were snug stone cottages of Dutch farmers as well as imposing manor houses attesting to the solid character of their inhabitants.

Probably in no other section of the newly born Republic had manners and customs remained so fixed as in the rural New York community. For although colonial New York had been under Dutch rule for a scant forty years in the 17th century, descendants of the early settlers still were steeped in the legends of old Dutch life, kept up trade with Holland and spoke the Dutch tongue in church and market. Their possessions reflected their cultural inheritance and the silver they owned was no exception to the rule.

Punch bowl by Cornelius Kierstede (1674-1757), New York. Typical of the New York-Dutch style in the first decade of the 18th century.

Irving comments in his Legend of Sleepy Hollow on the corner-cupboard in the parlor of Mynheer Van Tassel with the door purposely left ajar to display the “immense treasures of old silver.” It is likely that such a collection contained at least one large two-handled punch bowl similar to that shown in fig. 1, for a bowl of punch had been the wager in the race between Brom Bones and the Headless Horseman.

Wedding tankard in the New York-Dutch manner, made in 1708 by Jan Niewkerk for Mr. and Mrs. Robert Benson.

The maker of the bowl here illustrated, Cornelius Kierstede (1674-1757), was registered in both New York City and Albany and was a favorite silversmith with New York-Dutch manorial families. Its eye-arresting decoration of floral ornament, inherent from the Hollander’s love of flowers, is Dutch in origin; yet no large bowl identical in form and decoration is known to the writer among the collections of 17th century silver in Holland. This particular form is not only typical of colonial New York but was a necessary possession in well-to-do families, whose amusements and bibulous activities, judging from contemporary descriptions, were worthy of the brush of a Teniers or Brouwer.

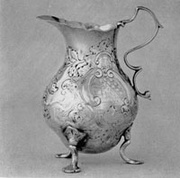

Rococo elegance of the decade prior to the American Revolution: a coffee pot made by the New York master craftsman, Myer Myers (1723-1795).

Even more popular than the punch bowl was the tankard, with its capacious drum and decorated cover in which New York silversmiths combined English form and Dutch decoration, one of the outstanding contributions in the pattern of American art.

Typical of its time is the tankard shown in fig. 2, made by Jan Niewkerk for Robert and Cornelia Benson on the occasion of their marriage in 1708. The broad drum and flat cover are based on the English tankard that was popular in the reign of Charles II. The foliated base band, engraved cover design, corkscrew thumbpiece and cast-handle ornament (to insure a steady grip), are Dutch in character as are the clasped hands, symbolic of the wedding, on the handle terminus. Since the Benson and Hoffman families were closely related by several intermarriages, it is not impossible that Irving may have seen this tankard when courting tragic Matilda Hoffman, who died not long after he became engaged to her.

Vice-President Aaron Burr's teaset made by Abraham du Bois prior to 1800, a Philadelphia interpretation of the classic style in American silver.

Sharing in popularity with vessels for strong liquids were those for tea which had come into style in the reign of Queen Anne. In New York as late as 1800, when Wall Street was the center of fashion and the Battery the favorite promenade, water from the tea-water pump was sold at a penny a gallon from door to door.

At the frolic held at Mynheer Van Tassel’s, Irving comments on “the motherly teapot,” such a one no doubt as that made by Pieter van Dyck in the first quarter of the 18th century, and thoroughly Dutch in character (fig. 3). The writer recalls seeing a similar pot, treasured in the South, which reputedly belonged to Katrina Van Tassel or her prototype.

Traveling inkstand made by Obadiah Rich, Boston, based on the classic tradition as modified in the first quarter of the 19th century.

The first noticeable break in this prolonged stylistic development occurred just prior to the American Revolution, when the elaborate multiple curves of the rococo invaded the ateliers of New York silversmiths, even those with Dutch patronymics. This change in style was the result of English importation and the fashion-conscious, newly rich merchant class of non-Dutch families, such as the Irvings who had settled in New York a decade prior to the American Revolution. Outstanding among the versatile craftsmen in precious metals of this era, and catering to the American Anglophiles, was the master craftsman, Myer Myers (172-1795).

Jewish by descent, Myers is known to have been patronized by James Stevenson, the merchant prince of Albany, and Philip S. Van Rensselaer, lord of Van Rensselaer Manor and Mayor of Albany, with commissions to make companion trays to imported English ones. His craftsmanship is ably illustrated by the coffeepot shown in fig. 4, a piece representative of the rococo style at its best.

Presentation urn made in 1825 by Fletcher and Gardiner of Philadelphia and given to Gov. DeWitt Clinton by New York City merchants.

The desire to create a new style suitable as a background for the newly formed Republic caused our silversmiths to discard the outmoded rococo style and adapt the classic urn shape. Indeed, the nation by 1800 was classic-conscious – from the trite comparisons between the Roman hero Cincinnatus and the late General Washington, to the new Roman architectural style fostered by Jefferson and expressed in the Federal buildings under construction in the newly established Capital. Thus was formed a classic pattern which in turn influenced the decorative arts.

In strong contrast to the exuberance of the rococo style was the formal reserve of the classic, with its straight structural lines of the classic urn based on excavated forms in stone, bronze and earthenware; for the great hoards of Roman silver familiar to us today were not found till later – the Bernay hoard in 1830; the Hildesheim, 1868.

Silver owned by Irving: One of a pair of plated Sheffield candlesticks, c. 18oo, in the spirit of the brothers Adam.

By 1800, Philadelphia, which had been the leading city in the colonies since the mid-18th century, the seat of the Continental Congress, and the capital of the Republic for a decade, produced the outstanding school of silversmiths in the classic style. The great refinement and distinction of this style is set forth in the teaset made by Abraham du Bois (fig. 5).

In such examples the solid grandeur of the classic shape, with decorative detail confined to ribbed and beaded moldings enriched by a marvelous surface finish, the last great period of American silversmithing is well represented This particular teaset was made for Jefferson’s vice-President, Aaron Burr, a patron of the arts and a man of fashion who, in the years before the fatal duel with Hamilton, lived in a large and luxurious house on Richmond Hill with liveried flunkies and a cellar of excellent wines. Irving acted as a reporter at his trial in Richmond in 1807.

The great drawback to the classic style was its lack of invention, due chiefly to the fact that it was based on an archaeological style. In the early years of the 19th century the craftsman’s ingenuity was taxed to provide variety and novelty. It was an age when travel for pleasure and education had become fashionable and the resulting correspondence voluminous.

Small traveling desks with tambour lids were cunningly contrived by the cabinetmakers, and in the same vein one finds the traveling combination inkstand and candlestick made by Obadiah Rich, of Boston (fig. 6), a cousin of the bibliographer and American consul in Spain who bore the same name, and in whose house in Madrid Irving lived while writing a part of his Life of Columbus.

When Irving left the United States in 1815 for his long sojourn abroad, it was the end of an era as far as the American silversmithing tradition was concerned. When he returned in 1832 the inventive capacity of the silversmith was being efficiently crushed as a result of the rise of the professional designer with no knowledge of the limitations of the silversmith’s art. This decline was furthered by photography, which was partly responsible for the direct imitation of forms and ornament of the past and perhaps worst of all, the combination of ornament of the past with current shapes.

Silver owned by Irving: Fiddleback serving spoon, by H. Cheavenes, c. 1815, and French pie server, c. 1838.

Illustrative of the early stages in our silver decline is the presentation urn of 1825 (fig. 7), the gift of the Pearl Street Merchants of New York City to Governor DeWitt Clinton for his public service in linking the great waterways of New York State with canals. The design was based on a stone or marble vase excavated among the ruins of the villa Hadrian but decorated: with bas reliefs of scenes of the Grand Canal along with romantic allegorical illustrations of the progress of art and science.

The few pieces of silver associated with Irving which have survived at Sunnyside serve as a mirror of his times, reflecting taste and travel (fig. 8). Of particular interest is the serving spoon bearing the unrecorded mark of H. Cheavenes and engraved with what purports to be the Irving crest. It is typical of the fiddleback pattern which, with its variations, was so popular in America from 1815 to 1850. Representative of imported English Sheffield plated ware are the candlesticks decorated in the Adam style. European travel was responsible for a set of ivory-handled French fruit knives and matching pie-server bearing the French assay mark for 1838 and initialed in old English letters W I stamped in blue, possibly the influence of Sir Walter Scott, Abbotsford and the Gothic revival. They were undoubtedly purchased on one of Irving’s trips to Paris while Minister to Spain in 1842-43.

The latest pieces in point of time are a pair of ornate Dutch vases and a small coffer of typically thin silver, chased in sentimental mood with a naked cupid driving a bumble bee harnessed to a fruit chariot. Can it be that Irving’s recollections of Dutch and New York Dutch silver owned in the Hudson River Valley are responsible for the vases and cotter or are they merely gifts from an admiring public?

It is to be hoped that some of the silver pieces which belonged to Washington Irving’s parents may find their way to Sunnyside along with early New York Dutch examples symbolic of the architectural moods of the house as well as of the characters created in his writings.

This article originally appeared in American Collector magazine, a publication which ran from 1933-1948 and served antique collectors and dealers.

Saving Vermont History, One Silver Spoon At a Time

Saving Vermont History, One Silver Spoon At a Time

Paul Revere, His Craftsmanship and Time

Paul Revere, His Craftsmanship and Time Saving Vermont History, One Silver Spoon At a Time

Saving Vermont History, One Silver Spoon At a Time Janine Skerry Shows Off the Silver Collection at Colonial Williamsburg

Janine Skerry Shows Off the Silver Collection at Colonial Williamsburg Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line

Mari Tepper: Laying it on the Line Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry

Nice Ice: Valerie Hammond on the Genteel Charm of Vintage Canadian Costume Jewelry How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture

How Jim Heimann Got Crazy for California Architecture Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of

Modernist Man: Jock Peters May Be the Most Influential Architect You've Never Heard Of Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick?

Meet Cute: Were Kokeshi Dolls the Models for Hello Kitty, Pokemon, and Be@rbrick? When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll

When the King of Comedy Posters Set His Surreal Sights on the World of Rock 'n' Roll How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos

How One Artist Makes New Art From Old Coloring Books and Found Photos Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures

Say Cheese! How Bad Photography Has Changed Our Definition of Good Pictures Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History

Middle Earthenware: One Family's Quest to Reclaim Its Place in British Pottery History Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Fancy Fowl: How an Evil Sea Captain and a Beloved Queen Made the World Crave KFC

Leave a Comment or Ask a Question

If you want to identify an item, try posting it in our Show & Tell gallery.